No one, least of all her schoolmates at St. Celestina’s Academy, would have pictured Chona Laon Badoy as the Mayor of San Semilla in Negros Occidental. Chona herself had never aspired for political office, but only to public service, as her in-laws loftily put it. Her rise was not entirely unexpected, though, since her husband Erwin Badoy was the lone district representative, as his father and his grandfather had been before him. Due to an unfortunate quarrel between Erwin and his younger brother Dennis over the management of certain Badoy family corporations and the benefits from some choice government concessions, Dennis had refused to settle for mayor, but went up against his older brother for the lone Congressional seat. Worse, Dennis had allied himself with a political rival who was running for mayor of San Semilla. Thus Erwin had insisted that Chona run for mayor against Dennis’s ally. Dennis’s own wife was already mayor of her own hometown across the Madyaas Mountains, so, it was an especially sweet triumph when Chona won as mayor, too.

Erwin and Dennis Badoy had raced to herd as many workers from their haciendas, rural banks, construction firms, feed and sugar mills—along with all their family members who could vote—onto farm vehicles, buses and trucks, and ferried them to and from the polling precincts. Many voted multiple times under the watchful eyes of foremen and supervisors loyal to either brother. They did not really mind as they received P50 each (more than what they would earn in a day) and an ample merienda as well.

Elections were an occasion for merriment and mayhem. Some houses were burned and a foreman at El Dorado sugar central, which Dennis controlled, was killed, while a driver from Erwin’s Consolidated Concrete Aggregates disappeared. But blood was still thicker than water, and the violence was contained and limited to their underlings, in keeping with the proverbial ruse of slaughtering the chicken to frighten the monkey. In San Semilla, the monkeys told no tales.

Rock bands from Olongapo and Angeles, actors and singers from Manila, were flown in to entertain the crowds of prospective voters at campaign rallies. Chona found it tiresome. The entertainment was not up to her standards. She despised most local television programming and had a satellite dish in her home. Also, the endless shaking of hands was such an unhygienic but necessary practice. A distant cousin on the Badoy side, a retired accountant known as Aunty Meding, was assigned to be Chona’s personal assistant. Aunty Meding had spent all her life in San Semilla, so she would be responsible for coaching Chona, who had spent most of her life in Forbes Park rather than in her native Pontevedra, on how best to get along with her constituents. Although Aunty Meding with unfailing sweetness called everyone palangga, she knew how to make them toe the line.

Aunty Meding saw to all of Chona’s necessary comforts such as ensuring that there was always a well-stocked cooler of cold drinks and snacks in the campaign. Whenever they left a bag full of their garbage at a barangay, the children happily swooped down upon their empties, dribbling the last drops of soda from the aluminum cans into their laughing mouths, licking the rims, scrabbling after the empty cardboard canisters of chips and scooping up the crumbs with their grimy fingers. The sight made Chona nearly faint with disgust but she tried not to show it, just as she had learned that she must never let the peasants see how she vigorously rubbed her hands with 70% proof ethyl alcohol after every hand-shaking campaign sortie. She tried to make use of what she had learned in those meditation classes with a Vietnamese monk near Zurich where she had gone to a finishing school. She practiced breathing from her hara with gentle exhalations to avoid visibly stiffening whenever some overly enthusiastic peasants, thrilled at being so close to their representative and landlord’s pretty young wife, managed to wriggle past her burly bodyguards to actually embrace her or to adoringly stroke her forearms while marveling: Kaguwapa gid kay inday—daw sa artista! (How pretty our Inday is—just like a movie star!)

The election battle between Dennis and Erwin was protracted with Dennis filing an electoral protest. Meanwhile, Chona was proclaimed the mayor of San Semilla and sworn in by her father-in-law, the governor. Hector Badoy was not pleased over the rift in their family but blamed Dennis for not deferring to his manong Erwin.

After the rigors of the mayoralty campaign, Chona was aghast that Erwin expected her to report to the Mayor’s Office every day, and to preside over all the municipal council meetings. He was so serious now, unlike the fun-loving and easy going beau of their schooldays. It had been so long since they had a real party, the kind where they would serve various psycho-tropics in tiny condiment dishes, just like appetizers, for all their guests to partake of. They no longer saw many of their old friends, just the dull Chinese businessmen who were his financial backers, partners, and other political cohorts.

From his point of view, Erwin had simply matured. He warned her not to stand in the way of his greater ambitions. She was expected to pull her weight. “Your family will benefit, too,” he bluntly told her. “I know all about their behest loans. We have to show that we are in control. There are always wolves waiting at the door, ready to pounce on you and tear your throat once you show you’re weak.”

He quite terrified Chona when he talked to her that way, and she longed to be able to take a break in Manila especially now that Digna, her first cousin twice over, was visiting from Singapore. Like an obedient daughter of the clan, Digna had married the Chinese sugar trader from Singapore to whom she had been promised ever since she had been a high-school junior in St. Celestina’s Academy. He was often abroad on business, so, she was usually left to her own devices. Early in the marriage, she had done her duty and produced three little sons for him, each one undeniably Mongol in features, for Digna herself was of the dark mestiza turco, or what Filipinos term bombayin type with olive skin, vivid black eyebrows, and large doe eyes.

Digna was often in Manila to consult with her interior decorator as she had decided to redecorate the verandah of their large luxurious home in Katong with Filipino fabrics and modern art. She urged Chona to come over so that they could take a quick trip to Hong Kong to shop for new wardrobes. As a mayor, she should have more mayoral clothes, Chona mused, so Erwin might relent and allow her to go after the municipal board meeting that week. There were covert whispers among the councilors that the Mayora was not even a college graduate so she had to look the part at least.

After high school at St. Celestina’s, Chona and Digna spent two years at the Villa Alpin Blanc, a finishing school in Zurich, where they had learned to ski and had mastered the intricacies of eating a banana with a knife and fork, and sectioning the orange on a plate, so that the rind fell away like the petals of an opening flower. Again there were nasty jokes, from their political and business foes, that the lowly hawkers who sold pineapples and green mangos from the wooden carts mounted with glass cupboards along the streets of Manila, had the same skills without having to go to a Swiss finishing school. Chona could also converse in passable French, but this meant nothing in San Semilla society, where the lingua franca was either Cebuano or Hiligaynon. She was especially irked when those thick Bisayan tongues addressed her as Mayor Baduy or even Badu-uy which was Metro-Manila slang for uncouth and tasteless. She was certain that many of them knew how to pronounce her name properly but chose not to. She had tired of telling them, it’s oy as in “boy” so it’s Badoy as they persisted in pronouncing it as Bah-du-uy. She suspected they were secretly amused by her discomfiture.

During the first provincial board meeting, the matter arose of that repulsive Reuters photo of the emaciated boy during the tiempos muertos, which had been published in reputable newspapers all over the world like the New York Times, Le Monde, and the London Observer. All that they had were photocopies of the alarming publications or articles smuggled in by travelers or secretly mailed by trouble-making Filipinos abroad. The foreign press was censored as much as possible. The image was undeniably disturbing—one would think the Philippines was Biafra. Often, the offensive image was juxtaposed with photos of the legendary and flamboyant First Madame in her jewels and ball gowns. The article was far worse: an oft- repeated refrain condemning the persistence of the evils of the hacienda, particularly the sacada system and the great social inequities in the Philippines as epitomized in the sugar-producing provinces.

The plight of the starving children of the sugar plantation workers was an international scandal. Like other towns that depended on sugar, San Semilla had smarted at the implication of its guilt and the international judgmental finger wagging. It was small consolation that the child was from one of the other haciendas, and not from any of the farms belonging to either the Badoy or Laon families because they knew better than to allow any journalists in.

“Those media people are all tonto, mga demonyo,” Hector Badoy, Chona’s father-in-law, had virtuously warned. Now that Erwin was Congressman, he could relax as the provincial governor and mostly just played golf or went to cockfights. He had a farm full of fighting cocks. Recently, a popular broadsheet columnist had asked him through an intermediary for two of his prize-winning cockers as a gift, which was why the Gob as they called him, felt so strongly on the subject of mulcting media men. The gift was a preventative measure to suppress any publicity of the Gob’s rumored role in the smuggling out of sugar and the smuggling in of cigarettes and gasoline. The intermediary had assured him this would be cheaper in the long run than having to do damage control, or worse arouse the suspicions of the government authorities that the Gob was holding out on them.

“The media are all ACDC (Attack and Collect or Defend and Collect), especially the ones on the radio. The radio stations shouldn’t have reopened. Right after martial law, it was so peaceful. Now they keep talking about Negros as a social volcano. It has been like this for over a hundred years and it has never erupted. Those idiots don’t realize that this volcano is extinct.”

Erwin Badoy never gave interviews unless his PR had first coached the journalist thoroughly. Chona had been warned that she must not agree to any unrehearsed or unmanaged interviews either, not even for the Lifestyle or Fashion and Beauty sections. Her cousin Digna had been featured yachting with taipans in the Asian edition of Mirabella, and although Chona loved her like a sister, she could not help feeling that life was unfair. She was taller and lighter- skinned than Digna. It was generally agreed she was the prettier one and yet here she was forced to stay in the background.

In the wake of the swirl of unflattering news stories about the sugar industry and the lifestyles of the sugar barons, there came a delegation from a conference called the Asia Pacific Women’s Consortium Against Poverty and Underdevelopment, or AWCAPU, which when phonetically pronounced, sounded to Chona, like an exotic Australian bird. Spurred by that unfortunate photo, they wanted to conduct a fact-finding mission on the conditions of women farm workers in the sugar cane plantations. The Indian delegate had airily declared that she wanted to enter the hovel of a typical farm laborer so that she could see for herself what Filipino poverty looked like. Aunty Meding and Chona could not dissuade her and had no choice but to stumble after this determined Indian Ph.D. as she hoisted the skirt of her sari up to her calves and merrily sloshed along the muddy trail to such a worker’s house. They crossed the worn bamboo threshold and stood in their muddy shoes on the hard earthen floor, packed and worn smooth by necessarily bare feet. The surprised peasant wife who lived there, had scrambled for a cloth while her children who were too young to be in school cowered together, and looked at the odd strangers with frightened yet fascinated eyes.

Chona had never been inside a farm laborer’s house before and felt a vague unease. She whispered futilely, “Indi lang, tiya’y. Wa-ay kaso.” (Please, Aunty, it’s really nothing. Don’t trouble yourself.) But the peasant woman doggedly continued to dab at her ruined Gucci slides. Chona could not bear to look at her bowed head and her hunched, narrow, quivering shoulders, and so she surveyed the tiny room instead. On the wall over a low table, there were tacked three sheets of white paper where a shaky hand, palsied perhaps from a lifetime of pulling weeds or hoisting sheaves of sugar cane, had painstakingly traced with a pencil, three kinds of flowers: red hibiscus, yellow frangipani, and pink pitimini rosebuds. The petals and leaves had been delicately colored in with the lightest of touches and uniform slanting strokes, with the intent of using the precious crayons sparingly, as these must be made to last as long as possible.

Chona realized that even in these spare surroundings, there was an attempt at witnessing beauty and rendering it, pathetically cliched and stilted as this attempt might be. She decided that “Beauty by Badoy” would make a nice slogan for her administration. The First Madame claimed to be a champion of goodness, truth, and beauty, so her efforts in San Semilla would surely endear her to the omnipotent one, and give her an edge over all the other high-society darlings, jostling and jockeying to get in closest to the most powerful woman in the land. Chona as a young, pretty elected government official with the right family pedigree, would be a winner.

The Indian Ph.D. had stood still to allow the peasant woman’s ministrations to her sandal-clad feet. The mud soaked through the flimsy cotton T-shirt she was using as a rag, so she had to use yet another of her family’s few clean items of clothing. With her imperious academic’s gaze, the Indian Ph.D. studiously took in the bareness of the single room with the lone frayed sleeping mat tightly rolled up and standing against one corner. The family’s threadbare blankets and their meager store of clothes were neatly folded and kept inside an old milk carton which served as their closet. Aunty Meding had to translate the Indian delegate’s many questions and the peasant woman’s hesitant, shyly whispered answers about the family composition, the incidence of contagious diseases, the average number of years of schooling children had and such. “So, poverty in the Philippines is not much different from India,” she had noted approvingly as they left while the peasant woman remained bent over.

But there was a positive side of this revelation to the world of the scandalous existence of starving and stunted children amidst the antebellum-style mansions of the wealthy plantation owners. International aid and development foundations that had made it their business to help the poor of the so-called Third World had swarmed upon the haciendas, and their offers of livelihood for the plantation laborers during tiempos muertos had reached San Semilla. As the workers were not organized, the foreign foundations had to go through the hacienda owners just the same. Aunty Meding with her native perspicacity honed from years of sharp accounting practice, and her hardened old maid’s innate intuitiveness at finding a way to make a little something extra for herself to add to her already substantial nest egg (who else would provide for her in her old age, after all, and she was not about to become a burden to her many nephews and nieces), had immediately seen how to get foreign charities to put up the capital for the haciendero wives to set up their own little workshops and ateliers.

“Inday Chona, as the first woman mayor of San Semilla, you should champion our gender and involve the women. It is up to you to empower the poor mothers who must feed their children,” loftily exhorted Aunty Meding. She could already taste this new opportunity to exploit this new-found resource, which was the farm women. Their men had been bled dry for all that they were worth, many in debt bondage to the contratista for longer than the Biblical three score years and ten—an age which few of them ever reached. Some were debts they had incurred. Others were the only inheritance bequeathed upon them by their dead forbears or as loan co-makers or guarantors to co-workers who had defaulted. The women were a natural target as sewing and handicrafts were still in the realm of women’s work. During tiempos muertos, many of the men would attempt fishing or hire themselves out temporarily as construction workers in the cities, while the women continued with their unpaid housework and tending their home gardens.

Already Aunty Meding envisioned how the lollygagging peasant wives and daughters would be trained and transformed into the well-oiled cogs of a fledgling handicrafts export business to be initially funded by foreign-aid organizations. As an ostensibly charitable social enterprise, she was certain this would be virtually tax exempt. The women would be put to work on a quota basis. They were unskilled, so, while they learned (which might take them weeks), they would not get paid. But their training would be free. After their training, anything which they made that still failed to pass the standards set by quality control would be rejected, so they would not get paid for those either. In order to instill discipline and a sense of good Christian stewardship, any materials that they wasted would also be deducted from their quota.

“If they were only more resourceful, they could feed their families with coconuts, you know.” Chona observed. She had never considered herself business-minded but prided herself on being open-minded. “I read somewhere that the fruits of one coconut tree can feed a family of three for a year. They must also have a source of Vitamin C for a balanced diet, so perhaps they can drink boiled batwan, or kalamansi juice. But they would need several coconut trees, I expect, since most of them have more than one child, which is another problem, their having all these children whom they cannot feed or send to school. They are so funny that way,” she added. Funny as in ka-funny gid was a favorite expression of light exasperation and dismissal among the soignee members of Chona’s class charged with exercising noblesse oblige.

Aunty Meding nodded vigorously. “There are other opportunities, especially in livelihood and skills training,” she pressed on. “There is a proposal for capacity-building from Halong Bisaya which is funded by the Third World Development Foundation.”

Chona was all for having any capacities that the plantation womenfolk might possess, built up and encouraged. Then perhaps they would be less likely to starve so scandalously and so publicly in front of the watching world. This might also bring in some favorable publicity for her as the forward-looking and innovative first woman mayor of San Semilla, in complete antithesis to that wretched starveling boy. She would epitomize Beauty by Badoy—she liked the sound of this even more. She would convince Erwin that a little well-managed publicity could only be good for their province.

Then in what she considered an ah ha! moment of destiny, Chona opened the pages of a local fashion magazine to a color spread featuring her old friend and fellow Celestinian from their long ago schooldays: Mayita Dela Strada of San Miguel, Bulacan, now Mayita Biscocho. It was titled “Here Come the Brides–all dressed in native fiber. . .” Mayita had an atelier that specialized in wedding dresses with yards and yards of embroidered, cutwork calado and applique on the fragile handspun native fibers woven of banana and pineapple silk. Something clicked in Chona’s pretty head. This was just the sort of thing that the plantation women might be taught how to do. Weaving had once been a thriving cottage industry in the Philippines, before the cotton mills of Manchester had made superfluous and inefficient the laborious production of the hand-loomed cotton patadyong that every Filipino woman had worn as a workaday skirt or shift. Many of the plantation women were young with good eyesight. There was a purpose and a plan in all this after all. Chona felt inspired. Beauty by Badoy might become a byword yet.

Mayita was pleasantly surprised to have Digna Laon call on her one afternoon with the message that her cousin Chona wanted them both to visit her in San Semilla for a big project. It was a greater surprise to learn that the flighty Chona was now the mayor of her in-laws’ hometown.

“I cannot imagine it either,” Digna shrugged. “We should go just to see how she’s doing. It’s refreshing to take a break in the province now and then. I think the First Madame might even be visiting next week to show the media that things are not as bad in the sugar plantations as the communists want everyone to believe.”

It was a long drive from the airport to San Semilla, so they rested at the Badoy beach house over the weekend. Aunty Meding was there to fuss over them. Mayita experienced a level of comfort and servility that impressed even her, who had grown up having her bottom washed by servants until she was a pre-pubescent adolescent set to enter St. Celestina’s Academy as an interna. The San Semilla staff were diligently obsequious and perpetually smiling, as though nothing pleased them more than to perform menial tasks such as gently plucking the hairs from Digna’s armpits or kneading Mayita’s flaccid abdominals after she had indulged in several helpings of the local sticky rice cakes served with dollops of muscovado, sprinkled with tender grated young coconut and roasted sesame seeds. Erwin was away in Manila, so along with their evening cocktails, Digna and Chona smoked weed. Ever since she had gotten into politics, Chona only did this on weekends or when she had special friends over.

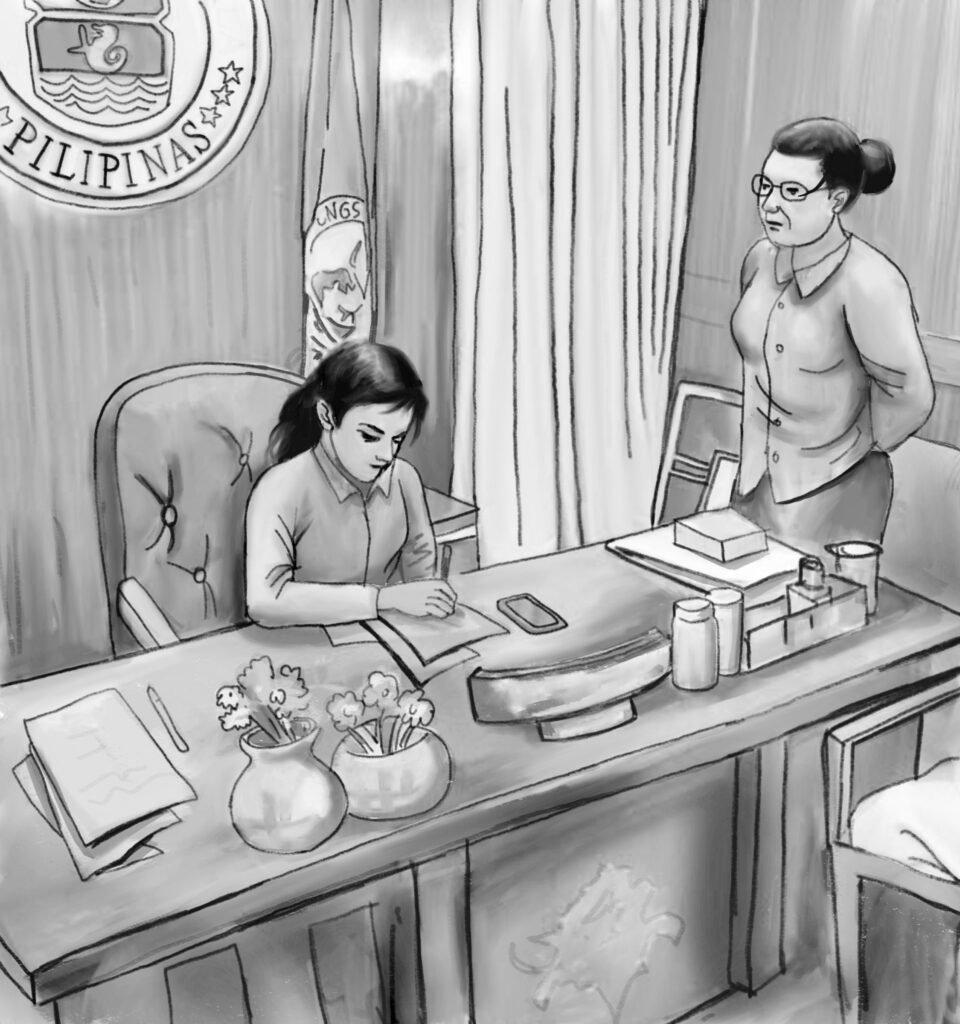

On Monday, Chona took Mayita and Digna to see her office at the municipal hall. They murmured in polite admiration at the decorations of religious artifacts and Chinese trade ware that were worthy of a museum. From the open capiz shell windows, they could see the public market and the quay. The mournful yowling and anguished yelps of several dozen dogs imprisoned in crates, all piled up one on top of the other, floated to them on the sticky breeze. The dumb brutes were mourning their fate as they were to be shipped out to Manila as meat. Aunty Meding ordered the windows shut and the air-conditioning switched on full blast and to muffle the doomed dogs’ cries.

As far as the Laon cousins were concerned, there was too much suffering better ignored, because they could never hope to solve it. Besides, one shouldn’t play favorites, especially not between dogs and people. Even Jesus said that the poor would always be with us and who were they to contradict Him by trying to make a difference. Their mothers, the sisters Teresa Lagrimas Laon and Rebecca Lagrimas Laon, (they had married the Laon brothers Rene and Oscar), demonstrated how this worked, whenever street beggars accosted them for alms. They rolled down their car windows just a tiny crack, then they trilled the same script: “If I give to all of you, what will be left to me? And if I can’t give to all of you, then the ones who don’t receive anything will feel bad. So don’t you see how unfair you are and that you are making me act in an unfair manner as well?”

The Lagrimas Laon sisters had both been local beauty queens and had taught their daughters that there was no better antidote for the blight of poverty than beauty. Filipinas continued to make history by winning international beauty contests, and somehow these achievements must have their equivalent in GDP or other economic measure. Why even NASA had mentioned that Gloria Diaz of the Philippines had just won the Miss Universe title when man first landed on the moon which shows what a milestone that was. The Lagrimas-Laon fixation on physical and outward beauty had been prescient, after all. Secretly, they liked to say that they thought of this even before the First Madame did, but publicly, they gave her full credit for the beauty credo. As loyal citizens of the New Society from the start, and the First Madame’s vociferously dedicated admirers, it was their duty to embody such beauty themselves.

With the hum of the air conditioner and Vivaldi’s “Spring” played over the Mayor’s sound system muffling the captive street dogs’ agony, the three Celestinians, happily reunited, heartily agreed that one should not have to think about beauty in order to get it. It had to be beauty that the masses could comprehend because they must be edified and uplifted by it, which was why each barangay, town, district, and province had its own beauty pageants. Beauty should not be incomprehensible, like abstract art or worse, the so-called installations and happenings that were being perpetrated by the avant garde pretenders in Manila. These somehow involved mind trickery and intellectual sleight of hand. Art should likewise be up front and recognizable like beauty, not suspect and bogus or esoterically obscure.

Aunty Meding peeped into Chona’s office to ask if a delegation of catechists might see her. They were there to complain about jueteng which was beguiling their menfolk to squander their hard-earned pesos on poor chances. Chona distractedly watched their leader, whose name she had promptly forgotten, mouthing words. She was morbidly fascinated by the pouches and wrinkles beneath her eyes, her too light face powder like confectioner’s sugar dustily settled over her caked foundation, and her lipstick and nail polish of coagulated cotton candy pink. She noticed every woman in the delegation had sun-damaged skin. There must be some local herbal remedy for this like a papaya poultice. Every man, woman, and child in San Semilla would be taught how to use sunscreen, even while they were planting, weeding or cutting sugar cane in the fields. The farm laborers in Erwin’s district would have the best skin.

Badoy. . . Baduy. . .Unfortunately, the latter described most of the women who were, as Aunty Meding liked to emphasize, her natural and logical constituency. These were the very women she would have to deal with as Erwin agreed, she must style herself as a champion of women’s causes. This was her sector, a bailiwick that would ultimately propel her to the governorship in the future as soon as her father-in-law was ready to retire, while Erwin would be a senator and perhaps by then their eldest Elijah would be old enough to be the mayor. Erwin made it clear it was her duty to keep such positions warm for their progeny, and out of his brother Dennis’s clutches.

The women catechists’ delegation had brought Chona a present as they had heard she was planning on setting up livelihood projects for the farm women during tiempos muertos. It was a monstrosity of a dried flower arrangement of dyed weeds, surrounded by fake papier maché pebbles and set in a vase of woven drinking straws molded around a clay cooking pot. Their leader pointed out the painstaking if misguided labor that had gone into the project and ingratiatingly asked Digna and Mayita when they were returning to Manila as they might be able to send similar arrangements back with them, but the Manila visitors politely demurred against such excessive largesse. Chona gingerly touched their offering, reflecting that the drinking straws were probably recycled and that the colored weeds came from the fields where animals and men both freely eliminated. Clearly, these poor women had nothing better to do with their time than add to the garbage of the world. She looked meaningfully at Mayita and Digna who rolled their eyes.

Nevertheless, Chona urged them to set the ugly thing on her coffee table, and charmingly explained that she could not have it on her desk as it would block her view of their pretty faces. The women tittered happily and lavishly praised their young lady Mayor’s beauty which was far superior beauty to theirs. Chona graciously accepted this clumsy flattery as her due. Something would have to be terribly wrong if no one remarked how pretty she was looking each day. Before they left, she posed for pictures with them in front of their offering. Then Aunty Meding ushered the women to the conference room where they would be served merienda, and Chona vigorously rubbed alcohol on her hands, following this with moisturizers.

“Sweetie, is every day like this?” Digna wondered. “Let me see your hands. You will need collagen treatments soon. Your veins are starting to show. How can you stand it? Erwin should reward you.” Chona’s eyes turned misty as she thought of all that she endured as a public servant.

There was a diffident but persistent knocking at the door, like a small animal importuning. Aunty Meding was not there to open it, as she joined the women catechists for merienda. The door opened a crack, and Chona recognized the Treasury clerk who had been coming to see her since last week. She could not immediately recall his problem, just that it was annoyingly complex. With him was a middle-aged woman with the drawn look of one who had been sleepless and weeping. Her desperate eyes locked in anguish on Chona’s, who could not help but turn her gaze away.

“Sorry to disturb you, Madame Mayor, but I have brought my aunt Mrs. Halcon just as you said I might last week,” the clerk said with nervous twitching smiles and many half bows. Mrs. Halcon’s lips and cheeks trembled and she whispered a strangled good morning.

Behind the clerk and Mrs. Halcon, pressed a small contingent of uniformed men, a mix of regular army and civilian home defense para-militia, all crowded in her ante room. A grinning soldier peeked through the doorway over Mrs. Halcon’s shoulder.

“Come inside, please,” Chona said which seemed the only thing she could do since Aunty Meding had not returned.

The soldiers and the militia pushed past Mrs. Halcon and the clerk. Mayita and Digna, daintily poised on the cushioned chairs against Chona’s desk, stared in perplexity and drew back. Two of the men held a young girl firmly by her armpits, while Mrs. Halcon stood behind her, clasping her shoulder and stroking her hair. The girl’s head was bowed, and her shoulders heaved with muffled sobs.

“Good morning, Madame Mayor Badoy: Sgt. Imbudo at your service, Ma’am,” snapped a short stocky soldier with a broad flat nose and aubergine lips, who appeared to be their leader. The Treasury clerk scurried to his side and explained the motley delegation’s presence to Madame Mayor in eager but broken English.

“Madame Mayor, this is the sister of Diego Halcon, the one who is working now at the Barangay Health Center. Please remember he was amnestied before because he is not a real communist, so he was employed there but only as contractual. But there are those still not believing he has transformed and turned over a new leaf. You know, Madame Mayor—always there is so many intrigues. Maybe someone else wants Diego’s position. So now his sister who is also my cousin is detained because they say she is a member of the NPA, or New People’s Army. Diego went to you last week and yesterday, Ma’am, to ask if you are helping for his sister to be released. She’s knowing nothing about the movement but is just a former student and the youngest and only girl in their family. He saying they are using his sister to force him to tell what he knows about the others in the movement but he is not knowing anything also because he is not with them ever since.”

“Where is this Diego Halcon now as it seems this concerns him in the first place?” Chona asked, pleased to show she had been listening. “Is he absent?”

“No, Madam Mayor. He have done something for the Health Office so he gone to San Dionisio proper very early this morning. He’s only contractual and knows he cannot be absent. It’s like an emergency, Ma’am, because there’s flash flood and mini mudslide so they sent Diego to brought relief goods for the evacuation victims.”

“Well, he shouldn’t be absent. Jobs are very hard to come by these days,” Chona Laon Badoy, who had never had a real job in her life, virtuously declared. “Anyway, in the spirit of reconciliation, I suppose everyone deserves a second chance even if he used to be an NPA.”

“He is not an NPA and he is not absent, Ma’am,” the clerk repeated with quiet insistence. “He’s just on special assignment because of the state of calamity.”

“What is this case about again?” Chona motioned impatiently. “You know I have several appointments for today. We have guests here from Manila who will help San Semilla with income-generating livelihood projects so we can have progress for all. We still have to visit the weavers in Barangay Timawa.”

“Please, Madam Mayor, it is a case of mistaken identity. They say she is a student activist. My daughter is not even studying now because we have no money for her matriculation. My husband cannot work anymore, Ma’am. He had a stroke and now, this. . .” Mrs. Halcon’s voice in a mix of Hiligaynon and Kinaray-a trembled and trailed off helplessly.

“What mistaken identity?” Sgt. Imbudo chuckled. “We have our intelligence sources. You are questioning our methods and our capabilities.”

“Inday,” Mrs. Halcon loudly whispered in her daughter’s ear. “Tell Madame Mayor that you are innocent. Tell her it is all a mistake.”

For the first time, the girl raised her head and the three Celestinians were uniformly stunned at the delicacy of her features, at how luminous her dark eyes were and how perfectly shaped were her nose and brows. Even in her disheveled state, her youthful beauty shone through, turning the Celestinians’s expensively cultivated, lasered and contrived perfection to shoddy attempts at counterfeiting nature’s mastery. It was as though the clouds had parted and the light of the sun now showed things for what they really were. Chona Laon Badoy stared at the young prisoner sullenly, hating her without realizing the vehemence of her feelings. Her impeccably manicured fingers unconsciously clenched and unclenched on the sheaf of papers that Sgt. Imbudo had laid upon her desk.

The vision of this young girl’s unspoiled beauty made her realize why her brother-in-law Dennis, and perhaps even her husband were said to periodically take their four wheeled drive vehicles to the remotest barrios and farms, searching for such rare combinations of natural pulchritude: the rare generative fruits of the libidinous adventures of Chinese traders, Moorish pirates, Spanish friars, and even American riflemen crossbred with native Indo-Malay and Pacific Islander stock. The girl bore an uncanny resemblance to the mistress of one of the Badoy family friends, a popular race car driver. He had plucked his treasure, then just a fourteen-year-old barrio lass past puberty, from one of the mountain communities near San Semilla and had kept her well hidden away in Manila from his wife and his seven daughters who were all Celestinians themselves. Aside from initiating her in the pleasures of his bed, he had sent her to high school, always chaperoned, in a Manila university which his family owned. Over the years, the girl had blossomed and by the time she was nineteen, she was polished enough to win a national beauty contest title and went on to become the first runner-up in an Asian pageant. By then, the racer had released her and she then moved on to another protector. She now lived in San Francisco as the pampered mistress of an Indonesian oil man.

As the Celestinians stonily stared at her, the girl’s full-lashed eyes brimmed with tears and her whole body quivered. Her dew-touched lips parted and she spoke softly in the Kinaray-a dialect of the mountain towns.

“What’s this? I thought she is a college student. Tell her to speak in English or even in Filipino or Hiligaynon. I don’t understand a word she is saying.”

The girl suddenly wailed and heaved. Broken phrases tumbled out about being made to dance the cha-cha naked, and about her mother not being allowed to see her until today, and pleas to the Mayor to be allowed to go home with her mother. Chona busied herself with leafing through the folder that was supposed to be about this particular prisoner.

“But what about your involvement with the New People’s Army as the reports state? You know our people are very careful about these things. They do not go around just picking up innocent people on a whim,” Chona frowned at the Treasury clerk and thrust a box of Kleenex at him. “Give her some tissues please and tell her to control herself. She’s making such a mess.”

The weeping mother dabbed at both hers and her daughter’s faces. The girl defiantly shook her head muttering that these were all lies.

“Apologize, just apologize,” her mother begged. “Ask for mercy from the Madame Mayor so I can take you home.”

“What is this about your training to be an operative of the NPA youth in the schools? Are you out to recruit more communists, hija? Don’t you think we have enough problems as a nation? We need unity, not division. You should stop making it worse and try to be part of the solution instead.”

The soldiers nodded and there was a chorus of agreement as they tried to cajole the girl to stop weeping. She only grew more agitated and gasped brokenly about her having human rights.

“Naku! Are you threatening our Mayor, our Congressman’s wife with violating your human rights after she agreed to see you like this? You should be ashamed,” shrilled Aunty Meding, who had finally returned.

“It’s all right. It takes more than threats to scare me. But what I don’t understand is what am I supposed to do with her? I don’t think this is under the jurisdiction of the Mayor’s Office as this is a matter of national security–and she’s not helping any, incoherent as she is. I can’t even understand what she’s saying. Where is her lawyer?”

The clerk stammered something about his cousin’s volunteer lawyer having been called to Bacolod on another emergency as well.

“Ay-yay-yay—not another communist client?” Chona sighed. “How they keep multiplying! We have to follow the proper procedure on these matters. After all we are three separate but equal branches of government and even, I don’t want to go beyond my jurisdiction. I don’t want to overstep my boundaries. I think we should just wait for her lawyer to handle this.” She quite liked the sound of that. It was always good to have lawyers present to make things seem legal.

“Please, Madame Mayor. Let me take her home and we will report to the station commander or to your office every day so that you can see that my daughter is doing nothing wrong. She is innocent. It is all a mistake.” Mrs. Halcon suddenly cried, her arms wrapped tightly around her daughter.

“No need to shout, Tia’y. This is not the plaza or the market. This is the Mayor’s office,” Aunty Meding interjected.

“At any rate, I don’t think I can do anything without proper legal advice,” and pleased with her even-handedness and cool professionalism, Chona indicated that the audience was over.

Realizing that this was it for her, the girl threw herself upon the carpeted floor between Mayita and Digna, and desperately clutched at the delicate legs of Chona’s Queen Ann escritoire. Many pairs of strong arms roughly pulled her back, dragging the desk along with her while her wailing mother tried to shield her with her own frail body. Chona and Aunty Meding screamed that the things on her desk would fall and break, while the mother and her daughter both wept and shrieked even louder, begging that the girl not be taken back to the stockade, or for her mother to be allowed to stay with her.

“Ay, que scandalosa—a real Amazon, this one!” Aunty Meding cried out, disapprovingly. Mayita and Digna scrambled out of their chairs while the soldiers surrounded the girl and her mother. They pried her fingers off the furniture and roughly threw her mother aside. The girl tensed her thighs and dug her heels into the carpet but they were just too many and too strong for her. They actually laughed, and taking Aunty Meding’s cue, raucously called her their Kinaray-a Amazona. Her helplessness invigorated their masculine superiority. The girl’s strength was nearly spent and her voice was barely audible, the merest whimper. Someone said she was also a pot head and that it served her right. She was carried away in an ugly parody of those writhing bodies flinging themselves into mosh pits at rock concerts while her anguished mother scurried after her. The clerk who had accompanied them bowed and apologized and followed them.

“Too heavy,” Digna sighed, her eyes large with wonder. “Too much drama. Sweetie, I could never do this. I am so proud of you.” And she embraced her cousin.

“I suppose it is part of the job of being a public servant,” Chona replied.

Aunty Meding confirmed that the First Madame would be flying in later or perhaps tomorrow in a helicopter. They would show her how truly benign conditions were in the sugar plantations. Mayita was pleased that she would be meeting the First Madame under such auspicious circumstances and that she had brought several samples of evening purses and wraps, fashioned from native fabrics or embroidered in Filipino motifs of anahaw leaves and sampaguita blossoms. She would gift the First Madame with whichever pleased her. She had met her before but now, she would have the chance to make an impression upon her. It was wonderful what marvels the right connections might lead to. They would lunch on the golf course, then wait for the First Madame to arrive. Mayita would be introduced as the schoolmate of the Laon cousins from the prestigious St. Celestina’s Academy and a niece through marriage of Flory Ting whose husband Larry had a virtual monopoly on port services. Her handicrafts samples wo.uld shine as a beacon for the hapless women during the darkness of the tiempos muertos. It was fated. How could she go wrong? It was wonderful to be with the right people. After all, it was whom you knew that really mattered.