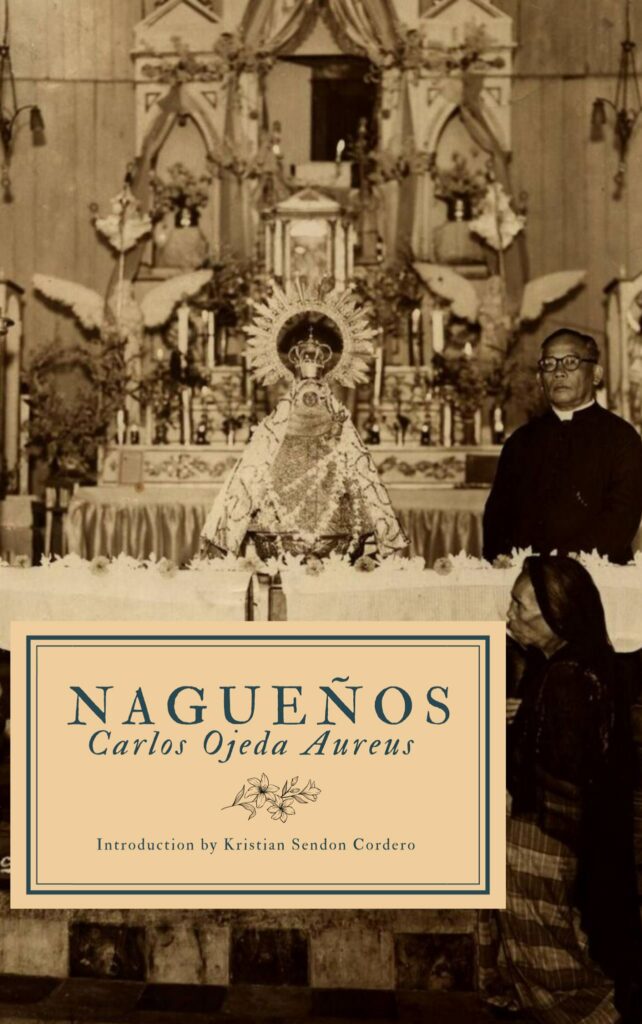

In an essay, Carlos Ojeda Aureus describes the Catholic imagination as sacramental, baroque and always, in saecula saecolurum, a comic narrative that leans towards hope.

The lost pearl and the lost sheep will have to find its way back to its owners and in the case of the lost son, a grand return to his caring father awaits us where he is greeted with a feast that punctuates this favorite parable.

There is always this sense of restoration, as proclaimed by its creed: the communion of the elect, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the eternity of life.

This grand vision of renewal in a world that is charged by grandeur of God (to quote the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins) is what drives the characters in Aureus’s Nagueños towards an epiphany, making them real, their stories, visceral. The plot revolves around this circle of completion.

POWER OF THE TANGIBLE

In Nagueños, Aureus highlights the power of the tangible, albeit corruptible like the human body and the physical world. Nonetheless since the world has already been sanctified through this incarnation, therefore, it follows that these sacramental manifestations like the holy water or the sacred oil are spiritual presences.

In Aureus, the world has been re-sanctified and all things are now made new. Hence, the made-in-China-minted medallion or the century old image of Our Lady sculpted and animated with dog’s blood, or the formulaic prayer to Saint Michael whether in Bikol or in Latin or the small crucifix raised by Mr. Caceres against Bhoy, the leader of a notorious fraternity gang who tried to abduct and rape Cynthia Dy are efficacious manifestations of this Catholic imagination.

This power is best represented in the dramatic encounter between the old bachelor and this young hoodlum in the story Sanctuary which happened at the main entrance of Naga cathedral.

The incident however is an obvious restaging of the curious incident that happened in Rome in 450 AD. The Romans upon learning about the possible conquest by the invading barbarians immediately went into a penitential procession led by an aging Pope, Leo I.

At the gate of the city, the Vicar of Christ met the ambitious Attila who has threatened to destroy the city built by Caesars. According to the Catholic version of the story, the pagan Hun, after seeing the cross, raised by the supreme pontiff with the presence of the supplicating populace, decided to retreat and never to bother Rome again.

Some alleged that heavenly armies had appeared to the non-believers while another view claimed that Attila left because he saw nothing in Rome but a dying civilization represented by a decrepit leader. The event however is considered as a miracle story of the cross and is as memorable as the first story about Constantine’s vision of in hoc signo vincis (By this sign you shall conquer) which marks his conversion and the beginning of the Roman brand of Christianity.

OLD ORDER

Aureus, who openly supports the pre-Conciliar Church, has manifested this deep affection for the old Order of the Mass in his first book.

In his ideal world, Latin reigns, it’s the supreme lingua franca, and the venerated images are made of wooden or ivory materials and never of stained glasses or plaster of Paris.

But as a cardinal rule, things go and change and Aureus would have to see the changing of the guards as the old world passed away. And so by way of his stories, he remembers and laments how suddenly one day the wind of secularization has entered his beloved and seemingly formidable church. This change has reduced the highly ornate liturgy into a pompous meeting very similar to a civic gathering.

As a storyteller, however, Aureus does not pontificate nor is he proselytizing. Needless to say, what attracted me to these stories is how Aureus poeticizes the struggles of his characters having to live in relentless doubt, despair, and death.

In “Flakes of Fire, Bodies of Light,” the culmination of the physical state of the body now being cremated reveals the glorious mystery of this collision and combustion. But instead of pointing us to the terrible fires of hell, we, like Tanya, see something as she peeps in the observation vent. In this particular moment, Tanya realizes how the dead body of her husband Sid is resurrected into the lesson of the mathematical truth of the Fenyman’s diagram. Indeed, a beautiful site of how matter is transformed into a sacramental that reminded her of the pages of her Physics textbook.

Read the story, “Typhoon,” and encounter the fragile humanity in Padre Itos, a clergyman who contemplates leaving the priesthood and yet, towards the end, decides to stay in the church after receiving a tangible sign: a handkerchief which was found in the image of Our Lady of Peñafrancia and was given back to him because it has his name on it.

Read, too, the story, “The Night Train Does Not Stop Here Anymore,” and discover how Naty Angeles, an OFW mother confronted the death of her only son in a hazing incident, a vicarious simulation of the Christ’s via crucis. The story begins with an angry mother destroying all these religious articles, the material evidences of her unwavering faith to the God who promised security and comfort, and yet tragedy happened. On her way back to Naga carrying the remains of her only son, the deep sense of the sacred is revealed to Naty Angeles as she is approached and assisted by another mother-and-child character in the person of Gaia, a person with HIV.

In the case of the male protagonists in the story “Wings,” and “Reunions,” and “The Late Comer,” it is the Chinita woman who initiates, intuits, and allows Mr. Caceres to confront his phobias be it of flying, or sex, or the stage, or of homecomings and class reunions.

Padre Itos’ decision to remain a priest despite his continuing struggles within the institutional church, and Naty Angeles literally entering the illumined church of San Francisco while the bell toll marks the beginning of a new liturgical season are clear indicators of Aureus’ Catholic imagination— and clearly, there is always this light at the end of the tunnel.

ENDURING FICTION

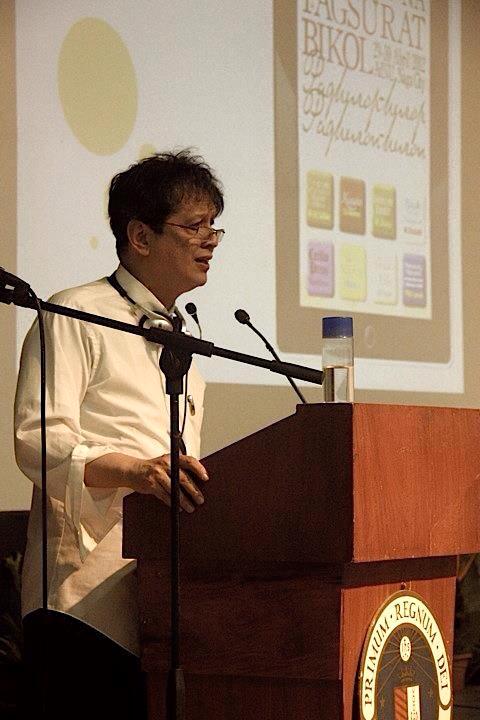

Having lived most of my early adult years in Naga City since the year 2000, the same year I got to hold my first copy of the Aureus’ book, I have witnessed how Naga, the site of all his stories has emerged from a ‘parochial’ city into what it is now— aside from being the heart of Bikol, it is now dubiously called, the center of local governance.

Over the years, we have seen the rise of new malls and the 24-hour convenience stores, massage parlors, fancy cafes, student dormitories and gated subdivision communities, including the one that is called Urban.

A mosque has been built one stone’s throw away from the parish church in Concepcion, and near the Basilica of Our Lady of Peñafrancia is an Indian Sikh temple. A Porta Mariae, a mere replica of France’s Arc de Triomphe now serves as the main entrance of the badly repainted cathedral.

The old Naga Restaurant along Gen. Luna Street is gone and is replaced by another Jolibee, and in front of it is a McDonald’s. The supermarket which claimed to be the first and largest concrete supermarket in Southeast Asia is now baptized as The People’s Mall. An ill-maintained coliseum now bears the name of a former mayor who is also honored with a museum designed like a giant mound, which also serves as a stockroom/a favorite venue for pre-nuptial shoots/another parking area/tambayan.

I now ask: What stories shall we draw from these new sites in Naga as we continue to experience and endure the pandemic that has put us all in a standstill? We now live on-line as our cities and towns are re-classified according to quarantine types. People and the Nuestra Senora de Penafrancia, to whom Aureus dedicated his book, send us more storytellers who will re-imagine our lives into necessary and enduring fiction.