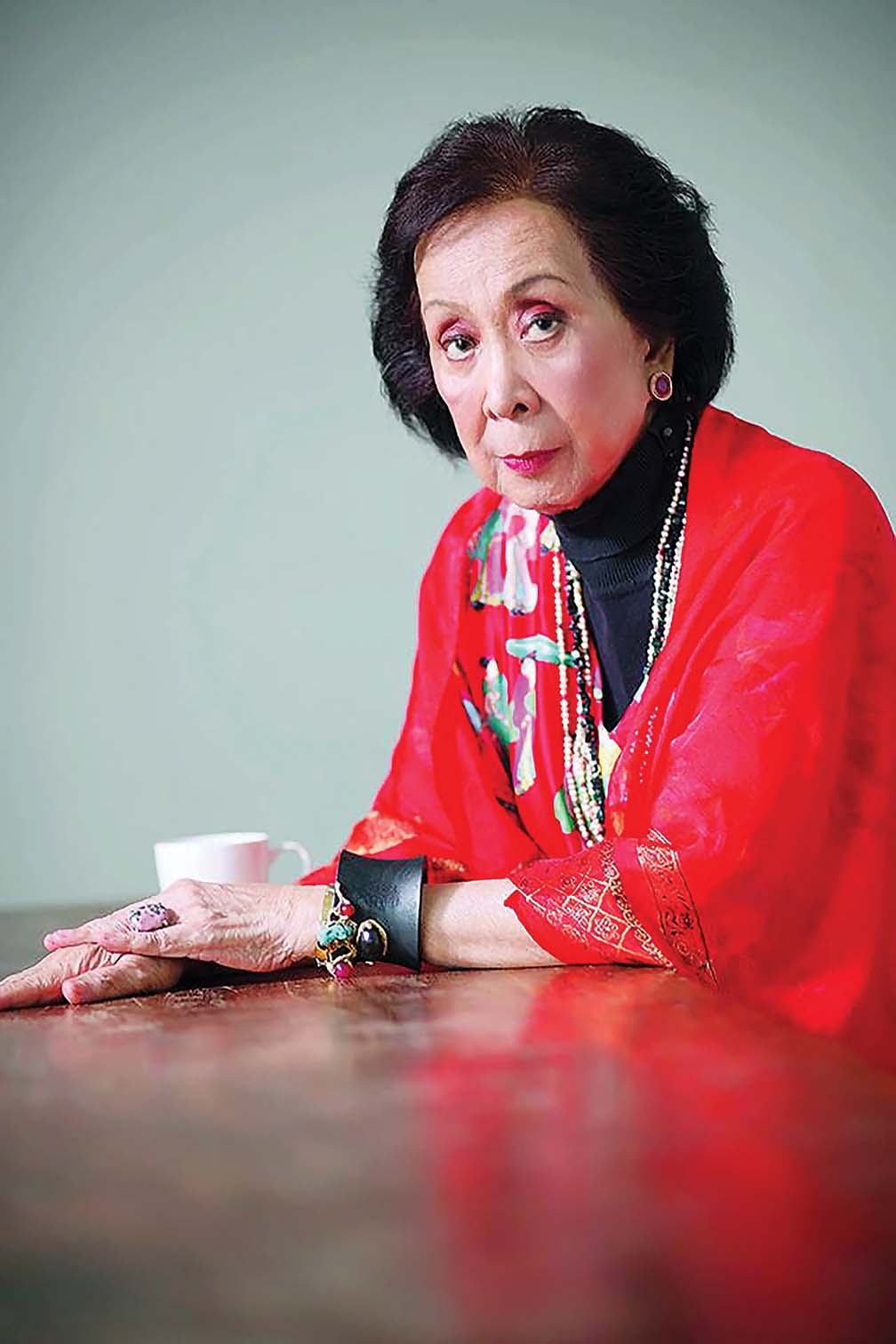

When Carmen Guerrero Nakpil peacefully breathed her last on July 30, 2018, I knew I was witnessing the end of an era of good and insightful writing.

There was a moment of denial when I received the early morning text from her daughter, Gemma, which said, “Mom died at 1:30 this morning.”

I was checking my grandson’s school bag, and obviously the news sank in quite late.

This was one message I couldn’t receive with equanimity.

Before I knew it, my grandson saw his grandfather crying like a baby.

I guess it was my destiny to be drawn to strong and accomplished women, from Cecile Licad to Marilou Diaz-Abaya, and from Gilda Cordero Fernando to Kerima Polotan and Nakpil.

WELL-LIVED

Nakpil must have been my first History teacher that I took very seriously. History, as I learned from classroom teachers, didn’t make any sense (at least to this once young islander).

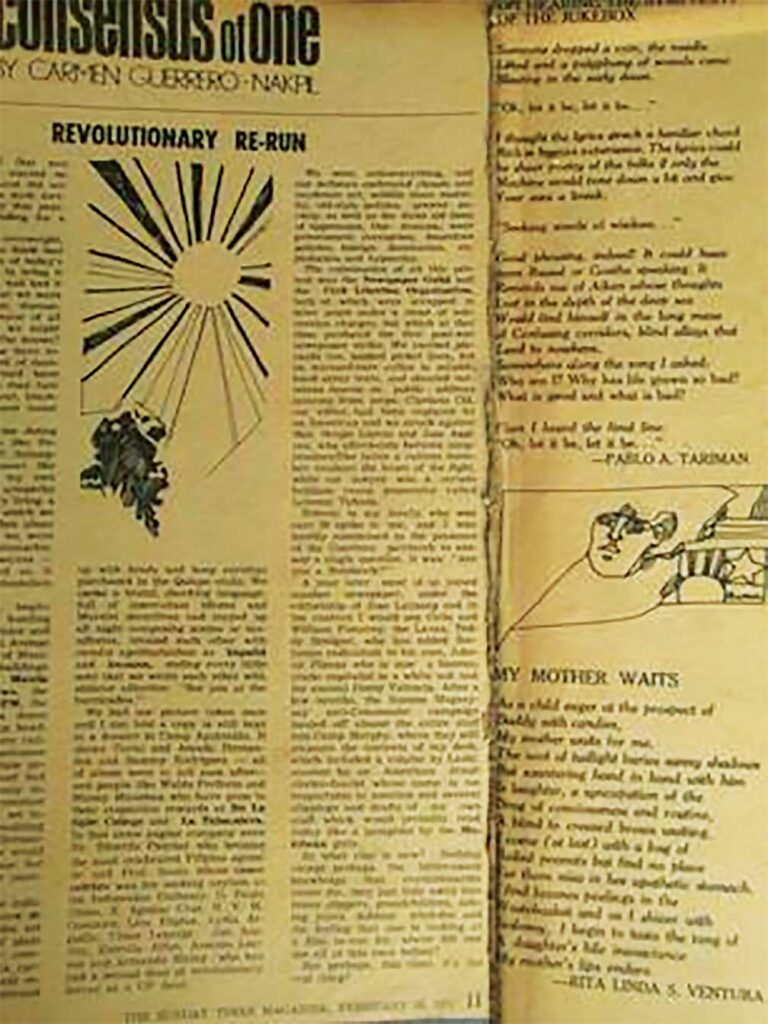

From my early high school days to early college life, I swore by her weekly column, “Consensus of One,” in the Sunday Times Magazine (STM).

On the day, she was about to be cremated at the Heritage Park in Taguig. I vanished thoughts of seeing her for the last time.

I told a poet-friend: “I cannot see her for the last time in that state.”

My friend said, “You won’t see her in that state. She has been cremated and her ashes are in a jar enclosed in a box surrounded by flowers…”

Since I was not sure I could accept her passing with some civility, I decided I would stay home.

I freeze the face of my grandson looking at me crying like an abandoned baby.

Yes, indeed, there is some truth when a wise man wrote, “There is a sacredness in tears. They are not the mark of weakness, but of power. They speak more eloquently than ten thousand tongues. They are the messengers of overwhelming grief, of deep contrition, and of unspeakable love.”

Alone at home, I reflected on the number of times I shared that well-lived life.

MUSIC, WEDNESDAY LUNCHES

I first saw her in the summer of 1971 when I collected my writer’s fee for my first poem published in the Sunday Times Magazine of the Manila Times.

After getting cold cash from the cashier’s office on Florentino Torres Street in Sta. Cruz, Manila, I went to the editorial office just to get a glimpse of Ms. Nakpil.

The typical probinsiyano that I was (and still am), I was content staring at her. After looking for some time, I quietly slipped out like a star-struck fan.

In the ’80s, I discovered that Nakpil loved music, and it was with much delight that I saw her quite often at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP), where I was then working as managing editor of an arts magazine.

A few times we agreed to meet to watch a concert.

I am staring at a book (“Lake Wobegone Days” by Garrison Keillor) that she gave me after watching Rossini’s “Barber of Seville” at University of the Philippines’ Abelardo Hall. It is dated Feb. 1, 1989.

She also attended most of the Licad concerts at CCP, sometimes escorted by columnist Joe Guevara, who would sing, “Mr. Tariman, Talili-Banana” every time he saw me, and Ms. Nakpil would gently tap his hand to stop the joke.

I believe I joined the (Carmen Guerrero Nakpil) CGN Media Group that met every first and last Wednesday of the month just to have a regular glimpse of her and her equally celebrated daughter, Gemma.

Joining that group was providential. Those were the years she was writing her autobiographical trilogy.

I also knew that any of those Wednesday lunches could be my last with her. There was something in the way she looked that said she wanted a graceful exit without the grand tribute and speeches.

LIVING ICON

Born in 1922 to a distinguished Ermita family famous for its painters and poets as well as scientists and doctors, Nakpil was herself a living icon of history.

Her first marriage in 1942 was to an Ateneo graduate named Lt. Ismael Cruz, a grandson of Maria Rizal, sister of José Rizal.

Her second marriage in 1950 was to architect and city planner Angel Nakpil, cousin of composer and patriot Juan Nakpil, son of Gregoria de Jesus, who was formerly married to Andres Bonifacio.

On the Guerrero side, she is the granddaughter of the country’s first licensed pharmacist, Leon Ma. Guerrero, who is the younger brother of painter Lorenzo Guerrero, the mentor to Juan Luna. She is grandniece of Jose Mossesgeld Santiago-Font, the first Filipino opera singer to invade La Scala di Milan in 1932.

Nakpil also happens to be the granddaughter of Gabriel Beato Francisco, a distinguished Tagalog writer, journalist, novelist and playwright.

Referred to as “national treasure” in the field of public history, Nakpil was a good choice when she was named chairperson of the National Historical Commission from 1967 to 1971.

From 1975 to 1985, she served as managing director of the Technology and Livelihood Resource Center.

Nakpil wrote a column for the pre-martial law Manila Times and Manila Chronicle, among other publications.

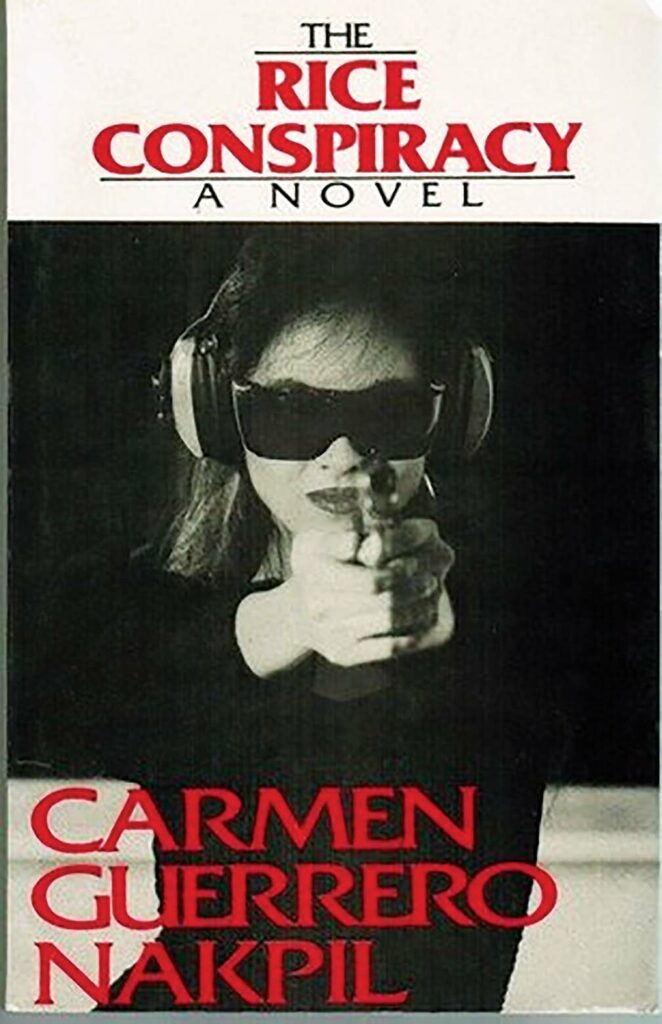

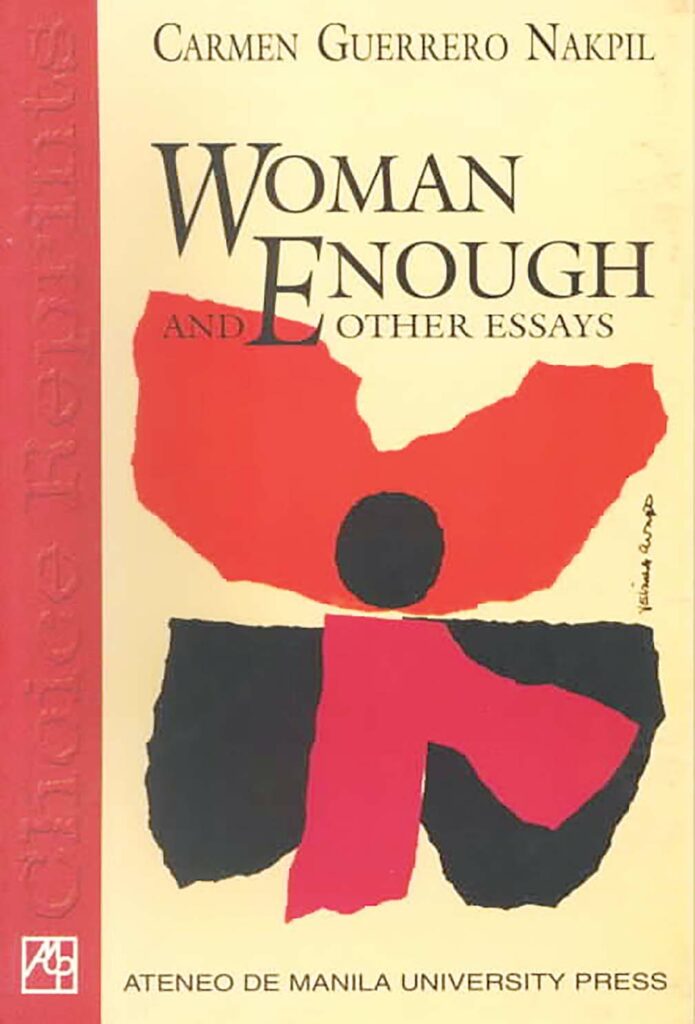

She is author of 10 books on history and related topics. In 1990, she wrote a novel, The Rice Conspiracy.

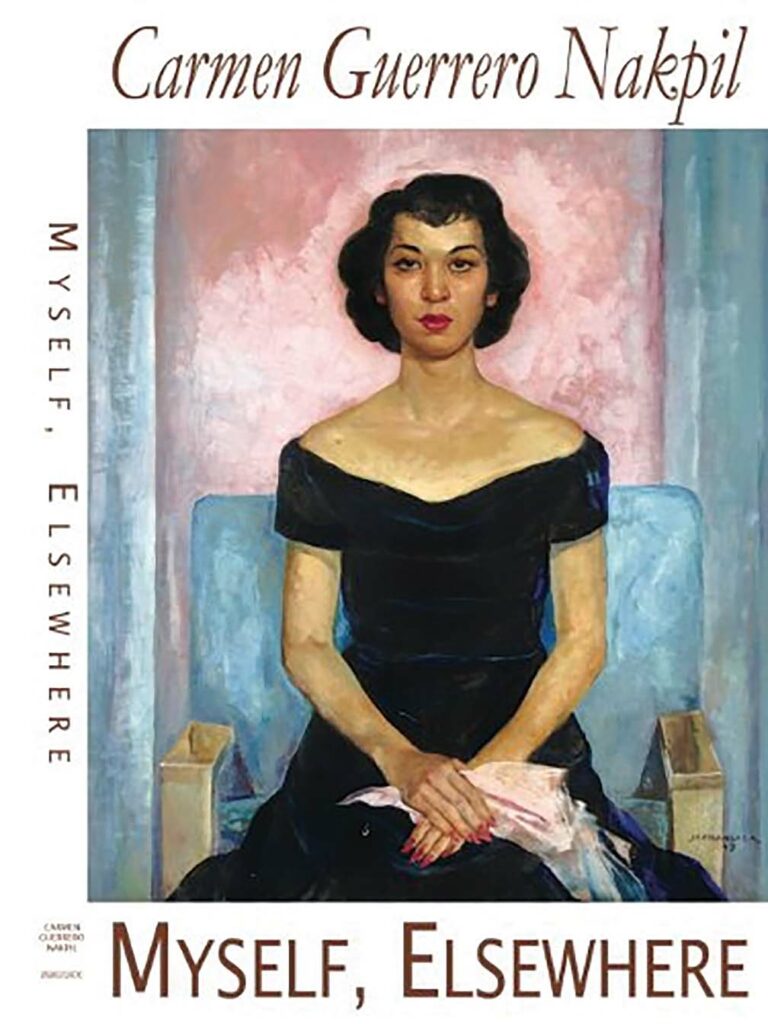

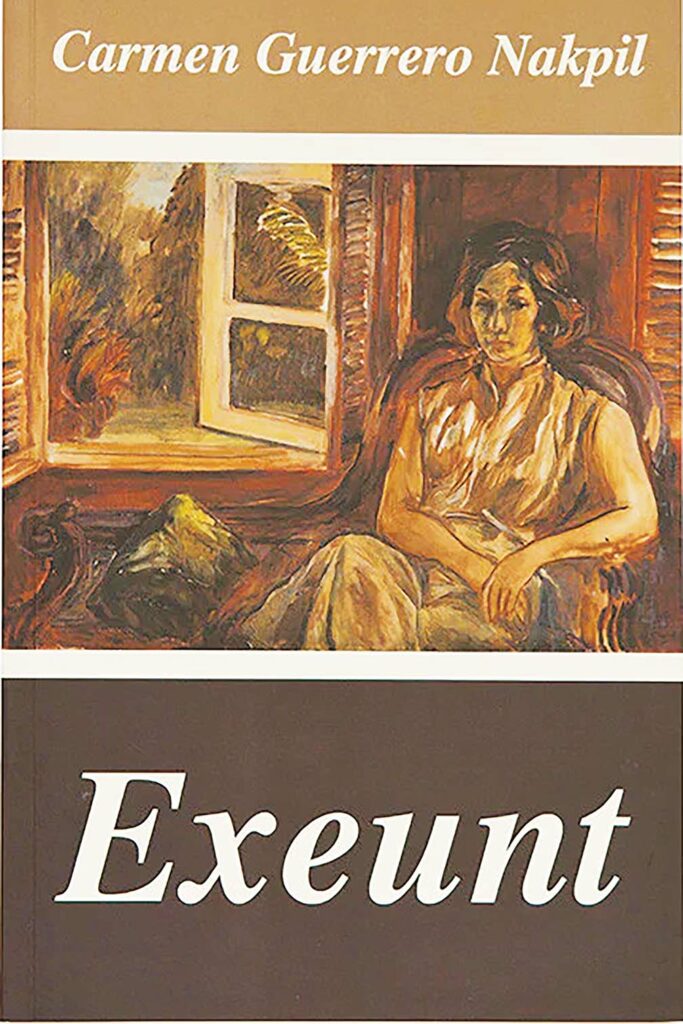

Colorful chapters of 96 years of her life are summed up in her autobiographical trilogy, Myself, Elsewhere (2006), Legends & Adventures (2007), and Exeunt (2009).

HISTORY CHALLENGED

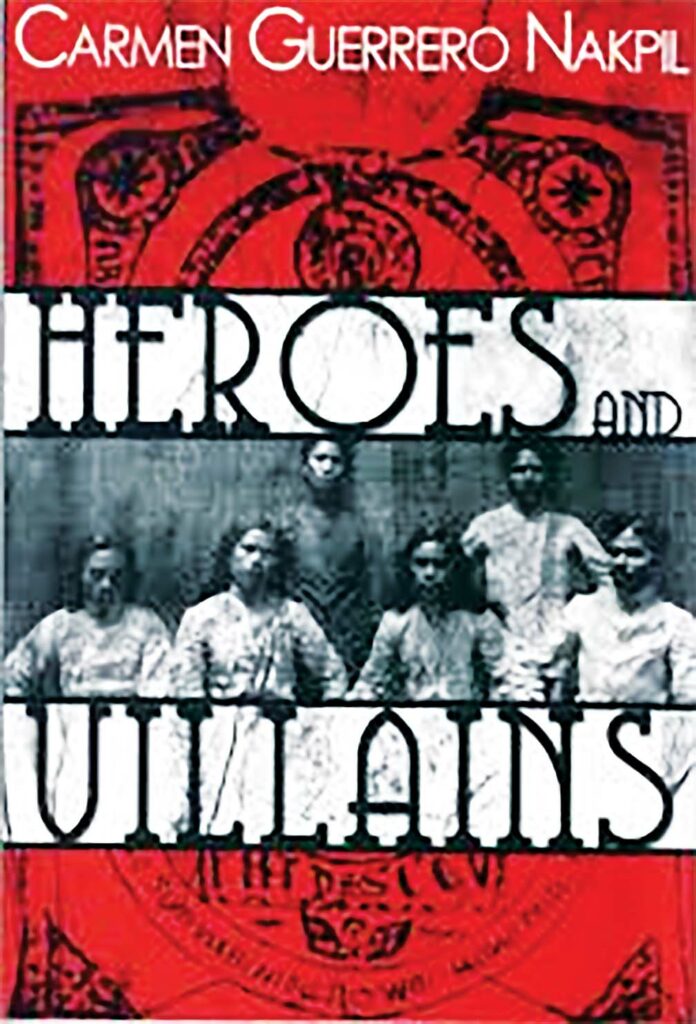

The 17 articles in the book are first-rate essays that enable as to reflect on our past and present with facts that challenge the “official chroniclers.”

Nakpil’s book, Heroes and Villains gives us a ringside view of history totally dissociated from the point of view of the colonizers.

Did Magellan actually discover the Philippines?

Nakpil delivers the cold, hard facts: “It was the people of our archipelago who discovered Magellan and the Europeans in 1521, not the other way around, as most Filipinos were taught by our grade school textbooks.”

The Philippines got its name from Spain’s King Philip II. What was he like and what was his place in history?

Wrote Nakpil: “In his youth, he was described as ‘slender, elegant and good-looking.’ After all, he was the grandson of the smashingly handsome Philip I, a.k.a. Felipe El Hermoso, who was so gorgeous that when he died suddenly at age 28, the besotted Queen, Juana, went out of her mind and was forever called ‘Juana la Loca.’ Historians like to say that she refused to have his cadaver taken from her bedside and kept him there unburied ‘for years.’ A side story to this royal insanity says that when Magellan baptized Humabon’s wife in Cebu in 1521,he gave the ‘Queen of Cebu’ the name ‘Juana’ in honor of the unfortunate grandmother of Philip II, Juana La Loca, a.k.a. in English history as Joanna the Mad. Fortunately, the Cebuanos did not know that little detail of their brief alliance with Magellan, or they might have planned the massacre earlier.”

The secret delight of this book is that history is told in the context of present-day Filipinos still misled by the official chroniclers of history.

After reading the book, you begin to see who are the real heroes of history and those who can be rightfully called the villains.

Wrote the author in the book’s introduction: “I won’t be so mundane as to offer definitions of ‘hero’, ‘heroism,’ ‘villain’ or ‘villainy.’ I believe all heroes define themselves and all villains are defined by the people around them. Some are both heroes and villains to different publics, like the U.S. President William McKinley. Highly regarded for making the U.S. a world power by annexing the Philippines, he is derided by Filipinos for claiming he tried to ‘Christianize and civilize’ a backward people. Filipinos had been Roman Catholics for more than three hundred years, their artists had won medals at world expos in Paris and Madrid and their Spanish-language poetry was anthologized in Europe.”

Further, the book allows us to take a serious look at our mentors (the Spaniards, the Americans and the Japanese) for what they are.

The author cites 333 years of Spanish rule (1565-1898) and points out that at the end of the 15th century, when the European Age of Exploration took off, Spain did not exist as the nation-state that we know now.

She added that what were previously known as the natives of Hispaniola were scattered descendants of the Visigoths, the barbarians at the gates of the dying Roman Empire.

Nakpil pointed out: “For 800 years before Columbus, they had been the subjects of wealthy, sophisticated Arab emirates and Moorish kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula, then a part of the power and the glory of Islamic culture, its splendid palaces, mosques, libraries, centers of learning, arts and sciences. The oppressed, rugged, backward Visigoth Christian natives (the Spanish) longed to drive out the hated Moors (Moros). Propelled by fierce and cunning hatred of this superior culture, they formed the little medieval kingdoms of Castille, Leon, Galicia, and Aragon. But they were dismally poor and unlettered. Queen Isabella’s handwriting was hardly legible, says one historian, and the Reyes Catolicos, the famous couple, Ferdinand and Isabella, were so impoverished they were often on the verge of having to sell the family jewels or melt the silverware to finance an internal war. But hard times toughen people. And the Spaniards were honed by poverty, war, disease, hatred of the Moors, rich Jews, all foreigners and, finally, the Inquisition into a formidable, fighting force.”

For one, the author pointed out, Spain had not had the benefit of the Florentine Renaissance or the wealth of the Ottoman Empire.

She added details of the motherland’s little-known past: “It had a small nobility of peasants, usurers, mercantilists and a huge mass of beggars, vagabonds, bandits and slaves. In Madrid civil servants, captains without companies, soldiers of fortune, adventurers fleeing creditors, all sought passage to the newly charted “Indies” (including Filipinas) hoping to attain, wealth, respectability and a rich wife. (See Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Age of Philip II.) These were the worthies who came to this archipelago to lord it over us.”

Nakpil’s coup de grace: “Our ancestors were not pygmies, the naked savages with frizzy hair, as many of us were carefully taught in our foreign-guided schoolrooms by our brainwashed elders. We were one people, of the Malay race, recognized by India, China, Japan and later Arabia as their ancient chronicles attest, possessors of this land for many centuries. They had come between 200 B.C. and 300 A.D. from the vast mainland of Central Asia, from places like Nepal and Johore, in their own boats for they were excellent seafarers. They lived in organized communities, fiefdoms and villages called barangay (the name for their boats and still that of our smallest municipal unit). They were warriors, farmers, craftsmen, traders, exporters (Mindoro exported cotton to Malacca in the 10th century), investors in Moluccan enterprises. (H. de la Costa, Readings in Philippine History, and W.H. Scott, Barangay.) When Magellan landed in Homonhon in 1521, in the company of his starving, smelly, bearded white crew who had emerged from their tiny creaking, wooden caravelles, they were quickly offered jars of palm wine, welcomed to bamboo palaces and fed roast pork and gravy, rice and coconuts, amid gong music and maidens wearing shiny silk gowns and makeup and attendants wearing heavy gold necklaces, bracelets and anklets. Magellan had to warn his men against showing too much awe of the wealth, the beauty and the generosity of those early Filipinos. It’s important to remember this scene (from Pigafetta, Magellan’s publicist) because that’s where we’re from.”

There is a lot to enjoy in Nakpil’s book and readers will find out why as they go through its 118-page sojourn into history.

It is an enjoyable mirror on which we can reflect our past. Indeed, it should teach us (as the author intended) how we should manage our future.

In 2011, National Artist for Literature F. Sionil José called Nakpil “a sterling, irreplaceable Filipino writer.”

He wrote of her thus: “I have always admired Chitang (Nakpil) the craftsman; her felicitous command of English is equaled perhaps only by Kerima Polotan and Gilda Cordero Fernando.”

TRILOGY

Reading Mrs. Nakpil’s life is by itself a living lesson on history.

In the first part of her trilogy, Myself, Elsewhere, she paints a breath-taking recollection of pre-war Ermita beach where fishing boats deposited and disposed of the day’s catch and where people dropped everything to observe the 6 p.m. oracion when the angelus was prayed.

That pre-war idyll was the exact opposite of her early adult life starting 1942 when she saw Japanese soldiers taking over Ermita. Her brother Leoni became a prisoner of war together with her would-be groom, Ismail Cruz.

At age 20 on August 29, 1942, Nakpil married her prisoner-of-war bridegroom she fondly calls Toto and started living with her in-laws in Gen. Luna St. in Paco, Manila. In that household was her husband’s famous grandmother, Lola Maria Rizal, favorite sister of Jose Rizal.

The marital bliss was short-lived. Less than three years after that marriage, she lost everything in that war: her first husband, her home and all kinds of resources except her parents and her brothers who had become destitute.

She was a widow with two children to raise at age 22.

In Legends & Adventures, the second book in the three-part trilogy, Nakpil focused on her post-World War II life as war widow, reporter, editorial columnist and Marcos official. Here she sums up another life as mother of the country’s first Miss International, Gemma Guererro Cruz and the rise and fall of Marcos, among others. Casually, she tarried on the International Cancer Ball where she danced with Hollywood actor Gregory Peck at the Manila Hilton.

With her last book, Exeunt, Nakpil confronted the inevitable: “I have come to the conclusion that old age is really just a form of slow death. That’s probably why people say that ‘the good die young.’ They die swiftly, in their prime. The other kind, ‘the poor sinners’ like me, hang on, unaware that the series of minute changes, difficulties, disappearances that occur with increasing regularity, a tooth missing, a bone breaking, a sudden ache, a mysterious weakening are really part of the inevitable final dissolution.”

Reviews of her last three autobiographical books were testament to a life well-lived.

Manuel Quezon III described them as “powerful, authentic—a look back at the way people lived, loved, even hated.”

Filmmaker Chito Roño found in the book “all the passion, intrigue and action to make a great movie.”

Peque Gallaga says the memoir does more than show the way we were. “It also captures a state of mind long vanished.”

Adrian Cristobal acknowledged Nakpil’s books had enough materials here for a Philippine version of War and Peace.”

MARCOS, MARTIAL LAW

Nakpil chronicled her life during the first few years of martial law and the year Ferdinand Marcos Sr. ran for the presidency.

She thought her family would be spared from martial law arrests because Marcos was a San Juan neighbor of long-standing and genuinely preferred him to Diosdado Macapagal during the 1965 elections.

In her autobiographical book, Legends and Adventures, Nakpil wrote that the 1965 presidential elections rattled the domestic peace in her San Juan household. Her husband, Angel Nakpil, preferred Macapagal and she preferred Marcos. During that presidential campaign, her husband’s Benz carried Macapagal stickers and her little Renault was “plastered with Marcos’ exuberant promises.”

Years after martial law was declared, Nakpil got it from the former First Lady Imelda Marcos that she was in the list of those about to be arrested but the latter vouched for her and her name was removed from the prominent Martial Law prisoners’ list.

She actually got an advance notice of the imposition of Martial Law from writer Adrian Cristobal who was then head of the Social Security System. A day later, her nephew, Amadis Ma. Guerrero, then writing for Graphic Magazine and Associated Press, was at her doorstep looking for a place to hide, followed by Nick Joaquin, with Pete Lacaba in tow.

Then she remembered her celebrated activist-beauty queen daughter, Gemma Cruz then married to Antonio (Tonypet) Araneta. At that time, the former Miss International was a member of Makibaka, a militant women’s movement that she sensed was more leftist than feminist. As part of her Makibaka work, Gemma helped take care of a day care center for the families of market vendors in San Andres Bukid.

Nakpil inspected Gemma’s boxes in the family library and found them full of anti-Marcos propaganda. She asked her maid to dump those boxes in the nearby creek.

As it turned out, it was Gemma’s turn to be invited by the military. The former Miss International was interrogated for almost a week and later put under city arrest and was told to report regularly at Camp Aguinaldo.

After months in hiding, Gemma’s husband, Tonypet, was also arrested while visiting his family in Forbes Park and incarcerated in Fort Bonifacio.

At that time, foremost in Nakpil’s disposition was her mother’s instinct. She couldn’t imagine her daughter in jail so did her son-in-law. Swallowing her writer’s pride, Nakpil personally saw Marcos and implored that her son-in-law be released.

The family then decided it was better if they leave the country. Gemma flew to Canada and ended up in Mexico with her daughter Fatimah while her son, Leon (then only three years old), was left in his father’s care in Manila.

In Nakpil’s own words, the family was shattered and the marriage never recovered.

Nakpil described the effects of Martial Law on her family: “On our family, it caused pivotal, grievous, collateral damage. It wasn’t only the truncation of my journalistic work, but also the hyper-real destruction of a family, and great personal tribulations and sacrifices.”

For sparing her daughter and son-in-law from prolonged harm of martial law, Nakpil couldn’t say “No” to a Marcos job offer.

She was aware people were asking questions as to why she worked for the Marcoses.

Nakpil rued: “My reply would usually be a forthright soliloquy. It isn’t really, just that I compromised myself by pleading for clemency and freedom for my activist daughter and son-in-law, or that I like the projects in the Technology Resource center where I work, but also at bottom, because Marcos was doing important things that I swear by… I found comfort in reminding myself that I was a dutiful bureaucrat, well-intentioned, but destined by circumstance to be caught in the maelstrom.”

GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA

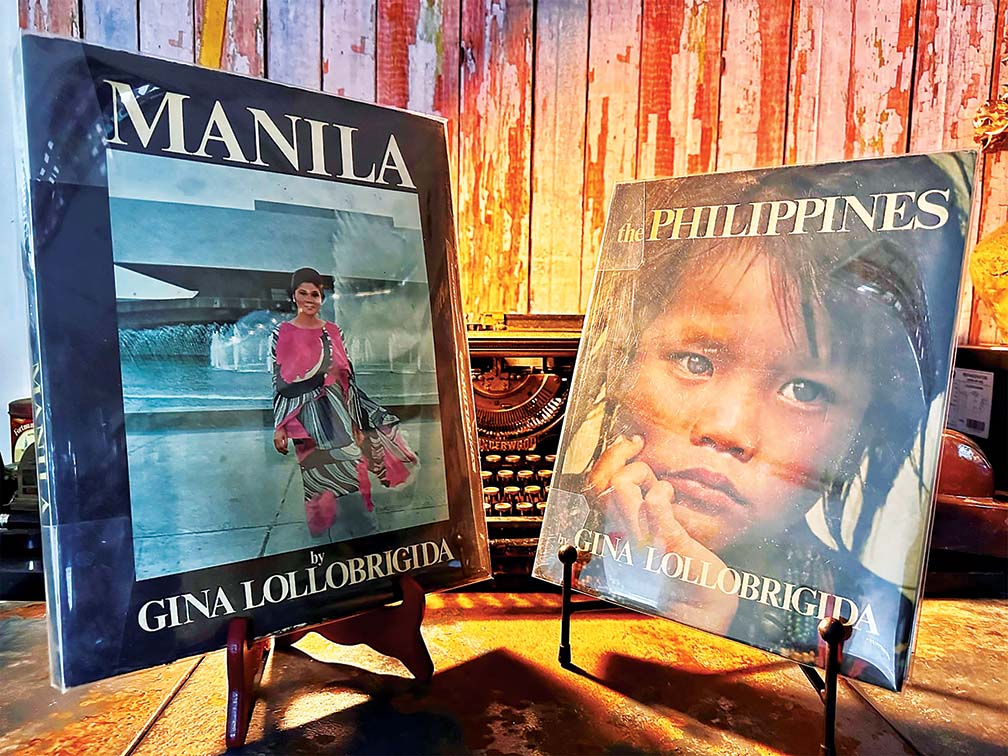

In her memoirs was an episode where she had a running cultural battle with Italy’s sex symbol, Gina Lollobrigida.

In this episode in Manila in 1975, Nakpil was assigned to do the book introduction with Lollobrigida supplying the photos.

When the Hollywood star turned photojournalist arrived in Manila in the mid-70s, she got VIP treatment and was escorted by good-looking soldiers in her forays in Mindanao.

In her book, Legends & Adventures, Nakpil wrote that the international sex symbol was able to wangle a “whale of a contract befitting her stature as the ‘sexiest woman alive.’”

The book contract was between the Italian sex symbol and the PNB represented by its then president Panfilo Domingo.

Nakpil recounted her role was to provide the text and then travel to Italy to supervise the printing in Florence.

Recalled Nakpil on her first project meeting with Lollobrigida: “She had clearly seen better days, but she was still magnificently attractive, with huge, long-lashed eyes, a head of dark curls, the famous bosom and small waist.”

The writer noted the Filipino men present in the meeting were on the verge of a major crush.

As Nakpil showed her the text for the volumes on the Philippines and Manila, the Italian Hollywood star complained: the text did not seem to match her photos.

The writer gave the movie star a piece of her mind. “Your photos are all about a Stone Age tribe in the jungles of Mindanao, about half a dozen aborigines, and this book is supposed to be about 45 million Filipinos who don’t live in trees.”

The actress said her book has a different market and that Europeans are not interested in Filipinos living in high-rise buildings and driving European cars on superhighways.

Writer insisted the book has to be truthfully told that Filipinos don’t live in caves.

Nakpil couldn’t hide her irritation on the way La Lollo wanted the book to look like. “My irritation was aggravated by the dark freckles on Gina’s décolletage, the four sets of eyelashes she wore above and under each eye, and the wormy varicose veins on her legs visible only when she raised her long skirts. I refused to change a word of my text, and it was not so much feminine envy as patriotic indignation. I was the librettist, the one who would supply the words for the operatic arias of her art photographs and that made us natural enemies. She had the imperiousness and arrogance of a Hollywood film star who expected adulation and subservience with one blink of her fantastic eyes and a pushy delivery that antagonized me with its comical Italian accent. I annoyed her because I remained unimpressed and was critical and argumentative, suspicious of her manipulative strategies.”

The writer and the celebrity photographer fought every time they met to discuss the project in the actor’s Bel Air abode.

Indeed, the stage was set for a cultural battle for the writer and the actor commencing in Manila and ending in Florence where the books would have its final printing.

Nakpil’s concern: why was there too many photos of the Tasadays than for the ordinary Filipinos living outside the forest?

Observed Nakpil: “There was preponderance of people who were naked, with not even a G-string or a loincloth between them and the camera lens.”

In the Florence printing press, the Italian press workers suffered from cultural shock. They couldn’t believe Nakpil was a Filipino and insisted that the writer must have Spanish origin and insisting that real Filipinos have heights the equivalent of pygmies. The writer lost her patience and yelled at the Italian printers: “Who are you calling a pygmy?” looking down her nose. She knew it that the bias came from Lollobrigida’s photos of the Tasadays.

Meanwhile, the books on Manila and the Philippines carried the author’s unexpurgated text which dealt with the history, geography, economy and the character of the diverse Philippine population.

Lollobrigida got around to writing her own epilogue at the rear of the book.

Despite the lack of official approval, 60,000 copies of the books were copyrighted at Liechtenstein and printed by Zincografia Fiorentina in Italy in 1976.

Project overseer Marita Manuel also disapproved rushes for the proposed film project that would go with the books.

PNB withheld payment for Lollobrigida. PNB president Domingo argued that the books were not representative of the Philippines as stipulated in the contract.

As a counter action, Lollobrigida sued Mrs. Marcos who approved the book contract.

Domingo negotiated during the court hearing and actress only got one tenth ($400,000) of the $4 million contract.

In Nakpil’s account, books were delivered to Malacanang but never distributed.

Domingo kept 10 copies for his friends. Nakpil got a copy of her version The Philippines with front and back covers of the T’boli maiden in her hand-woven, beaded costume and a copy of Manila with former First Lady Imelda Marcos at the CCP entrance.

THE LAST YEARS

It was providential to witness her last few years.

She was appreciative of the respect and recognition but she is at once embarrassed by dinner speeches summing up what she was in the fields of Philippine history and journalism.

Nakpil liked to call herself the condo-dweller in First World Makati.

She was all alone most of the time waiting for what she said fellow Catholics loved to invoke as “the hour of our death.”

In this last phase of her life, Mrs. Nakpil admitted she has finally understood many things, both small and huge, fripperies and profundities.

She reflected: “We Filipinos draw our endless patience, our good nature and our trust in God’s master plan from a simple unshakable faith.”

Quoting lines from St. Theresa of Avila, she wrote: “Nada te turbe. Nada te espante. Let nothing disturb or frighten you. Everything passes. God never changes. Solo dios Basta. God alone suffices. No longer restless or fractured, rid at last of all strange gods, this very old heart withdraws into peace.”