San Francisco, back in the day, was everyone’s favorite city, ‘the city that knows how,’ cosmopolitan city by the bay, where one grew up with musicians and artists and writers walking its steep and windy streets in almost every neighborhood. This is a story of two artists, one very famous and the other quite obscure.

Charles Mingus, the legendary jazz bassist and composer came in from the San Francisco autumn mist for a game of pool because he had a couple of hours to kill before his performance at the Keystone Korner near Chinatown and Manilatown. Big droplets of slanted rain shone in cars’ headlights as the vehicles maneuvered the arduous and glistening streets on this particular night during the era of the sixties merging and forging into the seventies. On Kearny Street, the Mabuhay Restaurant was one of the favorite hangouts of the Filipinos. It was owned by the Masonic Brotherhood of the Dimasalang, one of the largest and most influential Filipino organizations at the time, and it is said that writers like Carlos Bulosan, P.C. Morrante, Stanley Garibay, and many others hung out there during their stay in San Francisco when they wrote pieces for the local Filipino papers and journals.

The Mabuhay had a mid-size counter and several tables for eating. In the back, where happens the real action, as in this case, behind a flimsy faded curtain that split in half, were three pool tables, a big brass spittoon on the floor, hat racks and coat racks, benches that lined the walls, tin-can ashtrays spaced evenly over another counter, and a light bulb above each table. In the pool hall, smoke from cigar and cigarettes floated lazily upwards becoming distinct shapes where the shafts of light pierced the room.

That game of pool was Mr. Mingus’ undoing. Mingus wanted to wait out the hard part of the rain before his gig (he had a couple of hours) when he saw the sign “Mabuhay Restaurant, Food and Pool.” It would be a perfect combination for his wait in the rain before his gig up the street at The Keystone Korner. But as it turned out, like most seemingly perfect beginnings, it was a disaster. For at the pool hall of the Mabuhay Restaurant, he had the misfortune of playing Yaw-yaw, the Pinoy hustler from Mindanao. Charles Mingus was a large black man compared to Yaw-yaw, a slightly-smaller-than-medium-size Filipino.

Charles Mingus put his big instrument down beside the door as he checked out the place, seeming to take a liking to it right away. He flicked off beads of raindrops from his long, black cashmere coat and hung it on the rack sticking out of a cement wall.

“Hi. How you all doin’?” he smiled. After a while, he said, “The sign outside said food and pool. I see only food tables. Where are the pool tables?”

“They’re right behind that curtain, in the back,” Manong Al, an old timer who was not that old and who himself dabbled with the jazz piano, volunteered a reply. “Were you gonna eat first? You know Filipino food?”

“I love that stuff,” he said. “Can’t get enough of it.” He lifted his scarf off his neck and hung that with his coat. “But I never eat before I play,” he said opening his hand, palms up, like a preacher blessing his congregation.

Manong Al meanwhile seemed to be in a state of restrained euphoria. He did not know what to do with himself, as if holding his pee in some discomfort, or in delight.

“Anyone for a game of eight ball? Nine ball? Rotation? Whatever.” Charles Mingus ambled toward the curtain and parted it, ducking his head in, the footsteps of his big smile still on his face. It was a friendly smile.

Manong Al meanwhile sidled over to answer the stranger, “Why sure. What you wanna play?” And he followed Mingus inside the curtains.

“Well, whatever you want.”

“No, no. Not me. I retired. I just bullshit now. Maybe you play Yaw ober der. Hey, Yaw-yaw. C’mon ober here. Play some pool with this gentleman.”

This back room was a little darker, and the light was not as uniform as it was in the restaurant. Their brightest spots were, of course, the lightbulbs directly over the pool tables.

“Yeah. Just tryin’ to kill some time before my gig up the hill,” he said, his voice deep sounding like his bass instrument.

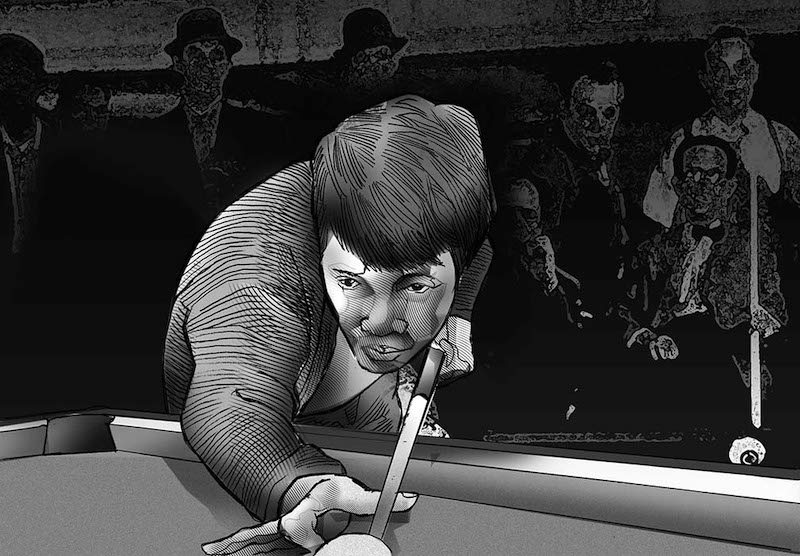

From the smoke-filled room emerged a brown Asian figure, pool stick in hand, tapping the floor with the handle end and chalking the tip, cocksure and five foot five. “Sure ting,” said Yaw-yaw. He had on a crumpled, floppy brimmed hat.

“Howdy, friend,” said Mingus and extended his hand. The other looked Mingus up and down.

Manong Al turned to Mingus, and gesturing towards the newcomer, “This is Yaw-yaw.” The old timer then looked at Yaw-yaw “This is Charlie Mingus,” and added, whispering with some restraint in Yaw-yaw’s ear, “you dumb, ignorant shit.”

Yaw-yaw looked Chinese in Chinatown and looked Japanese in Japantown and looked Pinoy in Manilatown. Because of this he frequented these neighborhoods’ pool halls with ease and felt at home there, including George’s Pool hall on Buchanan street in Japantown where every game was only a dime and one can buy just up the street, a good Chinese meal for seventy-five cents from Soo Chow’s Restaurant which was owned by Koreans.

But Yaw-yaw is Pinoy. He got his name for pretty obvious reasons: he talks a lot when he plays. Yaw-yaw ng yaw-yaw.

“What’s your pleasure?” asked the big man.

“Let’s do some eight ball.”

“Sounds good to me.”

Charles Mingus was a large, not only in status, as in the field of jazz, but also in plain physical stature. He looked almost massive to a Filipino like Yaw-Yaw. And his huge case for his string bass did not diminish his stature. Yaw-yaw said, “I break.” And they played.

It did not take long for Mingus to start losing, and losing big. In fact, he lost more than he could pay. The more he lost, it seemed, the more he got into the game. Yaw-yaw always trapped Mingus into dropping all his own balls too quickly in the game of eight ball. Yaw yaw would still have a lot of his own balls left before having a shot at the eight ball, but those same balls served as obstacles to Mingus’ path of shooting. Those balls would always “hook” Mingus so that he would have no clear shot whatsoever. Then he would have a lot of Yaw-yaw’s balls to block his shots every time. And when Yaw-yaw would see an opportune moment, he would shoot straight and true. He would run two or three or four balls at a time, talking and yaw-yawing all the while, and then, at the end, take the game. Mingus could not resist shooting his balls into pockets every time he had the opportunity. He did not know that patience was a virtue especially in pool. He did not plan ahead like Yaw-yaw did. Now he was paying for it. Well, not really, as it seemed to be turning out. The question of paying became the problem.

The big black man’s head was turning every which way and saying something about him being short of the money he had just lost to Yaw-yaw. “Well, like I said, I don’t think I can cover ALL of it, but I got to go to my gig now or I’ll be late, see. But I’m coming right back to cover the rest, okay, brother? I mean I’ll be just up the street. That’s where I’ll get the rest of the dough, see.”

Yaw-yaw, small as he was, lunged at Mingus. The big man seemed to have almost laughed in astonishment. But Yaw-yaw was not going after the big man, and that laugh provided the gap of distraction for Yaw-yaw to snatch the big cased instrument of Mingus, almost ripping it from the latter’s loose grip as he held the case on top by his left hand. As Mingus’ head snapped left and right for some explanation, from someone, anyone, Yaw-yaw quickly swept the instrument away, like a newly-wed bride, to the toilet. Everyone heard the lock click from the inside. “You give me my goddam money, I give you your instrument.” He shouted from inside the toilet.

“I got a gig in half an hour, Joe.”

“Das your problem. Your word is as good as cash you said. And my name ain’t Joe, Joe.”

“Name’s Charles. My name ain’t Joe, either. I’ll get the cash for you. Right after the gig. C’mon man. I’m only short 25 dollars. I’ll give you the 25 plus another 25 after the gig. Come to the show. Bring whoever you like. I’ll give it to you right there.”

“He doesn’t know you, Mr. Mingus,” said Manong Al turning to the musician, trying to explain. “I mean, of you.”

Yaw-yaw true to his name shouted from the toilet: “I know him. He gambles without any money! He’s gotta pay before he plays”

“He had the money Yaw-yaw. It ran out. Just like everything else.”

“Yeah? Why did he keep playing, then?”

“Because he’s a stupid gambler like you. I seen you do it lots of times.”

For a while there was dead silence. “Do I have to pay?” came the voice weakly from inside the toilet.

“Pay for what?” Asked Manong Al.

“For the show up the street.”

“Of course not. I’ll take you in myself,” Mingus interrupted.

“Nah, you don’ need to do that,” came Yaw-yaw’s quick reply, his tone slightly softening. “I’ll be there, though. I wanna hear you play dat ting. Al says you’re good. He’s the one who knows music. Hear him play the piano. It’ll make you cry.” Though not loud, Yaw-yaw’s voice rang clear in that toilet acoustic. He opened the toilet door just a wee bit, ever so slowly, and asked, “You really want to go, huh, Manong?”

“Yeah, he’s good, Yaw-yaw.”

“I hope he’s not good like the way he shoots pool.”

“He’s good, believe me. Angels will be singing to you, Youngblood. And you’ll remember your first kiss, man.” Manong Al said.

“First kiss? First kiss my fist!” Yaw-yaw snaked his way out of the toilet and appeared tightly hugging the instrument and added: “you sure he’s good? I play, too, you know.”

“I know. I know you play, Youngblood. I heard you pluck that guitar.”

“Come with me, then.”

“You bet I will.”

The two Pinoys turned to Mingus. “Take it.” said Yaw-yaw. “Go on. I’ll just go up the street to the International Hotel and clean up a bit, then we’ll be at the joint.”

“I’ll be waiting. My word is cash.”

“You said that before. We’ll see,” said Yaw-yaw

“Do you guys do ‘Prelude to a Kiss’?” asked Manong Al. “I like dat.”

“You just show up, baby. We’ll do it for you.”

Yaw-yaw handed Mingus his enormous instrument case until the big man got complete hold of it. “Here,” said Yaw-yaw curtly. Mingus grabbed the case and quickly turned to go. Without smiling or saying a word, he lumbered up Kearny street, then Columbus Avenue, then he was gone.

Beside the famous Hungry-I nightclub, across the street in his room at the International Hotel, as he was quickly getting ready, Yaw-yaw thought of his own guitar playing days as a youth among the vast plantation fields of Dole in Mindanao. Yaw-yaw was a guitar player himself who had a makeshift band in his hometown in the Visayas. It was a rag-tag type of band with a one-string bass grounded on an upside-down washbasin, a wash board for some fancy percussion, a guitar and/or a ukulele, and for vocals, whoever was drinking and/or handy at the time. He played guitar with a lot of spontaneity (the way he played pool) all his life so he could be considered a jazzman, only his text was Filipino music with some contemporary mainstream U.S.A. music around the Second World War era. But this Charles Mingus fellow he had never heard of before. He put on a fresh dip of his Three Flowers Brilliantine pomade then put on his floppy-brimmed hat. He was ready to step out.

He met Manong Al waiting at the lobby, and started walking towards the Keystone Korner. Manong Al, unlike most of the manongs here in Manilatown, was born and raised in the City. Never been to the Philippines. Manong Al was 10 years senior to Yaw-yaw, but they always talked like peers. Just as they were passing the police station about a block away from the joint, Yaw-yaw asked.

“Are you sure about this Mingus cat, Manong?”

“He’s the real McCoy, Youngblood. Aint you heard of Charles Mingus, man? That’s him,” said Manong Al.

“Mingus my ass,” said Yaw-yaw. “He owes me money and he’s gotta pay.”

“I told you he’s the fucking legendary jazz musician, you idiot.”

“Mingus cunnilingus my ass,” Yaw-yaw said.

“What kind of a musician are you? You don’t even know the masters of your trade.”

“The kind who can play pool.”

When they turned the corner, they saw a line at the ticket booth hidden under the awning, folks smoking and making small talk, their collars turned up against the wind and misty rain. The gig was about to start but there was some commotion at the bar inside. Yaw-yaw spotted Charles Mingus through a crowd of people and he in turn saw Yaw-yaw. Mingus waved and smiled and immediately talked to someone near him, gesturing towards Yaw-yaw near the ticket booth. Before Yaw-yaw and Manong Al got to their turn on the line at the ticket booth, someone from the joint came up to them and whispered something in their ears whisking them away to a choice seat, front and center.

Then the show began. Mingus, when the music started, seemed to have forgotten about Yaw-yaw altogether. He never looked at him once. First, the notes started hovering around Yaw-yaw’s sentimental rememberings. He recognized some of the tunes but it was the notes themselves and their sounds that took Yaw-yaw away. Each note rang crystal clear and the tone that came out of the trumpet player resonated in his brain even when he was not playing anymore. The musicians played independent of, yet essential to, each other. Like smoke from the pool hall lazily drifting into the night, the saxophone came in as subtle as the rain. He was not familiar with any of the players, but Yaw-yaw loved the sounds they orchestrated. The saxophone’s silky maneuverings took him away, past remembering, and behind it all persisted the pulse of Mingus’s bass. Somewhere, somehow he heard the rondallas of his hometown in the Philippines. Then they played “Prelude to a Kiss” for Manong Al and they called and mentioned his name and told the audience that he too played some and if he would like to dabble with the piano and play along with them.

“Hell yah, das my paborit.” Al said and he jumped up on stage leveraged by his arm. He played and they all played along with him and Yaw-yaw was carried away into the well-deep days of his childhood in the Visayas and his wandering days in Mindanao.

After the show, Mingus came up to Yaw-yaw and paid off the twenty-five plus another twenty five—fifty bucks. “Here,” said Mingus. “I got the man to give me the night’s pay in advance.” This time it was Yaw-yaw who did not look at Mingus. Or the money. He just quickly took it and walked up to the tip jar by the edge of the raised stage area and said to Al, “Godammit,” and dropped twenty-five dollars in the jar. “You’re right. He’s good.” Then he turned and walked away without saying anything to Mingus.

Walking back to Manilatown in the steady rain that night, Yaw-yaw told Manong Al, “I didn’t know music could be played like that.”

“This, I think, I have been telling you for years.”

“Take you from sad to glad in just seconds. And for real, too! Real sad and real joy, you know. I saw the notes hovering like in the rondallas before when I was young in the Philippines, you know. You tell that Mingus, Manong Al, that next time he comes to town, drop by and get a good ol’ fashioned Filipino meal from the Mabuhay Restaurant. My treat. I robbed him of his dinner tonight.”

That’s Yaw-yaw. Still talking.