Very little is known about the first Philippine Press Council, whose job was to assure the public of the journalism community’s commitment to professional and ethical excellence, and that any violation thereof would be dealt with—internally, and without involving expensive, oppressive and liberty-depriving court suits. Let me share a few notes about this first Council, the post-martial law efforts to revive it, the Press Council I had the chance to head briefly nearly 20 years ago, and the current movement to set up media self-regulatory mechanisms around the country.

On July 14, 1965, the first Philippine Press Council elected its members. The body was created by Republic Act No. 4363 as “a private agency of newspapermen, whose function shall be to promulgate a Code of Ethics for them and the Philippine press, investigate violations thereof, and censure any newspaperman or newspaper guilty of any violation of the said Code.”

By its provisions, RA No. 4363 further stipulated the process for filing a libel case against a person or persons who “shall publish, exhibit, or cause the publication or exhibition of any defamation in writing or by similar means, shall be responsible for the same.”

Approved on June 19, 1965, during the administration of President Diosdado Macapagal, Section 3 of RA 4363 stated that RA 4363 shall take effect upon the organization of a Philippine Press Council, with members duly elected and proclaimed by the President of the Philippines.

1965: PROCLAMATION 422

On July 22, 1965, Pres. Macapagal signed Proclamation no. 422, “declaring the organization and election of the members of the Philippine Press Council pursuant to Republic Act No. 4363.”

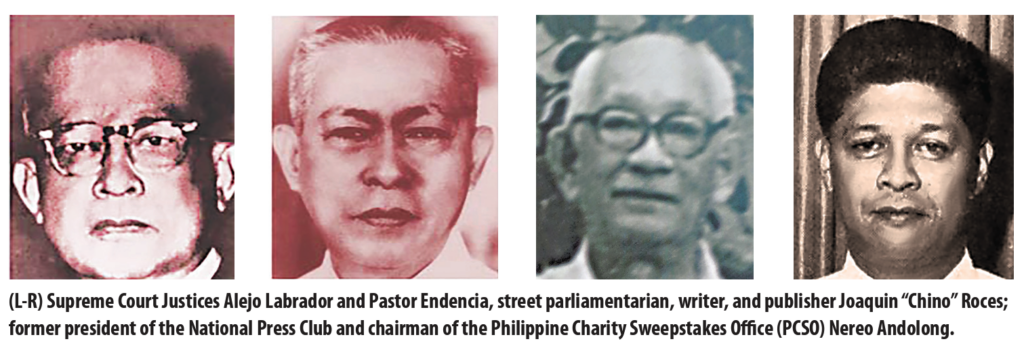

Elected as members of the first Philippine Press Council were: Ex-Justice Alejo Labrador, Ex-Justice Pastor Endencia, Dr. Gloria Feliciano, director of the U.P. Institute of Journalism and Mass Communications; Joaquin P. Roces, president of the Philippine Newspaper Publishers Association and member of the executive board of the International Press Institute; Nereo Andolong, president of the National Press Club; and Felix G. Gonzalez, editor of the Manila Daily Bulletin.

It is not clear how they were elected, by whom, and by what criteria.

ALEJO LABRADOR, PASTOR ENDENCIA

Supreme Court Justices Labrador (1894-1972) and Endencia (1890-1981) had retired from the bench before their election to the Press Council.

The practice of having judges, active and retired, in press councils has precedence in countries like India and Bangladesh.

The Philippine Press Council in this millennium would also involve a former Court of Appeals justice.

GLORIA FELICIANO

At the time of the first Press Council, Gloria Feliciano (born 1929) was a rising star, having completed in 1962 a PhD in mass communication from the University of Wisconsin and being appointed director of the UP Institute (later College) of Mass Communication on June 19, 1965, the same date RA 4363 was signed.

Former students—if not virtual disciples at UP Masscomm who idolized “GF”—are legion. I had the good fortune of enrolling in two of her classes in the 1990s. Friends say I missed her true brilliance by at least a decade. I resolved to catch those rays of radiance when they shone.

Feliciano was also known as a fighter for budget allocation, research funding, women’s rights, among others. Though not officially a “newpaperman,” Feliciano also earned a master’s in agricultural journalism, from Wisconsin.

JOAQUIN ROCES

Joaquin “Chino” Roces (1913-1988) is better known as the name of what was once Pasong Tamo street in Makati, where this publication, the Philippines Graphic, is housed.

Roces was barely a teenager in 1925, when his father Alejandro (“Moy”) Roces founded the Philippine Tribune which would become the leading English-language “peacetime” newspaper.

Claiming to be the “independent Filipino daily,” the Tribune overtook the Manila Times, which served the American and expat community, and the Philippines Herald, founded in 1920 by a group marshaled by then Senate President Manuel Quezon. A 1927 history by the Bulletin’s Carson Taylor called Moy Roces the “Hearst of the Philippines,” in reference to the American businessman whose newspaper chain Time magazine would be called as the “world’s biggest moneymaker.”

During World War II, the Japanese used the Tribune for propaganda purposes, forever dooming its good reputation. After the war, in 1946, Chino Roces resurrected the Manila Times. Founded in 1898 by an Englishman, the Manila Times was acquired by Moy Roces in 1930. The elder Roces had hibernated the Times to solidify the Tribune’s leadership.

Under Chino’s leadership, the post-war Manila Times became the best-selling broadsheet.

But with the declaration of Martial Law in 1972, it was closed down together with all the other broadsheets of the period. Many journalists were imprisoned, including Chino Roces who counted among the first media detainees of Martial Law.

Following the assassination of Senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino in 1983, Roces took part in street protests against President Ferdinand E. Marcos.

In May 1964, Roces formed the Philippine Press Institute (PPI), which is probably the organization of “newspapermen” mandated by RA4363 to form the Press Council. This is supported by the PPI website which lists Roces—and Felix Gonzalez—as charter members, along with his brother the komiks publisher Ramon Roces (who founded in July 1927 the Philippines Graphic), Carlos P. Romulo (formerly of the Herald), Bulletin publisher Hans Menzi, Manila Chronicle publisher Oscar Lopez, Sunday Punch publisher Ermin Garcia Jr., and Johnny Mercado, among others.

NEREO ANDOLONG

Known to people my age as a colonel in the defunct Constabulary, Nereo Andolong was also the chair and general manager of the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office, president of the Philippine Olympic Committee, as well as the father of actress Sandy Andolong.

Not too many knew that Andolong, a Cotabato native, advocated community journalism and “promoted the concerns of province-based journalists,” according to his Wiki page.

He would later be a Chronicle reporter and subsequently elected as National Press Club president.

FELIX G. GONZALEZ

As a child I often heard the name “Judge” Gonzalez from my mother, who was librarian at the Bulletin from 1949 to 1990.

From her I learned that “Judge” was not a real court magistrate, or a lawyer for that matter. He did not even have a college degree. But that didn’t matter because as a reporter he covered the courts with such skill that fellow reporters awarded him that nickname.

Felix “Judge” Gonzalez became Bulletin editor from 1960 until he moved to the United States in 1970.

As editor, Judge would be a legend; a terror in the newsroom, hounding reporters over poor choice of words, clumsy punctuation, inaccuracies (like, never to confuse Gonzalez with Gonzales—which both the Press Club and the PPI did), shoddy grammar, and a disregard for ethics even before it came to be paired with journalism.

Judge was said to prowl Manila’s night clubs, not to have a good time but to hunt reporters whom he suspected of leaning on politicians to pay for their drinks and sundries, in exchange for a favorable press. He would then fire the poor fellows—on the spot!

During his watch, gifts of whatever value or for whatever reason, if sent by people with the slightest hint of a vested interest, were invariably returned.

Bulletin veterans Ben Rodriguez and Jesus Bigornia described him as “walking encyclopedia, dictionary, and grammar book, all rolled into one.” Both newsmen said that Judge possessed a “fantastic memory,” but had a “cantankerous temper.”

It was probably this dedication to excellence and integrity that made him a choice for any body of journalists that is premised on ethics. Certainly, there were others cut from the same mold. But in my mind, Judge Gonzalez was the living template for the first Philippine Journalist’s Code of Ethics, which underscored accuracy, fairness, integrity, compassion, and decency.

Felix “Judge” Gonzalez became a founding member of the Press Council, the Press Institute, and the National Press Club (1955).

EDSA 1986

The EDSA Revolution of 1986 brought an end to the Marcos dictatorship and a return to press freedom.

Newspapers reopened and the PPI began to pick up the pieces.

Freedom House, which monitored media freedom from 1980 to 2017, rated the Philippine press “free” from 1987 to 1991 during the Cory Aquino Administration. This would be matched from 1998 to 2002 during the presidencies of Joseph Estrada and Gloria Arroyo.

But freedom also brought about abuses and concerns about how they might invite a backlash.

The PPI board of trustees invited its member newspapers to appoint Readers’ Advocates as some sort of check and balance. These advocates would later be known as News Ombudsmen.

Among their functions would be to receive, investigate and reply to complaints from the reading public against the newspaper or its staff, and if necessary “to supervise” the preparation of a correction or explanation.

PPI DOCUMENTS

Thanks to the PPI’s Ariel Sebellino, Sheila Remitar and Bess Zamora, I had the chance to examine PPI documents related to the Press Council. Among those I saw were:

— A letter, dated Nov. 10, 1988, from PPI executive director, Alice Villadolid, inviting every newspaper to appoint a Readers’ Advocate or Ombudsman “because of public clamor for greater responsibility among newspapermen.”

The advocate would initially represent the newspaper “management in dealing with the public on matters of ethics and standards.”

The letter also served as a notice for a first meeting on Nov. 24. Villadolid was a veteran journalist—starting in 1952 with the Chronicle and later reporting for the New York Times, Newsweek and the Philippines Graphic. In 1986 she served briefly as Press Secretary to President Cory Aquino. She was appointed executive director of the Press Council on Feb. 27, 1989.

— A letter, dated Dec. 26, 1988, from Chief Justice Marcelo Fernan to Villadolid accepting an invitation to administer on Jan. 12, 1989 the oath of office to the Readers’ Advocates.

— A statement, dated July 31, 1989, from the PPI Board, assigning to the Press Council a complaint filed by two senators against a columnist. It is the first known documented case handled by the council. Signatories included Zoilo Dejaresco Jr. of the Bohol Chronicle and PPI chairman, Eugenia Apostol/Philippine Daily Inquirer, Amado Macasaet/Malaya, Neal Cruz/Philippine Daily Globe.

— A letter, dated Aug. 1, 1989, from Villadolid inviting the Readers’ Advocates to attend a Press Council meeting on Aug. 11.

— “Weekly Work Program Status” reports in January 2000, identifying Lourdes Fernandez, then editor of Today, now editor-in-chief of the BusinessMirror, as Press Council executive director.

By January 2001, Danilo Mariano would appear in these reports as executive director. During his term, council membership was extended to include Luis Teodoro of UP Mass Comm, retired Court of Appeals Justice Ramon Mabutas Jr., and Chito Salazar of Philippine Investment Management (PHINMA) Corporation.

— A message, dated July, 6, 2001, that was marked for forwarding to “Chairman Tort,” the first time the title was used. Tort was Marvin A. Tort, then news editor of the BusinessWorld. He resigned on July 19, 2004.

— A notice of meeting, dated July 12, 2004, to the Press Council to act on a complaint filed by then Presidential Adviser and former Foreign Secretary Roberto Romulo against Philippine Star columnist Max Soliven. The council members were identified as

— Justice Ramon Mabutas Jr.

— Isagani Yambot, Inquirer

— Joy de los Reyes, Malaya

— Tes Molina, Malaya

— Bobby dela Cruz, Journal Group

— Tony Katigbak, Philippine Star

— Arnold Belleza, BusinessWorld

— Lourdes Fernandez, Today

— Lyn Resurreccion, Today

— Chito Salazar, PHINMA

— Gary Mariano, De La Salle University

Tort’s departure was marked by Romulo’s decision to go to court instead. The Council was later criticized for “failing miserably” in its attempt at self-regulation.

The commentator, Chay Florentino-Hofileña, said that “attempts by individuals to have their complaints addressed have, thus far, resulted in nothing dramatic.”

Romulo, she surmised, went to court “perhaps because” Romulo felt the council was “taking too long” to act on his complaint.

The official’s complaint, along with that of a TV network against a newspaper, were forwarded to the council on July 12. Tort said he would “highly appreciate” hearing from the members by the 16th. By the deadline, the council was one short of a vote.

On the 19th, Romulo filed his case. (Disclosure: I was one of those that failed to send feedback by the 16th, later citing midterm deadlines at the university as a reason.)

In a July 20, 2004 letter to PPI chairman Macasaet, council member and then Today editor Lourdes Fernandez, said that on the 13th, she had asked the Philippine Star to provide a copy of Romulo’s letter that he admitted had been published but had been “brutally censored.”

Fernandez wrote: “The editors [council members] needed to first judge whether or not the cutting or editing of the letter had so emasculated it as to make it totally useless in correcting whatever errors Mr. Romulo complained about.”

Fernandez added: “… seeing the clipping was a necessary starting point for deciding whether what appeared to the complainant (Romulo) as a grudging move to satisfy the right of reply (with a brutally edited letter, as he sees it) may indeed be an empty, token compliance that mocks the council’s guarantee of a right to reply; or whether in fact, it can suffice to redress the most serious grievances without jeopardizing a PPI member paper’s own editorial policy.”

On Sept. 5, 2005, the Makati Regional Trial Court dismissed Romulo’s complaint.

Shortly after Tort’s departure, I was elected chairman, a position I held for four years. The PPI files only had one case from that period, a complaint by a town official.

Mayor Esteban Coscolluela of Murcia, Negros Occidental, filed on Sept. 20, 2004 a complaint against Nimfa Leonardia, then editor of the Bacolod Visayan Daily Star. We asked the editor for an explanation and, on the 23rd, she replied. On the 28th, Mayor Coscolluela expressed satisfaction with her reply. Case resolved. Under 10 days.

I did not find nor can I recall any further cases until my resignation in 2008.

We took advantage of this lull from cases to do some housekeeping (firming up our procedures; this was where Justice Mabutas was of great help) and yard work by way of staving off possibly harmful legislation, we thought, in the form of a mandatory, court-enforceable right of reply, then sponsored by Sen. Aquilino “Nene” Pimentel.

We viewed a statutory right of reply as an infringement of press freedom because it would remove the editor’s independent decision to run a complainant’s rebuttal, reply, correction or counter-version. (See the 1974 US Supreme Court decision on Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo.)

The PPI and the Press Council arranged a meeting with the Senator, who is remembered and revered as a press-freedom fighter in the 1980s when he was Cagayan de Oro mayor.

Pimentel agreed to a “sunset” provision in exchange for a commitment from editors to promptly address right-of-reply requests. He also gave us copies of his book, Martial Law in the Philippines: My Story (Cacho Hermanos, 2006). The bill was never passed, although every now and then legislators propose similar bills. There were 12 such House bills in the past five Congresses although none at the moment.

LIBEL, CYBER LIBEL

Today, libel (and its cyber-sibling) suits continue to torment journalists. In addition, news of journalists, many of them provincial radio commentators, being murdered is becoming regular.

These murders, we also fear, can be triggered when reporters are “red-tagged.” These are symptoms that could be addressed better if complainants went to a credible, community-based media-citizen council, rather than to a national council in Manila, or to the Regional Trial Courts.

For the past two years, I have been involved with two groups that underwent a fellowship with the Swedish Sida on media self-regulation and are supporting the creation of media-citizen councils in the regions.

Last year, one group helped set up councils in Batangas, Iloilo and Davao. This year, a council was launched in Central Luzon, with more lined up in Kalibo, Dumaguete, Surigao, Gensan and the BARMM (Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao).

Another group hopes to “mainstream” existing councils in the Cordilleras, Cebu and Iloilo.

COMMUNITY COUNCILS

Guided by lessons learned from the original Press Council, we hope that the community councils will be more effective at resolving complaints. For one, these councils can be trained and accredited as mediators, conciliators and negotiators with the Department of Justice’s Alternative Dispute Resolution program.

Filipino journalists can find inspiration from Cebu, set up in 2001 with support from the PPI, and which boasts of zero libel cases. (Cherry Ann Lim of SunStar Cebu admitted that a local columnist had been convicted of libel in 2016. That case was upheld the next year by the Court of Appeals but reversed by the Supreme Court last April. At the moment, Cebu’s clean slate stands.)

A democratic society needs a free and sustainable media to provide the public with adequate and reliable information, without fear of harassment or retribution — or murder—so that ordinary citizens can make informed decisions.

While we are relatively free, we have a long way to go: Reporters Without Borders ranks the Philippine press 132nd out of 180 countries. We also need to guarantee to the public, including those officials whom the media cover, that journalists will be competent and ethical, even if once in a while they, as like any human, may err.