“A week ago, just before you arrived, DongJosé,” my grandfather was telling me in between locomotive puffs from his rolled lomboy cigar. “A damn wakwak tore a hole in my nipa roof.”

I nodded as I feasted on my hot breakfast. I had arrived here in Canlaon, a northern town deep in the green heart of Negros Oriental, three days ago to spend Lent. Folks here didn’t wear face masks, and it was jarring for me at first to see dozens of bare mouths outdoors.

“Now I wasn’t keeping a pregnant lady here, was I?” Lolo Berting went on, letting out smoky fits of laughter. “I never even had a wife. Only women. And, oh, boy, what a number of them!”

Lolo Berting, this tuba-bellied, chain-smoking octogenarian farmer, who smoked lomboys for breakfast, was unmarried, and although known as the barrio womanizer, sired no children.

“Poor wakwak! Must have been starving it thought you were pregnant! You should have let it suck your belly, ’Lo.”

“No way, José. I keep a sundang under my pillow. I’d pull the wakwak’s tongue down here and cut it,” said this old man, slicing through the wisp of smoke with his non-smoking hand. “You don’t believe me, do you, José? That’s the problem with you city boys. You think you know everything. Take a look at that.”

So, I raised my eyes to where his cigar pointed. Sure enough, there was a hole up his nipa roof as big as a man’s fist. But anything could have caused it. Left to the elements, anything created by the hands of men crumbles down in the hands of nature…Then I went back to my favorite Visayan breakfast I couldn’t have in the city anymore—steaming sweet rice cakes wrapped in banana leaves, ripe yellow mangoes shining like gems, and hot dark-brown sikwate served in a bone-white sartin cup that was older than my skull.

“Better switch to tin roofs, ‘Lo. While you’re at it, let’s replace your bamboo and nipa walls with steel and concrete—ah, goodness, forget about the wakwaks! A typhoon can send your hut flying with them!”

“Dong José…” He shook his head and cluck-clucked his tongue. “People have been using nipa roofs longer than tin roofs. Even before Jesus was born! Even before the calendar was made!”

Such was this old man’s wisdom. Then he said:

“Dong José, did you know I once killed an agta for bothering one of my women? I buried him under this hut.”

“You killed an agta? How?”

“If you’re thinking of a fistfight, you’re an idiot. I dared the agta to a duel of riddles and won.”

“What were the riddles, ’Lo?”

“Maria’s hair, how fast it grows, and how fast it disappears. What am I?”

“Too easy, ’Lo. That’s for elementary school. Answer is smoke.”

“Creatures smaller than your nails climbing up the mountain’s trail. What are we?”

“Ants.”

“As black as the night, hmm…” Old age crept into his mind. He gazed at the hole up his roof where you could see a piece of the sky. “Ah! As black as the night, but soon turns white like light!”

After laughing at my ignorance for a minute, Lolo Berting finally told me the answer, and I was dumbfounded at how easy it was.

“How did you bury the agta, ’Lo? Did you chop the agta into pieces?”

“No, you fool. An agta shrinks into a midget when you beat him in a duel!”

We laugh the same way—full-mouthed, from the bottom of our bellies. He’s my father’s uncle,0 after all. Or my father’s other father since Lolo Berting and my father’s father were twins. If you’d put them together in a photo, you’d see triplets. Quadruplets, if you add me.

But neither my father nor Lolo Iping was the jester, Lolo Berting was. I only heard a joke from Lolo Iping once, and that was when he passed away in our home in Cebu ten years ago. While in the throes of heart failure, on his deathbed, he groaned, “I’d still be alive as long as my twin, Berting, is alive!”

As for my father, he hardly talked, let alone joked. My mother was only sarcastic, and my three younger sisters had the misfortune of inheriting their humorless genes. How many times have they cried from my harmless pranks! As any responsible brother should, I ratted them out to my parents about their crushes and boyfriends.

God knows why I inherited more qualities from Lolo Berting than from my parents, even though I only saw him once every two or three years. Maybe we inherited the same disease from one of our ancestors, whose belly had exploded from too much laughter: the inability to be serious about anything and the ability to joke about anything serious. Laughter is doubtless Lolo Berting’s secret to his boisterous good health and womanizing. If he were a pretentious writer like me, I could imagine him penning a verse like

What food is to a man’s heart

Is what laughter is to a woman’s

If you’re poor as a rat, worry not!

Laughter is not only the cheapest medicine

But also the cheapest aphrodisiac!

Other than passable good looks, I believe, humor was what landed me a jaw-droppingly gorgeous, scholarly girlfriend, a few years my junior, whose brains were bigger than her breasts, and a rear damn bigger than her brain. She came only close to perfect, though, because she was humor-impaired as well.

I smoked my freshly opened pack of red Marlboros. Lolo Berting hated how unnatural they smelled, so he recommended his lomboys. “Better this than that,” he said. “This is my secret to having a long life.”

I had to disagree. That one time I tried his lomboys, I saw death with my own eyes. I was bedridden for a day from migraine and nausea. It was worse than the worst hangover I had. I remember it getting so bad that I was hallucinating. I saw spirits walking in and out of the hut and talking with Lolo Berting while I was in bed, and that’s when I saw a dark-hooded tall man with a scythe. I asked Lolo if the man was Death, and he said, “What? No. He’s just a farmer.” Now I was tempted to tell him I had something better in my bag, which smelled and tasted like nature when smoked. I had bought it from a writer friend in Dumaghetto, whose name starts with a C and ends with an R, who secretly grew them in his backyard.

Lolo Berting’s nipa-thatched hut remotely sits on the edge of the Canlaon plains, where the ground starts to rise, so far from the barrio. Farther behind the hut is a narrow, rarely used trail leading up to the highlands where the guerillas battled against the Japanese Imperial Army. I wanted to go there after hearing World War II stories from my dear girlfriend, who was not only a reader of literature but also of history, a subject in which I was, to her great disappointment, illiterate. “And you’re four years older than me?” she’d say, her words laced with sighs and hormones.

So, for her, I had improved my reading diet. I made it healthier, more sophisticated. I dumped my sleazy Henry Miller books (I thought of burning his pornographic novels) and began eating through books that have class—books on local culture, history, and folklore, mostly from Dr. Resil Mojares, one of our favorite authors—and participating in local events, like the yearly Gabii sa Kabilin (Night of Heritage), where many historical sites and museums in Cebu are opened until midnight. Two years ago, we went to the Genocide Center in Cambodia and wept for humanity. A year after that, we visited the Cata-al World War 2 Museum in Valencia, in the far south of Negros Oriental, and stood beside bombshells bigger than our bodies put together. I came out from all of that a better man, and infinitely better at answering history quizzes.

But my love was mad I didn’t bring her here in Canlaon. We argued about it the night before my trip—post-orgasm. I didn’t have the nerve to tell her why. This town is too rural for her urban sensibilities. She was too sheltered from birth, and having a relationship with me, a long-haired college dropout, was her only rebellion in life. She only knew how to cook rice in an electric cooker. She’d scream at the sound of hot oil bursting. She’d fry a fish until it turns into what physicists called dark matter. I couldn’t ask her to climb up a coconut tree or ask her help to catch and cull a chicken. Instead, she’d cull me for bringing her up here.

Now Lolo Berting was also saying that these woods were haunted, especially now on a Good Friday, when evil succeeded in crucifying Christ. The unseen dwellers in the forest didn’t like strangers, more so if they came from another island, and even more so if the stranger came from Cebu out of all islands. There goes another reason why I shouldn’t bring my girlfriend here.

“Don’t worry, ’Lo. I’ll be careful, and be back for lunch, so prepare that chicken tinola for me. I’ll be famished as hell after this hike,” I said, giving him two thumbs-up and a stupidly wide grin. I climbed down his short hut ladder, passing over his smelly, noisy, chicken coop below, under which rested, in an unmarked grave, the remains of the agta that died as a midget.

Honestly, I didn’t share Lolo Berting’s unfounded beliefs and horrors. I had lived in Cebu City my entire thirty years without seeing any of the infamous kalag, agta, sigbin, tambaloslos, engkanto, tikbalang, duwende, and some such terms that needed italicizing. The idea of the supernatural, like God, was something I hadn’t really gotten used to when I reached the age of reason.

Once during a binge-drinking session, I heard a fellow pothead’s insight as to why we don’t see duwendes and white ladies in Cebu City anymore. Why? Because all the vehicles, especially trucks and buses, had run them over, and there were no hospitals for them, and the white ladies got tired of getting caught on smartphones and posted online. They might all have already migrated to smaller towns that still value peace and privacy. However, agtas were a different matter. This junk-eyed pothead got word they were still seducing, if not kidnapping or impregnating, pretty maidens. They take pleasure in disturbing lovers who are necking, French-kissing, and making out shamelessly under shadowy trees on a pregnant full-moon night, sending them running in fright, zipping up their jeans, and grabbing for, and sometimes leaving, their clothes. Some agtas even became voyeurs, caught peeking from tall trees at young women undressing in their condos. There were also stories of men whose testicles were swollen after pissing at a big old tree, or men getting lost in the forest for days only to be found hanging unconscious from a high branch. How could anyone, even those partially educated like me, believe all that nonsense?

“Just stay on the trail so you won’t get lost.” I heard Lolo Berting shouting from his window, his voice always carrying an undertone of laughter. I waved back from behind.

The forest bristled from the nine o’clock sun. No breeze came to soothe the land. Roosters crowed, dogs barked, cows mooed, flies buzzed, and I, a human being, complained about the heat. The ground was baked dry, cracked from the sun’s ferocious beating. It was so hot you’d think you were in the city walking on a slab of urban concrete with hundreds of cars passing by. Piles of cow dung lay like large dark brown cookies. Brown bone-dry leaves crunched under my feet.

I gave my backpack one last check. Inside were a big wrap of puto balanghoy, a water bottle, a book, a notebook, a pen, a wristwatch, and a dozen pre-rolled joints. I left my phone in my lolo’s hut, like what city people say they would do when they want to reconnect with nature. I patted my backpack. I was good to go.

When I reached the trail up to the highlands, I saw I was the only fool there. Even weather-hardened, flea-bitten mountain dogs were nowhere to be found. Off I strode alone into the sultry woods, with miles to go before I wept.

II

“Mama Mary Mother of God,” I whispered, careful not to be overheard, though my heart was like a toad trying to leap out of my mouth.

An hour into my hike, I found myself standing again and again in front of a gigantic balete tree. It stood almost as high and as wide as a three-story school building, covered with thousands of small, shuddering leaves and hundreds of overhanging, gnarled roots. To me, it looked like the perfect target: I had proudly taken a long, fearless piss at the balete tree.

Lolo Berting’s words had come to pass. Now I kept passing the same grove of trees only to reach a dead-end. The balete tree kept blocking my path, appearing in front of me whenever I blink my eyes too long. No matter how many times I turned away, I always returned to my piss mark that remained like a black scar on the trunk. My footprints had already gathered on the trail, both going backwards and forwards. Things were sinking in, so I reached down my pants to check if my balls were swollen. I was glad they weren’t. Otherwise, my girlfriend would have broken up with me to find another man, and Lolo Berting would have died laughing, and Lolo Iping would have died twice.

Shoving science and logic aside, since they were both useless in this situation, I put my bag down, took off my shirt, and wore it inside-out. When the spell didn’t break, I took off my underwear and pants and wore them inside-out. Then for good measure, I mouthed a yamyam Lolo Berting had taught me when I was a kid. Credo Jesum Christum Dominum Nostrum. I was also crossing myself, throwing in a mash-up of prayers I struggled to recall, like Our Father, Hail Mary, Glory Be, and the Apostles’ Creed. Quite ironic, since I was also an atheist in private, but a non-practicing Catholic in public. But what else could you do in such times? Still, as expected, nothing worked.

I believe pissing on a tree is a millennia-old practice we share with ancient humans. Even dogs, like their canine forefathers, lift their legs to piss on trees to mark their territories. So why do these other beings still get offended? Was my piss poisonous? radioactive? could melt the roots down to the ground? Isn’t urine, like feces, a fertilizer, too? Isn’t piss, after all, safe to drink? And, oh! how many times have I pissed outdoors in Cebu—in the hills of Busay, Sirao, Binaliw, Mantalongon—with nothing bad happening to me! Neither a toothache nor a bellyache! Besides, not even the police or barangay tanods apprehend people for pissing out on street corners, walls, electric posts, and wheels of a parked vehicle, even if there were no urinating signs—hell, has anyone gone to prison for pissing outdoors? The police even do the same when they have nowhere to go. No man is immune. But not here, where pissing rules must be religiously observed, even without signs, even though the culture of peeing outdoors had long been embedded among us Filipino men.

I should have taken the “charm” Lolo Berting had offered me yesterday. It was a black perfectly round stone no bigger than a golf ball. He said that it was an agta’s fossilized testicle, and indeed, it felt strangely warm to touch. It would ward off forest spirits. If an agta did bother me, squeezing the stone would send him running and screaming in pain. But I refused Lolo Berting so as not to give legitimacy to his story.

Feeling hopeless, I took heart from what Lolo Berting once told me: that these were just pranks from fun-loving creatures, no different from what you’d pull on your friends or siblings. All I had to do was just ask for forgiveness and permission to pass. And I did just that—to no avail. Nothing happened even when I promised never to set foot in this place again for the rest of my life. So, I thought a bit far out of the box. How about a little sacrifice? A ritual, maybe? What if I gathered my piss in the cup of my hand and offered a toast to the offended balete tree? Perhaps our ancestors did such a thing? No! I’d rather drink blood than drink piss.

I ran around for a couple more laps, calling out for help and getting back nothing but my own words, only to return to the balete tree each time. Daylight was now growing harsh, spilling through the balete’s shade from which birds chirped and sang. While eating my steamed rice cake, I had an idea: to climb up the tree so that I could get a bird’s-eye view of the forest. If I could map out the area, this illusion might fade.

I left my slippers and backpack at the base of the tree and started to climb without trouble. The entangling roots provided ample leverage and foothold. While climbing, my mind turned to the Beanstalk story I read as a child: at the top of the tree, there lived a giant. Such thoughts distracted me, and my foot slipped. With two hands, I pulled hard at a thin root to keep myself from falling.

Then the balete groaned as if waking in pain. Its leaves shuddered, and its trunk of twisted roots untangled and opened into a dark gaping mouth smelling like the dung of a thousand cows. The roots wrapped around my hands and hurled me into the mouth of darkness.

III

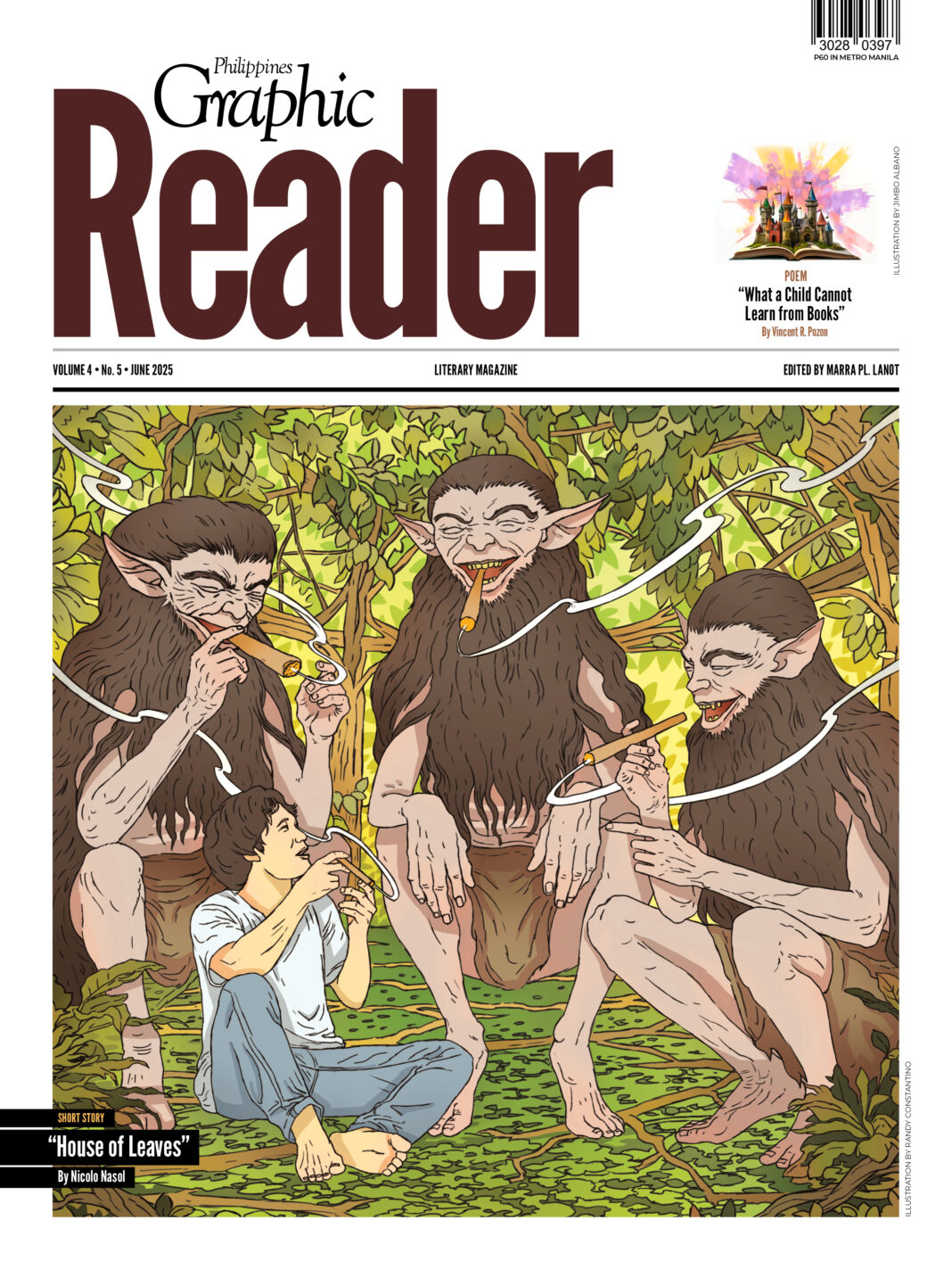

“How did you get in here?” It was a booming, drawling voice. To my relief, it spoke in a Visayan language I could understand.

I rolled over my back and saw, amid the blurry green background, three hulking shadows blowing clouds of smoke from their mouths. Smokers of sorts would find the cigar aroma pleasant. It made the smell of cow dung bearable. I groggily sat up, my hands brushing my eyes.

When my sight settled, I realized I was in a massive room in which I was as small as a mouse. It was floored, walled, and roofed with nothing but leaves. But not the dried, dead leaves you see in huts, but green, blooming leaves teeming with breeze and sunshine.

I looked up to see the agtas. I had little doubt they were them. But I never thought they were this immense. They nearly stood as tall as street lamps. Rolled cigars bigger than my arm burned and dangled from their thickly bearded faces. Thick long hair twirled in knots. Eyes the color of earth and wood. Their mouths, however, bothered me a little: an entire human being, unless too fat, which I wasn’t, could fit in there. But I hardly felt any alarm, for I had the riddle Lolo used to beat the agta. It was a matter of pride among agtas never to decline a match from a mere human being.

“Hey, Boss Gomez was asking you, how did you get in here?” asked a voice not as menacing as their boss. “Get up or we will eat you,” said another voice no more menacing. “Quit it, Burgos. You, too, Zamora!” roared the boss.

Gomez? Burgos? Zamora? I studied their dark hairy faces. Who was who? The largest for sure was the boss, Gomez. Either of the smaller ones was Burgos or Zamora. They looked as identical as two leaves of the same size from the same tree.

They all bent down to take a good look at my face. I put my head down. The dung odor got too sharp in my nose and knocked me out of breath.

“Hmmm, sort of a good-looking human—damn, I knew it!” I heard Gomez say. “Call Toyab, now!”

The other two bellowed “Toyab! Toyab!” so loud the leaves in the room and my entrails inside me shook. When I shouted, “Toyab!” Burgos and Zamora glared at me.

The floor of leaves parted like the red sea, and another agta climbed up. He was now the smallest among the group. Gomez smacked his head, knocking the newcomer back to the lower floor so he had to climb back up again. “I told you many times never to do it again. We don’t want any men in here. Only women. Oh, for Bathala’s sake.” He bellowed a command, and the parted floor of leaves joined back together.

“I’m sorry, Gomez,” said Toyab, touching the sore spot on his head, which barely reached Gomez’s belly. “He had pissed at our home, and that made me mad! But, my, he’s so good-looking and amazingly endowed. What a waste to make his balls swollen! But how did he get in?”

Strangely enough, Toyab sounded gentle. His eyes held no anger at me. But what struck me most was that he had fair, hairless brown skin, unlike the rest of them. Toyab had no beard at all, in fact, even more clean-shaven than me, and his long hair was silky, straight, and shiny and dropped to the sides of his head and swayed when he moved.

Toyab sat in front of me. The others remained standing, scratching their muscular furry chest, gazing at me while cozily puffing smoke. Since they were all silent, they must be deciding over my fate, so I stood, seeking Toyab’s comforting eyes while awaiting their verdict. Toyab pulled a cigar from underneath his bahag, or loincloth. It was way smaller compared to the other three, merely a quarter of Gomez’s cigar.

I took the little box of matches from my pocket and said, “Dagkot?” That made Toyab flinch. Why not offer him a light? I was doomed, anyway.

“Aren’t you scared of us?” asked Gomez, blowing the smoke right at my face, fragrant with the smell of leaves, wood, nuts, and bits of fresh earthy soil. Not wanting to sound arrogant, I nodded at him.

“We haven’t seen you here,” Gomez went on. “What’s your name?”

“I’m from Cebu. My name is Henry Mojares,” I said, coughing to keep myself from laughing. “Can I ask a question?”

“Is it about our human names?”

Toyab bent over to me and asked me to light his cigar. I struck a flame and raised my hand. When it caught fire and smoke, he smiled at me and said thanks. Toyab looked at Gomez, and Gomez nodded.

“A priest had given them those names,” began Toyab as I sat back down. “He was one of the many civilians abducted by the Japanese during the war a long time ago in Cebu.”

You could have heard my jaw drop and my heart stop dead for a few seconds.

“They became friends with the priest. They were baptized, for the priest was so thankful. Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora hid Cebuanos inside the trees and helped ambush Japanese soldiers. That was Babag in Cebu, right, Gomez?”

“That stinking city!” the smaller agta growled. “Stinking city!” the other echoed the growl.

Gomez’s raised hand silenced the room. He spoke, “We three spent hundreds of years living there until you people cut down our trees ten years ago. I was mad at first, but we were moving out, anyway, here, closer to our Grandmother Balete tree.”

“You mean the Dakit?” I asked. “The gigantic thousand-year-old tree?”

“That’s what you call it, yes,” said Gomez, blowing perfect rings of smoke, to which the other agtas applauded. “Things weren’t looking good for agtas in Cebu. Our brothers there are stressed out and raving mad, so they caused floods and made typhoons stronger. How’s that virus thing going in your place?”

I was too stunned to answer. When I didn’t say anything, Gomez asked me about the massive reclamation project off the coast of Dumaguete. I tried to speak, but no words came out of my mouth and tongue, even though they were moving.

“You people never learn,” said Gomez, shaking his head. “Don’t be surprised. We’ve been keeping up with the news ever since Father Ibarra taught us more about humans. Rumors get around here faster than you think. The trees have eyes and ears, as we used to tell each other here.”

Burgos and Zamora were whispering to each other. Toyab’s cigar was nearly burned out, so he took another one and asked me to light it. It was strange because the other cigars weren’t even close to burning out.

“Ah,” said Toyab, “I am still not that good at making cigars. Theirs are way better, especially Gomez’s.”

I took out my matchbox, along with one of the rolled joints I happened to keep in my pocket. After I lit up Toyab’s cigar, I quickly lit up mine. I could see they were watching me with interest.

“Those don’t look like ordinary cigarettes,” said Toyab. I said it was one of nature’s medicines. “Medicine to what?” asked Gomez. “Sadness,” I said, pointing to my heart. That made them laugh, even Gomez, who was the last one to stop.

I smoked and took my time with each drag. Mid-joint, with the effects settling in, I began answering their queries about the outside world: “There are fewer cases now, around fifty. That’s a relief since we had to go through a surge of thousands of cases just a few weeks after Odette.” I took the next puff too deep, and I coughed like an ailing grandfather. I brushed away their worries, and told the agtas I was fine. “But worldwide, the pandemic seems to be set to infect the entire population. The vaccines are working, but most people’s minds aren’t. With the way things are going, another million or so are expected to die. But experts are hopeful after the latest Omicron wave. It’s a weaker variant. My entire family had it last January, but we were all vaccinated. I had it, a deadlier variant, a year ago. I thought I was going to die in our home…”

The calm of mind was kicking in. I was ready for deeper thoughts. I was on fire, but it was the kind of fire that’s burning underwater. I couldn’t show them how I was feeling.

“The pandemic sounds familiar,” said Gomez. “We heard stories about it from our elders—”

“Regarding politics, the son of the dictator Marcos seems to be leading in surveys—”

Gomez growled, glaring at me as if it were all my fault. “How stupid can you people get? Illegal logging was rampant during his time. Thousands of our kind were forced to move out. More than a hundred wanted to join the rebels and overthrow Marcos, but our elders stopped them. It was not time yet to get involved.”

I thought I was so high I wasn’t hearing things right. “Oh, shit. Is that true?”

He took a puff from his undying cigar. “You don’t believe me, Henry Mojares? Why are you laughing?”

“No, no, sorry. Just call me Henry, for short.” I knew I’d tear my belly laughing if he called me by that name again. “I never knew. I have never read in any book about agtas wanting to join the rebels. And to be honest, I’ve never believed you were real.”

“Now you know. You think you are all that this world has, Henry?” said Gomez, me a prisoner in his glare. I noticed, too, that the other agtas were also glaring at me.

“I apologize for humanity!” I must have been quite stoned already or too overwhelmed since I kneeled down and kissed the leaves on the floor, bowing to them, begging for their forgiveness.

“Pull him back up, quick,” said Gomez. He was shocked or embarrassed to see me crying.

Toyab pulled me back up, gently so as to not break me, and asked me what I had been smoking.

I told them what it was, adding, “If you want to try, I have some other joints in my bag, which I left outside.”

Gomez gestured for Toyab to go out of the tree. The walls of leaves split open, and Toyab jumped out. No sooner had he jumped out than he jumped in with my backpack and handed it to me.

I gave them one joint each. They looked like toothpicks in their hands. I taught them how to smoke it. “Inhale slowly, swallow the smoke for a while, and let the smoke rise up your mouth.”

I lit their joints, and they smoked them in one go. They coughed and coughed like consumptive giants. Their breath still reeked with cow dung, but I had gotten used to it.

“Shit. What is this?” said Gomez, a bit shaken up, eyes widening.

“You’re tricking us, are you?” said either Burgos or Zamora.

“How could you—”

“But wait. This feels nice,” said Gomez, feeling its effects strongly as a first-timer would. “Do you still have some?” A smile gleamed in his face like a knife.

I gave them the rest of the joints, and they all smoked one under a single breath.

“I bought these from a friend when I got here. He’s from Bacolod, a bit far from here.”

They were laughing, nodding at me, without listening to me. Their bodies had loosened up so that they lay down on the floor of leaves like dogs. I told them they shouldn’t smoke it outside since they might fall off the tree.

“If it grows anywhere in this forest”—Gomez, spread-eagled on the leaves, pinched the last of the joints and smoked it—“we can get some and make cigars.”

From my bag I took out a notebook and drew it for them. “Its leaves are shaped like human fingers, as if to say they were made for humans.” I was telling them how to prepare it when Gomez cut me off.

“We’ve been rolling cigars even before you were born, Henry, even before your grandparents were born. Ha-ha!” Then Gomez took my notebook, looked at the drawing, and passed it to Toyab. They told them to go find the plant and bring back as many leaves as possible. Too excited himself, Gomez had forgotten what he said and joined them in the search. They jumped through the walls without even waiting for them to open. I was left alone in this room to reflect what had become of my life. I checked my watch. Its hands hadn’t moved since I got in here. I remained sitting as still as a tree on a windless day. Having brought no book, I read an imaginary book in my hand.

After a while, the agtas returned, breathless, bringing with them different handfuls of leaves, asking me which one it was.

“We nearly got seen,” said Gomez, laughing with the others. “No good roaming around in daylight.”

These agtas must have stolen them from other planters. But, alas, I found the one and only! I told them to hang it outside under the sun.

Gomez blew his breath on the leaves, and suddenly they were dried and cured. “Like this, Henry?”

I was amazed. We could start a factory—no, an empire—right here and get rich. Agta-cured pot. I would quit writing and be an entrepreneur. Become a millionaire. No, a billionaire!

Together the four of them got into the process of rolling the leaves into cigars, and they were thoughtful enough to make a couple of human-sized rolls for me.

“Bring in the jars of tuba,” Gomez said to his crew, when they were close to finishing their job. “And don’t forget to bring a small one for Henry. Burgos and Zamora, roast goats for us. Quick.”

It was turning into a feast. For what? I wasn’t sure. But we were smoking, drinking, eating, and laughing. You’d think we were old friends. I remember Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora talking about the most beautiful women they had ever seen. A few of them were actresses. Then Gomez walked toward a corner, pulled down his bahag, and took a long piss.

“This is good stuff. I never saw anyone here smoking this,” spoke Gomez, in the middle of pissing. He went back to his seat.

“It’s illegal in this country,” I said.

“Why?” asked either Burgos or Zamora. I could never tell, for it just dawned on me they might be twins.

“Long story. But I believe we can manage. I have friends. Besides, if you get caught, you won’t fit in jail. Ha-ha! You’ll scare the other prisoners. Besides, the human laws don’t apply to you.”

“Ha-ha! Maybe we could trade these to the other agtas for plots of hills with bigger, older trees,” said Toyab.

“That’s a good idea,” said Gomez, gulping down a jar of tuba and taking a bite of an entire roasted goat.

We continued to feast, exchanging stories, smoking joints, taking a bite of goat’s meat, drowning ourselves in tuba. Our joints never flamed out. They have now glazed looks on their eyes like my friends used to have. I never knew agtas were these nice creatures.

Then it was only me and Gomez left awake. The sunlight outside had long turned dark. The others had dropped off to sleep, sprawled on the leaves, snoring.

Gomez spoke after a long silence. “You say you’re a writer, Henry?”

“Yes, a very bad one!” I laughed because it was true.

“To show you our gratitude, I would like to share with you a story about our world.”

“Go shoot, I am all ears,” I said.

IV

Gomez began his tale: “Our Grandmother Balete tree once stood at the peak of these mountains and reached the clouds. I’ll tell you where it was once later…” He stopped to take a puff and a gulp, but perhaps thinking they were a distraction, he snuffed the cigar out on his palm and set aside his jar.

“Where was I?” said Gomez, burping. “Oh, humans back then looked more like us and less than you, although they were too small compared to us agtas. Ha-ha! They lived on the hills far below us, but they offered us fruits, wine, boars, goats, and pigs. Mind you, we were treated like Gods back then! In return, we choose one among them and give that person powers to help them.

“And one of the chosen ones we remember fondly was the little girl Sawag. Why was she chosen, you ask? Well, she was the only one who dared to climb up the tree that reached the clouds, even though she was only a child, and it was forbidden by all villages to do so.

“As this story goes, the agtas watched her climb as high as she could. When she reached the clouds, strong winds blew her off the tree. But an agta leaned out of the trunk just in time and caught Sawag and brought her inside.

“Sawag stayed with them for a long time until she learned how to use the powers that they had given her. They asked her to be a healer when she returns to the village, and that’s what she did.

“They kept watch over her and were happy to see Sawag was putting her powers into good use. She made the sick healthy, the mute speak, the blind see, the limp walk, but she never brought the dead back to life—that was forbidden. While the other healers used roots, seeds, leaves, potions, animal sacrifices, and incantations, Sawag only used her own spit, words, and hands. She was that powerful.

“A long, long time passed, and the agtas realized how dearly they missed Sawag, that one day, they lost the will to roll cigars. They saw Sawag growing old and wrinkled but happy. Still, this saddened the agtas, so one night, they took her away from her nipa hut and brought her back. When Sawag got inside the tree, she turned into a child again. They told her that if she goes out, she will die. If she stays, she could live as long as she wants.

“Along with the agtas, Sawag kept watch over the people. And each time one person dies from a sickness she knew she could heal, Sawag cried. When a plague hit the villages, with people dying from it every day, Sawag never stopped crying.

“Before long, Sawag argued with the agtas, asking them to let her return to the land. That she’d rather die than watch her people die with her doing nothing.

“Angered by Sawag’s ingratitude, the agtas threw her down the tree. But the agtas were crying themselves, and never stopped watching over her, protecting her, in ways Sawag didn’t notice.

“The agtas knew that the plague would kill everyone of Sawag’s kind. But they wanted to save Sawag. They realized that the only way to save Sawag was to save her people as well.

“And so, from the top of the Grandmother Tree—this is the ancestor of the Dakit—the agtas together bellowed, ‘Sawag, Sawag! Bring everyone up here.’

“After three days, Sawag, old and ailing by now, brought what was left of her entire village, and they were all children.

“The agtas stepped out of the tree and explained to the children that the human world will soon end, that once that happens, the animals, trees, plants, and creatures like them will once again reign over the land. If they want to survive, they have to live inside the balete tree until they become agtas. But for their powers to work, one child must be left as a sacrifice.

“Sawag, without being asked, said she would be the one staying, and asked the agtas to please save all the children. That broke the hearts of the agtas, but Sawag smiled at them and thanked the agtas for everything they did for her.

“The roots of the balete tree split open, and Sawag hugged and kissed each child before they entered. The agtas stayed beside Sawag until the day she died and buried her at the base of the tree.

“To honor Sawag, the agtas decided that when the time is right, the trees will split open, and from the split trunk, the children will be reborn to populate the land again…

“And that’s what happened. When the time came, the ground shook as if it were about to explode. The trees split apart, giving birth to people as dark as the agtas but smaller. But the birthing shook the land so much that the island’s burning blood burst out where the Grandmother Balete was, and it became this island’s volcano.”

“Goodness,” I said, trying to keep my eyes open after an unexpectedly long tale. “You mean that’s how the Kanlaon Volcano was born?”

“Yes, Henry, it is…” Gomez was suddenly drifting off, too.

As if the story had both exhausted the two of us, we joined the others in their sleep.

V

“José, José.” I heard my name. Then I woke up. Someone’s hands were shaking my shoulder. They were cold, and they were Lolo Berting’s. He was standing over me, smoking his infinite lomboy cigar.

“What the hell? How did you get in here?” I sat up, thinking that I must have been dreaming, squeezing my cheeks, checking if they would stretch before me like rubber.

“You fool, don’t act as if you live here! I saw your slippers outside”—he threw them at my face—“so I went in. I was looking for you,” he said, puffing smoke. “You were gone for a month, Dong José. And what’s that smell? That’s no cow dung—”

“What? A month? Who won the elections? But before that—a month?”

“Yes, time runs differently here. A day here is a month outside. Your family in Cebu is worried. Your face is all over the news now. They thought you were kidnapped by the New People’s Army rebels.”

“Oh, god!” What else could I say? “Oh, god!”

My screaming awakened the sleeping agtas. They yawned, stretching their bodies. Toyab’s legs nearly hit me, but I managed to jump out of the way. It was only Gomez who stood up, groggily, shaking the cobwebs of sleep and hangover off his head. He smiled when he saw Lolo Berting.

“Hoy, Manong,” said Gomez, getting another cigar from his bahag and blowing fire into its tip. “Long time no see. Got a riddle for me? Wait, you look—”

“Just taking my grandson home,” said Lolo, laughing as loud as ever, winking at him. “Hope you had a good time together.”

“I see, your grandson. That’s why,” said Gomez, overflowing with mirth. I realized for the first time that his laugh sounded like Lolo Berting’s and mine. He turned to me. “Thanks for the new cigar.”

“What cigar?” said Lolo.

“No, no,” I said. “Let’s just go out. Bye, Gomez. Say bye to everyone. I still don’t know which one is Burgos and Zamora.”

“Doesn’t matter. They’re twins.” Gomez bellowed a command. The wall of leaves split open, and I could see the world outside as though from a window.

“Before you leave, take this.” Gomez handed me a small black stone, similar to what Lolo Berting showed me the other day. I took it. The stone warmed my hand. “Bye, Henry Mojares.”

Before Lolo Berting could ask about the name, I picked up my backpack and jumped into the darkness.

In a flash, I was back outside the great balete tree. It seemed late at night, for the air chilled my bones, and a swarm of fireflies gathered around the tree, a hundred eyes of light blinking, and leaves teeming with life in the night. The fireflies, the stars of the forest.

Lolo Berting jumped out after a few minutes. He smacked my head as soon as he landed. “You fool, you damn fool!” But he was laughing. “Glad to see you safe and sound.”

“I have to go back to Cebu right now. My family, my girlfriend—”

“Don’t worry,” said Lolo Berting, tapping my back. “It’s still Friday. You were just gone for hours.”

“Damn, old bastard!” My cry echoed in the woods. I pushed him and almost kicked his fat belly.

“You believe me now? Oh, for sure you do.”

“No, I still don’t,” I said to him, wiping my eyes. A man is only allowed to cry at weddings or funerals. “No, I don’t…how did you know them, ’Lo?”

He showed me the black stone from the previous day. I laughed as I showed him mine and told him we now have a pair of agta balls.

Off we walked. Along the mesmerizing woods, lit by the moon, stars, and the line of fireflies following us and lighting our way, we saw agtas sitting on their branches, smoking, waving their hands.

“Found him already, Manong?” shouted one of them.

“Yes, thanks, Rizal! You’ve been a great help.” Lolo Berting waved back at one of them.

Then a gang of engkantos, wakwaks, tikbalangs, kalags, duwendes, and some creatures I had no idea existed popped out in between the rows of trees, telling Lolo Berting they were glad that he had found his grandson.

“Still don’t believe me?” said Lolo with a smirk on his face.

“Still don’t,” I said and lit a rolled joint I had kept for myself. “Still, I don’t, ’Lo. Still—” I stopped, realizing that the old man seemed different now. “Hoy, ’Lo, why are you so pale? You look like a ghost!”

For the first time in my life, I saw Lolo Berting’s face get serious: his mouth shut tight and his eyes turned as inhuman as black coals. In the entire minute that he was somber and stone-faced, my heart broke as quietly as it could. Then he let out his usual bellow of laughter that broke his stony face. I wondered if a tear fell from my eye because I kept wiping my cheek. It must be the moonlight bouncing off his face that made it look white, cold, and as ghastly transparent as glass. I put my arm on his shoulder as we walked back to the edge of the barrio. Behind us, you could hear the entire forest of Canlaon, the thousand houses of leaves, shaking with laughter.