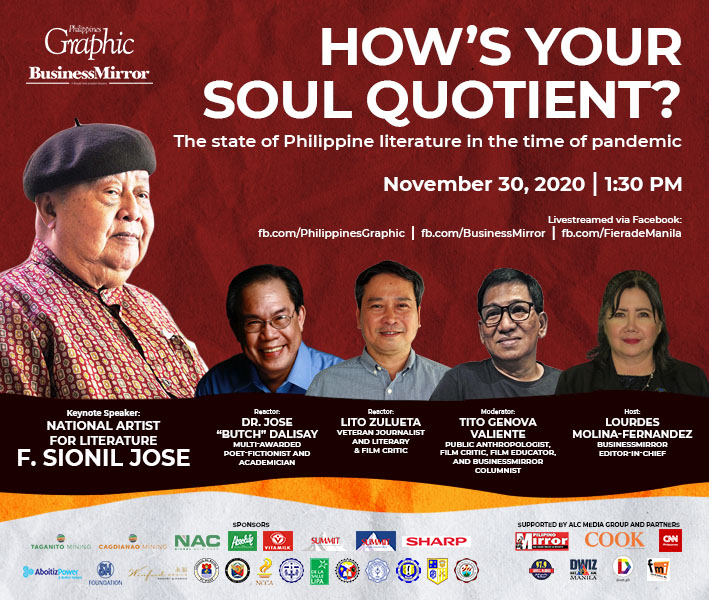

Delivered during the1st Philippines Graphic webinar on Literature—”How’s your Soul Quotient? The state of Philippine Literature in the time of pandemic,” November 30, 2020

In these past few months of lockdown caused by the pandemic, we are afforded time to remember and reflect. In our isolation and loneliness, we realize the ethereal brevity of life, and with this realization comes the helplessness, then the melancholy—that state of mind that is actually the bedrock of creativity evoking as it does our deepest pain, our loves, which are then articulated in words, in music, in spatial forms, in art. I hope we will see all this reflected in our literature, actualizing that old panegyric that bad times nurture good literature.

If we are profoundly concerned with our own society, our writing will also be a commentary on our society. This has been tradition almost for Filipino writers to do so, as exemplified by Rizal who towers above all Filipino writers.

Philippine literature in English is new and in a sense Western in form, a by-product of Spanish colonialism. When the Spaniards arrived, we did not have the classical literary traditions of Asia as developed by Buddhism and Hinduism, but we did have indigenous forms, the folk epics, the folk stories, most of which have survived today. In a sense, this presents a challenge to our writers—how to translate, remold, and recreate these archaic forms, and make them the solid foundation of our modern literature.

The Americans made English the language of instruction in the schools. It replaced Spanish as the language of culture, business, and government. It was accepted immediately, because it was an equalizer. Not so with Tagalog, which was decreed as the national language by President Quezon during the Commonwealth. It elicited a lot of opposition from the big ethnic groups like the Cebuanos and the Ilokanos.

Here, may I cite different examples of the adoption of a national language? Hindi, which is considered India’s national language, is not enforced on the Indians, who have large ethnic groups with developed languages and classical literatures.

In Indonesia, Javanese, the dominant language in that archipelago, was denied primary status and the Indonesians adopted instead a minority language of commerce, Bahasa. It was also accepted by the Indonesians for it made everybody equal. Today, Bahasa Indonesia is flourishing and has already developed a national literature. It has been modernized and is the language of instruction in the educational system. English is taught as a secondary language.

Our literatures in our own languages have not been ignored. Cebuano and Ilokano continue to flourish. In the meantime, the minor languages like Zambal, Pangasinan, Kapampangan, and the rest will continue, but will most probably die. We do not hear anymore of plays, of poetry in Pangasinan or Kapampangan. There are valiant efforts to keep these languages alive; their literatures must be translated into Tagalog and English so that they will have a much wider audience.

Our literature in English developed quickly after the end of the Philippine-American War in 1910. Philippine mastery of English has already produced quality prose and poetry influenced by the Americans in their earliest creative writing, the short stories of Edgar Allan Poe, the novels of Hawthorne. In grade school, we studied Longfellow’s epic poem, “Evangeline.” I can still recall the opening lines — “This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlock, bearded with moss and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight” — although at the time, I had never seen a forest of pine trees or hemlock.

We also memorized the classic Gettysburg address of Abraham Lincoln. It was later on that we studied the American classics like Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and the best from the “flowering of New England.”

Great American literature was primarily inspired by Ralph Waldo Emerson when he urged the writers of his generation to forego the romantic tradition they imbibed from England and celebrate America instead. Walt Whitman, Eugene O’Neil, Edith Wharton, then William Faulkner, Theodore Dreiser, then Hemingway defined American literature, gave it its sinews.

It was inevitable that America would influence Philippine culture and Philippine writing. After World War II, Filipino writer-teachers—the most outstanding of that period, NVM Gonzalez, the Tiempos of Silliman University and Ben Santos—went to the United States and imbibed the tenets of New Criticism which was then in vogue. They brought back these ideas together with writers workshops.

Today, long after the tenets of New Criticism had waned in the United States, many Filipino teachers are still mouthing them, using them, too, in the workshops that have proliferated. In principle, I don’t believe in workshops, they homogenize literature and cripple the imagination; there is too much emphasis on craft. There should be more input from history, politics, philosophy. But they provide extra income for writers, who all of us know, earn so little from their writing. I hope they will also bond writers, give them a higher purpose, the building of a nation.

Sometime in the 1950s, the American writer and writing teacher, Wallace Stegner, visited Manila and gave several lectures, one of which I attended. He, too, was a “New Critic” and he expounded on the fundamentals of creative writing, including “objective correlative” as first proclaimed by the poet, T.S. Eliot.

Stegner emphasized that writers should be contextual to be aware, involved, and rooted in their time and place. He wondered why there was very little social consciousness in our literature, why no one was writing about the peasant Huk rebellion which had not yet been concluded. I had just finished my novel, My Brother, My Executioner, the third novel in the Rosales Saga which dealt precisely with that conflict, but I was too modest to mention it, besides, at that time the proletarian literature of the Great Depression in America had already influenced the foremost Filipino writer of that period, Manuel Arguilla.

Contextuality is still very valid today, but so is innovation and modernization based on indigenous models. For instance, poetry in our languages transformed into rap, or the old style Balagtasan in modern form can be an interesting feature on television. The old comedia in Ilokano or moro-moro in Tagalog based on the Christian and Moro wars can be transformed in dramatic and poetic language to dramatize any of the ongoing conflicts in our society; it will then be more visually attractive and exciting with modern, stylized choreography. And our movies and TV dramas—the Koreans have shown how they can be tremendously improved if the best writers were harnessed to oversee their scripts.

With fewer venues for creative writing today, perhaps social media, particularly Facebook, can be the venue for poetry or the short “flash fiction,” which tallies with the short span of attention that is given to the printed word.

On another level, to encourage book publishing, the National Book Development Board should overhaul its program and stop altogether its annual contest. To promote publishing and at the same time cut down its bureaucracy, it can publish a bi-annual report on books published in the Philippines with a short review of each book for distribution to international libraries, particularly those with Southeast Asia collections, and to major booksellers all over the world.

Norway has a population of only five million. We are more than a hundred million now. Norway buys a thousand copies of each new book published in the country for distribution to libraries and schools. To do the same in the Philippines will assure all publishers that their printing cost will be absorbed by this purchase.

Let us now return to basics and definitions: what is art, literature, and the writer? The writer is a nation’s keeper of memory, without which there can be no nation. This demands honesty. If we are keepers of memory, we must be rooted deeply in our native soil, be the voice of our people.

Fifty years ago, at a writers meeting in Silliman, I gave a lecture on Art and Revolution. I echoed Albert Camus when he said, that every artist, in rejecting reality, is a revolutionary.

In her last novel, Gina Apostol concluded the Philippine revolution is a dream. All revolutions are dreams, but with faith and courage we can fulfill them. I have held on tenaciously to this dream. To this in my twilight and to my last breath listen, look at our history and recognize and accept we have a revolutionary tradition to fulfill, for us to banish the injustices that prevail and build a just and sovereign nation.

In conclusion, I hope that during this pandemic and the time it has afforded our writers, that they have used this time creatively. Sometime back, I wrote an advice to young writers. Permit me now to repeat the most important points I made in that article — the need to be true to one’s self, to be engaged with our self, our time, and our place and thereby assume an identity which commends us and to our people and the world as well, an identity that is truly unique yet universal as art always is. In other words, be Filipino.

PHILIPPINES GRAPHIC NOTE:

Viewers of the webinar are entitled to this Certificate of Participation. Message us your request in our Facebook page www.facebook.com/PhilippinesGraphic

Thank you.

Good evening Victor,

Thank you for writing to us. We appreciate your attending and we look forward to having you in our next webinar on Dec. 10 at 9 am. This is another very special web forum, one that deals with vaccines for COVID-19. Among our guests are the three international pharmaceutical companies directly involved in the development and production of a vaccine. I think this is the first time they will be talk on the matter.

We are just collating all the requests and will give you a blast email containing the certification. Expect it soon. Thank you very much and more power.

Btw, where is the photo you said you attached?