Lualhati Bautista is one hell of a woman. Her quite ordinary face, her typical brown skin, and her average height of about five feet one inch do not intimidate. But she looks at you straight in the eye with that no-nonsense expression. She’s very observant, a good listener, and can be brutally frank. Her steps are not hurried, but her gait is sure. She’s comfortable in t-shirt and jeans and rubber shoes. She smokes and loves to dine out and drink with true friends.

Some people are frightened by her—those who have crossed her one way or another, maybe during her bad-hair days when she can’t perform as a superwoman, because she has no maid and she has to meet a deadline while doing house chores or when a person has done her wrong or when she has no money.

She doesn’t look for trouble, but she’ll stand up for her rights and for her principles even if these go against the perspective of most or of leaders or of critics—the very people who may be in a position to pull her down. Lualhati doesn’t care about wearing a mask or being a goody-goody toad. This, however, doesn’t mean she’s rude, she’s merely being true to herself.

Others adore her for her writings. Students line up for an interview with her for a school paper or a thesis. Her short stories and novels are taught in schools, and are widely anthologized here and abroad. Her books are sold out. Movie fans seek her autograph. She commands a price for her scripts without the help of an agent. She is hired for film and television for both award-giving festivals and commercial movie runs.

Still, others simply take her for what she is: writer, mother, woman, friend.

Lualhati Bautista, or Iné to family and relatives and very close friends, is perhaps the only living woman, at least, of her generation, who is not wealthy, who lives solely on her creative writings. True, she had a brief stint for a few months in 1987 as columnist writing “Woman Power” in a Filipino broadsheet, Daily Mirror. She also wrote a series of feature articles on a correctional institution for women in Kislap magazine in 1969. But hardly anyone remembers or has read those journalistic ventures of hers.

She also worked in 1988-1990 as translator for Solidarity Foundation, Inc., wherein she translated several books such as Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Rashomon at Iba Pang Kuwento; S.D.B. Aman’s Kuwentong-Bayan mula sa Indonesia; Si Taw at Iba pang Kuwentong Thai, edited by Jennifer Draskau; and Masanobu Fukuoka’s Isang Dayaming Rebolusyon. These income-generating projects, however, were along her creative line. They provided her further challenge with the use of language and imagination.

Ever since she could remember, Lualhati had always wanted to be a writer. As a child, she would wake up to her father’s guitar and violin playing. Her father, Esteban Bautista, composer, singer, and poet, had a record album of songs he composed and sang being played on the radio. Unfortunately, says Lualhati, she doesn’t know the title of the album nor could she find a copy of the record.

Listening to music was thus second nature to her. She would read and listen to stories while her mother, Gloria Torres, a Manileña who grew up speaking Spanish, and got married at 17, reared nine children and attended to housework full time. Although Papa Esteban helped in the house, it was Lualhati’s mother who tried to make ends meet, what with the meager and erratic income Esteban was making in his buy-and-sell business.

A free spirit tagged as “Binatang Maynila,” his father was about the go to Guam as a band member, but the trip failed, and he sold houses and lots, and even typewriters. Perhaps because he knew his second child Lualhati took after him, he did not dictate on his daughter what to do. And when father and daughter would quarrel, she would have the last word, and he, the father, would play the guitar to assuage his child’s anger as well as to control himself.

Lualhati finished primary education at the Emilio Jacinto Elementary School in 1958. Then, in 1962, she graduated from Torres High School in Gagalangin, Tondo. She took up Journalism at the Lyceum of the Philippines in 1964, but didn’t complete the second semester of her first year.

Even as a spunky tot, she hated being confined in a classroom. She was impatient with regimented study and unintelligent teachers. “Ba’t kelangang ang titser ang magdeklara kung kelan ang holiday?” she complained. She was bored to death. Hence, in college, she dropped out. She dropped out because she wanted to write. And write she did from then on until now.

Her first short story, “Katugon ng Damdamin,” came out in Liwayway, the leading magazine in Filipino, dated November 25, 1963. She was paid P60 before the issue in which her story appeared, and she was given an advance copy. When she showed her published story to her father, her father was so excited. Recalls Lualhati, “Hindi yata nakatulog para sa umaga susuyurin ang mga stand para bumili ng magasin. Binili niya lahat ng makita niyang kopya at ipinamigay sa lahat ng mga kaibigan niya.” She was 16.

At first, she would mail her stories, but rejection slips from Bulaklak and Tagumpay would be mailed to her, and her cousins would receive the slips and tease her. So, afterwards, she would deliver stories personally to the editors so that no one would know if she got rejected.

“Pag binabalikan ko ang mga kuwento ko noon, nahihiya ako,” muses Lualhati. “Siyempre, bata pa ako noon, sinusulat ko’y iyon lang karanasan ko, iyong nalalaman ko bilang tinedyer. Pero di ko naman itinatakwil dahil tingin ko, kahit bata pa ako noon, may kahusayan naman ang pagkakasulat ko, may estilo na ako.”

Young though she was, she was in the company of Liwayway Arceo, Levy Balgos de la Cruz, Susana C. de Guzman, Efren Abueg, Elena M. Patron, Ave Perez Jacob, Josefina Corpuz, Rogelio R. Sikat, Erlinda Namera, Domingo C. Landicho, Edgardo M. Reyes, and others.

They were spoiled, according to Lualhati. She got published almost every week. “Pag nare-reject kami noon, kakain kami sa canteen, tapos, ipapalista namin sa pangalan ng mga editors ang kinain namin (si Clodualdo del Mundo Sr. ang editor noon).” And the Liwayway office on Soler Street was second home to Lualhati and her group. They would sleep there and type and help proofread their own stories.

Writing, however, was not the only obsession of this young lass from Tondo. Her other obsession at that time was Levy Balgos de la Cruz. He was her schoolmate, who was three years her senior. Although his younger brother was her classmate, she wouldn’t dare tell the brother nor could she insert a love note in Levy’s notebook. It just wasn’t done, for she was female. And this she questioned, though she kept quiet, not knowing what to do to make her feelings for him known.

Until they were both Liwayway habitués, until her intense and good-looking crush finally took notice of her stories. They became friends. “Plano ko noon mag-asawa kay Levy at magkaanak,” reveals Lualhati, “Nagdi-DG siya sa mga kaibigan ko, nakikinig ako. Tapos, sabi niya, ‘Sasama ka ba sa akin?’ ‘Oo, sasama ako sa iyo kahit saan.’ Siyempre, sabi ko lang iyon dahil kung hindi ko sinabing sasama ako, di na niya ako isasama.”

The barkadahan led to elopement and the two got hitched in 1969 in Abucay, Bataan. The wedding was officiated by the vice-mayor of Abucay. Even from the start, however, she sensed that her marriage wasn’t for life. “Feeling ko, maghihiwalay din kami. Ang tingin ko, ang kasalan ay kasalan ng dalawang lalaki. Pabor ang tatay ko na magpakasal kami. Sabi niya sa akin: ‘Di ka pa magulang ngayon, pero maiintindihan mo pag magulang ka na.”

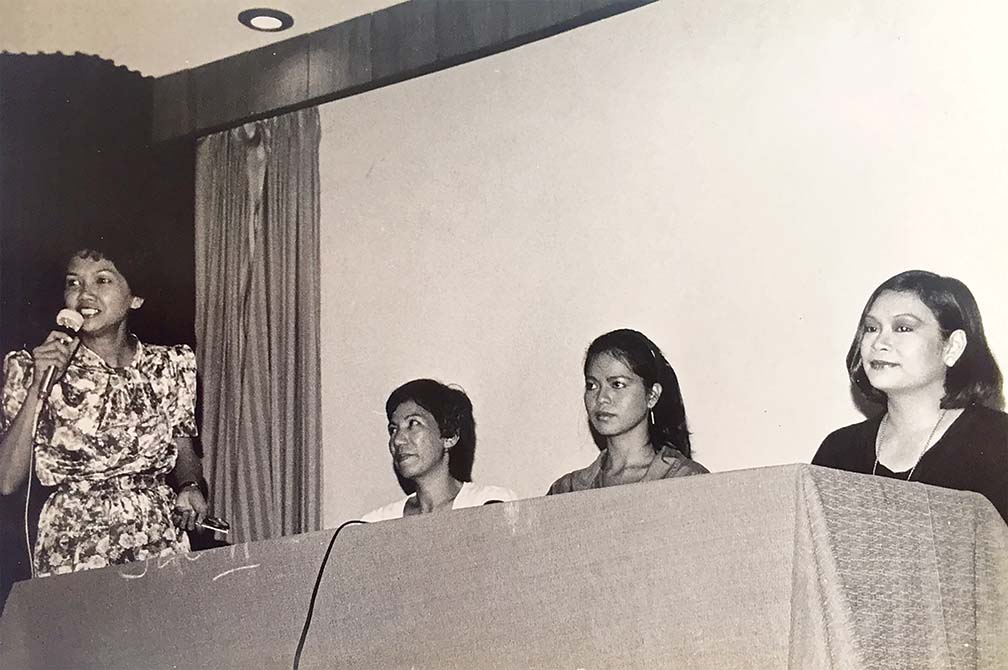

poet Ruth Elynia Mabanglo, Julie Lluch, Lilia Quindoza Santiago, Teacher and writer Chari Lucero,

and Lualhati Bautista

As a wife, she felt that “para akong laging nasa shadow. Ako iyong nagta-type ng stories niya para sa Liwayway, at ng Palanca entries niya. Siyempre, ako, may negative traits din ako, may kasalanan din ako. Pero marami kaming hindi swak. Hindi siya good provider. Nagsulat ako para magkaroon ng pera.”

In the early days of martial law, she went with him, but soon left him, pregnant with Dayang, her second child. “Di ganoon ang buhay ko, na parang regimented, unnecessary sacrifice, walang privacy, pati mga personal na problema, pinag-uusapan. Umalis ako sa lugar nila ng kilusan pagkaraan ng ilang buwan. Iniisip ko, puwede ka namang maging effective sa ibang paraan para magkaroon ng pagbabago sa lipunan.”

She turned single parent and continued to earn a living by writing. She broke into television in the 1970s by doing scripts for various TV series directed by Orlando Nadres, by Lucio Maylas, and by Lino Brocka. In 1976, she co-wrote with Oscar Miranda the screenplay of the critically-acclaimed Sakada, megged by Behn Cervantes.

Then, one day, she thought of doing a novel and entered the Palanca literary contest just to find out if she could really write. If she lost, she would stop literature and go into another field. The novel Gapo won the 1980 grand prize. She was ecstatic. Her live-in partner bought her a new dress and a cousin lent her a diamond ring to wear at the awards night. She couldn’t understand, however, why the pressure to dress up and go up the stage. “Parang nape-penalize ako for a work well done.” She went up the stage, anyway, and received her prize.

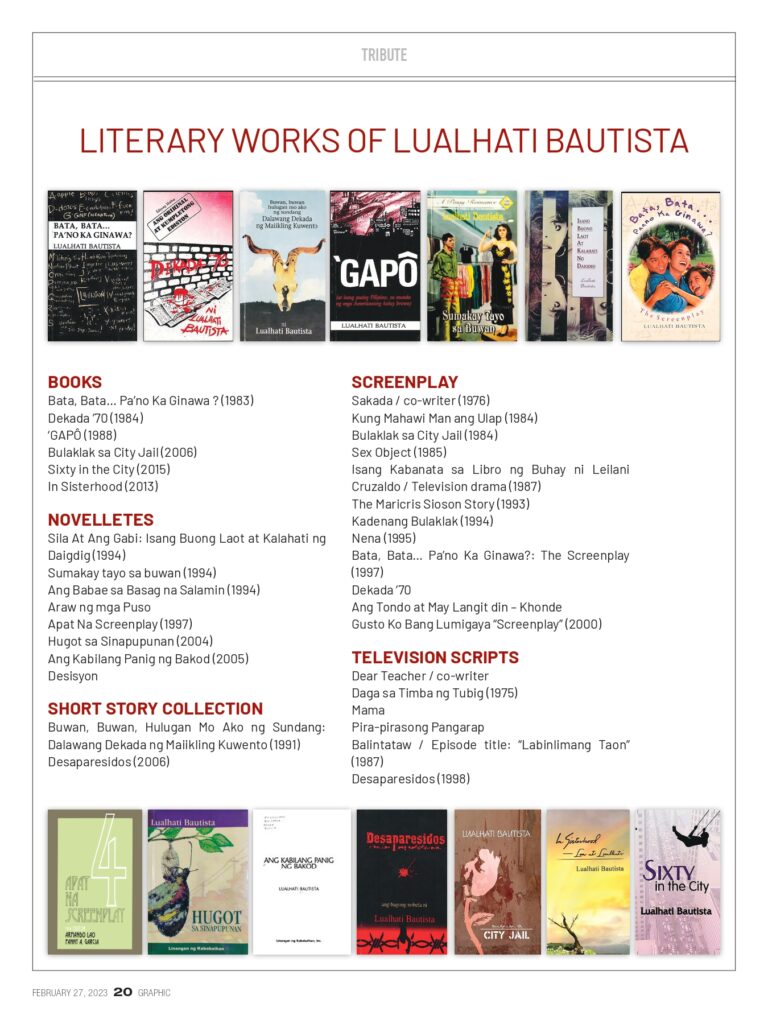

To satisfy her curiosity as to whether her first win wasn’t sheer luck, she joined the Palanca tilt with a second novel, Dekada ’70. She obtained another grand prize in 1983. She entered the competition again in 1984, this time with Bata, Bata…Pa’no Ka Ginawa? Again, she garnered the plum. “So,” she said to herself, “hindi na talaga tsamba.”

Lualhati went on to reap more awards as fictionist and as scriptwriter for film and television. Who can forget Mario O’Hara’s Bulaklak sa City Jail, her first solo script, which won best story and screenplay in different film awarding bodies? Her adaptations of her own works, Bata, Bata, Paano Ka Ginawa? (1997) and Dekada ’70 (2002), both directed by Chito Roño, are highly memorable.

In the 1980s, she was earning more than P100,000 a month, and she moved with her children from Tondo to Quezon City. She rented a nice house, was the flavor of the month of respected directors, and tasted a bit of the good life. Now, she has a modest house and lot of her own in Fairview.

Showbiz rewards, however, come and go. There are times when scriptwriting offers are scarce or when the projects are unappealing or simply do not materialize. The wheel of fortune allows her at one time to splurge on refurbishing her house, then, the next time it forces her to scrimp and save for her children’s enrollment or for the monthly installment of a lot she acquired somewhere.

She has also had a taste of showbiz controversy. As the writer of Sutla, directed by Romy Suzara and starring Priscilla Almeda, Lualhati was criticized. How could she, a known feminist, be involved in such a “pornographic” film as Sutla? It is “bold” because of its nude and lovemaking scenes. But it is also bold because it is one of the most subversive films in the history of local movies. Why? Because it shows that women have the freedom to enjoy sex as well as the right to say No.

Sutla may not be the first film to tackle woman’s sexuality. There have been Divorce, Pilipino Style and Babae, Ngayon at Kailanman as well as a host of director Mao Guia Samonte pictures such as Machete, Basa sa Dagat, and Gigil. Sutla stands out, however, because here, the woman consciously controls her body without the guilt imposed by a patriarchal society.

Controversies notwithstanding, Lualhati Bautista’s writings have brought her abroad such as being invited as delegate to the United States by the USIS-International Visitors Program/Multi-regional Project on Film in 1994. Also in 1994, she was given the Outstanding Women Artists Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 1999, the Gawad Pambansang Alagad ni Balagtas, National Achievement Award for Literature.

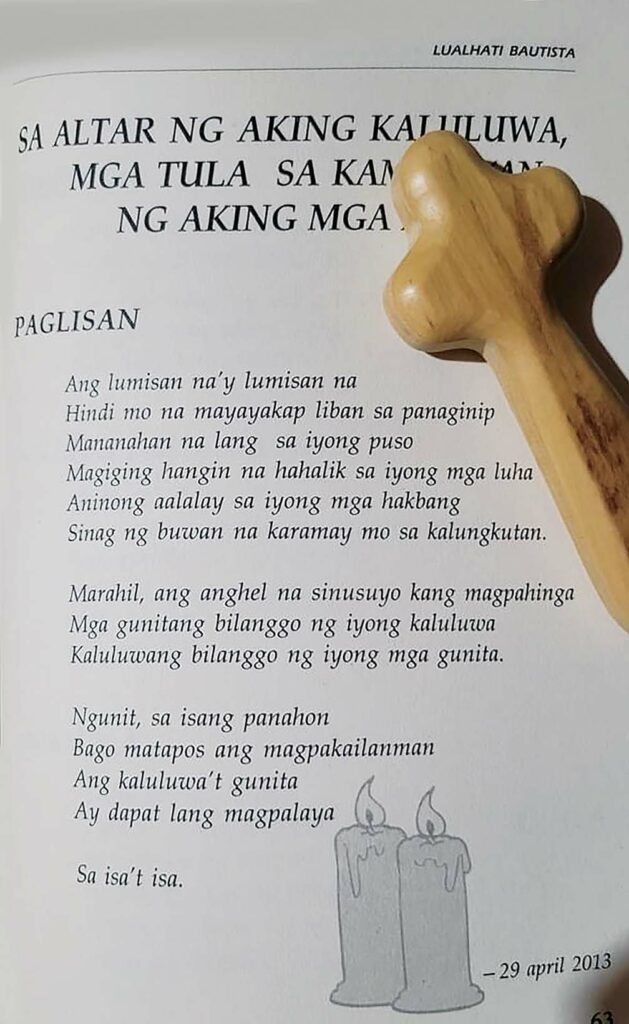

Her plays have been staged, and her poems have been published in national publications as well as anthologized. She has edited and written best-selling romances. She penned more than a dozen teleplays for Gina de Venecia’s Pira-pirasong Pangarap, which deals with the plight and human rights of women and children.

Her politicization was heightened in the women’s movement. She has been a member of feminist non-governmental organizations like Concerned Artists of the Philippines-Women’s Desk, and of Women Creating Cultural Alternatives (WICCA). Why women?

“Bata pa ako,” Lualhati states, “marami na akong tanong. Halimbawa, noong elementary, bakit pag lalaki ang tumatalon sa flower pot, hindi pagagalitan ng titser? Bakit pag ako, pinagagalitan ako? Ba’t di ko magawang mag-insert ng sulat sa notebook ng crush ko? Sa filing ng income tax, mas mabuti pa ang single. Pag married, hinahanap nila ang suweldo ng asawa as head of the family. Noong minsan, umuwi ako ng bahay alas-siyete ng gabi, wala si Levy, tinanong ako ng biyenan ko, saan daw ako nanggaling, ba’t ako ginabi, ke babae kong me asawang tao…pero pag lalaki ang ginabi, okey lang.”

She admires her mother, though, for working hard as a homemaker, and her maternal grandma for being a strong woman. The spirited Lualhati, however, is not fond of cooking and washing dishes and will never cease griping and asking questions. Although she attends to her grandchildren, and sometimes wishes she had a constant companion whom she can talk with at night, she prefers to be independent. “Pag may asawa, maraming demands, maraming expectations.”

Her marital status is another issue. When she applied for a passport, her year of birth was miscopied as December 2, 1946, rather than 1945. And because she was asked for a marriage contract, she avoided the tedious process of getting a copy of her contract, and so, she just put down “Single.” Besides, she thought, it was her own decision to get a passport and to travel, what did her husband have to do with that decision of hers?

Again, when she was to sign an agreement with Books for Pleasure, Inc., as a writer of Valentine Romances, she was surprised to see Gilda Olvidado, another fictionist, bringing along her husband Ruben. The law requires, they said, that the husband should also be present to sign the agreement. Lualhati felt injustice: “Utak at talino ko ito. Ano ang kinalaman ng asawa ko dito?” Hence, her status remained “Single.”

When she was getting a loan from a bank, she was asked whether she was married or single. Why on earth, she pondered, did she have to get the permission of her husband for every act that she did? Again, she answered: “Single.”

Her literary creations are her outlets, her darlings, her personal symbols of what she can achieve, her contributions to society. Whatever she does she drops when the muse sings, and especially when money calls. Are the children hungry? They can cook or go buy themselves food at the carenderia or fastfood. Is the house a mess? Never mind. Are there dirty clothes to launder? She kicks them under the bed. Are there VIPs or whoever to talk to her? She’s out of the house or out of this world.

If given a choice, all Lualhati Bautista desires is a quiet life. She hopes to build a cozy, little house on a lot of hers in Malolos, Bulacan, and, possessing a green thumb, plant flowers and vegetables all around. She doesn’t care about the social whirl. She’s happy enough swimming with her very close friends and going out with them where socializing has nothing to do with work or business. She’s happiest, above all, when she’s surrounded by her brood, composed of Lev and his children Lea, 9, and Lance, 4; Daya and her daughter Aira, 2, and son Eman, 6 months; and Joy and her baby Xyril, 1.

Mahal,” from her book, Alitaptap sa Gabing Madilim

Lualhati Bautista insists there’s not much going on in her life. She’s concerned as ever with women’s rights, with earning a living, and with her novels—Bulaklak sa City Jail, which is based on her movie script of the same title, and Desaparesidos. Her books continue to sell as they are taken up in schools.

For seven months in 2012, she wrote and developed a teleserye, 5 Girls and a Dad for Net 25, which aired from Jan. 23 to Aug. 24. It’s a drama about a single father who, as a taxi operator and driver, fends for his five daughters.

On her free days, Lualhati gets to enjoy reading, watching movies, and being with her brood and with her six grandchildren.

Lualhati, paano ka ginawa? She’s nearing her senior years, yet she’s still full of practical goals and romantic dreams. From where comes her optimism, her control of her life? Read her words. Read her.