Guido hands the large envelope to Bea. She accepts it with two hands, but he doesn’t let go of it, suddenly hesitant. She looks too young and frail to be entrusted with important documents, or with anything that could seriously affect his life. Bea looks younger than her twenty-eight, maybe because she has smooth skin and short hair and stands five feet two only. At nearly six feet and with broad shoulders, Guido hulks over her.

Bea doesn’t pull the envelope, but neither does she take her hands off it. Her eyes seem to tell Guido that she’s waiting for him to make up his mind. The subtle steeliness reminds Guido that he could depend on her. She’s an exceptional woman, after all. She studied nursing at a university in a big city, graduating magna cum laude, and she worked abroad before coming back home a month ago to take care of her ailing mother. She’s more than intelligent enough to read the documents in the envelope and relay the contents to Guido in the local language and in simpler terms. He takes his hands off the envelope.

Bea checks the names and addresses printed outside the envelope, and then she tells Guido, “I have to read this first, Nong.”

Guido wants to say, “No. Open it right now and tell me what it says.” But based on his previous interactions with her, he knows that she has to read the documents carefully. Even if she’s intelligent and has interacted with native English speakers for more than two years, she still has to read two or three times some of the passages in the documents and has to look up online many of the terms. “How much time do you need, Ne?” he asks.

“Maybe thirty minutes, Nong,” she answers. “Or more. This seems to be thick.” Her dainty fingers crook awkwardly at the sides of the envelope. “I’ll just tell you when I’m done.”

Guido nods. “I’ll just be at the back.”

Bea takes the stairs to her room, and Guido goes to a small room at the rear part of the house, behind the kitchen. Guido turns on the electric fan and puts his backpack on the upper bunk of the bed. He then slips into the lower bunk, the steel frame creaking under his weight. Bea’s father, a retired colonel, allows Guido to use the extra room for househelps whenever he’s here in the plains. He’s been coming here two or three times a month, staying for up to a week sometimes.

It has been eight months and twenty days since Bobot, Guido’s third child and second son, was killed in Guido’s hometown in the mountains. It has taken that long for the regional office of the National Bureau of Investigation to conduct an investigation and file a complaint with the office of the provincial prosecutor and for the office of the provincial prosecutor to conduct its own investigation and issue a resolution. Guido doesn’t want to think how long the hearing would take and when the murderers would be put behind bars.

When someone knocks on the door, Guido opens it in a hurry, thinking it’s Bea. To his mild dismay, it’s retired colonel Tejero, his finely combed hair still wet from taking a shower. When Guido arrived earlier from the post office, the first person he looked for was the retired official, but Bea told him that her father was in the master’s bedroom, changing. “How was it, Guido?” says Tejero.

“Your daughter is still reading the documents, sir,” says Guido.

Tejero nods. “Don’t worry. Even if Bea’s not a lawyer, she can explain it to you as well as any lawyer can. You just need to give her a little time.” He then glances at his gold wristwatch. “I’m sorry, Guido. I can’t talk to you for long right now. I have to meet some old colleagues in the military.”

“It’s all right, sir,” says Guido. He goes out of the room and walks alongside Tejero.

“We’re planning to build a cockpit in your town. If it pushes through, I’ll get you as a caretaker.”

“Thank you, sir. Do you need a driver to your meeting, sir? I can take you there.”

“No, thank you. My driver is going with me. You just stay here and wait for my daughter to finish reading.”

They go out of the main door. Tejero’s pickup truck, bulked up and ultra polished, is waiting for him. The driver is wearing sunglasses and picking his teeth. “Don’t worry, Guido,” says Tejero. “Everything will go as it should. The NBI agent said so, didn’t he? The evidence is strong. The result of the autopsy is clear. A dead body cannot lie.”

“I’m hoping for the best, sir,” says Guido.

“The prosecutor will take your side, of course. It’s his duty to defend the complainant, to fight for the victim. The hearing will be set soon.”

“I hope so, sir. But I heard that the policemen might have bribed the prosecutor. They pooled their money, fifty thousand pesos from each of them. That’s three hundred fifty thousand pesos in all. Where would they use such a big sum? Their lawyer’s fee cannot amount to that at this point.”

Tejero glances at his wristwatch again. “Let’s just talk again when I come back, Guido. I have to be in the restaurant by four. Let’s decide what to do next when we already know the prosecutor’s decision.” He taps Guido on the arm and then gets into his pickup.

Guido feels dismissed. With resentment, he watches the vehicle leave, blowing smoke at him. Tejero doesn’t want to listen to him. The retired colonel doesn’t care. Indeed, why should he? He’s just helping Guido as a token payment for the services Guido has given him in the elections two years ago. Tejero ran for mayor in Guido’s hometown, three hours of travel away, even if the retired official just owns a farm there and lives most of the time in the plains. Guido was one of his campaign managers. Tejero didn’t win, but even so, Guido believes that his efforts brought in a good number of votes for the candidate.

Guido goes back to the small room at the rear of the house. He opens the window, takes out a cigarette, and smokes. His nerves ease up when he smokes. After finishing the stick, he is able to remind himself that he has no right to expect so much from the retired colonel. He’s been paid for his services in the elections. Tejero no longer has any obligation to him. He should even be thankful that Tejero welcomes him to his home. The retired colonel has done so much more compared to Guido’s own relatives, who have grieved and expressed indignation over what happened to Bobot but would not help or could not help Guido file a case against the suspects.

Guido opens his backpack and takes out the thick envelope that he always brings with him. The envelope contains affidavits, counter-affidavits, and other documents pertinent to his son’s case. He lays them on the ironing board that serves as a table in the room. He’s gone through the documents countless times, but he never tires of reading them, even if he doesn’t understand everything, and talking about them with other people, believing that each effort he exerts brings him closer to justice.

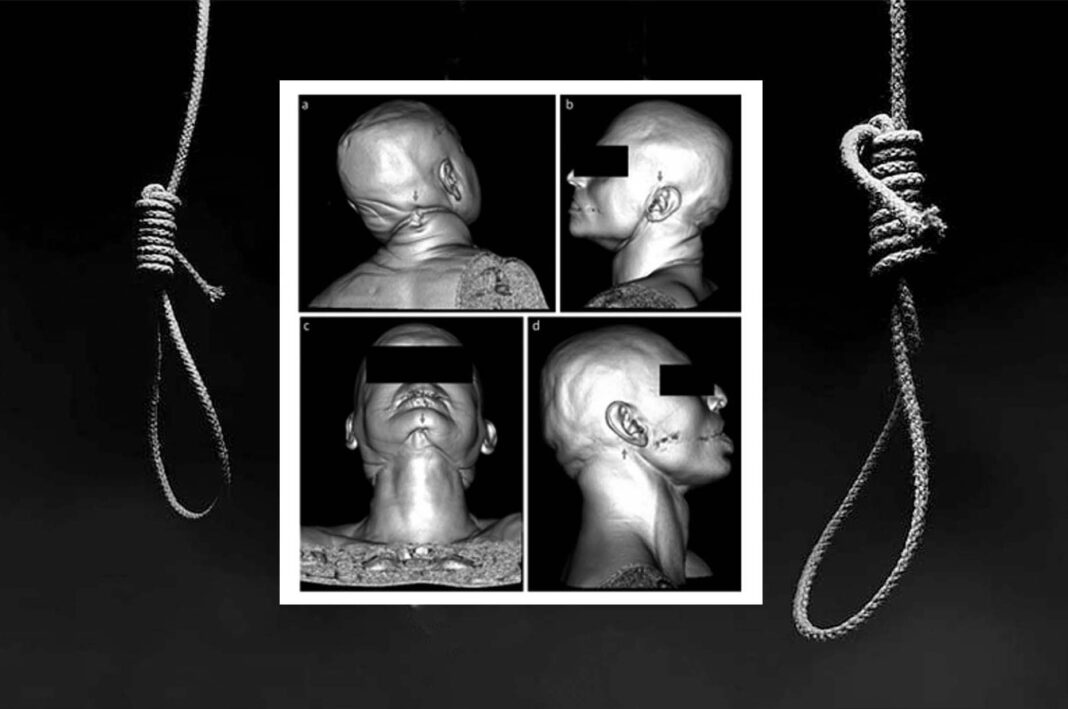

The most important of the documents is the autopsy report. Guido always places the two-page document at the top of the pile. Without the autopsy report, no case would have existed. Everyone would have to accept the report of the police officers that, while in a cell at the police station, Bobot banged his head on the bars and then hanged himself. The autopsy, requested by Guido and the retired colonel, revealed otherwise. The NBI medico-legal officer deduced that the police officers beat and hanged Bobot, and when they realized that they would be in serious trouble for what they had done, they replaced the rope with Bobot’s shirt. Under the autopsy report is the complaint that the NBI medico-legal officer filed against the six police officers who were on duty at the time of Bobot’s death, including the chief of police.

Next is the ruling of the Philippine National Police regional director on the administrative case against the police officers. Guido feels that his son has become a victim over and over. The PNP regional director has exonerated the officers from the charge of grave misconduct. When Bea read to Guido the verdict two weeks ago, she said that the PNP provincial office, after conducting a hearing, filed a weak case against the officers; hence, the regional director dismissed the case with ease.

Guido wants to hurl the documents on the wall. Most of them have made the simple truth complicated. They have protected the criminals instead of making them pay. So far, the results for Guido have been either negative or delayed. What kind of justice is that? True justice means all the killers of his son have been dismissed from service and put behind bars by now or, better yet, handed to him for torture and hanging, as what they’ve done to his son.

To take the murderous thoughts out of his mind, Guido smokes again. He’s on his fourth or fifth stick when a househelp knocks on the door. She tells Guido that Bea is looking for him. Guido puts the documents back inside the envelope and goes out. He sees Bea at the dining table, the documents from the prosecutor’s office laid in front of her, out of the envelope. As soon as he’s seated opposite her, he asks, “What’s the decision, Ne?”

“Where do you want to start, Nong?” says Bea. “Much of these are attachments, such as reports and affidavits. You’re familiar with all of them. The actual resolution, the main document, is six pages long.”

“Just tell me the decision straight away.”

“All right, Nong. It’s here on the last page. We’ll just go over the other pages if you have questions later.”

He knows that if the decision had been in his favor, she would have congratulated him by now. There would have been no need for her to be careful about what to say. He’s no longer surprised when she tells him, “The complaint was dismissed.” But he has not been prepared for the emotion that wash over him. In a shaking voice, he asks, “Why?”

“It says here ‘no probable cause.’ The prosecutor finds the evidence not strong enough to charge the policemen with murder.”

“What more does he want? Weren’t the marks in my son’s body evidence enough? Does he want my son to rise from the dead and narrate everything himself?”

Guido realizes that his voice has been so loud, he sounded as though he was scolding Bea. He shouldn’t burst out in front of her. She’s not the enemy. She’s on his side. To spare her from his anger, he stands up and leaves the table. He hears her say, “The decision may be overturned, Nong,” but he continues walking away.

In the small room at the back of the house, Guido smokes again. He doesn’t feel calmer until about half an hour later. When he goes out, Bea is still at the dining table but helping her mother eat. Mrs. Tejero has gone nearly blind from diabetes. Although she can use the spoon and fork on her own, someone has to be around to make sure she doesn’t spill anything. Bea looks at Guido. He gives her a polite nod and goes out the front door to kill time. The lawn has become weedy, the plants yellowish. Mrs. Tejero used to tend to them every day when she was better, and Guido had even helped her once transfer some pots from one spot to another.

After twenty minutes or so, estimating that Mrs. Tejero must be done eating, Guido goes back inside the house. The dining table has been cleared of things except for the documents from the prosecutor’s office, and Bea is alone. He takes the seat opposite her. “I’m sorry for my behavior earlier,” says Guido.

“It’s all right, Nong,” she says. “I understand. Let’s focus on what you can do next.”

Bea explains Guido’s options. He may file a motion for reconsideration with the office of the provincial prosecutor, and if the motion is denied, he may appeal to the regional prosecutor. If the regional prosecutor still rules against Guido, he may file a petition for review with the Department of Justice. At any time, Guido may also file a complaint with the regional office of the Commission on Human Rights. The commission may conduct their own investigation, but just like the NBI, they cannot render judgment on the suspects. They can only help the complainant file criminal and administrative cases, and since the proceedings are already ongoing in the case of Bobot’s death, the CHR can only monitor the proceedings.

“So far, Nong, the decisions have not been in your favor,” Bea says. “Maybe the administrative case was whitewashed. It’s not surprising if PNP officials wanted to protect their colleagues. Maybe the provincial prosecutor was indeed bribed. I know Alvin Petilla. He was my schoolmate in high school, and he didn’t strike me as a particularly principled person. But before we accuse those government employees of corruption, let’s look at the complaint first. It’s the main problem, in my opinion. It’s weak.”

“How?”

“The NBI medico-legal officer could have worded the complaint better and made it longer than the two pages that it is. He failed to emphasize many important points. For example, the autopsy report states that the ligature mark on your son’s neck measures zero point five to one point four centimeters. That’s obviously the size of a rope. A T-shirt would have made a wider mark. The officer did not mention the measurements in the complaint. Also, he did not explain sufficiently the hematoma in your son’s head. It seems that it was caused by blows on the back of your son’s head. The injury could not have been self-inflicted. Or if it had been self-inflicted, your son would not have been able to do more after that. He would have been too disoriented to step on the toilet bowl, tie his shirt on the bars of the ventilation window, and hang himself.”

Guido feels lost. Of all the people who have been helping him, he considers the NBI agent as his most trustworthy ally, his biggest source of confidence, and now Bea is telling him that the agent is negligent or incompetent.

“My father contacted the NBI for you, Nong,” Bea continues. “I’m sure Dr. Velez, the medico-legal officer, is on your side. But NBI agents are busy. They investigate a lot of cases. The agent must have done his best for your son’s case, but the output is not the best for the case. You should have hired your own lawyer, Nong. A lawyer could have presented the case more convincingly. A lawyer would know what the prosecutor or the judge is looking for.”

“I can’t afford to hire a lawyer, Ne. I leased half of my farm and sold one of my carabaos, and I use the payment in coming here in the plains. Other than that, I have no other resources.” Guido also explains that Bea’s father has asked his friend Atty. Macariñas to help Guido, but the lawyer lives in the next province, and for his clients there alone, he barely has enough time, so all he has done for Guido was give advice once and notarized for free the documents for Bobot’s case.

“Why didn’t you ask for help from the Public Attorney’s Office?” asks Bea.

“I heard that some of the policemen in my town have relatives there,” says Guido. “I can’t trust people here in our province, Ne. My son’s killers have connections in almost all government offices.”

“All right, Nong. I’ll help you find a private lawyer. It’s on me.”

Guido is not able to react right away.

“I mean, I’ll help until the trial is underway,” explains Bea. “You don’t have time to look for money. Motions and appeals have a time limit. You forfeit the right to do them after a certain number of days. So for the meantime, I’ll take care of your lawyer’s fees.”

“Are you sure, Ne?” says Guido. “Your family spends a lot on your mother’s medication.” The retired colonel has told Guido before that Mrs. Tejero has to be injected with insulin every day and undergoes dialysis twice a week.

“My father takes care of my mother’s medical expenses,” says Bea. “I have my own savings. Don’t worry about it.”

“I’m embarrassed to accept anything from you, Ne, but there’s nothing I can do but be grateful.”

“Don’t mention it, Nong. I’ll also look for doctors who can corroborate the findings of the NBI medico-legal officer. We may also need a psychiatrist or psychologist who can attest that, with your son’s state of mind at the time, it was not likely for him to commit suicide.”

Bea’s image blurs in Guido’s eyes as his tears flow. He can’t remember the last time he felt something positive. His hope is high again. “I’m greatly indebted to your father and you,” he says, wiping his tears with his hand. “Thank you, Ne. At last, my son’s killers can be brought to justice.”

Bea’s expression doesn’t change. “It’s still a long fight, Nong, and there’s another thing that the lawyer has to emphasize.”

“What is it?”

“The motive of the suspects.”

“The motive? The policemen were abusive.”

“It’s not enough, Nong. It didn’t convince the prosecutor. He says so in the resolution. He’s incredulous that the policemen killed your son on a whim. In our laws, there’s something called ‘presumption of regularity.’ Unless there’s strong evidence to the contrary, police officers and other government employees are presumed to be doing their job properly. Whether he was bribed or not, the prosecutor can reasonably say that there’s no reason for the policemen to kill your son.”

“What should the lawyer do?”

“It’s actually you who has to do something, Nong.”

“What is it?”

“You have to tell the truth. You have to tell everything.”

“What do you mean?”

With a bit of hesitation in her voice, Bea says, “My father told me before that your son had been taken to the police station many times. I’m not sure if the figure was correct, but it seemed too high.”

Guido nods. “That’s true,” he says in a weak voice. “He’s been arrested about twenty times.” Guido’s family live close to the public market, and Bobot often got involved in verbal and even physical tussles there, especially when he’d had a drink too many. Sometimes he would destroy property. On the day he was killed, Bobot had gotten into an argument with a bakery owner about the previous election. The bakery owner mocked Bobot because Guido’s whole family supported Tejero, a candidate who had a poor chance of winning. Bobot threw a rock at the bakery, shattering the glass of a display case. Police officers took the complainant and Bobot to the station to settle the matter, but the fight only became worse. Bobot choked the bakery owner, so he was dragged into a cell. Bobot continued to be unruly, and later that evening, Guido’s family was informed that Bobot had hanged himself.

“The policemen were fed up with your son,” says Bea. “There was no end in sight to the nuisance he created, so they decided to put the matter into their hands once and for all.”

“No,” says Guido, shaking his head. “My son had changed. Since he met this girl from another barangay, he had refrained from drinking. He already had plans, in fact, to settle down with the girl.”

“It doesn’t matter, Nong,” says Bea. “You can’t portray your son as a gentle person, an innocent victim. That would only strengthen the argument of the policemen that they had no reason at all to hurt him. If anything, you should emphasize how much of a menace your son had been. Ask for a copy of the blotter, particularly the entries that involved your son. Use the police station’s own document against the officers. The extracts will show how your son got into their nerves so many times in the past, gradually and consistently causing them to harbor ill will against him, making them so exasperated that they eventually blew up and killed him.”

Guido stares at Bea in disbelief. He has always thought of her as a nice and pampered daughter. Only now does he realize that she’s as cunning and bold as her father. “I can’t do that, Ne,” says Guido. “My son is gone now. The least I can do for him is to protect his name.”

“It’s not good for your son’s name, Nong, but it’s good for the case.”

He shakes his head again. “I can’t do it. I can’t . . .”

Bea puts the pieces of paper inside the envelope and hands it to Guido. “Think about it, Nong,” she says. “Yours is the decision that matters most.”

Guido feels that he has nodded, but he’s not sure. His body feels detached from his mind. He takes the envelope from Bea, and unsure of what words or gestures he has given her, he goes to the small room at the rear of the house. He puts the envelope on top of the older envelope, on the ironing board.

His mind becomes clearer after smoking two sticks of cigarette. He ponders on what Bea has suggested. Some of the entries in the police blotter contain not only his son’s name but also his. For four or five times, Guido himself has asked the policemen to detain Bobot because he was going berserk in their home, drunk and sometimes high on drugs, threatening to kill his siblings and parents, even succeeding once in stabbing his older brother. Guido doesn’t want to relive all that. He doesn’t want to confront what his conscience is telling him—that what happened to Bobot is the ultimate proof of his failure as a father. He has not raised him well. He has not done anything as his son slid deeper into destruction. He has watched helpless as Bobot brought hell to himself, to their family, and to the community. Guido doesn’t want to accept what his neighbors are whispering to one another—that the policemen have done the town a favor by killing Bobot. Mosquitoes buzz around Guido’s legs. He looks out the window and sees that the sun has set. He closes the window and the curtains and lights another cigarette, drowning himself in the smoke.