In the year 1950, my village knew little of the Cold War although its geopolitical tremors reached even our mountains. The Philippine national government, backed by the Americans, was locked in a struggle against the Huk rebellion for control of Central Luzon’s mountain territories.

My village refused to pay taxes and be ruled by a government that did nothing to serve us, so we supported the Huks. But the more superstitious villagers renounced their allegiance when some men claimed to have spotted an aswang, an organ-devouring monster. My older brother Ramil and I saw her, too—a black-winged creature flying over the mountainside, prophesying the death of anyone who aided the rebels.

Two days later, a rebel soldier was found dead on the road, his body shriveled with two puncture wounds on his neck. That warm afternoon, after laboring in the rice fields, Ramil and I entered a bamboo house eatery where the villagers often gathered to eat and drink.

“Ramil and Enrique, come join us,” called the loudest of the patrons, who wiped his hands on his shirt that stretched tightly on his bulging belly.

Around his table, his peers greeted us and offered to share their beer, pork sisig, and rice. I knew them as gossips, always listening to the latest rumors, and were the first to spread news of the aswang sightings.

My brother and I declined their invitation. Neither of us wanted to linger, especially Ramil who claimed he had something to do before evening, maybe Huk activities. Ramil, like many young men of our age, was a Huk fighting for the freedom of the mountain territories.

After ordering our own beers and snacks, we settled at a smaller table. Ramil set aside his rifle, leaning it against the wall. Firearms had become a common sight since nearly every Huk had one.

“It’s an aswang,” Ramil said, eager to voice his opinion. “She’s tired of my comrades hiding in her woods and has started hunting us.”

“We can’t be sure. She flew too high for anyone to get a clear look,” I replied. Unlike my brother, I had the privilege of studying under Catholic missionaries. They taught me to denounce violence, so I took no part in the rebellion. And I learned to be skeptical of my village’s superstitions. “Her voice didn’t sound natural. It was too rigid.”

“Of course she keeps her appearance hidden and has an unnatural voice. She’s a monster with witchcraft.”

I bit into my rice cake, deep in thought. An aswang was an evil female creature who devoured organs and the fetuses of pregnant women. She could take many forms—a hound, a ghoul, or a winged woman without legs, her entrails dangling from her waist. “But her kill method is wrong. Aswangs eat organs, and our exsanguinated victim wasn’t missing any.”

“Maybe she wasn’t hungry. Maybe she just hates us.” Ramil picked up his rifle and stood. “We have to kill her first.”

“What are you going to do?” I asked, following him.

“The errand I told you about,” he replied. “I’m going to hunt her. We can’t let her stray this close to my comrades and our village.”

“Wait for me.” I strapped my bolo knife to my belt, grabbed a bag containing my hiking gear, and followed him. Something about this felt wrong, but I knew I couldn’t convince my brother to abandon the hunt.

We went on foot, familiar with these mountains since our childhood. Our surroundings were mostly jungle, but there were dirt trails for hiking and some wide enough for vehicles. When we reached the road where the victim had been found, we searched for the aswang, keeping our eyes on the sky and treetops to catch a glimpse of her black wings.

As the sun set, I dug into my bag for my flashlight and switched it on. We roamed the trail, every rustle in the woods making me shudder. As twilight passed, my hands trembled, jerking the flashlight beam from side to side. I no longer wanted to find her. I prayed she wouldn’t find us. I told my brother I was scared and wanted to go home.

“We can hunt again tomorrow.” Ramil slung his rifle over his shoulder and took my flashlight from my shaking hands. “A rifle’s no good in the dark anyway. You watch my back in case the aswang comes our way.”

We marched on, passing houses overlooking rice fields, then reached a dark road between dense trees. Suddenly, a cackling voice, as loud as a car engine, boomed through the trees. “Whoever aids those rebels who trespass in my domain, I curse you and your family! Sickness and death will come to you!”

The words sent chills down my spine. Hearing any voice in the woods at night would. It was the same voice we had heard two days ago when the black-winged creature flew over us—exactly the same tone as if it were a recording playing from a radio.

Ramil held the flashlight in his mouth and reached for his rifle.

A spotlight suddenly illuminated Ramil. As he turned, flashes of light filled the road and muffled gunshots whizzed past me. I covered my mouth and dove into the bushes as my brother let out a scream but was quickly silenced. When I turned back, the flashlight he carried lay on the ground, its flickering bulb illuminating Ramil’s lifeless body damp with blood.

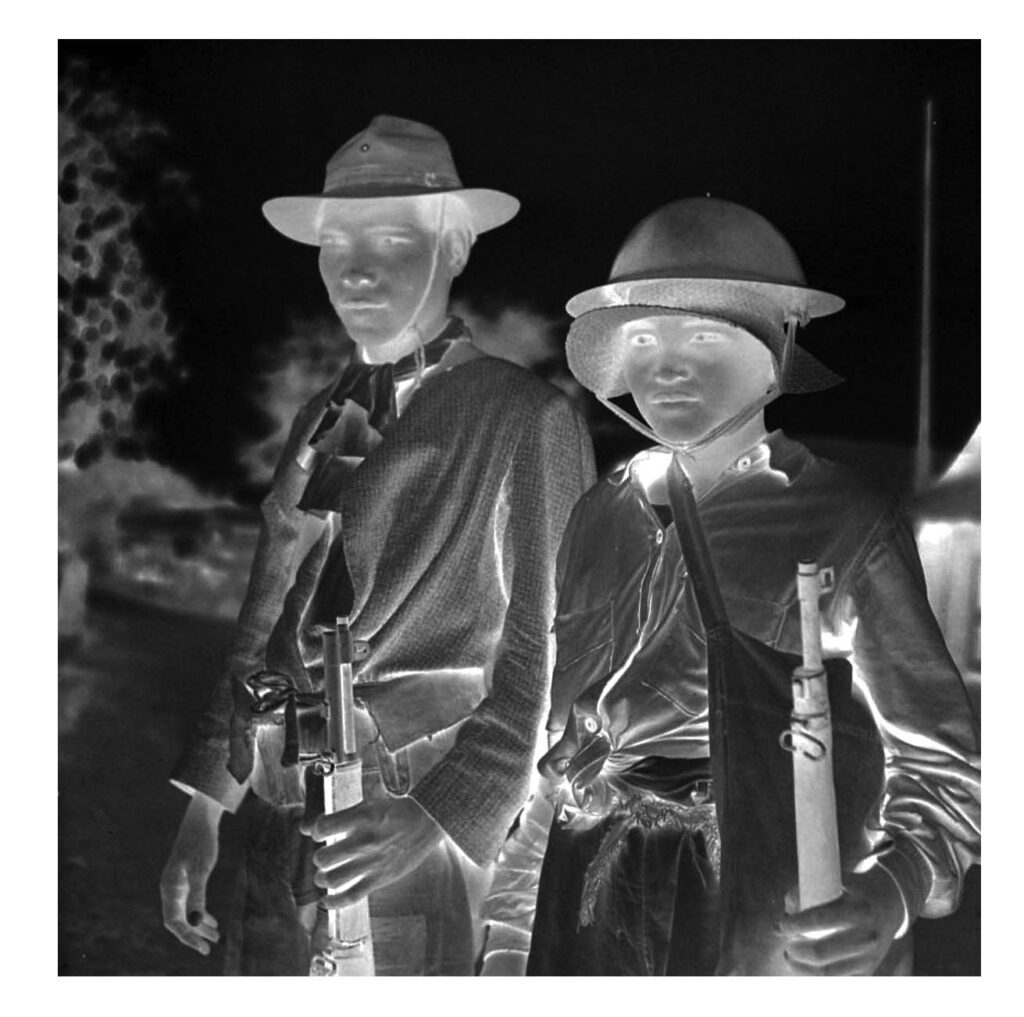

All I could hear was my deafening heartbeat until the whir of a jeep’s engine and its approaching headlights scared me into hiding in the tall grass. Four armed men in civilian clothes, their guns drawn and fitted with silencers, marched alongside the jeep. They surveyed the trail and the woods, thankfully oblivious to my hiding spot. I recognized them—the gossiping men at the bamboo house eatery who greeted my brother and me.

From the front of the jeep, a Filipino officer and an American in government uniforms exited and dragged my brother’s body into the woods.

“That’s another communist dead,” the American said.

“I don’t think this insurgency is good for our country,” the officer replied, flicking on his flashlight. “But they’re not communists. I fought alongside them against the Japanese during World War II. They’ve always fought for the independence of the mountain territories.”

“History will remember them as communists who tried to take over the Philippines. We’ll make sure of that to justify ending this rebellion.”

I crept after them, the cicadas singing and rustling leaves masking my footsteps. Every instinct screamed at me to flee, but I needed to know what these men were planning to do with my brother. I felt obliged to stay with him, even if he was dead.

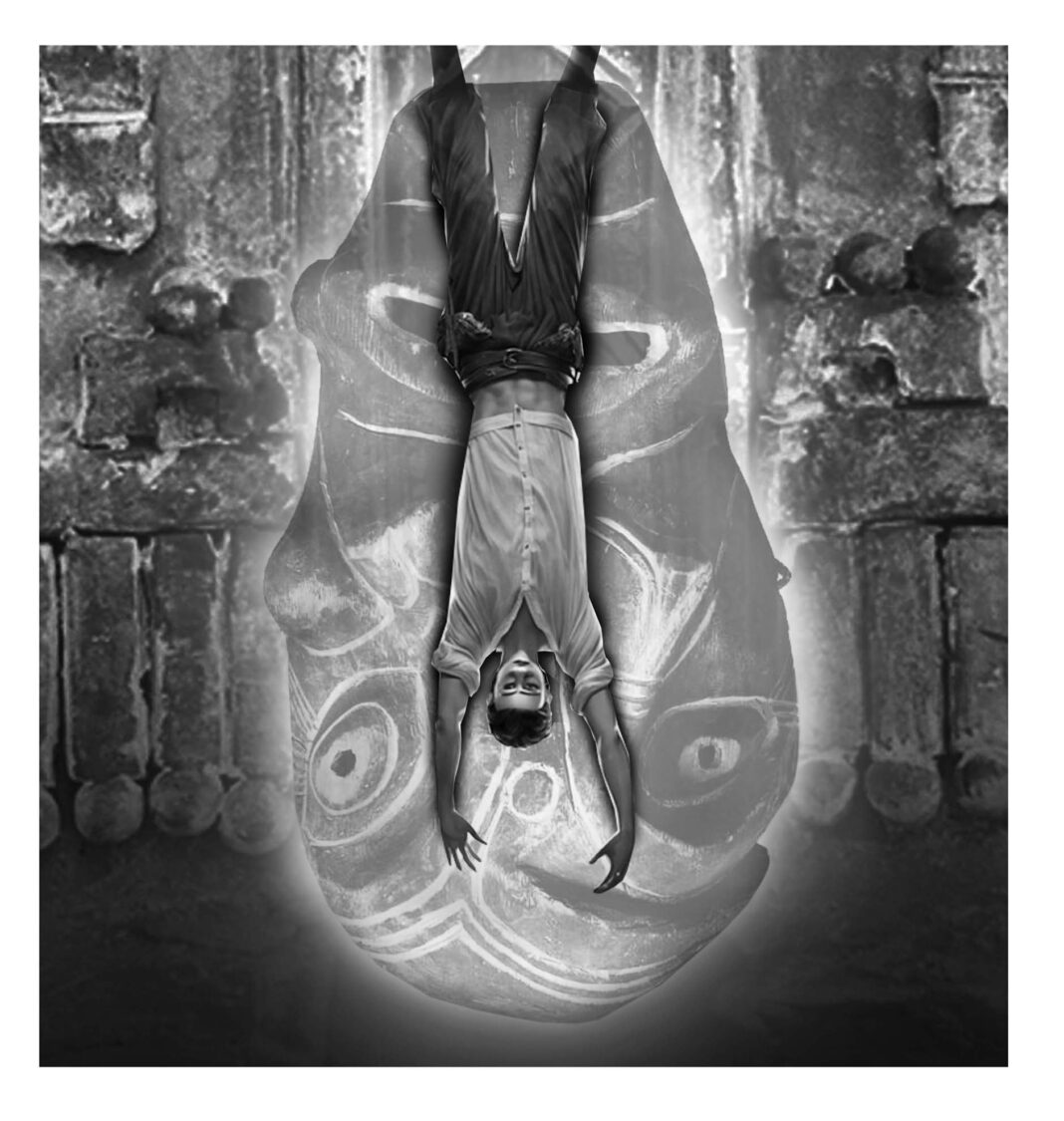

With a rope, the officer hung Ramil upside down from a tree by his heels. He held up a rod and struck it twice with his hammer, puncturing two holes in my brother’s neck. Blood slowly drained from his body, seeping into the ground. The officer and the American moved a few steps away, lighting cigarettes. How could they be so callous? I swallowed hard to keep myself from vomiting. Seeing my brother treated like butchered livestock and smelling the thick scent of blood in the air made me sick.

After a while, they took my brother down, mutilated him with blades to disguise the bullet wounds, and threw him back where they had shot him. The four men and the American got into the jeep. The officer shone his flashlight, sweeping the area until the beam briefly settled on me, then passed. “I thought I saw something in the brush,” he said.

“Well, did you see someone?” the American asked.

“No, sir.” The officer smiled at me before climbing into the jeep. “But if someone did see us and reveal what happened here, I’d dispose of him. I have eyes and ears on every villager.”

They drove off, the jeep’s headlights fading into the darkness. I sat on the forest floor, hugging my knees until morning, too afraid to retrieve my brother’s body. Surely, the officer had seen me. Why had he spared me? Perhaps because he knew I wasn’t a rebel and wanted to let me live. I wanted to tell the village what had happened, to seek justice for my brother, but the officer’s warning echoed in my mind—he would kill anyone who told the truth. So the truth had to stay with me.

The next morning, I knelt by my brother’s body. “I can’t seek justice for you. I can’t risk our friends and family in the village. Forgive me.”

Ramil stared at me, and I cried in shame. What they did to him…my brother didn’t even look human anymore.

I closed his eyes, hoping to grant him peace, and whispered, “I will never forget. The truth I shall bury in my heart until the time comes for everyone to learn what happened.”

When I returned to the village, I told everyone that I had been hunting with Ramil, lost sight of him, heard his scream, and then found him dead. Since I was known for being skeptical of superstitions, my story was believed. Other strange occurrences soon followed—the appearance of eye symbols near our homes, the destruction of property, and the disappearances of rebel sympathizers. My village withdrew its support, refusing to provide food and shelter to the Huks, weakening their influence in our region.

The national government’s psychological operations and the assassination of Huk members forced many to surrender, leading to the rebellion’s decline in 1951 and eventual end in 1954.