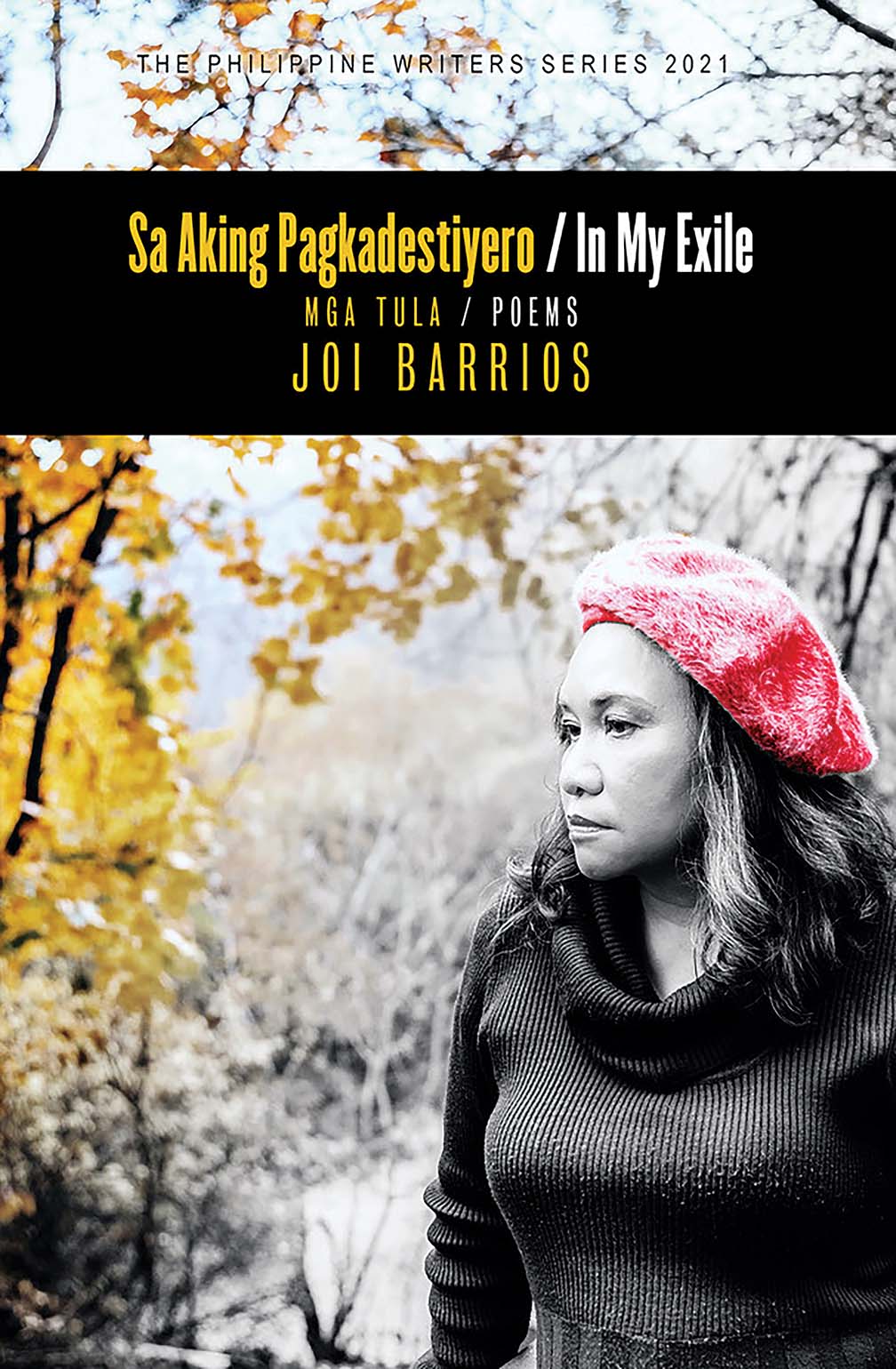

Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2021 (with translations in English by various writers)

Sa Aking Pagkadestiyero/In My Exile by Joi Barrios rings a bell to the reader who is familiar with the daily news, the injustices, the struggle for freedom and equality. The angst of the author, who has been in exile in the United States for years, surfaces whenever she remembers the distance between her motherland and the fact that exile is also her choice because she finds personal happiness in her American husband Pierre, a professor and a psychiatrist who is supportive of Joi.

Whatever the situation the poet is in, the poems are clear testaments of her stand in life. In her introduction, she unapologetically shoots a powerful poem.

Sa Aking Pagkadestiyero

Ipinagluluksa ko ang sandali

ng aking pagpili

sa pangingibang-bayan.

Pero saang puntod luluha

at magtitirik ng kandila?

Wala, wala.

………..

Nagpapatuloy ang himagsikan

sa aking kaloob-looban,

kasama nila sa aking bayan sa silangan.

Sa pinakamadilim na sandali,

naaalala ko ito.

At ako’y nabubuong muli,

may armas na nakasukbit,

Lagi’t lagi,

handang-handa sa pagbabalik.

In My Exile

I grieve the moment of my decision

of leaving.

But find no graveyards for weeping

No candles to light.

Nothing.

……….

The revolution goes on

within me,

and with them in my country

in the east.

In the darkest of days,

I remember this,

and I am whole,

and battle-armed.

Ready for home.

Always. Always.

And so, the poet goes out on a limb, criticizing some policies of the Philippine government; former President Rodrigo Duterte’s sexist and misogynist remarks; the murder of a Filipino gay by an American enlisted man, who was allowed to leave the country with impunity; etc.

“Sagot ng Puke/ The Cunt Strikes Back” alludes to Duterte’s order to the soldiers to shoot the women of the New People’s Army (NPA) in the vagina. “Ang Kuwento ng Inidoro/The Toilet Story” depicts how a dirty toilet bowl witnesses the gruesome moment an American soldier kills Jennifer Laude. “Sa Bingit ng Panganib/Dangerous Work” shows the dangers to health and life of workers in factories, in constructions, in the mines, above ground, underground, and in the sea. Even nuns in Mindanao could not hand a letter to the Pope because the nuns were accused of being members of a militant organization. The poem, “For Security Reasons: Liham sa Santo Papa/For Security Reasons: A Letter to the Holy Pope,” is a strong reaction to the detention of the said delegation of nuns.

Also included in this poetry collection is a poem for Maita Gomez “Rosas/Roses”; “Sa Harap ng Tangke/Tanks,” which recalls the EDSA People Power, and other noteworthy and unforgettable musings. Joi Barrios further pays tribute to other friends and comrades like Behn Cervantes, parents who have lost a child, persons who have died young; her brave companions in street theater of yesteryears, her lament while in exile and during the pandemic.

Joi Barrios, however, not only writes about anger and grief but also about love and hope, not only about war but also of peace.

She ends her fourth book of poetry with “Sa Pagdiriwang ng Pagsinta (Para kina Alnie at Lisa).”

Hindi ko na kailangan

ng tulang kumakapit sa hinagpis,

at may patak ng luha sa papel.

…….

‘Pagkat naririyan ka,

katuwang, kabiyak,

kasama sa pakikibaka

……

Ang sabi nga ni Balagtas:

Kapilas na langit

Sa aking dibdib.

This last poem, of which there is no translation, speaks of unwavering love and trust.