Jun was squatting over a burrow hollowed out by an old acacia’s jutting roots, wary of creepers that might crawl on him as he defecated. He was in a shitty mood. The dewy weeds tickled his extremities, and every now and then he was startled by unseen rustlings in the brush.

Ahead lay the vast fields of his family. He knew which was theirs from the parallel furrows that marked the earth, left there by the tractor which he could see far off thanks to the glint of sunlight reflected off its mirror. Over by the hut he could hear water slosh into a tin pail as it was being pumped from the well. He realized he had forgotten to bring water with which to wash himself. But for a twig nearby, there was nothing which he thought he could use to wipe his behind. Obviously, he couldn’t shout for water—he wouldn’t be able to bear the humiliation of the tenants being privy to his predicament. He cursed his bad luck.

Jun headed straight to the outhouse, which was really just a couple of rusty GI sheets hammered together, then bent and propped by rotting wood-posts. When he came out, Niña, the tenant couple’s six-year-old daughter, was staring at him with accusing eyes.

“Halla! Did you hoorah before you poo-pooed by the acacia?”

Jun brushed past her without a word. The girl, unfazed at being ignored, tugged at his shirt.

“The lady will be angry! You have to offer atang!”

“Don’t bother Sir Jun, silly child,” the girl’s father, Felit, said.

Felit was Jun’s pa’s stocky foreman. He had farmer written all over him. He was short and swarthy, with thick veins that snaked all over his strapping body, and had wiry hair that was washed blond from the application of agua oxigenada in his youth and constant sun exposure. The sheen of his body, which was visible even in the shade, reminded Jun of the old mahogany furniture back home, their patina discernible despite the heavily-curtained and vault-like living room.

“You shouldn’t be feeding the child’s mind with such ideas, Manong Felit,” Jun said. “She’ll be a laughing stock if she spouts such nonsense in the big school.”

“Ah, but there’s no harm in stories, is there, Sir Jun?” Felit said.

He was chewing a tobacco leaf, which lent him a ruminating air. The image of a carabao dispensing aphorisms while chomping cud popped up in Jun’s mind.

“There are stories, and there are stories,” Jun replied. He was about to expound on his point, on how some stories, when believed without question, had led to the commission of the greatest crimes in humanity. However, Manang Tansing, Felit’s wife, called everyone over to the table for breakfast.

The table was made of a layer of bamboo slats rafted together with rattan twine, then placed over staves that were driven into the ground. On it was a large, soot-blackened cauldron of steaming rice. Another pot was filled with mung bean soup with eggplants and various green leaves picked from Manang Tansing’s vegetable plot. In a battered, concave pan, links of longganisa that Jun brought along from his parents’ house swam in their rendered annatto-colored fat. The foreman’s wife was slicing tomatoes, which she tossed into a tin bowl containing fermented anchovy fry and smashed chilies. As the farmers swarmed towards the table, she dropped the tomatoes and waved her knife to fend them off.

“Let Sir Jun have his share first! Here, Sir, sorry there’s no chair so you can eat at the table,” she said, flustered as she handed him a chipped, blue-rimmed, enamel plate and mismatched utensils.

“It’s okay, Manang, they’ve been working since before dawn. And there’s no need for these—,” Jun said as he plonked the spoon and fork on the table then waved to the farmers, “go on!”

“Niña! Niña! Now where did that child run off to again?” Nina’s mother asked. “Felit! Where’s your daughter?”

“There she is! Niña!” one of the farmers said. He was pointing at the distance, then disappeared as he trotted off to somewhere behind the hut.

The farmer returned with Niña in tow. Bits of leaves and grass stuck to the girl’s knobby knees.

“I offered the atang for you,” the girl said to Jun, all solemn.

Jun was taking Niña back to the city with him. He had no illusions about it, but he hoped that Niña could somehow fill the unnerving silence that had taken over their home when Ava, his daughter, had died three months ago. His wife, Ana, was inconsolable, and had retreated to somewhere within herself that he couldn’t penetrate. It’s always difficult to lose a child, Jun knew. Nevertheless, he couldn’t help feel that Ana was being selfish with this radical inward-looking, self-negating grief. Edmund—Ava’s twin—was still alive, after all, and needed his mother.

Ignored by his mother, the help had reported that Edmund had taken to talking to himself as he played by the grove of trees at their backyard. Auntie Mameng, oldest among them, said a girl of Ava’s age could help. In the absence of a doctor’s prescription or professional advice—Ana’s withdrawal from the world meant that she couldn’t be moved to see a specialist no matter how her husband pleaded—Jun thought that maybe it was worth a shot.

“I’ll talk to Felit,” Auntie Mameng said. This early, the signs pointed that Felit’s child had a good head on her shoulders, and the chance to get to study in the city shouldn’t be passed up, she said. Else she might run wild, which, though a better prospect than going nowhere in their town that lay outside modernity, was still a waste.

So here he was, back in the place that had figured largely in his childhood. Back after more than a decade of tethering himself to the grind and high stakes of litigation in the metropolis to avoid being sucked into the wheeling and dealing world of politics that his pa had insisted was his by birthright.

He had decided to stay a week. Enough time to get the necessary papers in order himself. He didn’t like using his pa’s gofers. Even in mundane matters as this Jun wanted to be on top of things. He could do with the fresh air, too. Lately, to avoid the oppressive emptiness at home, he had taken to busying himself with work, camping at the office whenever he wasn’t needed out of town, eking every possible second to delay the inevitable moment when he had to head home to scale —always futile—the defenses Ana had built around herself. Though she was physically there, yet Jun was convinced his wife had been entombed along with their daughter.

He was at his wits’ end. The week before he left, desperate to elicit a reaction from her, he had hit her. It was unintentional, his hand seeming to have taken on a will of its own as it landed on her face. As a purple bruise bloomed on her cheek, blood trickled from her lip, like an afterthought, parenthesized by the strands of hair that hung limp on each side of her head. Still, a blank.

So Niña had to succeed. Jun nursed a seedling of fear that were Niña still to fail, he would down tools and just walk away. The fear shamed him. After all, he loved his family. He loved Ana with the same intensity as that day one spring in Sevilla, with the air redolent with the fragrance of the blossoming orange trees, when the swish of her hair as she turned to look back at him as he tarried behind with the elder law professors stopped him in his tracks and the certainty of love had punched him in the gut so hard that he was left gasping for air. He had tried to bury the fear deep within the recesses of his soul; a mistake, as sentiment only grows in the damp, fertile ground where lie a man’s secrets.

Jun had expected that the endless fields would liberate him. But here he found he was dead wrong. One could feel cramped in open spaces, Jun had failed to remember. Back home his wife’s stolid resistance was bounded by the walls of their house. Here, the absence of walls meant that the oppression was limitless—it followed him whichever way he went.

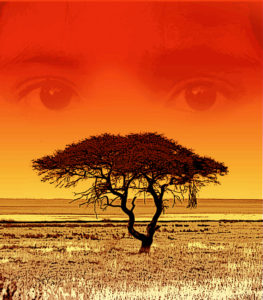

It was present in the trees, ancient, yet still, sure to outlive them all. Present in the faces of the farmers—poverty threaded through every sinew of their body. Present in their words, incapable of shedding their servile state, laced with old wives’ and farmers’ tales and superstition so that one had difficulty threshing out truth from fiction, and unbelieving in the modern ideas that Jun was convinced could lift them out of their rutted existence. Present in the roads, unpaved but for the track that led to his family’s farm. Present in the present of a backward town that was mired in the past and unapologetic about its miserable condition. The worst of it was that Jun knew his family was largely responsible for the town’s decades-long state of misery.

The day had passed as days always pass in this town —the slog of the hours at once imperceptible and evident —a stretch of time where the shadows are constant in their shortness, betraying no hint of time’s progress, the scalding sun alternating with a burning wind, providing no succor; then, abruptly, the lengthening of silhouettes, the dimming of the sky, the apotheosis of the heat that had settled on the surface as the damp and biting breath of dusk descends on this hell on earth. Observing all of this it is easy to understand why the myths continue to thrive here, Jun thought. Sitting on a tree stump, he had busied himself with blowing smoke rings to while away the time before Manang Tansing’s call to supper.

Overhead the sun was losing its battle with the creeping darkness. A hiss, then the smell of gas. Without seeing it Jun knew the allampran had been lit. The word, though unuttered, rolled on his tongue. Unbidden, the image of an Andalusian fortress sprang from his memories. A kiss, flavored by Jerez, under the impassive stare of the turret. Laughter, crystalline, ringing with joy, in defiance of the onslaught of night. Jun thought about etymologies, the likelihood of things an ocean apart linked by a single root able to transcend the limits imposed by water on land, by time on distance, time on time itself —present on past, past on present —different in form but indivisible in essence, the essence of which was to stand against the march of an opposing force.

A commotion broke Jun’s reverie. With the help of the lamp’s shimmering light he detected dark figures hunched in a circle over something that lay on the ground. He could hear the worry in the snatches of murmurs that were carried by the breeze. Curious, Jun walked over to the congregation.

“What’s wrong?”

No one answered. Instead, the circle broke open to reveal Felit, his feet splayed on the dirt, cradling his daughter on his lap, a Pieta with roles reversed. Niña was mumbling, her pupils darting from side to side. At the edge of his vision he spied Manang Tansing rushing over, her cry of alarm registering late. Jun stooped to feel Niña’s forehead. She was burning with fever.

“She’s delirious,” he said.

“The lady,” Felit said.

In the darkness Jun could see Felit’s face drained of blood. Manang Tansing knelt by them. She crossed herself once, twice, thrice. She was rocking as she lifted her face to the heavens, imploring with incoherent sobs.

“We need Na Saling,” Felit said. His voice was shaking, but Jun could discern steel in it, as if he would brook no argument.

“Take her inside,” Jun said. “She needs a doctor.”

A pullet, white against the inky night, squawking in terror, aware of its imminent death. A knife slitting through fragile neck bones and throat, distinctly audible from the creaking matins of nocturnal creatures. The musk of coconut oil, a counterpoint to the perfume of the dewed forest. The rasp of aged vocal cords, ululating in the language of his childhood, foreign because forgotten. A vigil. The hope of others that the fever passes. His despair at this obstinacy, this distrust of science, the disdain for the foreign, which they heard has caused harm to hundreds.

The febrile state is extended. Two days now. No one talks, everyone going about their duties as soundlessly as possible. The girl is marked by angry dots of blood, by the hairline, on the neck. Black mud-water streams from her lower orifice, unrelenting. Panic spreads, should the ritual be repeated? They try to hide it, but Jun feels pinpricks of blame shooting from their glances. Again, she needs a doctor. He is not heeded. A first.

The week is past, and Jun must return. He returns empty-handed. The beam of his car’s headlights lance through the gloaming. The street lamps, the ones that work, have not yet been lighted. It’s a long drive home. Half a day, easy. He had come to fetch a lamp to dispel the gloom that had encroached on his home. His failure was a rock tied to a rope which end was noosed around his neck. The car sped straight on. To Jun it felt like hurtling down a yawning hole. G