As we count the months, weeks, days, and hours to the centennial year of the Philippines Graphic in June 2027, we will walk down memory lane. With every issue, we will present to our readers snatches of the distant past—captured in reprints of Graphic stories, editorials, columns, illustrations, and photos published during the first five decades of the magazine. It is our way of showing to our readers how unresolved issues and concerns travel across time and plant themselves squarely in our present and future. Hence, the need to learn. In the words of George Orwell: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” —Ed.

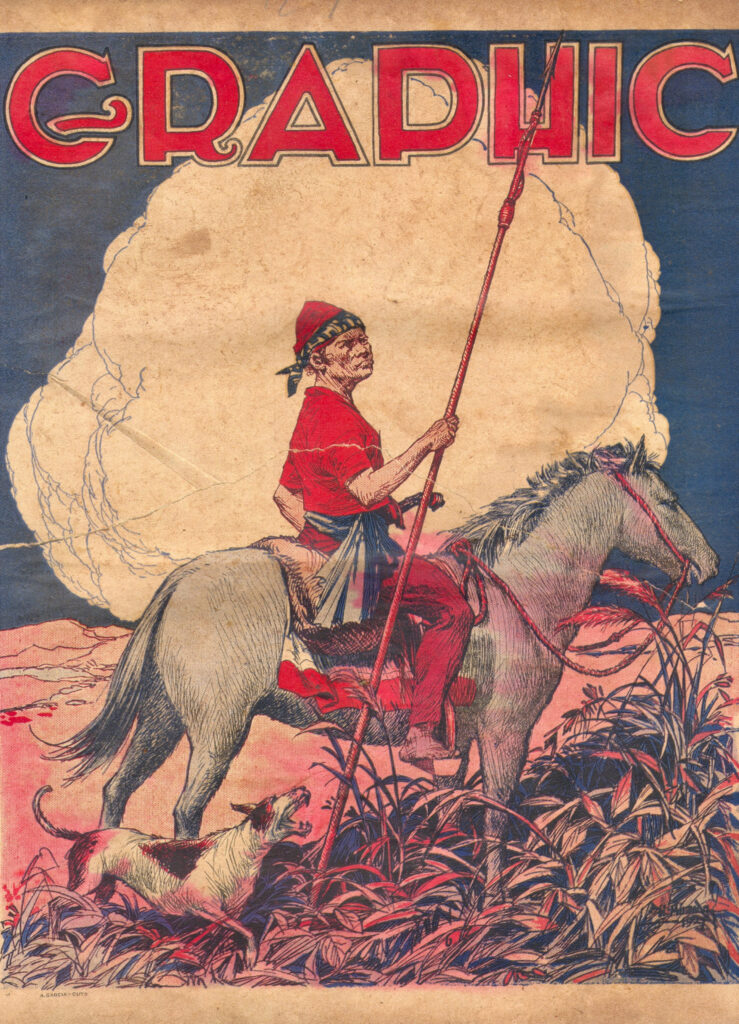

It was the 30th of July when I finally found the first-ever Graphic issue. Amid the careful sound of shuffling pages in the background that ran against the noise of my mouse clicks, I was sure that I paused for a long time admiring the cover displayed on the screen—dashes of striking red on the clothing of a Mindanao man riding a horse.

I had to stare. I had to take it in and remember it. It’s a moral obligation to do so.

Two years away from its hundredth year, the Graphic has survived many catastrophes in its long, long life. One of its most persistent enemies, however, is time and the annoying illness that goes with it: forgetting.

Nowadays, we have a myriad of ways to suppress the growth of this illness. For one, we take photos of everything.

Taking photos in the earliest years of the technology used to be limited. One has to wait for a long time to take a photo.

But the instantaneous and pervasive nature of photography had made it possible for us to capture everything we desire to capture—from the most special to the most mundane, from the fleeting moments to an entire event.

The special quality of photos to freeze time caught the mind of Graphic’s original publisher, Ramon Roces.

The magazine’s inception stemmed from his desire to have an “up-to-date illustrated weekly, one devoted almost entirely to pictured news.”

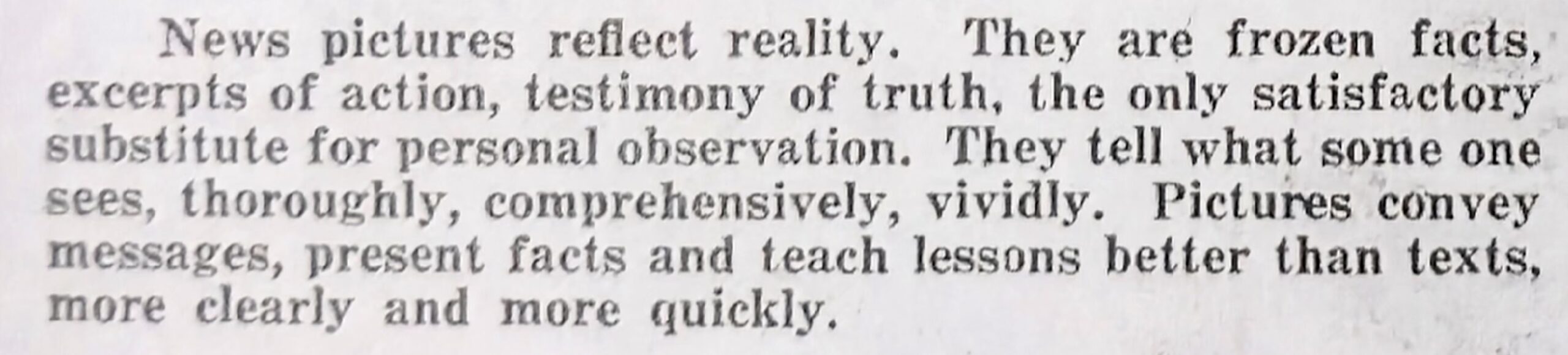

He wrote on the first page of the maiden issue:

“News pictures reflect reality. They are frozen facts, excerpts of action, testimony of truth, the only satisfactory substitute for personal observation. They tell what some one sees, thoroughly, comprehensively, vividly. Pictures convey messages, present facts and teach lessons better than texts, more clearly and more quickly.” — Ramon Roces, original publisher of the Graphic, 1927

A picture used to convey the truth. It was one of the most definitive references to the truthiness of any event for almost a hundred years.

It used to.

With the rise of generative AI over the past few years and how easy and accessible it has become to manipulate an existing image or, worse, create a convincing image out of nothing but someone’s imagination, the authority of any image now becomes questionable.

It is no longer the “frozen facts” that Roces once proclaimed it is; it can now be thawed.

And if the past could be melted down and reformed into another shape, what becomes of us in the future?

Will the future even know us for what we really are and how we really lived and existed, with impeccable exactness and veracity?

Photos, which mankind has invented to combat the illness of forgetting, have become a way of forgetting.

It used to “re-present” reality, in the sense that photos bring back what, at one point in time, was once “the present” into our present.

Now it can “de-present.” It undoes the past into something that someone wished it to be.

It is no longer remembering but disremembering—the literal butchering of what really happened.

And what more to the physical pieces of our past—records, old photographs, old clippings, and magazine issues—that are subject to the gnawing of time?

If libraries, museums, and archives had never been thought of, we would never have a clue of the time outside of our own. Alas, any generation permanently remembers only what it had lived through, and nothing else.

That is why I had to stare at the cover of the Graphic’s maiden issue and all the pages that followed it. That is why I had to take it all in and remember it. I owe it to all those who kept it alive for almost a hundred years.

Because the things that we keep in the archives are the things that we have the obligation to keep in our memory.