Our front door opened right into the sidewalk, and the street sloped down to a lily dappled river, in our house in the city. Across the river a soap opera was always taking place: A man with two wives lived in an unpainted house beside the lumber mill. When the sun went down the wives began to quarrel, clouting each other with wooden clogs, and a bundle of clean wash came flying out of the window into the silt below. We watched them chase each other down the stairs, clawing each other’s clothes off and rolling down the embankment, and the dogs of the neighborhood surrounded them, barking, snarling—till from the lumber mill the husband emerged—a shirtless apparition with a lumber saw in his hand.

At least once a month they held a wake on the river bank. They rented a corpse, strung up colored lights and gambled till the wee hours of the morning. Sometimes a policeman wandered in having heard some rumor, and poked around with his night stick. But there would be the corpse, and it was truly dead, there would be the card games, but no suspicion of betting (the chips having been scooped away together with the basket of money) and the policeman would saunter away, wiping a tear, leaving the poor relatives to their grief and their gambling.

We must move to another neighborhood, my father said everyday. We planted trees to screen them from sight, we planted trees to preserve our respectability. A truck unloaded two acacia trees on our doorstep, saplings no bigger than I. The houseboy made a bamboo fence around their trunks and every afternoon the maids hauled out pails to water them.

Soon the trees grew tall and lush with yellow-green leaves and the crickets sang in them. Then the street boys shook them down for bugs and crickets, or stripped off the bark with pen knives or swung on the branches till they snapped. My father waged an indefatigable battle with the street boys for why should they want to destroy beautiful things? He was terribly good with a slingshot and seldom missed his target for ammunition he used a round day pellet instead of a stone and made a painful red mark. In time my father just had to lean out the window and the boys scampered down the trees, and after a while they learned to leave the trees alone.

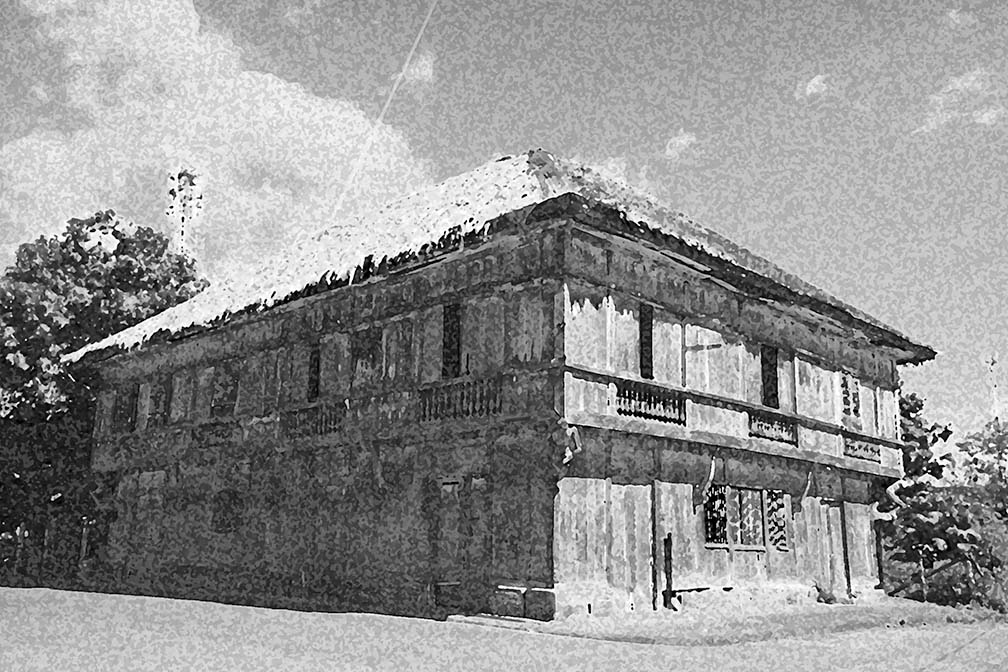

The soft dappled shade served many purposes. The branches sheltered a group of nursery school children with sausage curls whose playground had been turned during the Occupation into a garrison. In the afternoon, a Japanese girl named Sato-san came to air a nephew and a niece and lay out rice cakes under the spreading trees. She was a masseuse in the Japanese barbershop at the corner which was always brilliant with neons and sweet with the odor of Bay Rum. Occasionally, a dispossessed family of tattered jugglers did their act in the shade of the acacias. They laid a dirty tarpaulin on the ground and tumbled in it, juggling wooden balls and bottles. Then the father stood on a barrel and balanced his two daughters on his shoulders and it was the most daring, most brilliant finale I had ever seen. As they made their bows, an indifferent crowd dropped a coin or two into the man’s soiled hat, and once I saw someone drop in a rotten mango.

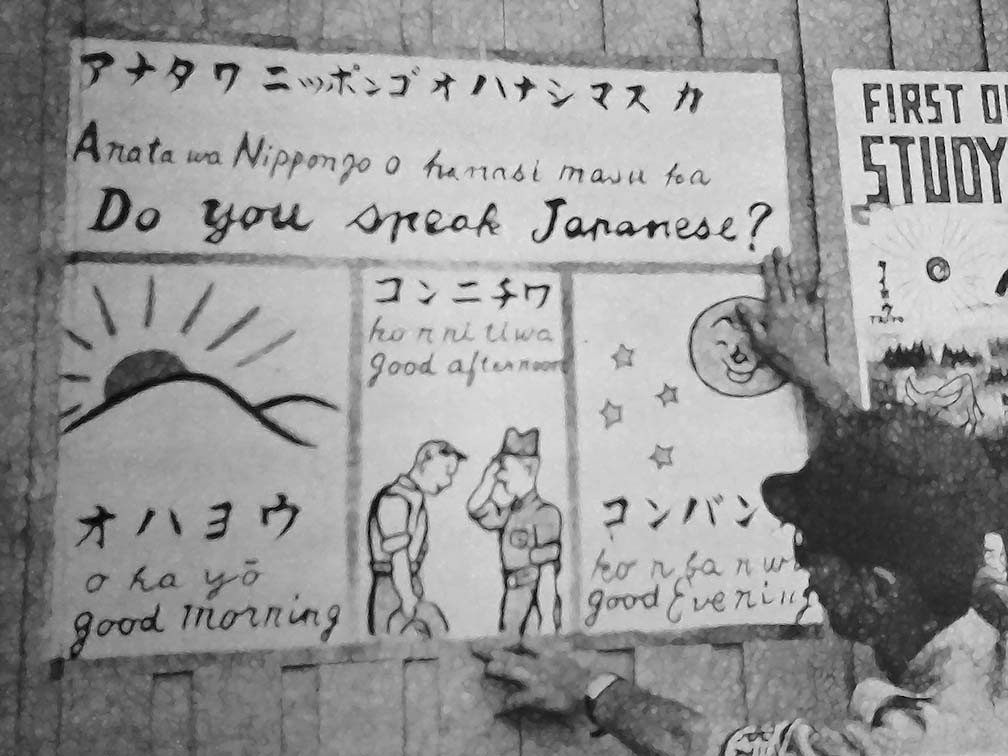

Our driver now turned houseboy (our Plymouth had been commandeered) hailed from a pot-making region and he would come from vacation with a tobacco box full of hard day pellets baked in the sun, for my father’s slingshot a year’s supply till the next vacation. My father had a low opinion of the Imperial Army. When I showed him my report card, he thundered. What do you mean 75 in Algebra, 95 in Nippongo! Am I raising a little geisha?

Oh yes. one night he almost got into real trouble with that slingshot. A drunken Japanese officer was kicking noisily on the door of the family living downstairs, calling the young girl’s name amorously and growling like a jungle ape. Annoyed, my father flung back the bed sheets and charged to the window with his slingshot. Mother tried to pull him back, but already father had aimed and hit right in the seat of the olive drab pants. It was blackout and the man was at a disadvantage flattened behind the window, his treacherous opponent let loose another hail of pellets. With a horrible war cry, the soldier unsheathed his sword, a grim Samurai brandishing reprisal in the air. Mother and I cowered in our nightgowns and embraced each other. Whenever the officer’s drink-clouded eyes looked up at our direction, my father shot at him from another window. Finally, he stumbled away, his hobnailed boots echoing in the deserted midnight street. We half-expected the Imperial army to storm our door the next morning. But they never came, I guess the officer was too drunk to remember it.

After a while our curtain of trees became useless. The people on the other side of the river raised a contribution to build a bamboo bridge across it and the bad elements started coming into town. It was a narrow, split-bamboo bridge that swayed, and the Japanese soldiers loved to walk on it.

As the beggars with coconut shells in their palms increased in numbers, it became a usual thing to find a bloated corpse under a newspaper. Everyone was suddenly interested in food production: twin curly-haired young men from across the river began to cultivate the ground surrounding the acacias. From two o’clock until sundown they puttered among the neat plots, loosening the soil around the flourishing yams and talinum buds, fetching water in cans, collecting fertilizer from under the dokars parked in the street. Aquilino was the leaner, handsomer twin, he was my brown god in an undershirt, reeking of sweat and fertilizer; but when Santos knocked on our door with a basket of talinum tops for Mother, I couldn’t decide whom I liked better. When the jasmine climbing from our window box was replaced with the more practical ampalaya, I carved their names on the fruit, and the letters grew as the fruit grew: Santos and Aquilino.

II

The Spanish family renting the downstairs portion of our house opened a small laundry but retained their fierce pride. The women sat behind the unpainted counter in their bedraggled kimonas, like soiled aristocracy, handling the starched pants drying on the wire hangers with pale finicky fingers. They pretended to understand nothing but Spanish and a customer’s every Tagalog word sent them huddling together in consultation. If you were overtaken there by lunchtime, in the kitchen Señora Bandana placed a wet rag on her hot frying pan. The daughter then came out and said wheedlingly, Cena tu ya aqui, having made you believe, by the fabulous sizzle that there was a chicken or at least a milkfish in the pan. Since it was unthinkable to stay over for a meal during those hard times, you left with thanks and profuse apologies. The family then commenced on its meal of rice and bagoong, smugly sitting on their reputations.

They had been paying P15 a month before the war and insisted on paying the same rent in Japanese money. My father continually begged them to leave so we could take in boarders, but whenever he brought up the subject, Señora Bandana had one of her heart attacks. Finally, they compromised by giving us back two rooms which we needed for Mr. Solomon and Boni.

Boni was a fourth cousin from Batangas on my mother’s side. He had gotten stranded in Manila when the schools closed and came to live with us because he found it easier to make money in the city, on buy-and-sell. He always had some business or another:

He had converted an old German bicycle into a commercial tricycle and rented it to a man every morning. He also dealt in wooden shoes, muscovado, agar-agar and cotton batting for auto seats. On father’s birthday, Boni presented him with a skeletal radio he had tinkered with, that could catch the Voke of Freedom and it pleased my father no end. Once Boni bought three truckfuls of bananas wholesale—our garage was so full of them there was hardly any space to walk. That venture had been a fiasco— before he could resell the lot, half of them rotted away while he was at a dance in Paranaque.

Boni was an expert balisong wielder. He could hit a coin four feet away, the knife making a clean hole in the center of it. He also had a bad habit of throwing the knife at cockroaches and lizards and cutting them to ribbons. Once he threw it at a stray cat that was annoying him below his window and my mother almost had a fit. Send him away, my mother told my father over the tulya broth. Make him go home to the province. My father took the knife away and told Boni to behave. Boni’s father was an unbeliever, and when he died, which was three years before the war, he asked the family to erect a devil on his gravestone. And there it still stands in the cemetery in Batangas, regal and black, its tail long and sharp as an arrow, its eyeballs and armpits a fiery red, lording it over all the weeping angels and white crosses. On All Saints’ Day Boni alone came to visit the grave to cut away the weeds and repaint the devil a deep glossy black.

Mr. Solomon occupied what had been Seriora Bandana’s sala. He hung up his crucifix and his hat and locked the door and never opened it again. Mr. Solomon owned vast salt beds in Bulacan and his dream was to control the salt market in Manila. Just before the war he was competing even with the Chinese merchants and whatever price he dictated the merchants had to follow. In the great salt war there was a time when salt was selling for ten centavos a sack.

His four sons joined Marking’s Guerillas after the fall of Bataan, and Mr. Solomon became its heaviest contributor. The Japanese had seized his salt beds and when he became the kempetai’s most hunted man, he begged my papa, who was his old friend, to hide him and that was why he was boarding with us.

Mr. Solomon stayed all day in Señora Bandana’s sala, gazing out the window saying nothing. He listened to the nursery school children singing; he watched Sato-san air her nephews and nieces: he dropped coins into the juggler’s hat. But we had to pass his food down a wobbly dumb-waiter. My brother Raul and I complained whenever we were assigned to deliver the food, especially if there was hot soup, but Mother said to be patient with Mr. Solomon as he was a man who had ‘gone through the fire of suffering.’ The only time Mr. Solomon ever went out of his room was when he offered to show Papa how to make ham. After rubbing the fresh pig’s thigh with salt, he brought out a syringe and shot the red meat full of salt-peter and other preservatives. Then he wrapped it in a cloth and told Mama to keep it in the ice box for three months. Mama said Mr. Solomon was probably getting tired of eating fish.

When Eden and Lina came to stay with us, I gave up my room to sleep with Mother. They were home-loving sisters who made my room look nice with printed curtains and put crotcheted covers on the beds. Under the bed they had many boxes of canned goods, mostly milk for Eden’s baby. A basket lined with diapers was hung from the rafters and the baby slept in it.

Eden and Lina’s father was Papa’s brother and they used to live in Cabanatuan where they had a rice mill. As children, we used to play baseball on the area of cement beside the granary where the palay was spread out to dry, during our vacations in the province before the war. Their mother ran a restaurant called “Eden’s Refreshment,” where she served a thick special dinuguan smiling right from an earthen pot. Tia Candeng had a fault—she played favorites. It was always ‘Eden is pretty, Eden is valedictorian. My child Eden . .’ Never Lina. Lina ran around in ragged slacks and played cara y cruz with the mill hands. On Eden’s eighteenth birthday they rented the roof garden of the municipia and held a big dance. Her dress was ordered from Manila and cost three hundred fifty pesos. The town beautician worked all day putting pomade and padded hair in her pompadour. They sent us an 8” x 10” photograph of Eden on her debut with a painted waterfall in the background.

After that, a rich widower used to motor all the way from Tarlac to visit Eden. An engineer also fell in love with her and lavished the family with bangus from their fishpond. When the charcoal-fed Hudson and Ford stopped by their gate, Ira Candeng, all a-flutter brought out from her stock of pre-war goods precious hot dogs to fry and serve to the rivals. But one day a small squat soldier without a job blew into town and Eden ran away with him. He was a mere lieutenant and a second one at that, and Tia Candeng never forgave them. They came to the city to live, in a muddy crooked street. Minggoy and Eden had violent quarrels. Whenever they did, Eden bundled her cake pans and pillows and mats and photo albums and the week-old baby and stayed with us for a few days. In the latter part of the Occupation, her husband joined the guerillas and Eden came to live with us permanently.

Lina came later. Her stringiness had blossomed into a willowy kind of slenderness and she had her mother’s knack for housekeeping. But she was of a nervous temperament. Continually, she wove “macrame” bags of abaca twine in readiness for the day when we would be fleeing the bombs. She had also fashioned a wide inner garment belt of unbleached cotton, with numerous secret pockets.

III

My brother’s room was the largest in the house, it was the size of the sala and the dining room together because in the good old days it had been a billiard room. It let out to an azotea and had a piano in it. His friends, Celso, Paquito and Nonong were always in Raul’s room for they were living to put out an ambitious book of poems. Celso’s father had an old printing press, rusty from disuse, and they lugged it up to the room and were always tinkering with it, trying to make it work. Boni offered them a price for the scrap metal, and they threw an avalanche of books at him.

The piano had been won by an uncle of Nonong, who was timbre-deaf, from a raffle. This uncle was so timbre-deaf in fact that the only tune he could tell from another was the National Anthem, because everyone stood up when it was played. All he had to spend for was the ticket and the transportation, and on Nonong’s birthday the beautiful second-hand Steinway was presented to him instead of the books he wanted. Nonong’s room was too small for the piano, and so of course it ended up in Raul’s room. Mother never objected to the boys lugging things into the house just as long as they never lugged things out.

Sometimes they stuck a candle in a bottle and my brother Raul read the Bible deep into the night. They called me their muse and allowed me to listen to their poems for I had read Dickinson and Marlowe and of course that made me an authority, and besides I was always good for a plateful of cookies or to fetch an extra chair. Paquito could play “Stardust” on the Steinway and Cels could do a rib-splitting pantomime, but best of all I liked Nonong although he couldn’t do anything. Nonong gave me a Ticonderoga pencil he had saved all the way from before the war—it was stuck on a painted card where you could read your fortune. On Christmas I gave him a handkerchief embroidered with his initials in blue thread.

Nonong was always trying to make an intellectual out of me. The few books I read Les Miserables, Rosahomon, Gruustark and Inside Africa were all from him. I ransacked my father’s trunk of books for something to present him in return and came up with the fourth volume of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, from John the Baptist to Leghorn. I have read a lot of authors, Nonong used to say teasing me, but best of anything I’ve read I like the Encyclopaedia Britannica, from John the Baptist to Leghorn. Once, after a visit to a friend’s house, Raul couldn’t fetch me and my mother telephoned. Don’t go home alone. Nonong is here. I will send him over to fetch you. We walked-down the avenue laughing under the unlighted street lamps, the carretelas and tricycles zigzagging past us.

Let’s drop by your office, Nonong, I said. So you can get the book you promised to lend me.

All tight. Nonong said, although there’s not much print left to read any more—the Bureau has inked out all the nice pages and covered the pictures.

That’s all right. I said, flinging my arms in a bored gesture the way I had seen movie stars do. It’s better than dying slowly of boredom.

Are you lonely, Victoria?

No. I said defiantly, deep in my heart, lying.

We walked.

We turned into the stairs of his office in R. Hidalgo St. over which was a sign in Japanese characters. The back of the building had been bombed out and no one had bothered to clear up the rubble. There was a blackout notice again that night and it was pitch dark in the building. We groped our way to the head of the stairs and into the room. There were five desks and Nonong’s was the farthermost, under the electric fan. Kneeling, Nonong opened each drawer and ransacked its contents. It’s here somewhere, he said.

I went out to the little balcony and stood looking down at the gradually emptying street. It was four days before Christmas. There were paper lanterns hanging at the windows of the houses but none of them was lighted, and they swayed, rustling dryly in the cold wind. I was tired of the war. I wished Nonong would put his arms around me and kiss my lips and always love me, but I knew that if he even as much as touched my hand I would slap him hard on the mouth and kick him on the shin and never speak to him again. He stood silently beside me and put his lean arms on the window sill, I could see the veins taut on them. Behind us, the darkness was absolute and complete.

What are you going to be after the war, Nonong?

Oh…a writer, I guess, or a bum or something.

Me, I’m going to buy a house on top of a hill and live there all my life alone.

Suppose someone falls in love with you?

Who’s going to fall in love with me, silly?

I looked up at the stern profile etched in the dark, thin and beautiful and ascetic, like the face of Christ. Heavens, Nonong, I exclaimed. You look like God!

Don’t be blasphemous. Victoria, where’s your convent school breeding? He smiled. I’ve got the book now, let’s go if you’re ready.

We felt our way through the pitch-dark corridor to the stairs at the foot of which was the door in a well of smoky lights.

We were the lost generation: My brother Raul and his friends were neither men nor boys, they were displaced persons without jobs and they roamed the streets restlessly in search of something useful to do. My father had started a business making oil lamps and the boys helped him in the mornings, cutting the glass and hammering open the tin cans and shaping them in the vise to fit the pattern. But their afternoons were empty. Nonong and I learned to lag behind after church and walk, nibbling roasted coconuts that tasted like chestnuts when we were together. Sometimes I went with the Gang to the Farmacia de la Rosa where we could order real fresh milk ice cream. Mrs. de la Rosa told us her fresh milk came all the way from Pampanga every day and had to pass four sentries and that was why it was so expensive. Sometimes we went into a “Tugo and Pugo” stage show to buy an hour’s laughter at other times we rented bicycles and rode to the very end of town where nobody knew us, peeping over the fences of Japanese garrisons with the flag of the Rising Sun fluttering over it.

One day I told my mother that Nonong was coming that afternoon and if I could ask him for supper. I slaved over a plateful of cassava cookies in front of a hot tin charcoal oven. Lina was the good cook but I disdained her help and advices. For supper we had fresh tawilis from Batangas, and a good piece of the ham that Mr. Solomon had made. We waited for an hour past suppertime and still Nonong had not come. When we ‘finally did sit down for supper, nobody said anything except for Boni, who, having arrived late, looked at the extra plate quizzically, opened his mouth and closed it again like a fish gasping for air.

It was raining when Nonong came, smelling of beer, three hours late and sorry. I had already put away the supper dishes and cassava cookies I had sweated over all afternoon, and I was still angry. He sat on the large kamagong chair and I sat on the other kamagong chair opposite him, with the vase of santan flowers between us. And then we looked at each other and stopped dead still. For we could feel each other’s hearts and knew what was there, what had been growing for months without our knowledge and consent And heavy with grief I said simply, I dreamt of you last night. You were sitting on a chair and I was on the floor hugging your knees and I said I love you, and you said, that’s all right you’ll get over it.

He put out his fingers tentatively and stroked the back of my hand and I pulled it away. But in a minute we were touching again and I was crying into his palm and he said, Help me, I’m so unhappy. But after a while we heard Eden’s slippers slapping on the floor of the dining room when she had gone to open a can of milk for the baby, and I told him to go away and never see me again.

On February 17, Nonong telephoned me. We talked a long, long time about this and that and many useless things. Then just before the Japanese cut off our line, I heard his voice at the other end say soft but clearly, Listen to this, Victoria, and remember: l-love-you, and that was the only time he ever said it.

IV

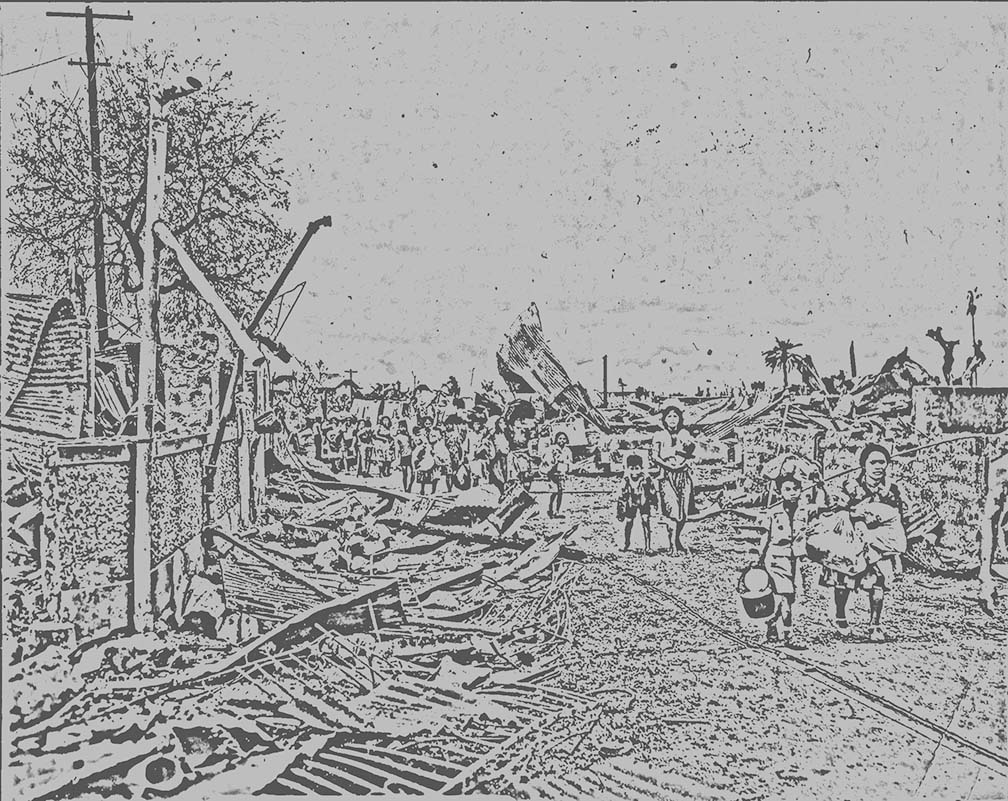

We had run to the church rotunda and even there the dugouts were every place, you were lucky if you could find a place to dig. The house had burned down and Boni had gotten burned trying so save Mr. Solomon who had panicked and couldn’t get himself out of his locked room. Father and Raul were carrying Boni in a blanket fashioned into a hammock Lina and I walked together—she had on her belt in which were all her treasures, and the six string bags with clothes in them. I was carrying my favorite dress, a pillow and a bottle of precious water. Immediately behind us Eden walked with the two-month-old baby in her arms. Mother walked last of all, pale and tight-lipped, carrying the kettleful of rice she had boiled for the Monday meal and the slices of roasted pork. From Taft Ave., you could see clear through to the seashore for all the buildings were charred and rutted. The Japanese had barricaded themselves in the Rizal Coliseum and you could hear the mortar shells go boom-from there and boom again a mile ‘away.

A trio of planes roared dangerously low. Shakily, Lina and I dived into a shelter where a Chinese consul and his family crouched, and bitterly, they reproached us for crowding them in the already cramped space. Mother had run into another hole and ran out screaming for there was in it a man with half of his face shot off. Outside the shelter, we could hear Boni begging, please don’t leave me…We were scattered in all directions.

Somehow we found each other again. Papa’s plan was to go south to Pasig to escape the mortar shells that were coming from the north. He and Raul took up Boni again and started to walk. Somewhere in the running. I had lost my shoes and was proceeding barefoot, I had also forgotten my favorite dress in the last dugout.

Whenever the mortar shells dropped around us, we threw ourselves flat on the ground and covered our ears, but still we could hear the whistling and the unearthly screams of the people who had been hit. After one of the raids which lasted longer than usual, we burrowed out of the shelters to find Boni gone. Someone told us later that he had been seen crawling to Taft Avenue.

On our way to Pasig we scampered for safety into the old Avellana home, the only one standing in Malate. A Japanese sniper in a battered car was shooting at us and we went into the enclosed ruins, picking our way hurriedly over the wounded and the dead. Raul was the calmest of all. He had taken the kettle of rice from Mother and whenever he dived to the ground, a little of the rice spilled but he gathered it again, brushing the earth from the pork with invincible good humor. He had his rosary with him and never parted with it, he vowed that if nobody got hurt he would become a priest.

We entered the damaged cellar and found there a group of hysterical mestizas. One of them, Señora Bandana’s daughter, a friend of Lina’s, persuaded her that the place had been continuously machine gunned and that they should transfer to a concrete garage nearby where the rest of the family were. Lina left with her. We were willing to take our chances and remained behind. We settled ourselves comfortably, taking small swallows of water from our bottle, but not one of us could eat. The baby sucking at Eden’s breast was drawing blood and Eden’s tears were falling on its face. In a few moments Lina was back alone. She was hysterical. The garage she and her friend had gone into had been hit by a grenade, and she had seen the whole Bandana family and her friend perish in it.

We ran without any sense of direction. Finally, we found a high concrete wall against which several galvanized iron sheets had fallen, forming a safe shelter, but every time someone moved, the sheets clattered noisily, betraying our presence. The few remaining Japanese soldiers were desperate: with bayonets bared, they stalked the ruins, thirsting to run through anything that moved. Raul pillowed his head in his arms and snored like a baby. We heard a Japanese soldier patrolling nearby, his hobnailed boots crunching heavily on the rubble. Eden’s baby began to whimper. Eden offered her breast but the baby refused it, for it could no longer give any nourishment. Keep him quiet, my mother hissed. The footsteps were growing fainter and then they stopped altogether. We heard a revolver cock. The footsteps started again, trailing the same path outside our shelter. The baby was now whimpering in earnest. Beat its head with a bottle, somebody suggested. The bottle was thrust in Papa’s hand. He raised his hands for the blow and brought them down limply, he had a weak stomach. He tried next to strangle the tiny neck but his fingers turned weak and rubbery. The soldier was almost upon us. Luckily, the baby quieted for a moment.

Only when the footsteps receded could we talk. Papa said, Eden, go away with your child and save us, and maybe you too can be saved elsewhere. Eden crept out slowly, making an infernal racket with the sheets. In a moment she was crawling back. Wordlessly, she turned over the baby to Papa like an offering. The Japanese was returning. Lina cursed, restlessly she paced back and forth, standing up and sitting down. I’ve got it! she cried, let me…She took the pillow I had been carrying all this time and put it on the baby’s face. Then she sat on it, hard. The mother stared dumbly at the earth, her hands dangling between her legs. There was a struggle under the pillow and a smothered whimper. Slowly, Lina got up, biting her nails. She became hysterical and Papa had to hit her across the mouth. Eden took the dead baby and began rocking it to sleep.

We slept from exhaustion, the crunching footsteps had disappeared. The moon rose bright and clear. like the promise of another time, and we could find our way out. A group pushing a wooden cart full of pots and pans and mat bundles were coming towards us. The Americans are here, the father of the group we met said. They have gone over Santa Cruz bridge. Papa counted the heads. Boni was gone. Mr. Solomon was gone. We couldn’t find Eden. We looked back to where we had come from and through the twisted steel buttresses of the ravished homes, we could see a lonely figure poking amid the debris.

She has probably gone back to bury the child, Mother said. Let’s go ahead then, Father said. She’ll catch up with us.

This copy was sourced online from The Well of Time: Eighteen Short Stories from Philippine Contemporary Literature (Compiled by Teresito M. Laygo)