After the blast, the local radio frantically reported “about forty thousand people running for their lives.” Fancy that. Following up on this, I then filed my first news story on the eruption with that “massive evacuation” angle that hit the Daily Star headline the following day. It was my first and now at risk to be the last in this episode, because the Manila news desk sent a regular reporter on the morning of the second day who, from then on, took the lead and got all the frontpage credits to himself. Needless to say, I was pissed.

It was not a strong one, as compared to previous eruptions in the past. For it was brief and quite uneventful, except for a sudden rumble and the cloud of ash that mushroomed up in the sky at three in the afternoon, which quickly vanished in a hush carried by the westerlies towards the sunset. As to the massive evacuation, there was no actual running, for this was not abrupt as people not from here may think owing to media reports that tended to exaggerate. Authorities just wanted to be sure people were at a safe distance from ashfalls should there be a stronger one, which is the “standard operating procedure” of preparedness during Mayon eruptions. The evacuees were ferried by army trucks in batches, from their barangays overnight and in an orderly manner. The authorities were all familiar with disaster response and people were regularly trained what to do and where to go during emergencies, and to follow orders without many questions, something that we had been taught through the years.

I saw to it that my succeeding pieces were not short on backgrounds to present the actual situation, which were all unfortunately treated as second fiddle, if not buried in the inside pages.

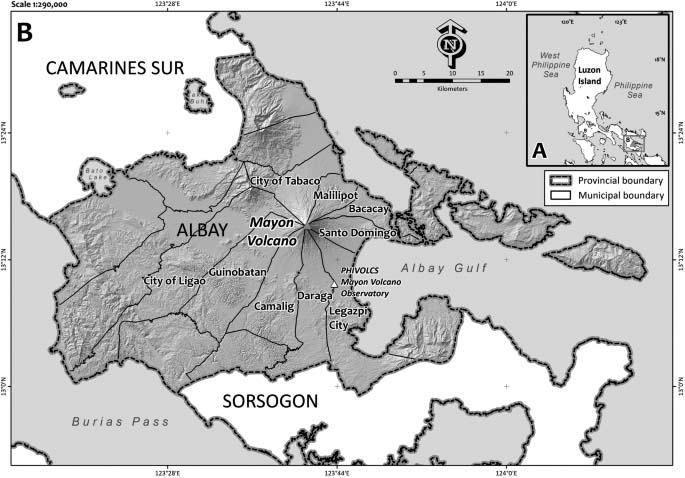

We were prepared and anticipating for the worst because the tell-tale signs were already up for about a month before this little eruption that geologists liked to call “phreatic blast”— in other words just a steam explosion – had us all engaged. Wells around the area had dried up as the base swelled due to underground pressure. Wild animals were restless, snakes, monitor lizards, and field mice along with the wildcats were observed on the run, downslope. Birds flitted low. The forest had assumed a strange resonance because, first of all, the crickets have ceased to chirp, chased away by the strong odor of sulphur and the sense of the looming danger. This was a conundrum only the locals, the children of the volcano, could somehow interpret. They were signs we had learned to heed more than the strange scientific descriptions and warnings broadcast on air. After these, the tremors began. At night we felt rocks roll deep underground like muffled reverberation of distant bass drums and at daytime the white steams wafted fast up her peak, now and again donned in a shawl of nimbus clouds, which was bad. And sure enough, the “phreatic blasts” came next in bursts, a cough of ash lasting for just about an hour, followed by an eerie calmness. We know there was something else on the heels of this because it was common knowledge that this volcano breaks her silence every eight to ten years, her own cycle of restlessness. So now, she was surely having her period. This was the summer of ‘96.

As we have thus reported, forty thousand people were now housed in school buildings in areas around the volcano, labelled as evacuation centers. There were confusions and complaints, particularly about some missing names, some fifty or so people still unaccounted for on day three, from one barangay. We all knew it was natural for manual lists to miss a lot during emergencies, and for now, this was relegated to the common problems that would be resolved in no time. On this, we all agreed.

The evacuees are tended to by relief workers with a regular supply of foodstuffs, water, and sanitary necessities. Though, yes, everybody was uneasy. Imagine a school of fish from the river dumped in a drum of water. There was no way to impose order since it takes time to break routines. A standout case was that of disappearing couples breaching the lines to their homes in known risk areas, for a lot of reasons – some probably real, mostly imagined, among them, that they have to secure their properties, tend to the animals, the chickens, or feed the hogs. Military patrols would surprise them around and haul them back, flushed.

‘Feed the hogs.’ Clueless, someone pitches the idea of evacuating the animals as well, over which a scholarly debate ensues, until someone gets the cue. “As if you didn’t know or are you really that daft? Husbands and wives, they just needed the homey privacy.” He was our new governor who overwhelmingly won the elections just last May. “Buddy.” Just Buddy, he insisted during the campaigns, so now everyone does call him Buddy.

“I know Buddy, but there’s an emergency going on for God’s sake, these people, really?” exclaims the exasperated head of the evacuation committee, who is a colonel in the army. It was the fourth day, and we were at an emergency meeting called for the purpose of resolving the sudden disappearances of evacuees.

“But then that’s even damn urgent reason to evacuate all that moves, so no one will have good reasons to bolt camp, right?” Buddy philosophizes, his hands in the air. “Just because there’s already an eruption doesn’t mean you don’t get to…you know what, make love!” This brings the house down.

Everyone agreed with the governor. Because on the one hand, we all know the soldiers could not completely stop couples from breaching the boundaries of safety and risk, of even life and death, for humane reasons. On the other, Buddy pointed out that – between husband and wife – it is always worth the risk. And, yes, we all concurred, slapping our knees amid the explosion of ribald laughter. We were all having a field day. So far, this issue was new. Because authorities did not have this problem during past eruptions, or that they did but hardly gave weight to it and looked the other way. But Buddy was young, a man of the street, even ahead of his time, and no doubt wiser than his predecessors and probably any of us around. Buddy, it seems, simply plucked solutions out of thin air, and problems, too.

So, thanks to Buddy, “feeding the hogs” had become our favorite catchphrase in this part of the world, up to this day.

Lest we forget, this is Mayon, the world’s most perfect-cone volcano, postcard perfect, of clear blue skies and spotlessly white clouds that is no doubt also mesmerizing in her tantrums. Danger lurks, but the whole scenario still radiates an aura of a festivity, especially at the evacuation centers, never mind that authorities have to move heaven and earth sourcing out supplies to make ends meet, maintain cleanliness in the overflowing comfort rooms, sponsor the nightly shows and awards, the beauty contests, and dances, plus the movie shows to ward off boredom and enforce peace in this crowded world. And for as long as everyone was in the meantime alive and safe. The police maintained peace and order in the evacuation centers while soldiers guarded the boundaries to the danger zones and the no man’s lands, arresting those who broke through the line, tweaking ears of “eloping couples,” as it had now become a familiar entry in the police blotters. Yesterday Buddy declared the state of calamity to allow cities and towns to spend extra on foods and medicines, and imposed curfew in the evacuation centers, six-to-six. No one complained.

Today, we were in the media briefing room of the provincial building, listening to the radio. The barangay captain of Santa Monica, a village situated up the six-kilometer permanent danger zone, went live on air complaining about the still curiously incomplete list from the city welfare office. It appears that he was missing “fifty or so” people both from the list and in actual headcount. He was “turning stones” in an effort to find them, getting radio interviews, touring every room in other evacuation centers in case they were booked in the wrong clusters, or went astray.

“Could be feeding the hogs, eh,”he radio announcer joked at the distraught official. “Saburay-ni-ina-nya!” the official curses, sending us all down in wild guffaws, once more slapping our knees. The poor announcer did not have the chance to briefly cut that off air and radio management went crazy on him.

Each village was assigned its own cluster of evacuation centers for which endless dry runs were conducted so people would actually know where to go and not get lost during emergencies. So where had some “fifty or so” people actually gone?

“An incomplete list is one thing, a lacking headcount is another,” Buddy whispered to my ear when I cornered him for comment. “This concerns some fifty-seven people! This is no joke! Let’s all look around for them, Tom.” He pats my back, and I had the sudden feeling of being among his trusted friends now.

“Here, it actually feels one lives by the day, as what the wise exactly preach the ideal existence should be,” Roque the Daily Star’s reporter quipped over beers the other night in our hangout.

Yes, I guess so, Roque.

This is the guy sent by the desk on the second day of the eruption, fully packed, to “assist” me. He was with three other representatives of Manila dailies, all “armed to the teeth.” As the correspondent covering the Bicol region, I had been with the Daily Star since its maiden issue, which was a day after the “People Power Revolt,” and now familiar with its lingo and grind. Several times management had offered me to work in Manila as a reporter, way back when Roque was still with another newspaper, but I turned them all down because I had to leave my family behind until I had enough money to move to the metropolis. In fact, I was almost tempted, if not for the wife who heatedly opposed this arrangement.

Roque is now indiscriminately clicking his Nikon N90 at people milling around, at the ladies most especially, who would gamely wave their hands and pose for him. “Don’t waste your films, Roque.” But the old man goes on showing off, spending rolls of the Daily Star’s films for nothing. These were times when people would stare at reporters with their cameras and those large press cards dangling over their media vests, as people would celebrities. These guys also loved the attention, especially when bored.

One of my favorite anecdotes is about a reporter who was a bit confused during one action-packed coverage in the mountains when an old woman – without warning – kissed his hand and asked him to pray for her long dead husband. It was obvious she misread the reporter’s ID card marked “PRESS” in red.

Days after the eruption, tourists flocked in droves, and a few thrill seekers were caught sneaking up to no man’s land and beyond. They were not feeding the hogs. They were there for the thrill of getting a closer look at the hardened, smouldering lava dikes, taking souvenir shots of what would amount to “selfies” in those days.

I kept track of the daily flow, aware that unless a “big blast” occurred, any piece was nothing but records of the “humdrum of every day.”

“I could be ordered home if nothing earth-shaking occured,” Roque ventured. Despite good hotel accommodation, daily mobility ,and food allowances, a package that is the envy of the lot like me, the veteran in him longed for some action and not a vacation. He had been in countless actions in the past decade, his kind of life – the bloody Muslim secessionist wars in Mindanao and the military-NPA skirmishes, topped with earthquakes and killer typhoons, and this Mayon engagement bored him to death.

“No one really knows what could happen next, but what I know is the desk is boss.”

Anyway, the idea that Roque wouold be recalled was a welcome twist. It meant I got to write all the stories, once more get by-lined on the front page, and which meant a better pay for the whole duration of this eruption, or for as long as there was something worth the “fax” to appease my editor.

That was yesterday, the fourth day of the eruption, and Roque flew out to Manila this morning with the horde of his kind – glad for not wasting anymore time –leaving us behind, the local boys giggling.

“I’ll fly back in soon as something big happens. Phone in soon as she kills, and I’ll be right beside you,” Roque yells through the din of the engines as he boarded his plane to Manila.

Yeah.

I knew this would be a protracted coverage and management was not spending any more money for a long wait. We correspondents were always jealous of the “Manila boys.” They leaned on us for backgrounders and treated us mostly as their guides, while they got all the credits and the celebrity status.

So now I am writing the state of calamity story and the confusing evacuee count. Also, there were plans to haul out the entire eight-kilometer population because it was now July, a rainy – nay – stormy month that could trigger lahar. It’s a prospect of moving some 80,0000 people!

But as usual, nothing big was happening yet. In the day, like a damn tourist, I would get a stiff neck looking up at the ashes from her crater towards a red sunset, then at the rivers of fire trickling down her dark slopes at night. Each time, I was always tempted to ask myself, “what the hell am I doing here?” thinking of other jobs that could pay better.

Tourists were eternally mesmerized by all this, though. They would hang around till the wee hours of the morning, drinking and eating grilled fish and chicken, squid, and tusuk-tusok at parks and beaches or the floating beer gardens in the gulf, watching the fireworks reflected on the calm sea “as lovers sit on rocks swearing eternal fealty on this end-of-the-world backdrop.” Isn’t that lovely? I already wrote that once, twice, and my editor said ha-ha over the phone after I sent a rehash today.

“I told you fax, not fucks.”

He as the devil incarnate. Someone should throw this editor into the crater. But a wedding was scheduled next week, at the church on a hill that stands against a full view of the volcano, which I planned to write about. That sounds like fax. Anyhow, only the editor had the right to say what a good copy was, so he would always remind us.

And, yes, the residents would often wonder why foreigners came, spend their money just to be here – perhaps climb up whenwas calm – when they never gave a damn thought about it. Tourists flock mostly in the summer – eruption or no eruption – for a spectacle and a little adventure. And we, the natives just stayed, with nowhere to go but here. We were raised here, plant and grow vegetables on her fertile grounds, and survive. My father tended a broad patch of land at the foot of the volcano when he was alive, living out the risks, walking on a tightrope to send me and my siblings to school. Tomatoes paid for my journalism course and my friends all called me Tom, or Tomas, even up to now. I was not mad about it. Tom surely sounds better than my actual name.

As a reporter of events, I was no doubt guilty of some selfish biddings that, in the first place, I should just keep to myself. That, if Mayon did more than her cough-and-drool show, I perfectly knew what was in store for me in a headline or two, which was a better pay. Like my father, I, too, walkes the tightrope and had to provide for my family, send my two girls to school. Many times, I was obliged to help my father in the fields, but it was obvious I hated farming, so he would just send me home early scratching his bald head and did all the work himself. And unlike those salaried guys such as Roque, I didn’t get paid if I didn’t have a story. The bigger the story, the bigger the by-line, the bigger the pay. It’s was simple as that. My next of kins, and the wife most particularly, wondered why I did what I did with great effort and so much time yet earned so little. I covered this up by doubling as editor of two local weekly newspapers – The Mayon Times and The Sunday Volcano – which gave me a total of a thousand pesos a week. When I would save enough money, I planned to put up my own newspaper, The Weekly Eruption. I wasn’t sure if people would patronize it, but I would do my best.

During mornings when the strong westerlies carried the ash away, the skies would be blue. The volcano would be still as a photograph, the prehistoric landmark, tranquil until a little tremor shook the ground, and her tip blew up smoke once more for a little show. Then these clouds would land around the slope like a shawl, swirling around her base like magic rings, an ancient skirt of ash, mysterious, hypnotic. She was a spectacle at daytime as she was at night. Maybe if I were from a distant land, I, too, would try to save enough money and travel halfway around the globe to watch this scene. At least for once.

Nevertheless, you must not underestimate Mayon Volcano. One or two records of previous cataclysmic blasts were no fun. Take, for example, the case of Cagsawa Ruins, her famous postcard partner, which she buried in mud days after she blew her top in 1814, along with 1,000 or so residents, who had earlier succumbed to injuries brought by showers of flaming lavas that hardened into rocks and stones in the air, and rains of sands, pebbles of lapis lazuli, or were suffocated in sulfuric ashfall. The survivors gathered their dead, piled them up inside the church waiting for things to settle down, hoping to give them decent burials. Mayon lent a hand with a flash flood, and buried half of the church and the little pueblo as well. Fray Francisco Aragoneses, the reporter of that event, was so vivid to the point of fiction. I envied the guy. He got the headline of the century by sheer luck. Because all the other eruptions that were not reported in detail – particularly the more recent ones – were mere ash puffs compared to that big one in 1814, despite earth-shattering scenarios forecast by both palmists and scientists. One of these creative guesses was a horrific prediction that Mayon erupts sideways, through a crevice facing Legazpi City, burying our dear little city deep into the Albay gulf. Well, that was my first banner story as a newbie, years ago, but over which the tourism buffs ganged up on me for days, accusing me of being anti-development because that piece would surely scare away visitors and destroy our tourism. They were wrong. Instead, tourists came in droves eager to witness the cataclysm.

But I believed this eruption is no different from her cough-and-drool ones. On air, a geologist was answering questions from a commentator.

“Will there be a big blast, sir?”

“That is always a possibility.”

“Can you give as an idea when this will happen, more or less?”

“Frankly, we are not sure. Everything will depend on the volume of carbon dioxide emissions, the ash, and the magma movement. The base should bloat more, the noise goes louder. I think it’s nowhere near yet…”

“Can’t we have a guess, at least?”

“Oh, no. We can’t do that. This is supposed to be based on scientific facts. But then again, you already knew volcanology is not a perfect science. At least not yet…”

“So, it’s not yet safe to send the evacuees home…?”

“You are right, it’s not safe…”

And the conversation went on and on and on, taking us all on a hazy ride with the rat in a wheel.

One of the more pressing concerns was that the local governments affected by the emergency were not sure now whether they could feed the evacuees for longer than two weeks, so they pried a little pledge from the national government for aids. And, yes, health and sanitation were a problem which should be religiously dealt with. On a happy note, the good governor finally issue\d a memo to move the animals to areas near the evacuation centers – the chickens and hogs in makeshift coops and pens – so their owners could tend to them as they wished and not force their way through the barricades and get lost. Relocating another five thousand animals won’t hurt if it would save even just a single individual, says Buddy. Each barangay organized a team of volunteers to do this. And as a bonus, Buddy requested the Department of Social Welfare and Development to assign what he called “conjugal rooms” in evacuation centers, for “couples who need to copulate.” Yes, “copulate” was the term he used in the memo as chair of the disaster council. He said this should stop couples from “eloping.” Didn’t I tell you this governor was good?

I wanted to write the conjugal room piece as a human-interest story and perhaps the animal evacuation if I could just get the perfect slant for my sadistic editor, so I headed to the media briefing room where the other correspondents lazily chatted over instant coffees and cigarettes, ogling me suspiciously.

“Hey, Tom, what do we get to masturbate this time?” one of the kibitzing bastards impudently asked as I rummaged for bond paper in the drawers. So, I stopped what I was doing and just sat there, quietly losing inspiration and opting to write my pieces at home instead.

I pretended to doze off, chin on my palms, ruminating, when commotion broke out outside the building. The blaring sound of alarm and revving of car engines sent us all on our feet to the wide window of the ground floor, which was just a stone’s throw away from the huge parking lot where trouble was transpiring.

We watched confused as people ran around in panic, screaming as authorities barked orders on megaphones directing traffic and shooing people away from the path of oncoming vehicles to the parking lot. It was like we are watching the world in a riot on a large movie screen, unable to do or say something, as a patrol car and an ambulance maneuvered to park under the blistering afternoon heat, sirens wailing and emergency lights ominously flashing. Then a government dump truck rolled in amid the crowd next to the ambulance, its yellow public works paint now gray with ash, as men in orange helmets and vests – equally covered in dirt, visibly sweating and haggard looking – clambering around it jumped soon as the tires squealed to a halt, literally hitting the ground running, like soldiers bound for combat. And as if on cue, policemen shouted at the crowd and hastily cordoned the area as the orange guys proceeded to unload the cargos and lay them down one after the other over green canvasses now on the pavement. They were corpses, must be around twenty of them according to my own hasty count, visibly of adults and children, all unrecognizable because they were covered in thick plaster of ash and mud, their limbs sticking out hard like dried, gray branches of driftwoods on the shore. After a while, another dump truck came ferrying more victims, more bodies in similar condition, which were laid down right in front of us under the sun, as we gaped in shock. And another vehicle, someone shouted, with more victims on its way…make way, make way!

The warm air from the pavement hit us with the stench of death, and we attempted to ward it off using the electric fans and covering our noses with handkerchiefs, which did not help much. Most of those inside the room, the kibitzers and government employees, rushed out to the corridors wailing and yelling in terror. I had to stay and watch for details. Up ahead against the clear blue skies, I glanced at the tip of Mayon Volcano through the window, sticking out of the low clouds, floating in a mirage.

Clearly, that which we dreaded, the odds that we prayed against, had in fact already transpired.

Amid the chaos, Engineer Ramos who headed the disaster rescue and recovery team trotted inside the yellow cordon that prevented the restless and thickening crowd from trampling on the bodies, raising his hands to summon silence and make a statement.

“We would like to announce that we already found the missing persons from the Santa Monica list, a problem we all were engrossed with from the start. So unlucky, they were already dead for six days now. They were burned alive so to speak, pardon my language, but that’s the only way we can perfectly describe what misfortune had befallen them, for they were charred beyond recognition.” This sent the crowd into hysterics, some crossing themselves in silent prayers, senselessly hoping they didn’t have relatives or among the victims.

They were farmers and their family members, kins and co-workers, who were tending to their plantations during that Monday blast that was brief but proved to be deadly. As was later explained by geologists, the rain of airborne ash, with embers a thousandfold hotter than boiling point – the breath of hell, as Engineer Ramos described it – were blown by the wind down the Southern sector of the volcano and in minutes engulfed the farms in flames. It consumed everything, the trees and the vegetations and the work animals and, yes, the people gathering their final harvests for the season.

There was but one survivor in the tragedy, a woman who was fortunate enough to be far from the fields washing clothes in a nearby stream, who witnessed the swiftly spreading inferno and thanks to her instincts, she wasted no time fleeing but not without getting hurt herself. Specks of ash – elemental, arcane dusts summoned from the earth – caught up with her, searing her hair and her back as she fled, eating up into her flesh, her scalp – as potent and exacting, ravenous, other worldly. Despite the pain, she went on running downslope in flames, for how long she didn’t know, the soles of her bare feet gnawed and slashed by the sharp rocks and thorns along the way – and yes, burned and skinned – stumbling near the road in the throes of mortality. Soldiers found the woman the following morning miraculously breathing and rushed her to the hospital. No one had the idea of the circumstances that she had been through until the afternoon of the fourth day when she suddenly woke up from sedation, or comma, with a loud scream, lying face down on the bed due to her burns, to tell her tale drawn from her own nightmare, in between cries of pain and terror, and the agony of loss.

Buddy dispatched search and rescue teams to the area early the next day and volunteers, composed mostly of firemen, were shocked to find the dead, body after body, from the still smoking heaps at the burnt plantations.

At the nearby PLDT station, I read my sketchy report while my sadistic editor took my dictation, fired up but was noticeably subdued and modest in following up details. Then he passed the line on to the publisher herself, who asked me how I was doing, is your family safe and please send my regards to them, I sincerely hope you don’t have a relative in the list…I don’t know what to say, but please send our condolences to the bereaved, Tom…Tom?

“Of course, Madam, thank you. Frankly I still don’t have details on the identities of the victims, but we have the list of the missing, so Buddy said it must be them.”

“Excuse me, who’s Buddy, Tom?”

“Sorry, he’s the governor, Madam.”

“I see. So that’s it. Meanwhile, Roque is in Davao for now. It’s all yours, I trust that you can do this. So, I won’t take much of your time, please keep safe and rest assured you will be duly compensated…” Her voice, high pitch but refined, rang in my ears as the line went dead.

Suddenly I felt a headline no longer mattered to me that much. I might have wished for it many times but realized not at such a cost. I’d be good with tourism pieces.

Banging on the typewriter at the media briefing room for my second lead, I paused to eavesdrop outside – just a few paces away from the window – as authorities for the nth time cross-checked the dead with the Santa Monica list. “Fifty-seven in all, the missing all accounted for, men, women, and children.” Buddy was standing there, one arm across the barangay captain’s shoulders, who was weeping quietly.

A tabloid guy sitting next to me and busy translating his piece in Tagalog, which he had copied from mine to the letter, told me he’d better round up his death count to sixty.

This is not a number’s game, pal. Be careful what you write…

He retorted matter-of-factly that he is dead sure the death count will hit that figure soon.

I swore that if I was not busy as hell for the front-page deadline, I would have right at that very moment, banged the World War II vintage Underwood typewriter on his useless little head. This would have made my death count fifty-eight.

The volcano gave off another blast the following week, bigger in magnitude, sending another 80,000 people to the evacuation centers, after which it calmed down completely. I had my daily headlines in the Star, with my by-line for a straight week and some more days after that. The wire agencies got my number in an instant and were calling me at the briefing room and at home day and night for follow-ups, being “the only reliable reporter in the area who knows the people, the terrain, and the volcano by heart.” So, that’s what they said. I was on for long-distance interviews with Manila broadcast networks several times. I hardly realized I had been one of the most sought-after guys by other news networks in this episode, perhaps next only to Buddy. And Buddy, who was active as ever, said he liked the way how straight forward I wrote my news reports, glad that I always put his name as a source and hinted on recruiting me in his young administration. “We lack good fellows, you know…”

The victims were not identified individually and were buried in a mass grave in a remote cemetery, hastily put up and declared for the purpose by the provincial government, with a single cross as a marker and a tombstone with a brief and almost apologetic epitaph written by Buddy himself. Under it were listed their names in alphabetical order, and the single cause of death: Ashfall.