By Harvey Sapigao

In the Philippines, breast cancer is the most common type of cancer among women, with over 33,000 new cases reported in 2022. That year, it claimed more than 11,000 lives, making it the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the country, following lung cancer.

Aggressive breast cancers can spread to other organs, a process called metastasis. Before it does, however, the cancer cells must first invade the lymphatic and blood vessels, which enables them to travel to different parts of the body. This condition, known as lymphovascular invasion (LVI), serves as an early indicator of metastasis for doctors. Currently, LVI can only be detected by examining tissue surrounding the tumor that has been surgically removed.

Now, biologists from the University of the Philippines (UP) have developed a mathematical model that can detect LVI in breast cancer patients even before surgical treatment. Their study also revealed links between LVI and drug resistance, helping explain why breast cancer patients with LVI respond poorly to anticancer drugs.

“If we can detect LVI earlier, doctors could personalize patient treatment and improve their outcomes. This could help avoid ineffective treatments and focus on strategies that work better for aggressive breast cancer,” said corresponding author Dr. Michael Velarde of the UP Diliman College of Science Institute of Biology (UPD-CS IB).

Along with Dr. Velarde, the study’s authors are Allen Joy Corachea, Regina Joyce Ferrer, Lance Patrick Ty, and Madeleine Morta of UPD-CS IB, and researchers from the Philippine Genome Center and UP Manila.

Before surgery, breast cancer patients are given anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin and anthracyclines to shrink the tumors first. In some cases, the treatment is so effective that the tumors disappear completely, eliminating the need for surgery. In other cases, however, the tumors only shrink, requiring surgical removal. It is only after this procedure that doctors can determine if the patients have LVI.

From the clinical data of 625 breast cancer patients at the Philippine General Hospital, along with publicly available data, Dr. Velarde and his co-authors observed that the majority of patients with LVI also responded poorly to the anticancer drugs.

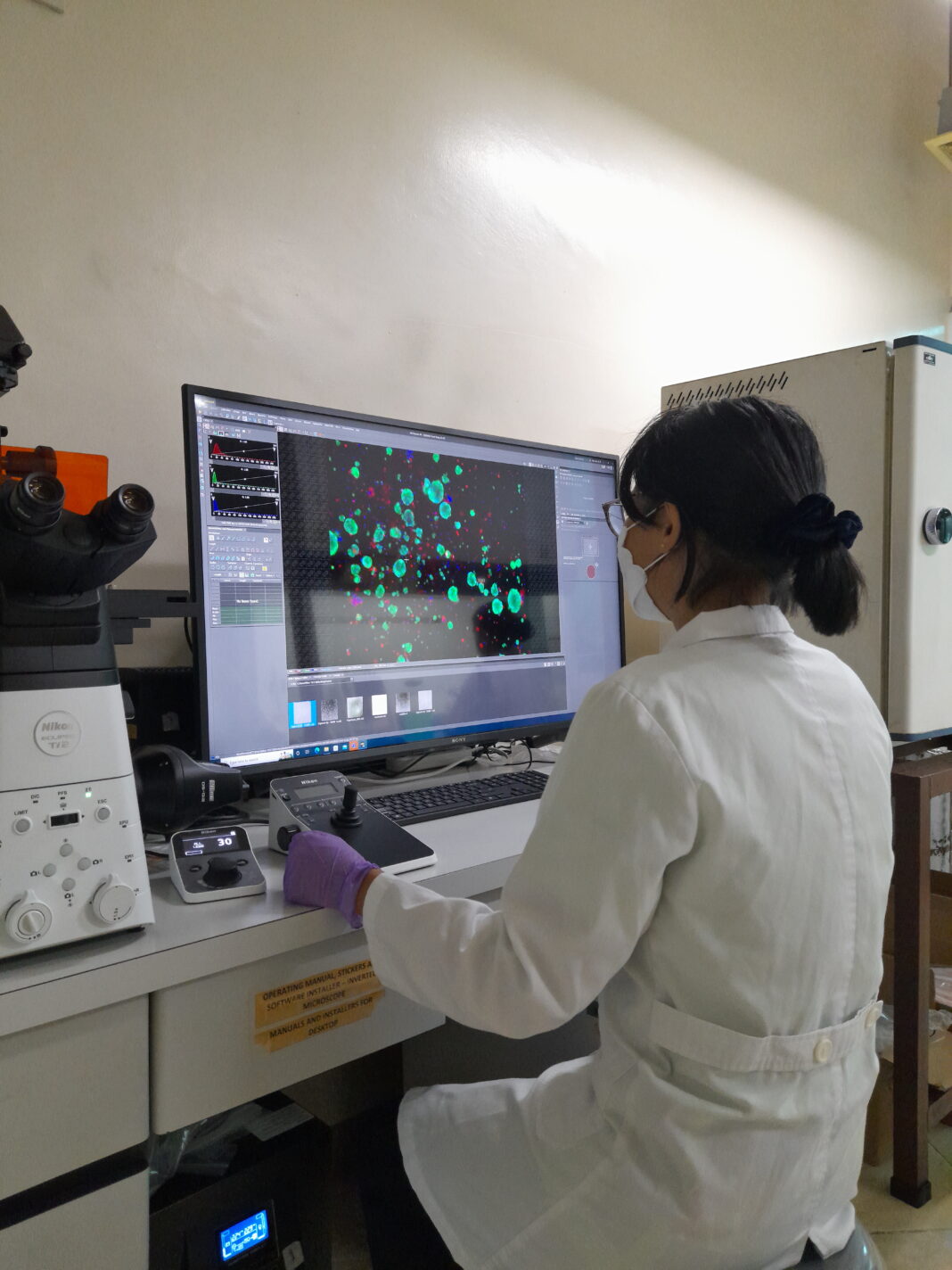

They further confirmed the link between LVI and drug resistance by collecting tumor samples and growing them in a lab into organoids – small, organ-like structures that mimic real organs. Their tests revealed that LVI-positive organoids were indeed less receptive to anticancer drugs compared to LVI-negative ones.

They discovered that certain genes involved in breaking down anticancer drugs, called the UGT1 and CYP genes, are more abundant in patients with LVI. When these genes are more abundant, the drugs are broken down more quickly, reducing their effectiveness. As a result, patients with high activity of UGT1 and CYP genes are more likely to have tumors that survive chemotherapy and eventually metastasize.

Using these insights, they developed a regression model that analyzed the expression patterns of UGT1 and CYP genes. Their model correctly predicted LVI status at the time of biopsy and before surgery 92% of the time.

“Importantly, our approach can be implemented in the Philippines using locally available genomic technologies, making earlier detection and tailored treatment more accessible to Filipino patients,” added Dr. Velarde.

However promising, Dr. Velarde noted that the model is still in its early stages of development and is not yet ready to replace current methods for diagnosing LVI. “More validation studies are needed before this can be used in clinics.”

The authors also plan to validate their results by testing the gene signatures of larger groups of Filipino breast cancer patients. They plan to further investigate how UGT1 and CYP genes are related to LVI to identify drug combinations that work better for LVI-positive patients. “Our goal is to develop a practical test that can be used in Philippine hospitals to guide doctors in choosing the best treatment for each patient,” concluded Dr. Velarde.

For interview requests and other concerns, please contact media@science.upd.edu.ph.

References:

Corachea, A. J. M., Ferrer, R. J. E., Ty, L. P. B., Aquino, L. A., Morta, M. T., Macalindong, S. S., Uy, G. L. B., Odoño, E. G., Llames, J. S., Tablizo, F. A., Paz, E. M. C. C., Dofitas, R. B., & Velarde, M. C. (2025). Lymphovascular invasion is associated with doxorubicin resistance in breast cancer. Laboratory Investigation, 104115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labinv.2025.104115