I’ll begin with a crude reduction of La Bruyere’s opening paragraph from Les Characteres: Nothing here is meant to be the first of its kind. This thing itself is a pale and conflated imitation of what I found most resonant in the aphorisms of Cioran, but I shall persist. I believe I still have much to say in regard to the things I’ve said before, and they must be said in the following manner.

I read Seneca’s letters to Lucilius at the height of the lockdown. In those months, I was drawn to the Stoics. But then who wasn’t? I have reasons to believe that all of us, in one way or another, became Seneca’s disciples simply by virtue of persisting—or even just existing—through the worst of those times.

How dreadful is it for the body to refuse to sink into sleep when it needs rest the most? Cioran himself agonized about his insomnia. In my case, at four in the morning, I find myself awake. I didn’t want to be. Why does our body betray us so? Or was it our brains? Does it not possess the will to lead itself to the very things it needs to sustain itself and the shell that it unfortunately finds itself within? Choked by the grasp of sleeplessness, I remove myself from the bed and begin to stare at the little I’ve stashed on my shelf of food. Sometimes, there’d be bags of chips, cans of sardines or small packs of biscuits of which the only value was the sugar they were made of. I’d be so disgusted by them that I’d pick up the phone and order something with so much grease. By five, I’d be stuffed as a spring roll about to burst. By six, as the sun starts to frighten the dark away, I’d be back in bed, satiated and nauseated by the amount of fat I had consumed. How unfortunate it is that the things that bring us comfort in life are the very things that bring us closer to the inevitable.

A friend once took me to a screening of The Substance (2024). He sent me a link to the trailer of the film beforehand, but for some godforsaken reason I had failed to view it. I walked into the theater completely blind to the film’s content, except for the fact that it belonged to the “body horror” genre, as he told me that same day. By the final act of the film, a couple had stood and walked out of the theater, and I was glaring at the friend. As the end credits rolled, I expressed emphatically my hatred of him and the film. It had upset me to the point that to try to wash off the unpleasant taste it left in our mouths, we agreed to go to a bar in Ortigas and forget the whole thing for a while. At the bar, we befriended a cinephile who’d later claim to have liked the film. To my surprise, as months passed, I found myself agreeing with the man and my friend’s assessment of the film. It took me a while, but I finally saw its merits, looking past the gore and the sick-inducing sound.

It’s been a year since Dan and I had fallen apart. There were tears involved the night we ironed out the whole thing, and we unfollowed each other thereafter on our respective online accounts. I had since gone out on dinners with other men, and I had no reason to suppose that he did otherwise. And yet, despite the year that came and went, I still found myself thinking of him. Not because I craved to recover what was lost between us, but because without him, there’d be no me to look back at all those months at all. I owe him, quite literally, this body and its craving to remember.

At the check-out of a grocery, the woman behind the register asked if I had a bag for the things I’d bought. I looked into my cart and realized that, though I had intended to bring one before heading out, I had ultimately failed to do so. While walking out of the store, I tried to balance in each arm a loaded paper bag threatening to spill its guts all over the road long before I’d reached a tricycle terminal. That, I suppose, is the worst a faulty memory can do.

There were nights at the gym when the weight I had but little trouble lifting days before suddenly seemed like the Excalibur. I’d wonder if it had to do with it being late and if I had a better chance to be stronger while the sun was up and in the company of more people at the facility. For a while, the dumbbell rack would return my stare and seem to beckon for me to give up. In a way, I would. But not entirely. I’d amble off the bench, return what I was trying to curl, and resolve to settle with a lighter weight. With this, I still was able to do what I went there for, though in a way that convinced me to refrain from doing things too late in the day and to give my arms the rest they needed.

The passage of time does not obliterate the sadness brought by the passage of years. As the clock struck twelve, I found myself watching the distant fireworks by the sink at the end of the hallway of my new home. Downstairs, the house attendant and his family were greeting each other with a “Happy New Year!” Before me, the windows were closed. I could see through the glass pane—overlaid like a mirage on the night sky blooming with firelight—an image of myself, hands clasped behind my back, eyes swollen from weeping and sleeplessness. But I had wept less and for just a few minutes. So, while the sadness sitting on my shoulders like an unwanted companion had not completely disappeared, it didn’t remain as humongous as it had the year before.

I confess that at times I thought of quitting my job to fully commit to being a writer. “Like Doris Lessing,” I told a friend. He reminded me, however, how she had the privilege of doing so, being herself “a white British woman.” In retort, I said I couldn’t always be a victim. I said “I’ll find my ‘privilege’ then.”

I’ve yet to read The Grass is Singing, the novel Doris Lessing published after quitting her job. But I’ve read The Golden Notebook and Memoirs of a Survivor. Those works blew me away, and I couldn’t help but wonder whether or not she would’ve written them had she not had the freedom to extricate herself from a day job and polish her first book. Sometimes, I think of being involved with a rich man who would feed me as I finish my first novel. In fact, I had come close to doing so, having met this corporate manager almost four years my senior, who replied in the affirmative when I asked about the prospect of him supporting me. I did consider getting back to him. But then in the couple of times we’ve met I noticed how when he opened his mouth to speak the smell of dead fish seemed to waft in the air between us. I had no personal vendetta against people afflicted with halitosis, as most of us could be susceptible to it in the times when our grueling lives trump the need to tend to hygiene. I was also drawn to the man’s kindness, intelligence, and ability to banter when I have things to say about art or the drudgery of life. When I imagined, however, a life where I’d need to face him and his mouth on a daily basis, a part of my brain instantly recoiled. It struck me then that I was yet to be ready to face the daily smell of dead fish to fully commit to my chosen art.

I was told never to tell this story. When I was in high school, one morning, the woman took me aside on a gutter close to our house to talk to someone through her phone. This happened so long ago that I have no clue what the stranger and I had to say to each other. All I now remember is that the voice did not belong to the man who fed and raised me. The woman gave no introductions. She had just said, “Halika, anak, may gusto kumausap sa ’yo,” and I held the phone to my ear, partly out of this morbid curiosity about this person she had been speaking with for the past two days when the man of the house was out for work. Much later in the afternoon, the woman told me the stranger on the phone was my “real” father. Imagine that. To be told, after fourteen years, that I wasn’t my father’s son. I was not in the least disturbed. I was amused, actually. A few days had to pass before the woman managed to schedule a Skype call with the “real father.” When it happened, I didn’t feel anything. He promised to buy me a brand-new laptop during the call. However, weeks after that call, the woman told me he had ceased sending any messages. I can sense that beneath the offhand remark was a painful disappointment. When much later she asked if I was bothered about the revelation, I told her the truth: “I’m only sad he couldn’t give the laptop he promised.” She seemed satisfied with the answer. Then she told me never to tell this story to others. But more than a decade had now passed since that strange phone call, and I wasn’t at all tied to the woman or the house or the man who had fed me. The things that happened within those years reduced the mild surprise at the revelation to nothing. The stranger I spoke with through the woman’s phone had returned to being what he was before my awareness of his existence: Nothing. I’d sometimes think how he was doing and promptly stop myself. If he couldn’t be bothered to send a laptop—or even a message—to the woman he had impregnated almost half a century before, what is it to me if he is or isn’t alive? I had lived with a complete set of parents before, but I had to leave them to save myself. What need do I have for another one?

While with all my invocations of Cioran I may appear to revere him so, I, in fact, loathe what he had to say. Granted, his shards of truth and gloom are cutting and sharp. But are they worth the wound?

In the endnotes of his translation of Six Records of a Floating Life, Leonard Pratt remarked how the description of the lock wounding around the neck of the prostitutes—observed by Shen Fu in one of the boats he visited with a friend—may not be as “sinister” as it seems. He remarked how the accessory had something to do with luck. With securing fortune. Hundreds of years after the “six records” were written, “chokers” were still in fashion. I don’t have one. Having thought about it, I myself never had a sense of fashion. The man who raised me once drove the entire family to a church in Antipolo, where he bought us necklaces that he had the priest bless with holy water. Despite the uncertainties I had about my Catholic faith, I bore the cross on my neck for some time, more as an attempt to break the plainness of my appearance than a brazen interpretation of what happened in Golgotha. I’d pair it with a sleeveless shirt and a baseball cap with the visor turned to the back. It was what I supposed back then a “fashion” statement—which I soon tired of. The cross went to a box and was never retrieved again. The man had also bought all the watches that ever wound around my wrist, and when they were in need of repair, he’d be the one to take them to a watchmaker’s stall in a nearby mall. When I moved out of the house, I had on my wrist a watch whose straps the man had gotten replaced with leather ones—as he noticed how I kept breaking the silver one it came with when it was first bought. The hands of this watch had long stopped ticking. It is now kept in another box, in my new home, far out from my previous home. By now, I have long been stripped of all the things I was given by the people who raised me. I now imagine myself as an ancient whore—freed from the lock that made his fortunes possible.

The power of words. Of all the things she did, it was the words that proved to be more consequential even to this day. She had slapped me so many times that my face was swollen and red. Her fingers had pinched my thighs; they carried bruises for days. She had hit me with a broom or a belt or whatever her hands could clutch at that moment. One time, she even hurled a massive wooden stool at where I stood, trembling. All these she did when I was but a powerless child and all were enough to engorge the hate I have carried to this day of myself. None, however, had ever been as scarring as the words. No one else had told me all the curses I’ve ever known in our language. No one else had told me that my death could be easily gotten over. No one else had wished for me to be another person, another child. Through her words, I learned how devoid I am of purpose—how repulsive, replaceable, and unworthy I am of life. Her words and the way they were said carried so much power that attempting to produce them on this page would set me up for failure: I cannot make any reader feel the coldness and terror and aching to be free from the woman’s clutches. I cannot make the reader feel the horror when she once told me—in one of her lucid moments after leaving my body with welts and bruises—that she did all that because “I love you.”

“And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth; both man, and beast, and the creeping thing, and the fowls of the air; for it repenteth me that I have made them.” – Genesis Chapter 6:7.

I am to an extent the incarnate of Erika Kohut. Like her, I pine to submit to people with a taste for a certain level of violence. This should explain why, when told to wring a man’s neck in bed, I’d fail in my attempt. There is no vice versa. I must be the one to lose his breath, just like I almost did as a child and as I had always pined for as a grown man.

There’s a reason why people subservient to power lose their sense of self, humanity or the distinction between themselves and the objects around them. The woman’s love—like that of the God of the Old Testament, the Earth, or the mother in The Piano Teacher—had such a force that it annihilates the things it forced into being.

I once became involved with a poet who gave me a canvas bag with his oil painting on one side as a birthday gift. The painting was of a faceless man sitting on what looked like bamboo shoots, the sun rising behind his head. The poet lived in Makati. Once, when he was sick, and I couldn’t travel from my place in Maginhawa to his, I had a bowl of ramen delivered to his place. The soup base was thickened by squid ink. By then, I was still doing my best to be the good lover that I had failed to be in my previous relationships. I intended for the bowl of soup to keep him warm and help him recover. Instead, he began to have an itchy throat and skin. Later on, he reminded me how he was allergic to seafood—a fact that I forgot as I had begun selecting for his food through the phone. I was ridden with guilt. All I wanted was to help him, and here I was, worsening his condition. I apologized profusely, wanting so much to sock myself. But kindness remains to be the very thing that keeps the world more bearable. Despite the mistakes, the stupidity. “It’s okay, baby,” he had said. He said he had enjoyed it, and he chose to finish the whole thing because it was good. He was simply placating me, perhaps downplaying the fact that I almost endangered his life. But I believe he cared enough for me to shield me from my own misguided attempts at loving.

This happened when I was employed by the university. One day, when I went to a nearby bank to use the ATM, I found that the previous person had not retrieved the receipt the machine had printed. It showed the amount the person withdrew as well as the money left in his account. Forty thousand pesos. Seeing the numbers filled me with awe, especially since at that time, I was intending to have a few hundred pesos to get me through the week—just enough not to hit the three-hundred-peso minimum balance my card required. I finished my own transaction. While walking from the bank, I noticed that I had been holding on to the receipt left by the previous person. I didn’t know why, but I suddenly found myself folding the square white paper and tucking it inside my wallet. In the weeks and months that followed, I’d sometimes look at that receipt. It isn’t mine but I kept it. Staring at the numbers, I’d tell myself: one day, one day.

For a time, I trained new hires for a BPO company. The promotion from being an agent didn’t bring the sort of comfort that would’ve spared me from having to wait in queue for tricycles or chase jeepneys along the “killer highway,” Commonwealth Avenue. The salary increase—just enough to add a few more kilos of meat and rice to the family’s stash in the food pantry—was not in any way sufficient for the loan required to have a car of my own. So, in the mornings, I’d find myself on the road, in my long-sleeved button-up, a bag slung on my back weighed down by the company-provided laptop. This laptop was ancient. But I did my best with it despite the slow processor and the glitches. I created PowerPoint slides with it, which I used for my training with the new hires. At times when I had much to do, I’d take the thing back home and continue the work in the time I was given to rest beyond the office. I’d bring the thing despite the chance of rain. And when it did rain, I’d slump the bag before my chest, hug the thing as the raindrops pelted everyone on Commonwealth Ave. There’d be so many people waiting for the vans, the jeepneys or even the ride-hailing apps. Those apps by then were beyond my means. Why would I pay beyond two hundred pesos to cross the same distance I could at under twenty pesos? The comfort, perhaps? Comfort has a price. A price I’m yet to be willing to pay or have the means to pay for. And in those days comfort was the least of my worries. All I thought as I stood on the sidewalk in front of the building where I worked—stood and ran, like the other workers who had just exited their respective buildings—was that I simply wanted to go home. At times I was lucky. At times, I was not, and I’d have to chase a jeepney and hang at the back like the other men. I’d hang at the back while in my office attire, weighed by the ancient laptop. I’d hang at the back despite the smoke, the rain, and the risk of falling and being smeared on the road by the wheels of a truck speeding behind us.

It’s always a wonder how the same thing could be understood so differently by different people. Some might have rightly seen the fact that I had to risk my life just to get home as symptomatic of a nation’s failure to fix its transport system. Others would emphasize the absurdity of my life decisions. As for myself, and especially at that time, I saw it as another part of another day. While I saw how changes must be done, I also understood the things that I can do in the meantime. Much of it, at the end of the day, had a lot to do with the simple yet rebellious act of surviving. Of waking up tomorrow and all the days that I will myself to do so.

On the way to a friend who lived in Mandaluyong, I had to take the MRT. As I am from the North, I have to cross a bridge at the North Ave. station to get to the southbound trains, a concrete bridge that late in the night wasn’t usually jammed with commuters. As I was crossing this bridge, I noticed how at one point near the stairs that led down to the ticketing booths, the crowd had stopped moving. When I looked, I saw a cop stalling at the end of the line. Moments later, there were screams from men. They belonged to other cops, who turned out to have been chasing another man on the bridge. This man later appeared to the right of the crowd, the part trodden by those who were to ride the northbound train, which by then was cordoned off. The man apparently was a thief. The cops who yelled were trying to stop him, their guns out in the air. Their deep-throated screams bounded off the concrete walls of the bridge and filled my chest with unbearable dread, making me think of guns being fired and stray bullets flying everywhere. It was fortunate that the crowd had begun moving again, in panic. The skirmish inspired so much fear there was a troubled din that echoed all the way to the ticketing booths. The crowd came so close to trampling. If I had the space, I would’ve run myself. But I couldn’t. I was at the mercy of the crowd. It may have been luck that I got to my friend in one piece and without a hole in my head that wasn’t supposed to be there. It may have been luck that the only scar I had was the thought that I could at any time be gone without any careful planning. That I could at one point be crossing a concrete bridge to meet an acquaintance, and then in the blink of an eye be waiting for Charon and his boat to cross the river Styx.

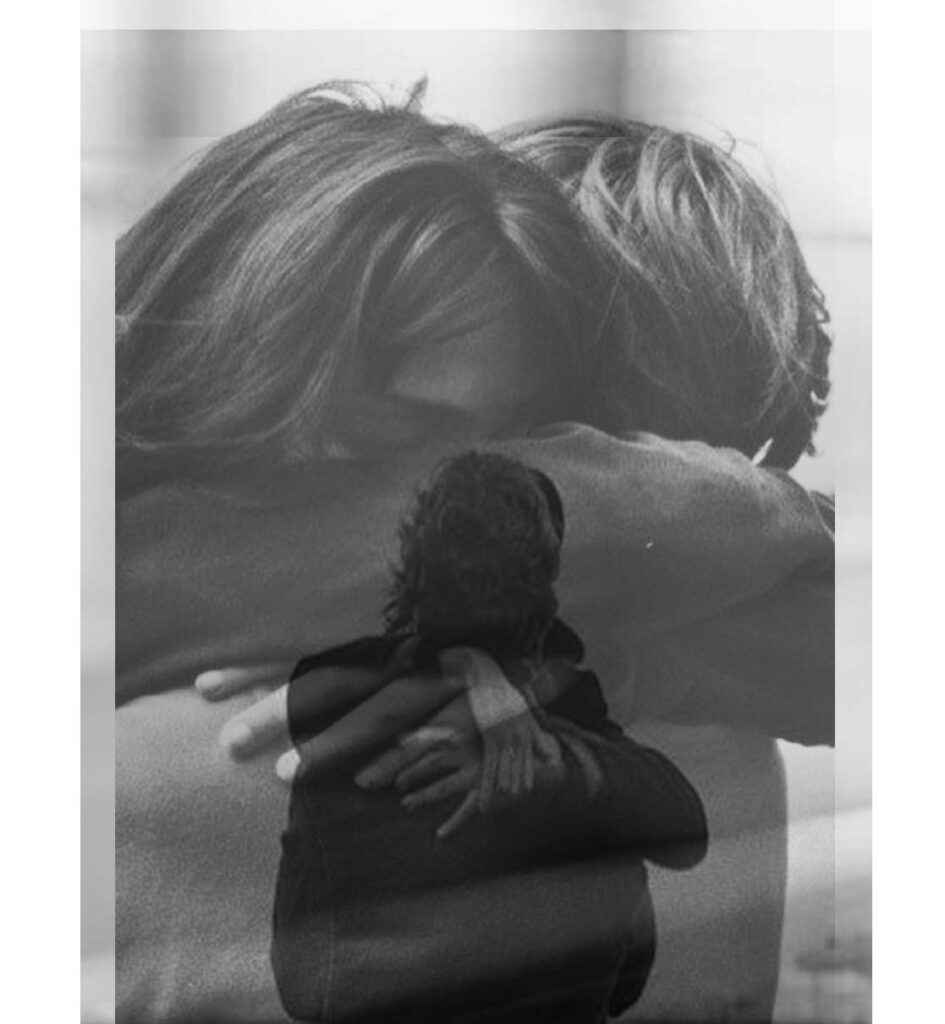

I saw him again tonight. Dan. I was in a tricycle, fresh out of the gym, heading to a Savemore grocery store. I meant to have a quick trip to the grocery as I ran out of rice and soap for the dirty dishes. There was light traffic on the road, and the slowness of the vehicle afforded me a generous view of the side streets of Maginhawa. And then, all of a sudden, there he was: a familiar face walking in the opposite direction, close to the pavement. He was in a running apparel. Black shorts and cap and T-shirt, trainers as white as they perhaps had been when they were first bought. With a trembling voice, I told the driver to stop and to let me off. My hands shook as I fumbled for the fare, feeling embarrassed while the man watched as I dug into my purse. A full minute might have elapsed before I managed to retrieve the right amount. Then, having handed the fare, I scanned the road. My heart was racing. I was afraid that he had been a mirage. That I had simply imagined him among the parked cars and evening pedestrians. I traced the path I imagined he took and was relieved to see his silhouette on the other side of the road, set against the lights of a crimson building whose first floor was a 7-Eleven. I looked from left to right. I made sure to be on a zebra lane, that I wouldn’t be hit by a passing car, that I’d be alive just long enough to cross that distance between us. He kept on walking. He had his earbuds on, unaware that someone from his past was aching to reach him. I crossed the road without dying. In my head I was rehearsing the things I was to tell him, the ways to draw his attention without scaring him off. More than a year, after all, had passed since we last saw each other. In the end, I decided to catch up and simply walk beside him. When I did this, he turned to me, and it took him a few seconds to realize who I was. “Long time,” I said. He looked surprised. He looked just like he had before: athletic, well-dressed, intelligence shining behind his glasses. I couldn’t help it. My insides felt like a laundromat, and all sorts of feelings and words tumbled inside it, aching to be freed. “Can I,” I finally asked, “Can I hug you?” He nodded with a smile. That smile. My vision blurred with tears. I embraced him, and he returned the gesture, with much intensity. I was taken back to that first night that the shape of his body became first familiar to my own. I had so much to say. Apologies, gratitude, regret. And yet, we just stood there, arms around each other. He had just been in time when he found me at that hotel in Cubao, when I was drunk and intending to swallow some pills. But he found me. And I found him now, there on a side street. I was there because of him. Here, because of him.

Near the end of Shen Fu’s Records, my mind kept drifting off. He was writing about the many travels he had with friends—the bodies of water, tracts of land, satiating food, and all the walking he did among so many beautiful sights. Deep into his details of temples and pavilions, I became entrenched in this desire to see the world beyond the home I’ve made on Maginhawa. I thought of returning to Dumaguete—the first place I rode a plane for almost a decade ago. I thought of the waters and its seawall, the peaceful silence of its streets, the friends I met, and the sweet silvanas we shared. I think of my life and of the world—and how much I want to see more of it.

He was to have a haircut. I asked if I could walk him on the way, and he said yes. While walking on the bustling street, we kept asking the other, “How have you been?”—then giving out impassioned reassurances that we had been doing alright. He had gone back to teaching in the university. When he asked if I was doing the same freelance work, I said yes. He said he had been seeing my posts on the Internet. The photos I’ve uploaded to the only social media account I’ve kept, Instagram. He was happy that I seemed to be happy. Then he said he was seeing someone now, and he had been telling this person about me. How happy he was for me. Near the barbershop where he was to have his haircut, he said, “I missed you.” He has a flight to Vietnam later at midnight. He sounded excited, thrilled for his first solo trip overseas. We embraced, again. The two of us took a photo. I told him, “I missed you, too.” Never in my life have I thought that I’d miss someone as severely as that.

Fragment by fragment, I’ve tried to build a case against my understanding of Cioran. Against Ligotti’s views in The Conspiracy Against the Human Race. Against what Houllebecq purported that Lovecraft had written about in Against the World, Against Life. But, alas, I realized my efforts may be inept. I am as unequipped as I was when I took that Aquinas class back in my postgrad years. At this point, I am tempted to concede that I didn’t have the right words to counter the force of their well-versed plaints against life or even human consciousness. This admission, however, isn’t an act of surrender. Because I have one remaining argument to make: the argument of my very life. The fact that I am here, still, writing and thinking and remembering. If I’m allowed to be a part of all these thinkers’ conversations, I wouldn’t just offer an echo of Camus, Seneca or any other stoic. I’ll instead present these shards of memory. For I’ll keep them, these thoughts and recollections, however jagged they are. However much they fail to cohere and tend to meander. However much I’ve bled for their sake, these pieces have made me the person that I am. In all its pain and darkness and absurdity—or perhaps because of these very things—I found that living remains a worthwhile task.

I couldn’t help but turn to watch as he ascended the stairs to the barbershop. He had said he was happy that I was happy. I had so much to say about this happiness: my thoughts, my words, and my recent history. But he went on climbing the staircase until he vanished from my view. By then, I was gripped with longing—to thank him again for this gift of a continued history—with all its fragments, its foolishness, and its endless search for meaning.