Stories of children caught in the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic

Governments respond to the COVID-19 pandemic by enforcing lockdowns and community quarantines to contain the virus and protect public health. But the impact of these measures on children become, more often than not, underreported collateral damage.

Merlina, 26, a mother of three, worries about her children Anna and Elmer (not their real names). Aged five and six, they still could not talk. She tries her best to engage them in conversation but the siblings would merely smile, frown, or giggle.

Breastfeeding her youngest, Merlina is without means or opportunity to feed her young family. She used to sell rugs at the public market in Tanay, Rizal. But the pandemic and the resulting community quarantine made selling impossible. Her husband has suffered the same fate, losing his job as a construction worker in Laguna because of the lockdown.

Merlina and 24 other informal settler families used to be shanty dwellers in Pasay City. Until they were relocated to Tanay town in Rizal province, about an hour and a half ride away from Pasay City. Without access to electricity or water, their crowded shelters made them vulnerable to COVID-19 and other diseases.

According to Merlina and her husband, the local government would send water trucks to their relocation site, but dwellers need to pay P5 for a pail of water. Drinking water costs P30 per gallon. As for electricity, a solar powered LED bulb provides light during the night.

“If we want to charge our mobile phones, we need to go to the guard house of the resettlement site, the only place that has electricity, and the area where we can watch the news from television,” said Merlina.

Between paying for water and the load for their cellphones, Merlina said, they are more concerned with earning money so their children can have food. She worries about the speech delay of Anna and Elmer.

“They haven’t started going to school yet. And although I am very much concerned about their being unable to talk, I have not been able to bring them to the doctor to know more about their condition,” she said.

GLOBAL STUDY

The COVID-19 pandemic has so far affected 99% or 2.3 billion vulnerable children living in 186 countries, including the Philippines, that implemented some form of restrictions like community quarantine and school closures, according to Save the Children’s 2020 global report, “Protect a Generation: The impact of COVID-19 on children’s lives.”

The report is a result of an international survey conducted among children and caregivers since the outbreak of the pandemic, taking in over 25,000 respondents (including 8,000 children) across 37 countries.

“It is clear that the most deprived and marginalized children are being hit the hardest by the pandemic, exacerbating existing inequalities and pushing the most vulnerable children even further behind,” said Inger Ashing, Chief Executive Officer of Save the Children International.

Ashing has been with Save the Children for more than 25 years. She has worked to reduce segregation and social inequality, with a special focus on improving the situation in socio-economically disadvantaged areas.

The Save the Children 2020 global report on children also found that for families who relied on low pay or unstable work, disruption in income directly related to missing meals and limited access to nutritious food for their children.

Children may not be severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic but they are becoming its biggest socio-economic victims, the report said.

In September, Save the Children launched a more detailed global research series “The Hidden Impact of COVID-19 on children,” which revealed the lifelong and devastating impact of the pandemic to children’s health, nutrition, education, learning, protection, wellbeing, family finances and poverty.

The study was implemented in 46 countries, including the Philippines. It resulted in the largest and most comprehensive survey of children and families during the COVID-19 crisis to date. Some 17,565 parents and caregivers, and 8,069 children were participants in the survey.

Part of the global research series: The Hidden Impact of COVID-19 on Child Poverty showed that at least 77% of households lost their income during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a higher proportion (82%) of those considered poor lost their income due to COVID-19, compared to those who were not poor.

Nearly 96% of parents and caregivers who participated in the research reported that they struggled to pay for their children’s essential needs, particularly food, as well as health care, house rental and utility bills.

SCHOOL CLOSURES

For the first time in human history, an estimated 1.6 billion learners globally had their education disrupted due to lockdown and quarantine measures enforced to stop the spread of COVID-19.

School closures did not only impact children’s learning but also their health and nutrition needs. It posed potential risks from physical and humiliating punishment, sexual and gender-based violence, child marriage, child labor, child trafficking, as well as recruitment and use in armed conflict.

A report submitted by Save the Children to the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education in the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights emphasized that “the longer schools are closed, the less likely they are to return to school once they reopen—and those who do return are at greater risk of dropping out.”

Schools do not only provide children with a space to learn, but also a safe place where they can receive meals, access healthcare, including mental health services, and play with their friends.

Teachers also act as responders and protectors of children who face various forms of abuse and violence at home and in the communities. “But with school closures, children are missing out on these essentials the school environment can offer,” said the submission report.

Save the Children’s global report “Protect a Generation,” revealed that more than eight in 10 children surveyed felt that they were learning little or nothing at all during school closures.

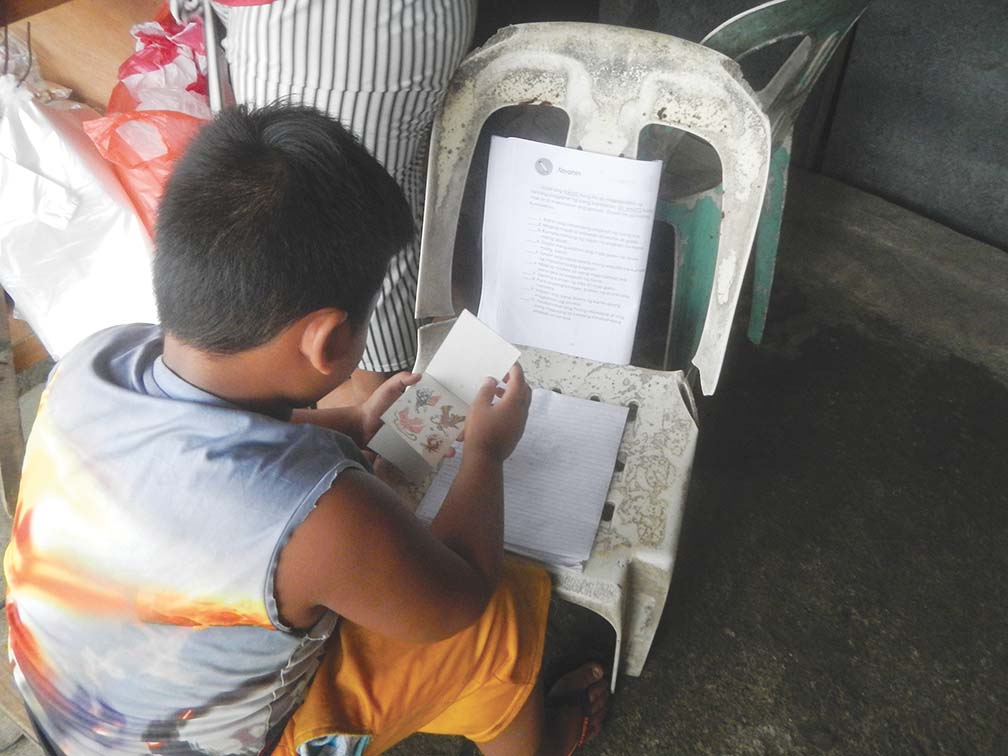

The number is higher for children living in poor households, displaced children, and girls. Fewer than 1% of children from poor households said they have access to the internet for distance learning, despite more than 60% of national distance learning initiatives rely on online platforms.

At least 40% of children from poor households said that they need help with their schoolwork, but they have no one to help them.

The survey also showed that two thirds of parents and caregivers reported that their child had received no contact from teachers since their school closed.

CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES

The COVID-19 pandemic has also hindered access to effective learning for children with disabilities. The study revealed a higher proportion of children with disabilities (71%) who need access to home schooling and learning materials, compared to children without disabilities (51%).

Children with disabilities (60%) also reported “not having someone to help them” in learning. A higher proportion of children with disabilities (86%) reported an increase in negative feelings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Due to limited movement during quarantine, children with disabilities faced risks of experiencing abuse and violence at home. The study said at least 43% of child respondents with disabilities reported violence at home, compared to 15% of child respondents without disabilities.

Vivien is mother to Reden, 11 who was diagnosed with speech delay. She works as a house helper while her husband is a construction worker. Reden is left under the care of his sister Rose Ann, 12, when their parents are away for work.

The family lost their home in Catanduanes when Super Typhoon Rolly hit Bicol and they had to stay in an evacuation center. Reden’s father made a shack from salvaged materials from their destroyed house.

Vivien admitted that it breaks her heart seeing her children sleeping through cold nights in their shack because her family cannot afford a sturdier house which is safe from disasters.

Rose Ann dreams of a better life for her family. “When I become a nurse, I would buy a house for my parents and provide for Reden.”

SAFE SCHOOL REOPENING

Malacanang approved on December 14 a proposal of the Department of Education (DepEd) to conduct pilot implementation or dry run of face-to-face classes in select schools within areas with low COVID-risk for the whole month of January 2021.

But on Dec. 26, Pres. Rodrigo Duterte recalled the order because of the emergence of a new COVID-19 variant in the United Kingdom that threatens to enter the Philippines.

Duterte added that he could not take the risk since not much is known about the new variant, except that it spreads faster.

Since classes resumed on October 5 last year, learners attended online classes or used printed modules by way of TV and radio platforms to prevent the spread of COVID-19 among learners.

Save the Children called on governments to work with health experts in the safe reopening of schools to protect children, their families and communities, with investment in water and sanitation and hygiene facilities.

It added that distance learning programs created or expanded during school closures should be maintained and scaled up to help children who cannot return to school and to continue to use these programs in the event of further school closures.

As mentioned in its global report: Support for children’s mental health and psychosocial needs must be addressed by qualified school personnel and teachers. The safe return to school should also involve catch-up or remedial education, and blended learning approaces whenever children can only intermittently attend school.

EXTREME WEATHER

In the Philippines, children living in the Bicol region faced the compounding impact of COVID-19 and the onslaught of extreme weather events like Super Typhoon Rolly and Typhoon Ulysees.

Save the Children Philippines deployed a humanitarian response team to Albay, Camarines Sur and Catanduanes to provide life-saving support to affected children and their families.

More than two million people in the Bicol region, with children numbering 450,000, were affected by Super Typhoon Rolly, according to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC).

In Catanduanes, 12-year-old Barn witnessed how flash flood washed away their house when Super Typhoon Rolly hit their town.

“I felt sad seeing the house I grew up in, lose its walls, roof and all of our belongings,” said Barn.

She and her family tried to pack all essential belongings, including the needs of her one-year-old sister before the typhoon. But flood started to rise, forcing them to seek shelter in houses located on higher ground. “We had to swim through waist-deep floodwaters. I was scared that we might drown or get hit by debris,” recounted Barn.

When her family reached a neighbor’s house, Barn helplessly watched as floodwaters and violent winds washed away their house.

The 12-year-old hopes that people could have access to timely and accurate information on weather events so they can better prepare and avoid its devastating impact. “I am studying hard to reach my dream of becoming an architect someday to design typhoon-proof houses. I hope to be successful and to be able to provide for my family so we will no longer need to evacuate and seek shelter at our neighbor’s house.”

VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN

The incidence of violence against children, mostly by parents and caregivers, has dramatically increased globally during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The more household income that has been lost owing to COVID-19, the higher the reporting of violence in the home by both children and parents or caregivers,” the global report bared.

At least one in six children reported violence at home during the pandemic. This is mostly in the form of physical and verbal abuse. Also, one in five parents and caregivers similarly reported violence at home. The study was based on a survey of 31,683 parents and caregivers, and 13,477 children aged between 11-17 years old in 46 countries including the Philippines.

Violence in the home setting is strongly linked with loss of household income.

For children whose families did not lose their source of income due to COVID-19, only 5% of them reported violence at home. Conversely, for children whose families lost their household income source, 19% of them reported violence and risk of violence in their homes.

Mental health and psycho-social well-being of parents and caregivers are significant in reducing violence against children.

At least 26% of children whose parents and caregivers lack access to parenting support—including counseling, mental health services, domestic violence services, cash transfers, childcare and parenting advice and support—reported violence in the home setting, compared to only 12% whose parents and caregivers have access to counselling, and parenting support.

“Spending more time with parents and family, and having a stronger relationship within the family were also the primary themes highlighted by children when asked what they had enjoyed the most about this time [during the COVID-19 pandemic],” the research said.

POSITIVE DISCIPLINE

To help parents and caregivers support children’s learning at home during the pandemic, Save the Children and the Department of Education conducted a series of webinars on positive discipline.

The webinar, held from September to October last year, provided a guide to parents and guardians in supervising their children’s learning under the online and modular set-up through a series of courses promoting positive discipline.

Positive discipline is an approach that helps build stronger relationships between parents/guardians and children. It consists of steps such as identifying long-term goals that will focus on the characteristics, values, and the kind of relationship that parents would want their children to have when they reach adulthood.

The webinar also provided parents and guardians with tips in managing stress since it is one of the factors that affect parents’ disciplining practices.

Positive discipline have tools such as Warmth and Structure. Warmth is creating a loving and safe environment where children feel and learn trust, security, and respectful communication. Structure is scaffolding children’s learning by providing them with information and guidance they need to perform what is expected of them, to learn from their mistakes, and solve problems.

RURAL, URBAN ABUSE

The study also shows that children living in shanties or poorly ventilated homes in urban areas are more at risk of neglect, as caregivers may not be able to stay home and provide care for children. Likewise, these children also face high risk of abuse as the increased stress and anxiety of caregivers might cause them to lash out at children.

Children living in urban areas are twice likely to be living in overcrowded conditions, compared to those in rural settings. Parents/caregivers in urban locations reported a higher rate of violence in the home (23%) compared to rural respondents (17%).

The study showed that the impact of COVID-19 has been more challenging for children living in urban settings. The mental health of child respondents in urban contexts was consistently worse than that of peers in the countryside.

Children living in urban areas were more likely to feel less happy (75%), hopeful (55%), and safe (64%) than before the pandemic, than children in rural areas (55%, 43%, 48% respectively).

Almost two in three children in urban households had no access to safe outdoor spaces (63%), compared to the overwhelming majority of children in rural areas (79%).

The highest cases of COVID-19 infection (90%) reported in urban areas have been at the centre of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 90% of the reported cases.

“How the world responds to COVID-19 has the potential to change the cities of tomorrow. In the rupture caused by this crisis, is an opportunity to address deeply rooted urban inequalities, reassess the food security of our communities, their access to basic services, to healthcare and their rights to access land and housing,” the report stated.

Save the Children said governments should see an opportunity to build back better, more inclusive, equitable, safer and resilient urban systems.

Children’s feelings about COVID-19 has undeniably affected children’s well-being. Almost three in four child respondents (74%) reported feeling more worried than before the outbreak, almost two in three (62%) report being less happy.

The prolonged community quarantine and school closure increased negative feelings of both parents and children.

Children worry over lack of food and are concerned that their loved ones may get infected by the COVID-19 virus, according to a children’s consultation conducted by Building Urban Children’s Resilience Against Shocks and Threats of Resettlement (BURST) Project of Save the Children.

The group used online platforms, SMS and phone calls with children aged 11-17 from informal communities in Pasay City and relocation sites in Naic, Cavite.

Children also said most people in their neighborhood complain about their situation, particularly issues about “where to get food, how to survive, and the uncertainty of not knowing when the enhanced quarantine will end.”

Children also feel disconnected with their friends due to school closure and limited mobility.

While at home, some children have to bear with extreme heat but cannot take a bath and maintain personal hygiene due to lack of water, the report added.

Distressed by circulating rumors and fake news, and the lack of information in their communities, the children are asking local officials to provide them accessible and child-friendly accurate information on what COVID-19 is, why the quarantine is being done, how the government is addressing the COVID-19 pandemic and how they can protect themselves and other children in their communities.

Relief goods being given to their families are not enough, according to the children, stressing they also need medicines and vegetables. Children also urged local leaders to provide them educational and leisure materials so they can continue learning and be productive during the quarantine.

CHILDREN’S RIGHTS

The Philippines marked its 30 years of ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of a Child (UNCRC), which mandates governments to respect and fulfill the rights of children to health and survival, participation, development, protection from abuse and exploitation.

Save the Children’s global study revealed that the lockdown and community quarantine, while unavoidable, violate fundamental rights of children that are critical to their health, safety, development and well-being.

Children living in poor households reported less well-being than children in non-poor households. These children from poor households reported eating food less (39%), and spending more time doing chores (50%) and taking care of siblings (55%).

School closures have resulted in violations of the right to education for children and could impact their development.

There was need to enact legislative and administrative measures to meet the particular needs of children experiencing the most deprivation and marginalization.

Governments including the Philippines which ratified the convention are required to adopt the UNCRC articles into national legislation, and facilitate children’s participation so they are heard and their views taken into account by the state and their caregivers.

Laws and policies should give children the right to remedy or to complain, even within households—when decisions affect them, such as curfews and other limitations by parents.

The survey found that less than half of the children felt that they were listened to. However, a lesser percentage of children or one in three children reported that they were asked their opinions, and just one in five children were involved in making decisions together with adults in their house. The study found that most children were worried about how the COVID-19 virus and response impacted them and their families, and that their ability to participate in society was curtailed by lockdowns or quarantine measures.

Children in poor households had slightly fewer opportunities to be heard while children in urban areas, have more opportunities to be heard. The survey also shows that 10% of the child respondents in urban areas reported, “adults in my household do not talk to me at all about COVID-19.”

COVID-19 threatens children’s rights to survival and development, and to the highest attainable standard of health.

The study shows that one-third of the children reported eating less food than before (35%), while more than half of the households reported they had no sanitizer/soap and access to water (20%).

Children’s well-being is compromised during the pandemic. Almost three quarters (74%) of the children reported feeling more worried than before the pandemic, felt less happy, bored (60%) and more sad (59%) than before the pandemic.

The limited mobility during the quarantine, and school closure deprive children (51%) to socialize with peers and teachers.

Children also expressed concerns that their families (65%) need money or vouchers for food and essential items.

CHILDREN IN CONFLICT WITH THE LAW

The pandemic-induced community quarantine intensified and increased the degree of uncertainty and the painful waiting for the resolution of cases of children in conflict with the law.

Carlo was charged with drug-related cases and had been staying in Bahay Pag-asa (temporary shelter) for the past eight months. He just celebrated his 18th birthday in the temporary shelter in December last year.

The 18-year-old was one among hundreds of children charged with drug-related offenses who surrendered to local authorities in the face of the government’s anti-illegal drugs campaign.

“I felt sad when I learned about the 122 children deaths in the anti-illegal drugs campaign because these children were not given a chance to live, be with their loved ones and were robbed of their future,” Carlo said.

The COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine restrictions resulted in delays in court hearings and even release of children in the temporary shelter. Carlo is worried that the hearings for his case were delayed for four months, and only resumed in May last year.

“Spiritual development and playing basketball are my favorite activities in the temporary shelter. It helped me to understand myself and motivated me not to revert in wrongful doings,” Carlo said.

Carlo shared painful stories of abuse in the hands of authorities until one police officer showed kindness and provided him food when he was in jail. “He (police officer) inspired me to dream of becoming a good policeman someday.”

While in Bahay Pag-asa, Carlo attends online class under the Alternative Learning System. “Through education, I can have a better future and be able to help my family once I get a job,” he said.

Prior to the community quarantine, Carlo’s family visited him every day. He assured them that he is being taken cared for by the shelter’s house parent.

Save the Children Philippines implements Protecting Children in the Anti-Illegal Drugs Campaign (ProAct), a project that seeks to build stronger child protection systems, protect children from the adverse impacts of the anti-illegal drugs campaign, and promote nonviolence and respect for human rights at the national and local level.

ProAct provided computer tablets to Carlo and other children in Bahay Pag asa so they can use for their online court hearings, online classes, and even extra-curricular activities like dance exercises or games.

Children and youth who were found violating curfew guidelines during the Luzon-wide quarantine suffered from cruel, and degrading treatment from authorities who arrested them.

In Pampanga, a 15-year-old boy was arrested along with three LGBTIQ+ individuals for violating curfew guidelines. The minor was made to witness a lewd dance and kissing of the LGBTQI+ individuals as punishment.

Four boys and four girls were also arrested in Binondo, Manila in March 19 last year for violating curfew. Local officials forcibly cut the hair of seven of the children while the one who resisted was stripped naked and ordered to walk home.

Local officials also placed five young people inside a dog cage in March 20 last year in Sta. Cruz town in Laguna Province for violating curfew rules. In Cavite, two children were also locked in a coffin last March 26 as punishment for violating curfew rules.

Save the Children Philippines has called on authorities to adhere to the Joint Memorandum Circular 2020-001 issued by the Department of Interior and Local Government and the Council for the Welfare of Children that clearly defined the procedure in handling children who are caught violating the ECQ guidelines.

The circular mandates that no penalty shall be imposed on children who are caught violating the ECQ, instead they should be brought to their residence or the barangay official at the nearest barangay hall to be released to the custody of their parents.

DILG GUIDELINES

The Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) issued new guidelines in June last year ordering barangay leaders and law enforcement officers to treat children who violated curfew regulations under the community quarantine humanely and with dignity.

This comes after the numerous call outs of Save the Children Philippines for the government to address the issue of rising cases of violence against children during the enhanced community quarantine (ECQ).

The guidelines will apply to children in street situations, those in conflict with the law, and children at risk or those abandoned and vulnerable to physical, sexual, and economic exploitation. The new rules, issued on June 23, were based on the provisions of the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act or Republic Act 9344, as amended by RA 10630.

Law enforcement officers should also avoid the display and use of firearms, weapons, or handcuffs on minors, unless absolutely necessary and only after all other methods have been exhausted.

The additional guidelines will be integrated in the Joint Memorandum Circular of DILG and Council for the Welfare of Children (CWC) dated April 6, on the protocol on reaching out to children in street situations, in need of special protection, children at risk, and children in conflict with the law.

Atty. Alberto Muyot, Chief Executive Officer of Save the Children Philippines, said the COVID-19 pandemic is already taking a toll on children’s lives as they missed out on classes, and their mobility was curtailed thus, preventing them to go out of homes and interact with others, causing them psychosocial distress.

He said the pandemic also continues to worsen hunger and malnutrition among children belonging to low income families and whose parents or guardians have lost income or livelihood due to the quarantine. This has forced minors to leave home to help look for food and earn an income for their families.

“Children who allegedly violated curfew rules, or those in street situations must not be placed behind bars or under harsh and inhumane conditions without consideration of their rights,” said Muyot.

“Instead, barangay leaders and law enforcement officers should protect these children by turning them over to their parents, guardians, or social welfare office,” he added.

The new DILG rules also direct authorities to endorse the child to the Barangay Council for the Protection of Children (BCPC) or to the Barangay Violence against Women and Children (VAWC) desk officer.

A 15-year-old girl in Cabugao, Ilocos Sur was killed after filing a molestation complaint against two police officers from the neighboring town of San Juan.

Investigations show that the young victim and her 18-year-old female cousin, who attended a party and reportedly got drunk, were apprehended by two cops for alleged violation of curfew. The victim managed to escape after being abused by one of the cops. Her cousin was allegedly raped by the other.

After lodging a complaint about the incident at the Cabugao Police Station, the victim was shot repeatedly by two motorcycle-riding men on her way home.

Save the Children Philippines denounced the killing of the adolescent girl seeking help from the police. Ironically, the murder coincided with 30th year of the country’s ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.