Three huge cross figures made of fine wood were slowly being painted black by a crowd of men. They sat on makeshift bamboo benches in front of a small sari-sari store, holding a paintbrush in one hand and a bottle of beer in the other. Some had gathered by the concrete wall, crafting their own versions of the crown of thorns and wooden paddle. The children observed them intently, silently planning their own pamagdarame.

A group of old women sat in front of the chapel across the store, where the setup for the pabasa was located. A huge arch was stationed at the top, and the pasyon had been laid on the table, a white cloth spread beneath it in its glorified purity and cleanliness.

A man in his late forties called out to the young boy standing frozen on the side of the street. “Kiel! Greet Father Mike for me, okay? Tell him I’ll be there later to fix the ceiling!”

Ezekiel barely heard him at first, his gaze lingering on the men working under the midday sun, their backs slick with sweat, muscles shifting as they hoisted wooden beams. He quickly looked away, swallowing the thought.

“I will, Kuya Jo. But please, stop drinking, or I’ll tell Ate Tess!” he teased.

Jo was tying back his long, wavy hair. “I can’t quit drinking. If I do, I’ll start feeling the cuts on my back.”

Ezekiel grabbed his bicycle from the roadside. “You don’t have to do that anymore. Aren’t you getting a little old for it?”

“Just too many sins I need to repent for this year,” Jo replied jokingly.

Ezekiel shook his head in disapproval. “Tsk, I need to go. Please tell nanay I’ll be staying late at the church.” He grabbed his bike and pedaled away.

The church was filled with townsfolk listening intently to the sermon. Named after their patron saint, San Nicolas, it wasn’t as grand as some parish churches, but its modest size was enough to welcome the entire community. The church had stood there long before Ezekiel was born, its walls familiar to everyone in town. As Ezekiel entered, he was warmly greeted by those who had known him since childhood.

It was just another ordinary day for him. He knew the church would be crowded, after all, it was Maundy Thursday. People had come to complete their Visita Iglesia, some seeking repentance, others hoping for blessings, and a few simply testing their luck, praying to be rich. The morning had been hectic, and as the sun climbed higher, Father Mike finally told everyone to take a break and return later that evening.

Ezekiel decided to ride his bike along the roadside of their barrio. He passed the same acacia trees he had seen since childhood. Seventeen years in this place felt like a lifetime.

But if nothing else, being stuck here had given him the ability to memorize every inch of the town. He knew which trees had names carved into them and that a bird’s nest had been perched atop the stained glass of the third Station of the Cross for as long as he could remember. He hated this place. He wanted to escape, weary of the constant gaze of people expecting great things from him.

Everyone knew him as the good kid, the role model, the one who never talked back, never broke the rules, and always did what was expected of him. He was the type of person who would lend a hand even when it meant sacrificing his own comfort. Adults praised him, using him as an example for their own children, while his peers either admired him or resented him. But what they didn’t see was the pressure—the way their eyes were always on him, watching, waiting for the moment he would slip. One wrong move, and everything they built him up to be would come crashing down.

On his way downhill, he stopped by the talipapa, a makeshift market built from thin plywood and sun-bleached tarpaulin, to buy an apple. As soon as he stepped in, Aling Tessie, the vendor, immediately noticed him. She gave him a warm but knowing smile, her hands never pausing as she weighed a bundle of tomatoes for another customer.

“Uy, Ezekiel!” she called out, loud enough for everyone nearby to hear.

Ezekiel felt shy and responded, “Po?”

“Still as polite as ever, ha. No wonder the church folks love you.”

There was something in her tone, something that lingered in the air between them. A few other vendors turned their heads. One of them, an old woman selling dried fish, leaned closer to her seatmate, whispering just loud enough for Ezekiel to catch fragments of the conversation.

They weren’t just talking about him—they were talking about his mother. About how he didn’t have a father. About how they knew who his real father was.

Ezekiel felt the familiar weight of their words pressing against his skin. He forced a smile as Aling Tessie handed him the apple.

“Salamat po,” he said, slipping a few coins into her palm before quickly tucking the fruit into his pocket.

As he walked back to his bike, the murmurs followed him. They always did.

He gripped his handlebars and exhaled sharply. He might have been the good kid, but he carried a sin that was never his to bear. He couldn’t wait to leave this place behind.

He went back to the church after getting bored. The devotees had dispersed throughout the town. He heard loud voices on the left side of the church where the priest’s office was located. Even the thick wall of the office couldn’t smother the loud noises inside. At the back of his head, he knew who was inside with the priest. He approached the door to see what was happening.

“You know he’s going to college soon! Where’s the money you promised?” A woman in her late thirties, dressed in a tight tube top and ripped shorts, pointed at Father Mike, her voice edged with hysteria.

“I know. I’m sorry. It might be best to enroll him in the college nearby. It’s cheaper there,” Father Mike replied.

She waved a hand at the bottles of alcohol scattered across the room. “And what’s all this crap? Are you drinking again?”

Gripping the doorknob, she scoffed, voice dripping with sarcasm. “Go ahead, kill yourself.”

Ezekiel froze as he watched her storm out.

Outside, she barely looked at him before snapping, “Great, you’re here! Tell your father we need money. I can’t send you to college by myself.” She pulled a box of cigarettes from the pocket of her shorts, pressing a stick between her red lips before lighting it.

Ezekiel took her hand and tapped it to his forehead.

“Go home when you’re done here.”

“I will, Nay,” he murmured, bowing his head as if ashamed to be there.

She exhaled a cloud of smoke, voice dropping into an audible whisper. “Your God won’t feed you or send you to a good college…neither will that man who calls himself a priest.”

The door remained open when his mother left. Father Mike saw the boy and signaled him to enter.

“I’m sorry, anak. Please don’t listen to your mother. I’ll try to see what I can do. Do you have a course in mind?” Father Mike’s voice turned hoarse, his eyes lingering on Ezekiel as though he regretted letting him in.

“I haven’t chosen yet. I’ll take whatever makes the most money…” Ezekiel kept his gaze on his shoes. “Or whatever my mother wants for me.”

He couldn’t bring himself to look at the priest, knowing the truth they never spoke of. He had always found something unsettling in the eyes of the people he talked to—a black void where their secrets festered. He had learned to avoid them.

Father Mike let out a slow breath and rubbed his temples, as if trying to push back a headache. He looked at the boy in front of him, the weight of unspoken words settling between them.

“Choose whatever you want, Ezekiel. It doesn’t matter what she wants—”

“I want to leave this town!” Ezekiel cut him off.

He clenched his fists. “Don’t act like you care about me!” he shouted, finally meeting the priest’s eyes.

He stood up and left the office. He didn’t know where he got the confidence to shout, but he knew that all his anger had been boiling up. He’s mad at everything—the people who had been gossiping about him, his peers who seem comfortable being stuck in this place, the sin of being born from a priest—he’s mad at the world for being born with sins he never had control of.

He went back inside the church where he could be alone. 3:00 p.m. flashed on his watch. The holy hour, he thought, only that he still does not understand why it was called that way. The temperature was the usual, it was hot and humid outside. The whirring sound of the electric fan echoes inside the church and in the confessional where he is. He was sitting on the wooden plank, trying to fit himself inside the small space of the box as if hiding from someone.

In his hand was a jar of unconsecrated ositya that he was eating little by little while letting them melt on his tongue. He tasted something peculiar with the ostiya as it left a sweeter aftertaste that day. In his position, the sunlight passes through the crisscross pattern inside the confessional, creating shadows and hitting his face. He flicked his hands on his sutana, which has crumbs of wafers all over it now. He was thinking loudly about it, he used to be scared of this box. He was not claustrophobic at all, it was just that he was wary of being inside of it.

Ezekiel took out his little notebook and a pencil from his pocket. He stared at the page where his list was written and put checkmarks on “eat ostiya” and “confessional.” There were still at least two unchecked circles on his list. At the very bottom, written in careful letters, was “Leave this place.” Inside the parentheses, a small star was drawn next to it.

Ezekiel flipped through his notebook, his fingers restless as they searched. Midway through, he stopped. A torn page from a brochure peeked out from between the sheets. His hands trembled as he pulled it out, lifting it to his eyes, tracing the image as if trying to memorize every detail.

The summer heat was nothing compared to the fire running through his veins, a tingling, pulsating warmth that burned from the inside out. He sighed heavily, closing his eyes for a moment before carefully folding the section he had saved. His gaze lingered on the image, broad shoulders, the sharp lines of muscle catching the light, a sheen that made the figure almost lifelike.

He put his notebook down beside him. He got up, removed the sutana, and folded it neatly. Closing his eyes, he let his fingers run across his chest before settling on the golden cross pendant hanging from his necklace. He held it in his palm and knelt on the padded wooden plank on one side of the confessional.

“God strengthens…” he whispered under his breath. For a moment, he felt calm and collected. But inside, he was lonely and afraid at the same time.

Ezekiel stood up, collected his things, and before leaving, he took the plastic bottle filled with stolen wine from the priest’s office and drank.

When he returned home, three black crosses lay undisturbed on the concrete. The men kept drinking, the children were called in for their siesta, and the relentless hum of the pabasa vibrated through the humid air, crackling from worn-out speakers that strained to carry the voices singing since dawn.

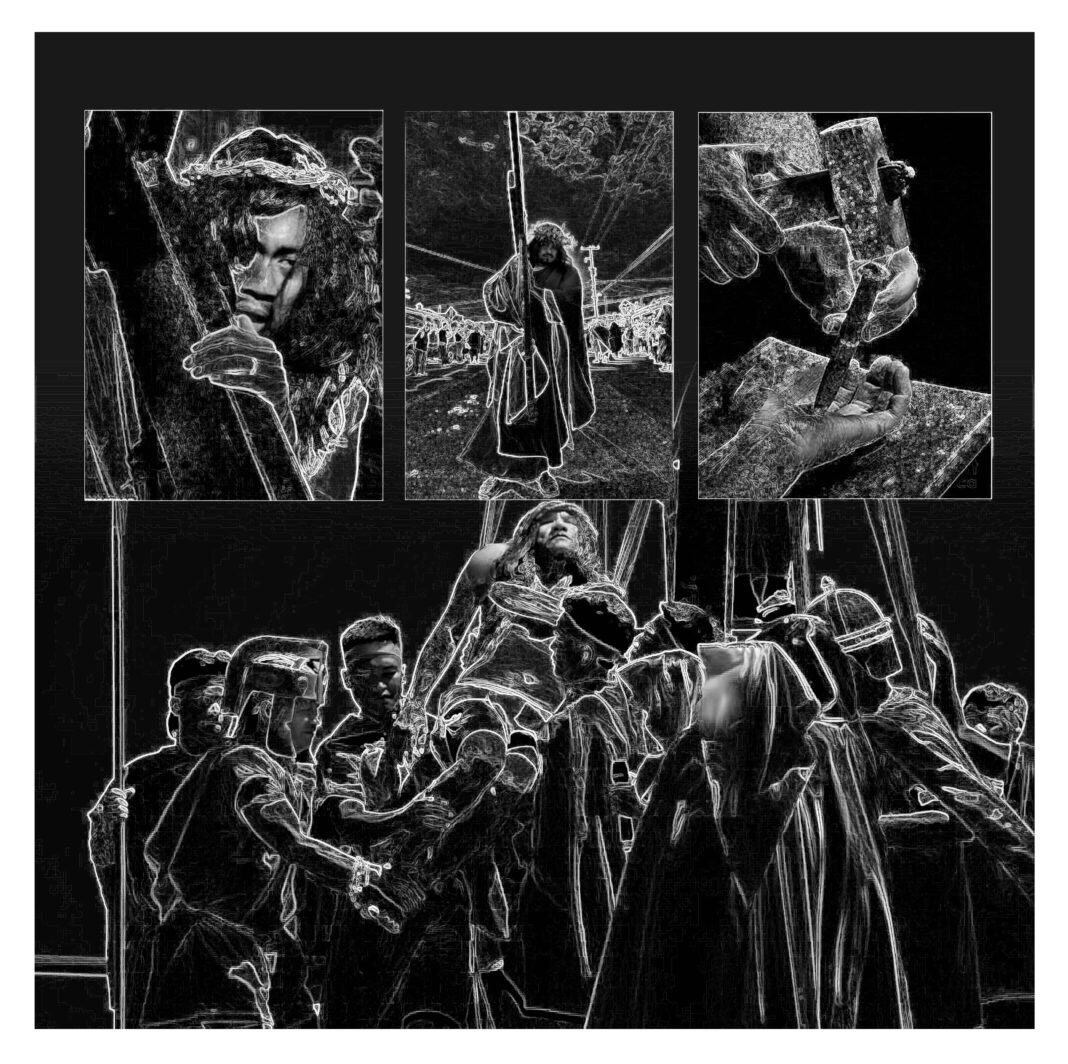

The town felt like it was holding its breath. Tomorrow, everything would change. By morning, tourists would flood the streets, their cameras flashing, eager to witness a crucifixion in the flesh. The Via Crucis was the heartbeat of their town—the one day when its quiet streets pulsed with life. Not Christmas. Not New Year. This was their grandest spectacle, a performance of suffering and devotion laid bare for the world to see.

Ezekiel should have felt the same excitement, the same reverence that everyone else did. But as he stared at the crosses waiting on the ground, his stomach twisted.

He saw the organizers approach the men. Jo greeted them with a knowing smile as if he had been expecting them already.

“Our guy backed out last minute, and the event is tomorrow. He got scared, e. We can’t cancel it when there are a lot of tourists now. Can you do it for one more year, Jo?”

“Of course, sir. I’ll talk to my wife about it, but maybe I could get a little more from the donations this year?” Ezekiel overheard his neighbor, Jo, who had been carrying the cross for three decades now, agreeing to play the role of Jesus once again.

Ezekiel slipped away, weaving through the narrow passageways of barong-barong. The rancid air no longer made him flinch, nor did the muffled arguments of newlyweds just beyond the thin plywood walls. Here, privacy was a luxury, and secrets never stayed hidden for long.

Ezekiel turned to see Ate Tess, Jo’s wife, standing with her hands on her waist, fuming and slick with sweat. The swell of her pregnant belly was visible beneath her dress. “Kiel, where’s Jo?”

“I saw him at the kanto, Ate Tess. He’s talking to the organizers.”

She exhaled sharply, making the sign of the cross. “What do they want now? Susmaryosep! Let him retire already.”

“Ate Tess, let him be. He’s asking for more compensation. Don’t worry.” Ezekiel tilted his head toward her belly, lips pursed. “That’s due next month?”

Ate Tess let out a sharp breath, wiping the sweat from her forehead with the back of her hand. “Ah! Yes. Soon, we’ll have enough to make a whole basketball team.” She smirked, shifting her weight to one side. “Aydana. Damn that good-for-nothing man.”

She adjusted the loose fabric clinging to her skin, her irritation heavy in the sweltering heat. “I’ll go to him. If I can’t talk some sense into that stubborn head, please watch over him tomorrow, okay?”

“Yes, Ate Tess,” Ezekiel nodded. “I’ll make sure he gets through it.”

Ezekiel didn’t return to the church that night. Kuya Jo had told him to pack their things for tomorrow and carry the bag. He knew the drill. Bottled water, an extra shirt, towels, alcohol, and hydrogen peroxide, he gathered everything without needing to be told. This was not his first time assisting the man, and he already knew the routine by heart.

Ezekiel woke to the heaviness of morning heat, the tang of soy and vinegar from the adobo hanging in the air. The door swung open, hitting the wall with a dull thud. His mother wobbled inside, a cigarette dangling between her fingers. The sheer white of her shirt clung to her skin, barely hiding the black bra underneath. Strands of hair stuck to her sweaty forehead, tangled around the silver hoops in her ears.

“Ezekiel! Where are you going, anak?” she slurred, her voice too loud for the small room.

He pushed his plate aside. “Ma, you’re drunk again.”

She scoffed, swaying as she took a drag from her cigarette. “Why are you mad, huh? You think you’re better than this? Stay home and work instead!”

Ezekiel felt the sting in his chest, but he said nothing. Instead, he took her by the arm, guiding her toward the woven banig spread across the floor. She muttered something incoherent before settling down, her breath slowing, the cigarette slipping from her fingers. Within minutes, she was snoring.

He ground the cigarette on the floor, the ember snuffing out with a faint hiss. Slinging his bag over his shoulder, he stepped outside without a word.

The morning air was thick with the scent of brewing coffee as he made his way to the neighbors. Ate Tess sat on a low stool, cradling a mug in one hand, the other absently rubbing her swollen belly. Kuya Jo leaned against the doorframe, steam curling from his cup. Inside, their nine children lay tangled on the floor, limbs overlapping, their steady breaths rising and falling in unison, packed so tightly they looked like sardines in a can.

“Oh! You’re a bit early,” Kuya Jo said, setting his cup down with a soft clink. He stretched his arms, rolling his shoulders as if shaking off the heaviness of the morning. “Go to the court first. I’ll meet you there.”

At the basketball court, Ezekiel watched as men lounged on the benches, some fanning themselves with old newspapers, others absently tapping their feet against the concrete. The air buzzed with idle chatter, anticipation simmering beneath their voices. Organizers weaved through the crowd, barking instructions, hauling props, and adjusting wires. Nearby, carpenters crouched over planks of wood, hammering and sawing, the skeleton of a makeshift stage slowly taking form under their calloused hands.

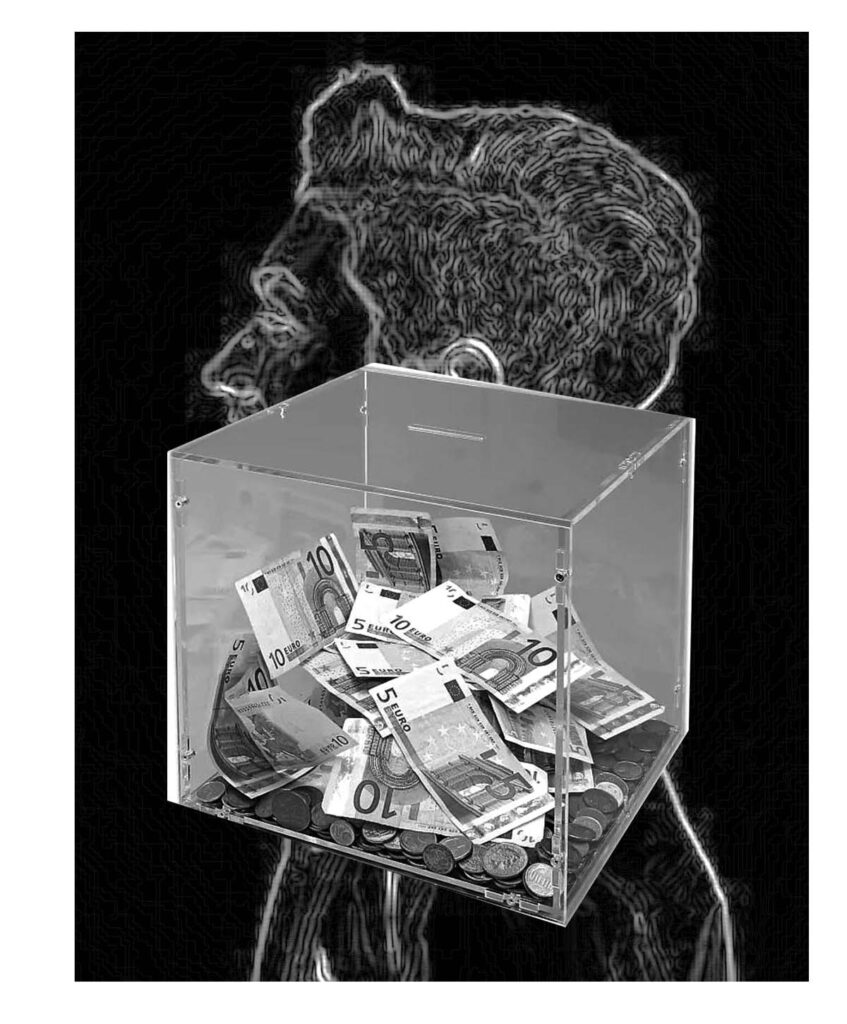

A huge tarpaulin stretched across the backdrop of the stage, adorned with greetings from a family of politicians, their faces plastered beneath the solemn image of Jesus Christ. Beside the platform, a wooden donation box sat still and unassuming, a silent witness to the spectacle about to unfold.

Amidst the crowded court, his attention was drawn to a jar of alcohol, within which long, silvery nails lay soaking.

The crucifixion usually started at three, but it demanded precision and rehearsal from its actors. Ezekiel watched as they gathered, murmuring their lines, adjusting their props, and slipping into their costumes. Shiny fabrics caught the light as the men transformed—some into Roman guards, their plastic armor clinking, while Kuya Jo and two others took on the solemn weight of Christ, their faces set with quiet determination. Amid the commotion, an organizer pulled Ezekiel aside, handing him the donation box and entrusting him with carrying it up the hill.

After rehearsals, the men retreated behind the stage for their usual dose of pain relief—a bottle of beer, a plate of sisig, and a glass of brandy, courtesy of the organizers.

Ezekiel handed Jo his crown of thorns. “Kuya, doesn’t it hurt?”

Jo let out a dry chuckle, stretching his arms. “It does.”

“But why do you keep doing it?” Ezekiel frowned, his expression tinged with resignation.

“Because this is how I talk to God. You know, praying means waiting, and I don’t have that kind of time. Faith is for those who can wait, but we can’t afford that.”

He patted Ezekiel’s shoulder and grinned. “It’s showtime!”

The small space quickly filled with townspeople, devotees, and tourists, all pressing in for a better view. The heat wrapped around them, heavy and unrelenting. On stage, the actors bellowed their lines with exaggerated passion, their voices cracking like dialogue of an old ’80s sitcom, raw, theatrical, and over the top.

The moment the verdict was announced, excitement rippled through the crowd. The guards, clad in red robes with golden breastplates, seized Kuya Jo by the arms and dragged him toward the village entrance. The wooden cross—the one he had painstakingly painted himself—was pressed onto his back, its weight forcing him to his knees. A mix of cheers and murmurs filled the air, mirroring the restless shuffling of feet, as the reenactment of his final journey began.

Jo staggered under the heat of the midday sun. His knees buckled, and the cross thudded against the dirt. He let out a shaky breath, his face contorted with exhaustion and pain. Ezekiel rushed forward, shoving a bottle of water into his hands, fanning him with a crumpled piece of carton. Jo took a shallow sip, then looked up at him, eyes dark, searching, desperate. A silent plea.

The crowd had thickened, a restless tide of bodies pushing in from every direction. Ezekiel clutched the donation box tightly against his chest as he squeezed through the devotees. Jo’s face was slick with sweat, the crown of thorns sitting crooked on his head, strands of his damp hair sticking to his lips. For a brief moment, their eyes met again. And though Ezekiel wasn’t sure, he thought he saw tears welling in them. He wiped a bead of sweat from his own forehead, the sun’s harsh glare making everything glisten, blurring the line between suffering and performance.

The rope meant to separate the actors from the crowd had long disappeared. The devotees, swept up in the act, began shoving Kuya Jo themselves. Their hands pressed against his shoulders, his back, forcing him forward.

Somewhere in the chaos, a small boy wailed, his cries sharp and panicked. He had lost his parents in the sea of people. Ezekiel saw him. And for the first time in a long time, he held someone’s gaze. He reached out, fingertips just brushing the child’s, but before he could pull him to safety, a surge of bodies came crashing in, swallowing the boy into the shifting tide of devotion.

In the distance, the hill came into view. Three wooden crosses loomed above it, casting long, skeletal shadows. The ground beneath them, made of lahar from the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, held the weight of buried secrets, remnants of lives lost, forgotten under the feet of those who no longer cared to remember.

Jo collapsed. The impact sent a heavy thud through the air. A cloud of dust burst around him, clinging to the folds of his robe, staining white to brown. The woman playing Mary broke character, her cries raw and guttural, as if she had truly lost a son. Veronica rushed forward, pressing her veil to Jo’s face. When she pulled it away, the pre-painted image of Christ was revealed. The crowd gasped in awe, their reverence shifting from pain to spectacle.

The donation box pressed heavier against Ezekiel’s arms. Blue and purple bills slipped through the slot, stacking one over the other. The weight of faith. The weight of desperation. The weight of something Ezekiel wasn’t sure he believed in anymore.

Ezekiel’s breath came shallow and uneven, his chest tightening with every step. The image of the lost boy flickered behind his eyes, but the crest of the hill was close now.

A Roman guard fell into step beside him, palm open. “The nails.”

Ezekiel dug into his bag and pulled out the jar, hesitating briefly before handing it over.

More tourists pressed in, their eyes gleaming with anticipation. Money slipped through eager fingers, vanishing into the box he carried.

The cross was raised halfway—just enough for the three actors to steady themselves on the wooden plank. A Roman guard poured alcohol over his hands, letting it drip between his fingers. Another knelt beside Jo, searching for the right spot in his hands. He pressed a two-inch stainless steel nail against Jo’s palm, feeling for the soft space between the bones.

Below the hill, where tourists huddled under tents and umbrellas, Ezekiel stood frozen. His hands trembled, his vision blurred at the edges. Tears welled in his eyes, and his lips turned dry, but he couldn’t look away.

Kuya Jo’s voice rang out, hoarse yet steady, carrying over the crowd. “Father, forgive them, for they don’t know what they are doing!” His breath hitched on the last word, strained from exhaustion, but his tone never wavered.

Ezekiel clutched the box tightly and hurried toward the exit. Tourists reached out, dropping bills into the slot as he passed. He kept his pace, pushing forward through the people.

He was near the exit when Jo’s scream tore through the speakers, the hammer striking the nail, each blow echoing across the hill. Ezekiel glanced to the side. Blood ran down Jo’s hands and feet, streaking the wood. His stomach twisted, bile creeping up his throat.

The guards hoisted the three actors into place. The crowd erupted into cheers and applause, their excitement swallowing a cry for mercy that never came.

Ezekiel found himself in the narrow passageway near their house. The stench clawed at his throat, thick and putrid. A sharp pain coiled in his stomach, rising fast until he lurched forward, emptying his guts onto the dirt. His breath came in ragged gasps as he wiped his mouth with the back of his hand.

He dug into his backpack, fingers fumbling until they closed around the screwdriver. He yanked the donation box to his side and wedged the tip into the seam, twisting, prying. The metal groaned but held firm. His grip tightened. A choked sob tore from his throat as tears burned down his cheeks, mixing with sweat.

He lifted the box and slammed it onto the ground. Once. Twice. Again and again, until the wood splintered, the lock cracked, and bills scattered like fallen leaves.

He snatched the money, stuffing it into his bag with trembling hands. Then, without looking back, he seized his bike and pedaled hard. The acacia trees blurred past him—those wretched trees, towering and unmoving, like silent witnesses to all he had ever been.

As the sun sank, devotees drifted toward their next destination, their silhouettes merging into the dimming light. Ezekiel slipped in among them, just another body in the crowd, just another soul seeking passage. On Easter Sunday, Ezekiel would be resurrected in a city where people wouldn’t know his sins.