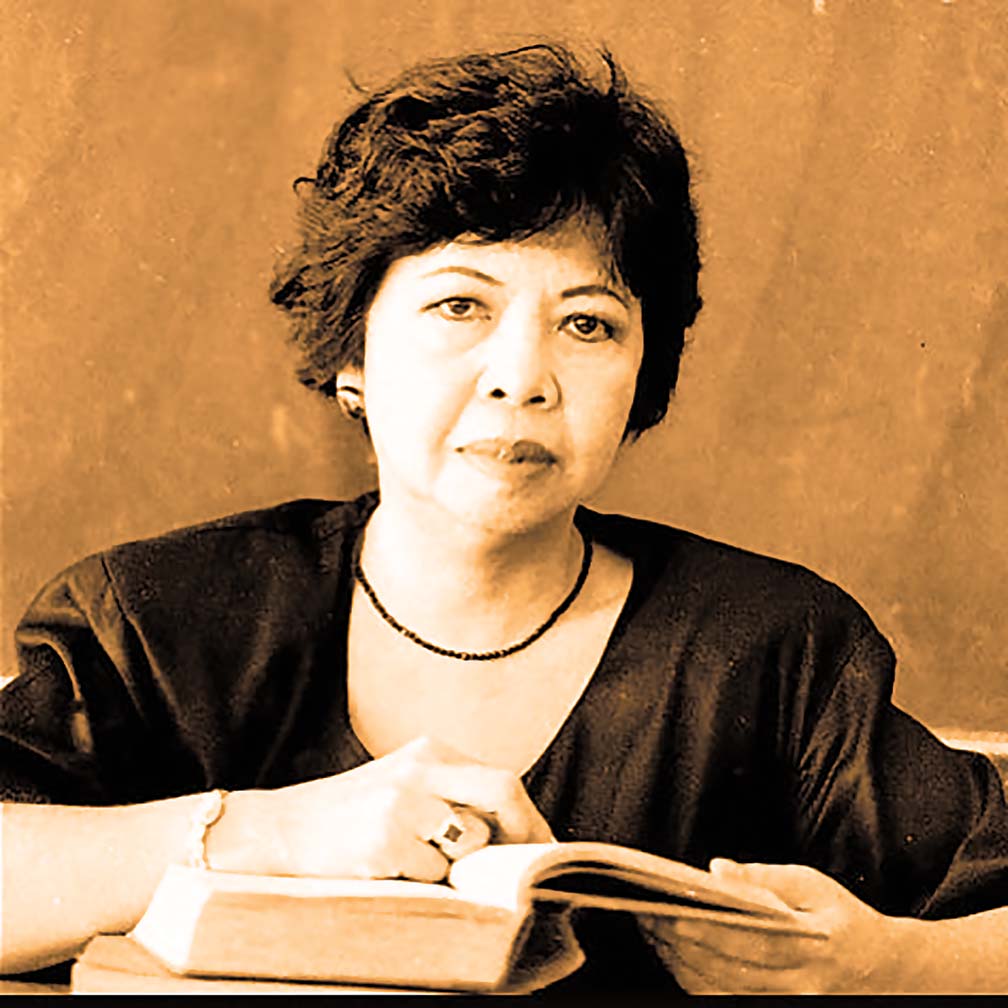

The late great Ophelia Alcantara Dimalanta became one of the Philippines’ major poets “regardless of gender” but her first love was music, and she was trained to be a concert artist.

Why, she could have been another Van Cliburn (“better,” the nationalist music lover would snicker) or a Cecile Licad. But, after graduating from high school, she was forced to choose between the University of the Philippines Conservatory of Music and Journalism at the University of Santo Tomas.

She chose the latter. From journalism she gravitated to poetry and as they say, the loss to the concert stage became the gain of belle lettres.

Classical music and children’s lit became her early influences. In an interview with Sr. Bernadette Racadio (who was researching for a Ph.D. dissertation on Dimalanta’s poetry), the poet recalled that her mother loved to read romances and at bedtime would tell her children about these stories.

“Arts and sciences” would best describe the Alcantara parents. Ophelia’s father was a brilliant mathematician, and was one of the founders of Mapua Institute of Technology. He was also a respected professor of engineering who wrote textbooks on the subjects he taught.

In the bionote on the poet, which was published in the anthology edited by (National Artist) Gemino Abad, A Native Clearing, she recalled reading nursery rhymes, Grimm’s fairy tales and romances in between dolls and climbing guava and macopa trees: “I would be for hours in our huge verandah, gorging on all kinds of books. At ten I was already reading Dumas and Hugo; by the time I was in high school, I was far ahead of my classmates, even teacher, in the classics.”

She was also into music, and her mother hired a teacher to give her private piano lessons. And at the age of seven, little Ophie (a nickname which stuck to her until adulthood) was already playing the piano. At 10, she was into the masters Beethoven, Mozart, and Tchaikovsky.

Then came the fateful decision to take up journalism at UST.

Our heroine was born on June 16, 1932 in Navotas when the town was still a part of Rizal province (it is now a city and part of Metro Manila). She was already writing verses before she turned 10.

POETRY & TEACHING

At the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Ophelia was the literary editor of the Varsitarian. She wrote a column on poetry, and had an early poem (“Brown Fervor”) included in poet Manuel Viray’s Honor Roll of the Manila Chronicle.

She graduated at the age of 19 and immediately got married. She already had a baby when she returned to the university a year later for her M.A. in Literature (and later a Ph.D.).

At 20, she was asked to teach Short Story Writing and advance courses in literature. Her students were almost her age.

“I had to buy books and read, read read— my real education began then, not during my college years. I finished M.A. and Ph.D. keeping house for a small family, writing poetry, and teaching all at the same time,” Ophelia recounted.

To top it all, the by now Mrs. Dimalanta came out with a doctoral study of Palanca Prize-winning poetry in English from 1963-1973 (Letran College, 1976).

Ophelia’s priority was always poetry. She was also a prolific writer, writing prize-winning fiction and criticism (along with a play about San Lorenzo Ruiz).

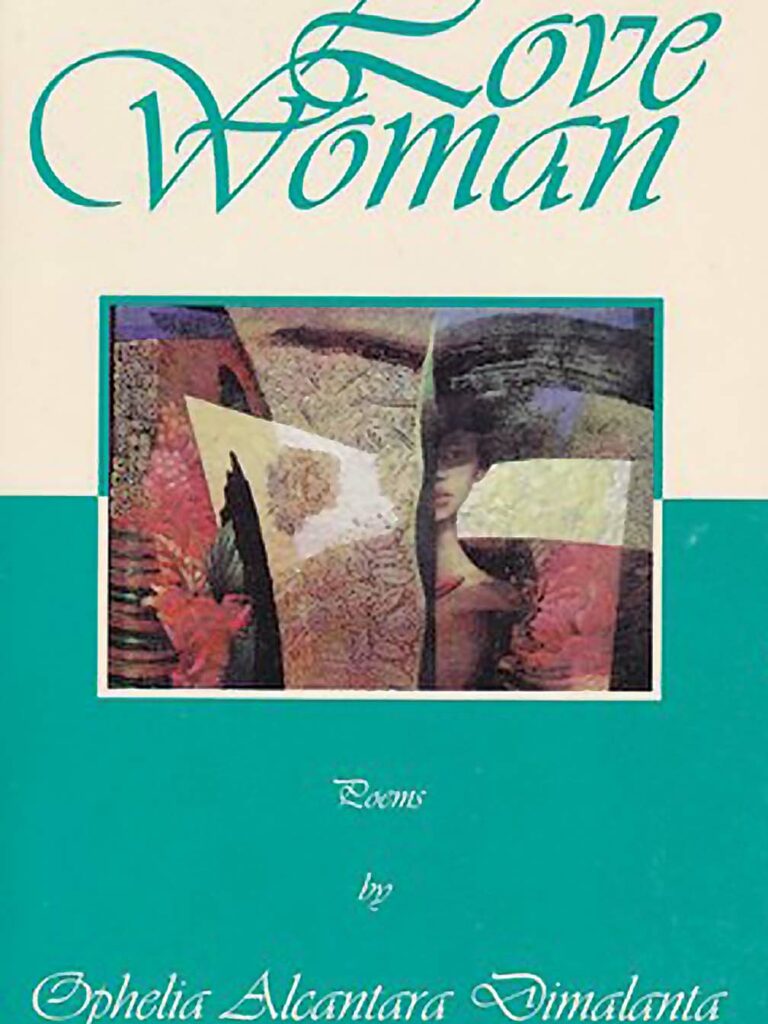

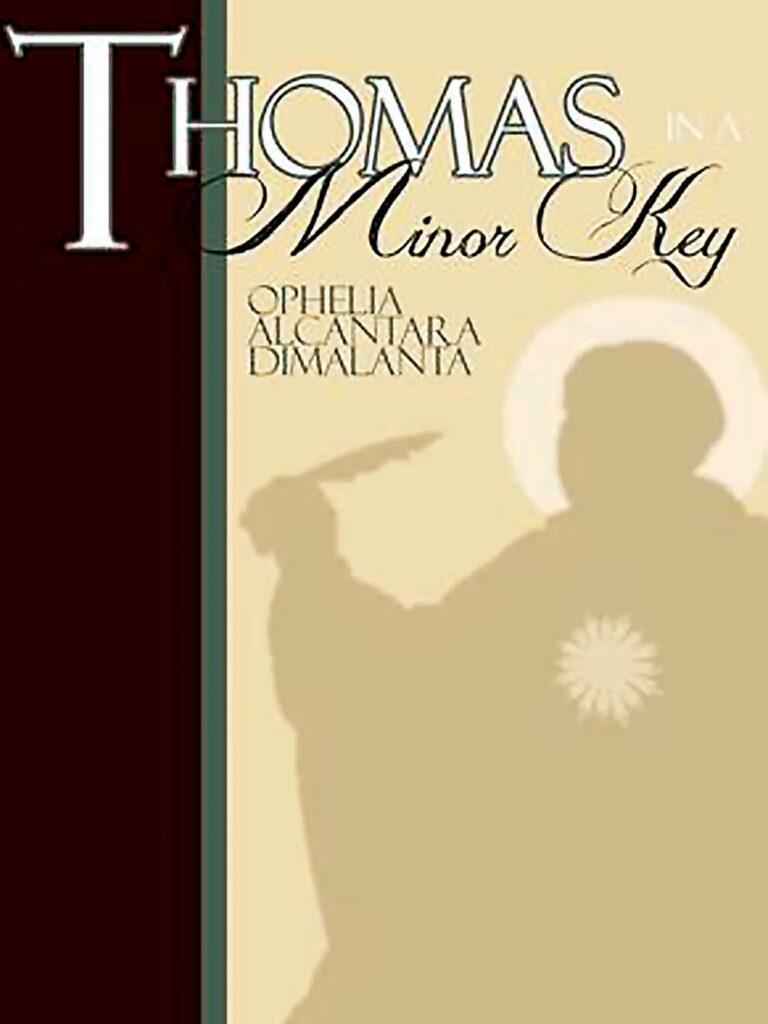

She published seven volumes of poetry: Montage (UST Publications, 1974); The Time Factor and Other Poems (1983, Interpress Publishing House); Flowing On (UST Press, 1988); Lady Polyster (1995); Love Woman (1998); Passional (2002); and The Ophelia Alcantara Dimalanta Reader, Volume 1, Poetry (2005).

“I never stop being a poet, even while I am not writing poetry,” she declared during the interview with Sr. Bernadette Racadio. My poetry satisfies deeper needs, offers more lasting fulfillment.”

In the 1950s her favorite poet was TS Eliot, and by the 1960s he was succeeded in her affections by Wallace Stevens. With the 1970s came a phalanx of favorite poets: Sexton, Levertov, Merwin, Roethke, Berryman and Plath.

Exclaimed Dimalanta: Frankly, of the six only two names are familiar to me—Roethke and Plath. And four were suicide cases! “…but I love life…Poetry is always a celebration of life. Pessimism in poetry is healthy. It proves a poet’s potential for pain-within and around himself, in all contortions of living. It is an expression of the presence of a life-drive, a sense of life-validity, an awareness of the vastness of human potential. My pessimism is never despair, weltschmerz, angst.”

The New Criticism exerted a strong influence over her.

“The New Criticism syndrome was part of my literary evolution,” she declared, adding: “It should be with all writers who have been at one time or another conscious about getting their work done right—that is, according to certain widely accepted standards and norms. It is the school which has formulated more specific, definitive literary theories which a beginning writer could fall back on. But one should not stop there. I have not. I believe that in the importance of good form but form is only the visible part of content. It must grow around a cerebral nucleus. Yes, I know when I have written a good poem. It is virtually unimproveable. And I like the sound of it. I go by the ear and I think I have a good ear.”

CONFRONTING THE POETRY

Three distinguished critics, among many, have written probing essays analyzing and explaining the poetry of Ophelia Alcantara Dimalanta: Noted novelist, short story writer, and essayist Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo, director of the UST Center for Creative Writing; poet, translator, and editor Ralph Semino Galan, assistant director of the UST Center for Creative Writing and Literary Studies; and Joselito Zulueta, a professor of literature and journalism, essayist and journalist.

In her 1996 essay, Pantoja-Hidalgo disarmingly admits that when she first encountered the poems of Dimalanta “I did not quite understand them.” She was fresh out of convent school, wide-eyed, and in the midst of many young men who were budding poets and “Ophelia was already Ophelia, high priestess of their enchanted world, muse and mistress of their hearts.” It was only much later, a grown woman and a published writer, when she returned to the poems, that she really appreciated them, and was “astonished and delighted.”

Pantoja-Hidalgo focuses on Lady Polyester, Dimalanta’s third book which was published three years before the essay appeared in the The Evening Paper in 1996. The critic celebrates the poet as a champion of womanhood, of being a woman even before “women empowerment” became a battle cry.

“In these pages is woman, followed through here many passages,” the essayist declares. “Here, Ophelia takes the mundane, the urbane, the precocious, the pretty, the banal, the witty, the bright and the wild. She examines them, mourns them, enables us to remember, and to retrieve. Thus, the experience of reading these lines is like walking with the poet down familiar paths, or taking tea with her in her quiet, lamplit rooms, and one says to oneself…Why, of course, it was like that. I remember…”

In vivid images, Dimalanta writes the experiences of a woman: pregnancy, childbirth, motherhood and making love.

The pains of pregnancy are forgotten in a mood of triumph: …o so overpowering/ Total, this victory/ this feat. This mystery of likeness, of desire/ Impressed upon this given flesh…) On childbirth: There will be no sleep, No twilight calm, no pain./ No syllables but pure primal/ Rhytmic knowing, an urgent/ Forward flow, a powerful arched/ Wave, love rhythm, leaves/ Opening, opening).

Motherhood brings joy as well as exasperation: …children are the tricky monster we love to cuddle in our arms/ one moment and in the next/ consign into dusky corners/ of our sunharsh lives…

For lovemaking, the poetess conjures up powerful images which once scandalized the Dominican fathers of the university: …out into the lush forests/ of a wildly pulsing vagabond heartland lingers playfully/ along the corner of her smile/ secretly sinks, swoons solely/ sovereignty into one/ pungent orange peel sunset/ melting right into a soft dark apricot shade/ into a swirl of naiads/ carousing in her night’s surreptitious hills/ whirling, wanton…”

But one of the children – gasp – catches the couple in bed. The spell is broken, and the verses become more rueful, ironic, similes: (lovers are) more like gaming children and children less like gnarled impatient lovers.

WOMANPOWER, WOMAN ANGST

A gallery of women parade through the verses, from prominent to unknown, amidst a welter of images, metaphors and emotion. The protagonist in “Montage” is a housewife in the throes of dreamland; in “Nara” she is a harassed tourist. The poet bids goodbye to a beloved sister, Amelia, who has passed on. There is a lonely teacher in the poem “Death of Little Boys” and – unexpectedly – a madwoman in “Melancholia.”

Dimalanta also pays tribute to her “braver sisters” like Winnie Mandela of South Africa, (whose good name was later tarnished); Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan (later assassinated, a victim of her country’s violent politics); along with two women whose names are unfamiliar today – Laila Abou Saif, and Sisulu.

In the essay published in The Evening Paper, Pantoja-Hidalgo writes: “And there are the many other faces, other images, haunting presences, beguiling, disturbing. There is woman trapped by “unlove,” by conventions, by creeping old age and death,” and by daily life. And the essayist adds: “There is also woman escaping, enigmatic, elusive never quite there, not even in her diary, which lies there/ for all the world to see/ with all the dishonesty/ of moonrises and cellardoors to assure and reassure those who need assurance and reassurance, but which really reveals nothing (you do not expect me all there/ i pin a rose down/ the next day i wither/ the other half is a pain/ i hide at the pit of my stomach/ i keep diaries nonetheless with all the gaps and walls/ to get lost and alone in…”

MELANCHOLIA

At the heart of all Dimalanta’s poems on love, the critic opines, is a melancholy that makes the poems truly poignant. “And this melancholy lies behind the dry ‘Hack away, love,’ with which she addresses her lover in ‘Love Circa Today’; behind the sadness in (the book) The Time Factor (‘You and I meet, at the wrong time/ Giants both standing above time/ Playing for time, loving against/ Time…”

In the poem “One of the Condemned,” however, amidst all the melancholy, we are given a glimmer of light: “…one of the condemned rooms/ of my heart/ has been granted/ a reprieve/ tiny windows jacked open/ to allow a booster of sun and air…)

The essayist’s favorite is the poem “A Kind of Burning” because it is such a truthful portrait of how finally lonely love is…” And the narrator realizes that she and her man are not just lovers but partners. They have been all the hapless/ lovers in the wayward world/ in almost all kinds of ways/ except we never really meet/ but for this kind of burning.

It turns out that “A Kind of Burning” is also a campus favorite at UST and that it has been acted out by students on stage during the 1990s. And not just in UST, for over at Far Easter University actor Nick Agudo used to read the poem during stage performances.

WOMAN TRIUMPHANT

In the Dimalanta poem “Woman on the Podium, woman casts aside her anxieties and finally emerges triumphant: “Man’s scepter, real or imagined/ Cannot turn the flowing tide/ of her course, trouble the beaten path/ of her flights… One power finally uncaged/ Unplumed stalking, pursuing/ With giant upstretched wings/ Buffling the wind from perch to perch.”

The essayist Ralph Galan focuses on selected poems and volumes from The Ophelia Alcantara Reader, her last published book of poetry. Galan cites What Poetry Does Not Say to reiterate Dimalanta’s belief that poetry should be indirect, no doubt what readers would call “obscure,” or non-expression: “For poetry never says/ it unsays. To say/ is to confine, contain/ to unsay explore the/ vaguely all-hovering/ Presence of the unseen/ deliberately left out…”

Well, the theme is often woman to woman. So can the iconic Princess Diana, whose son Prince Harry has been in the news lately, be far behind? “this final private fling/ this binge of anonymity/ this silken intimacy/ white heat of pain’s/ intensest peaking/ caught raw shorn of royal trappings/ one instant dredging/ of the body’s last reserves/ from those hurt places of the past/ in one last heightened rewind/ in a tight desperate grip of present/ the heart’s leap/ out of its crook/ into blazing. bracing space.”

The poetess has her travel or “transit” poems, the critic indicates. Once she travelled to Greece with an unidentified “you,” and took a shot of the Parthenon. The result was not very good but Dimalanta managed to transform this into poetry: “Not quite worthless/ shots, really/ See there? Excavate deeper/ into the stony sites/ of the receiving mind…// the Parthenon and you// You and the Parthenon/ Subject-Object/ One repressed the other/ played up alternately both// Contemplator and text/ Singer and song/ Separate and One.//”

WOMEN WARRIORS

For the Philippine Centennial, our poetess wrote tributes to six women associated with the Revolution of 1896: Teodora Alonso, the mother of Rizal; Josephine Bracken, “Pepe’s girl friend who became his wife two hours before his execution;” Gregoria de Jesus, wife of Bonifacio; Tandang Sora, who fed and sheltered the revolutionaries; and two women warriors from the Visayas—Patrocinio Gamboa y Villareal and Teresa Magbanua.

“The six poems are quite interesting as sociopolitical commentaries,” says Galan. “They provide us with possible portraits of these women warriors, heroines whose contribution to the Revolution have often been ignored or effaced by the patriarchal chronicles of history. Taken in this context, the six poems can be considered as alternative versions of certain historical events, a herstory of the Revolution, ecriture feminine counteracting phallogocentric writing.”.

Here is the poem inspired by Gregoria “Oryang” de Jesus, “beloved comrade-in-arms”; “Certainly soon, God would will/ to have this woman voice/take a leap into the elements/ coming out naked in its wounding/ under a shower of blazing meteors/ to claim despite the onus/ of here sex and the curse of her time/ what godfully is hers alone.//”

The essayist describes Dimalanta’s fifth volume of poetry (Love Woman) as focusing “on love in all its multifarious guises and disguises: romantic love, erotic love, love for the poor and the disenfranchised, love for dearly departed writer-friends Bienvenido Santos and Edilberto Tiempo, the love of words and the wonderful worlds they create, the love of music, wanderlust, the love of country, love for her ‘gentle/loving, long chafing brood’.”

And he concludes: “Dimalanta’s poetic voices is sui generis (unique, one of a kind). No other poet, nor poetess for that matter, composes poetry the way she does.”

The essayist-journalist Lito Zulueta knew Ophelia Dimalanta well, along with her poetry, of course. He was a former student of the celebrated poet, later a colleague and friend. He recalls that during the 1960s and 1970s she “shocked the Catholic establishment with such erotic lines as ‘for chrisake, hold your tongue and let me come (an updating of Donne’s famous lines) and ‘Hack away, love’.”

Dimalanta had her admirers as well as detractors. “Throughout her poetic career, Dimalanta has been accused of a lot of things,” wrote Zulueta in 2004, just as her fourth volume (Lady Polyester) was about to be published. “In the ‘70s, Jolico Cuadra, a former poet, lauded her technical virtuosity but wandered cynically whether she really knew anything about life (for someone reared in the stultifying environment of UST and had chosen to stay there as a teacher, he pointed out, she could not have any possible appreciation of the world outside of the campus). The feminists have found her either uninvolved or politically incorrect. All in all, her critics have charged her with not confronting life enough, perhaps even falsifying it.”

It seemed that Dimalanta had insulated herself from the world, Zulueta speculated at the time, for she was totally devoted to her family, academic life and writing. “But it is wrong to say that she has removed herself from the vicissitudes of life,” Zulueta asserted. “We who are her former students know of her private and professional travails.”

Her poetic career was marked by what she described as “push and pull”—the push toward the ivory tower, and the pull toward the garbage dump. The latter image could be considered literal because in 1984 the poetess wrote about Smokey Mountain as a symbol of our poverty, “of burnt out dreams…” And the dictator, she said in another poem, created “scenarios with a flick of his scheming finger.”

STRENGTH IN POLYESTER

For Zulueta, the quintessential Dimalanta poem would be “To Lady Polyester” (see TO LADY POLYESTER), earlier published in The Time Factor and reprinted in the fifth volume. “The Images are concrete, the meanings rich and ineffable,” the critic raved. “There is the hint of physical violence and even sexual assault in the subtle images of silk tearing badly at the slightly ‘Brush with the sun and wind and rain.// Curl, fray at the edges/ Under mere finger pressure’. But the controlling logic is the strength of experience, the fortifying lessons of life, the revivifying brush with reality, of awakening.”

In August 2004, the Alcantara-Dimalanta ancestral home in Navotas City was destroyed by fire which raged for two hours. The poetess and her family lost everything: souvenirs of her many trips abroad, personal and professional mementos, books collected through the years, and all her clothes.

Not only that; all the family photos were lost in the blaze. “Yes, all the family photos were destroyed in the fire,” the poet’s son, Al Dimalanta, confirmed to me recently.

“Out of the tragedy have emerged a number of powerful poems that should provide another impetus for lovers of poetry to read her..” shared Zulueta.

Dimalanta died suddenly at her home in Navotas on November 4, 2010, at the age of 78, another major artist bypassed during her lifetime by the “influencers” (to use a currently fashionable word) behind the National Artist Awards. And yet lesser… never mind, I’m sounding like a broken record.

With or without the posthumous National Artist Award, the poetry of Ophelia Alcantara Dimalanta will live on, read and appreciated by those who love good to great poetry. One of her former students, National Artist Cirilo Bautista, no less, hailed her as then “not only our foremost woman poet but also one of the best poets writing now, regardless of gender.”