In a country that has 110 million inhabitants and approximately 149 languages, we live and breathe in a multilingual atmosphere. This includes English, the language we inherited from American colonial education.

However, despite aggressive efforts since the beginning of the 20th century on the part of our colonizers to educate native populations in English, the average Filipino continues to associate English and Spanish with the colonial elites, creating what scholar Vicente Rafael calls “a linguistic hierarchy roughly corresponding to a social hierarchy.”

In my school days, those who dared to speak the local languages were either extorted (hilariously and painfully made to pay 25 centavos for every local word we uttered), punished, or both. Filipino or what many still call Tagalog, was promoted as an alternate state sponsored national language. Still, many consider the vernacular languages, among which Filipino is included, to be inferior, ineffectual, and impudent.

Within the last ten years, however, it seems there has been a shift in the thinking about the importance of the local languages.

WRITING, FILMS

Many young writers from the regions now write in their local languages. Writing workshops have been established to support these greenhorn talents who consciously made the effort to first write in the local languages.

Others, who began their careers writing in English or Filipino, like Luis Cabalquinto, now either translate their old works into Bikol or are writing new works in Bikol from the start.

Films, including these short videos uploaded in the social media conveniently use the local languages in their production. Most recently, we have seen the rise of regional films in Kapampangan, in Waray, in Ilokano, in Pangasinense, in Hiligaynon and I am sure that the next time we check Netflix, we shall have more films coming from these linguistic communities.

To amuse myself, I regularly subscribe to Pinangat ni Pando, where the old ‘action’ films of Fernando Poe Jr., and even the legendary basketball player Kobe Bryant are dubbed in Bikol, talking

about which one has the best pinangat (a favorite local dish) or who sells the best baduya (banana fritters) in the town Daraga. The same can be said with Reina King, a transgender blogger from Iriga City where she discusses and comments on the problem of the local electric company by dubbing the Kardashians.

DIFFICULTIES

In the context of our ever-shifting government policy, the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE), was passed into a law as Republic Act 10253.

Regrettably, however, despite the program’s good intentions, such top-down policies only reinforce existing hierarchies and privileges in public education, rather than achieving any real change in the mentalities of the people.

Having facilitated many workshops on this topic, I have often been approached by teachers and parents to discuss the difficulties they face when teaching in their mother tongues.

This is largely because of a lack of good pedagogical materials but also because of their unfamiliarity with the languages. They resort to English or Filipino as a matter of convenience.

In my opinion, inequality between languages can be mitigated by interrogating our existing multilingual reality against the backdrop of the pernicious legacy of colonialism.

INTEGRATING TRANSLATION

To this end, we must integrate translation as a key component in our pedagogical praxis, and develop an approach to language and literature that views them not as closed, petrified specimens of cultures and ethnic groups, but rather as works-in-transit.

In other words, literature and language should transcend their origins, and expand the range of local languages and literatures—like my mother tongues, Bikol and Rinconanda. Yes, it is possible to have two or three mother tongues.

Therefore, when I translated foreign writers Jorge Luis Borges, Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke and Karel Čapek into Bikol and Filipino, I was well aware and conscious that I was waging a countermovement against prevailing policies and mindsets that privilege English over our local languages.

AWAKENING

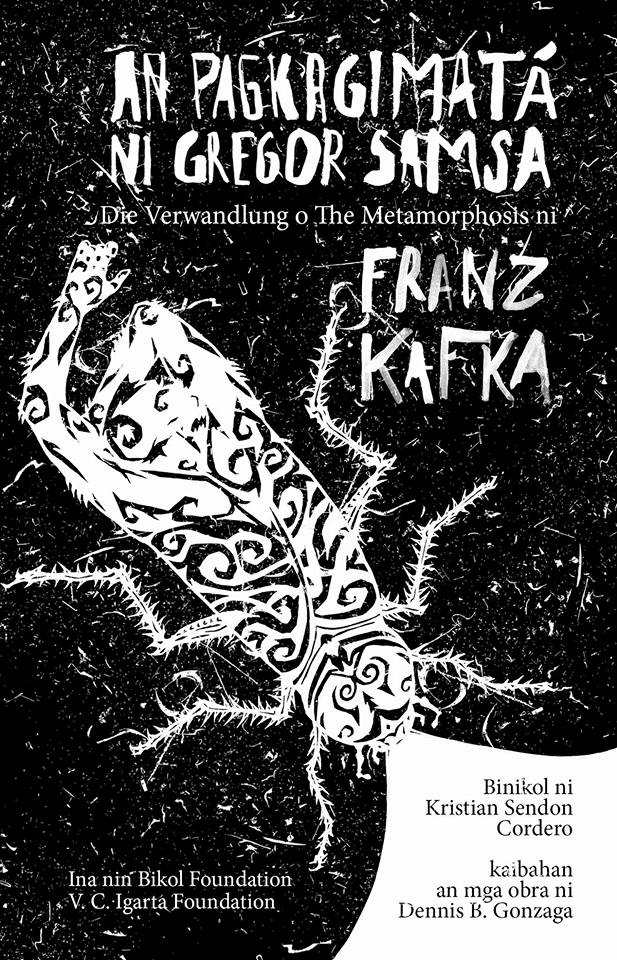

Metaphorically, I prefer to think of translation as an awakening. When translating Kafka into Bikol, I deliberately changed the title “The Metamorphosis” to “An Pagkagimata ni Gregor Samsa.”

For me, the word pagkagimata has a spiritual or a revolutionary undertone similar to the word awakening.

I translated Gregor Samsa’s dialogue into Rinconada (from the Spanish word, rincon, ‘at the corner’), precisely when his speech was most incomprehensible to his family.

In contrast to Bikol, the local media, the academy, and the Catholic Church prefer not to use Rinconada. The latter remains a highly oral language. But with this translation, both Bikol and Rinconada can experience a kind of metamorphosis—in part because this is the first time both languages are being used together in the same text.

I view this work not as a self-contained literary or linguistic artifact, but rather as a work-in-transit, which, despite limitations, has started opening new doorways for Bikol and Rinconada. Therefore, to write and translate in our local languages is to be in a constant state of awakening. And yes, I don’t have a problem when a cockroach speaks and dreams and laments in the language very, very similar to my mother’s tongue.