I attended an awarding event once where I saw firsthand how a group of respected writers interacted only with those they deem worthy of acknowledgement. They clapped only to the people they know. Many of those in attendance were a bit new to the scene; they did not know the people around. They were more like outsiders, divided by an invisible wall of exclusion and status. Until the end of the event, the well-known group acted as if they were the only ones there. The rest were silent—a shy smile here and there, compelled to remain in their seats. No unity among them; just cold partitions.

The giants stood with their smiles, but kept their distance as they did so. The pretty names of the writing world did not approach those unfortunate who had to go home empty-handed.

I stood from a distance and the division was clear. In that moment, writing seemed more like a privilege than it was freeing.

So when I heard the news that the Solidaridad bookshop—formerly owned by the late national artist for Literature, F. Sionil Jose—was up for sale, the uncertain future of one of the most important spaces in Philippine literary history terrified those who knew about the establishment’s historical importance.

More than that, I feared that the potential loss of such a space, which broke the division I saw at the awarding event (which will remain unnamed), to the fangs of commercialization, will further push us away from having collaborative and communal milieu for writers, thinkers, and readers to throw their ideas around.

Though Solidaridad clarified a day after it announced about the sale that there had been a miscommunication and that negotiations were still ongoing, it did not bring any huge sigh of relief among those who knew the historical importance of the place.

Its fate didn’t change—it was still about to get sold.

Ever since Jose’s passing in 2022, the transition in ownership might have become more of an inevitability than a possibility.

“If we didn’t own the property, Solidaridad wouldn’t have lasted ten years,” the national artist’s eldest son Antonio “Tonet” Jose told Philippines Graphic.

Apart from the attendant who was keeping watch, there were two or three people there when I visited the place, browsing the aisle of books in the air-conditioned space.

“Sometimes I would hear them [the customers] discussing books,” the younger Jose said. He smiled at his own remark, pleased by the youth’s interest in the books that populated his father’s bookshelves.

But the real world exacts a high price. One could only do so much to keep things afloat. Had the building not been their property, the rent alone would’ve made the hardship twice as hard.

“Before, we close at 7 [p.m.],” he said. “Now we close at 5.”

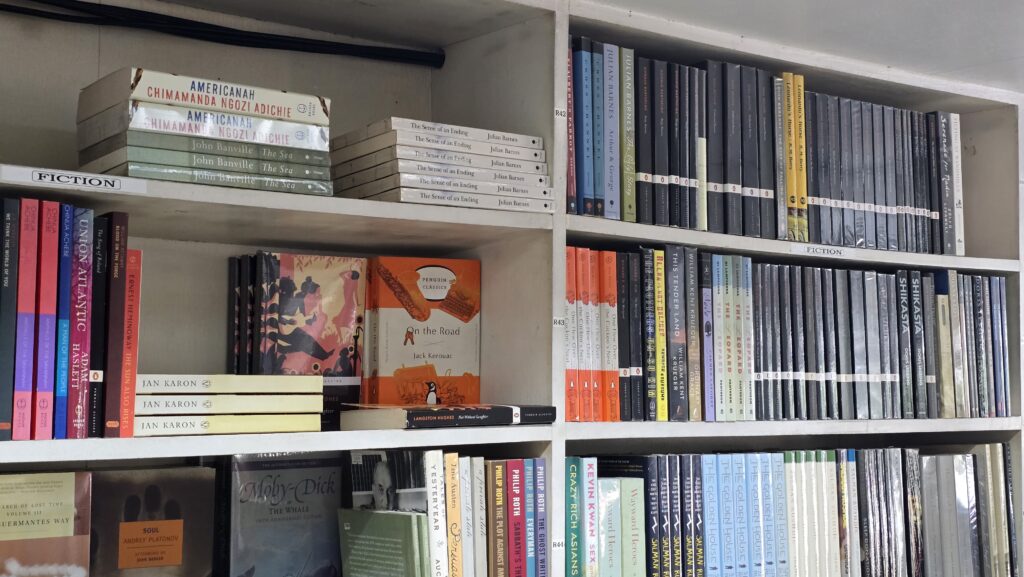

Books of all kinds from all over the world populate the shelves of Solidaridad

The bookshop became hard to sustain. When the pandemic struck, it saw some of its most difficult days.

“There was no profit during the lockdown,” Tonet said. “And then when it opened, none—still weak. People were still scared to go out.”

We sat around the famous roundtable where a lot of dignitaries, thinkers, leaders, and the “who’s who” of this transitory world sat before me.

“If this roundtable could speak, there’s a lot of stories it could tell,” he said. “The people who had sat and discussed things here [were politicians, Nobel Prize winners, and literature professors.”

According to Tonet, the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, who won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature, had graced the spaces of the saloon. As did Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer, and a member of a royal family who, according to Tonet, ended up late at her courtesy call to Imelda Marcos because she enjoyed her time at Solidaridad a little too long.

There were times back then when the Egyptian ambassador would visit the book nook primarily for the music. Classical masterpieces would play over the speakers, like it still does now, while customers browsed the aisles, with their eyes gliding over the book spines.

Nick and Jose

F. Sionil Jose’s office, where he spent his time writing, is also a place where discussions would happen if there were only one or two guests

The bookshop’s name meant “solidarity” in Spanish. Indeed, it was what the bookstore—and F. Sionil Jose—stood for.

People of all walks of life and from all places go to Solidaridad looking for kindred souls. They walk around the shelves and, no matter their differences, hear the same music and browse the same aisles. There were those who gathered around the revered roundtable, sat on the chairs, lounged around the saloon, and discussed ideas.

The conversations that bounced within its walls could either make a man or build a country. Arguments were lunch and dinner in the saloon; it was inevitable, especially when ideas clash, which often do.

Tonet and his siblings were used to hearing shouting matches as their father and some of his guests would debate over a lot of things. It frequently happened with one of his old man’s closest friends—fellow National Artist for Literature and former Graphic editor-in-chief Nick Joaquin.

“He comes here,” Tonet recalled of Joaquin. “Doon sila naguusap sa kwarto. When he comes here, dine-dread namin yon, dahil for sure, uwi kami gabi. When they argue with each other, sigawan silang dalawa, to the point na naririnig mo sa baba.”

[He comes here and they talk in the office. We dread it, because for sure we’ll go home late. When they argue, they would shout at each other, to the point that you can hear them downstairs.]

A photo of Nick Joaquin and F. Sionil Jose hangs on the wall of Solidaridad

But it is in arguments like such that ideas foster. When contested, they sharpen one another. A once seemingly weak proposition, after rounds of discussion, could topple down an empire or bring about enlightenment.

Writers, no matter what the institution or country that shaped them, came to Solidaridad for the space to discuss life and human nature, and Filipino identity, alongside jazz, plus politics and freedom, with individuals who, though they might not share the same thoughts, they do share in passion.

The saloon at the third floor of the building congregated some of our greatest thinkers and their sublime thoughts. As Tonet continued telling me his stories, the more that I wonder if this very building naturally attracted those who can enact change in the world.

“Rizal used to come here. My great grandfather [was his classmate],” he shared, as she talked about the building that belonged to his mother’s ancestors. “He would come here, pick up my great grandfather [but he never comes into the house because he was already an activist then]. He would wait outside and would just go around.”

Solidarity standing

For the many decades that the building stood, it was more than just a bookstore with an office space on the second floor and a literary saloon on the third. Though there might not be solidarity in the ideas conjured by those who came there, there is clear solidarity in their goals: the betterment of the society.

Or there was.

Concern was widespread in the literary community when Jose’s family announced that Solidaridad was being sold. But in equal measure was the hope that whoever buys it will respect the establishment enough to protect it.

Though the establishment did attract thinkers, writers, and powerful people toward it, so too were seminars and events that happened frequently all over the country. It was, to say the least, common in that regard. One could argue that events such as the Palanca Awards and the Nick Joaquin Literary Awards aim for the same thing.

The beauty of Solidaridad, however, does not require a ticket or invitation to be in the same space that the big names of our society frequent. It did not need a person to have contributed something grand to visit Solidaridad, necessitated for a manuscript to be submitted, or for a fee to be paid.

It did not matter if you had a Nobel Prize or if you ruled over a country, and it did not matter if you published 10 books, or you’re just starting out. It did not ask if you were working a 9-to-5 job, or you were a millionaire. The only thing common to its long guest list was that they could think, that they have ideas, that they have something in them they want to fight for, and that they wish for the betterment of their own people.

There, elements and essences that would have given you great privilege mattered less than if you have any intention to think for the good of all life.

The beauty is that the bookstore is the dressing—an excuse—for all kinds of people to have access to it, and experience first-hand the joy of being a thinker.

It was that solitary place at Padre Faura. Had people come in the afternoon during the late 1990s, undoubtedly they would have met Joaquin themselves. If it was another point in time, a layman would have browsed the aisles at the same time that an Egyptian diplomat did.

Because it was not a cocktail event for the privileged or for those who can meet some high-bar set by a committee: It was the call of a humble bookstore.

Unlike others, it lends an air of freethinking. One could, just like Tonet observed, converse with each other without any fear that they are encroaching in someone else’s space. It is not simply a store where one is inclined to shop for books and exits without speaking a word.

It might be the history of the place that gives that atmosphere, because this writer surely had not seen any other that felt like it. Because of such history, a fellow is also drawn to converse with peers, as it encourages thought exchanges.

Here, solidarity was for everyman; it meant the breaking down of barriers.

But now with a change of ownership, a question pervades: Will solidarity still stand up? Could it still remain in the same place as it did when F. Sionil Jose or literary luminaries gravitated toward its hallowed grounds?

Or did it pass away alongside the national artist who kept it thriving?

For what it had become over the years, it is quite funny that F. Sionil’s original plan was just to have his own space.

“When it started, my father just wanted to have an office. He had plans on having a publishing house,” revealed the son.

But the property was too big. The national artist asked his wife Teresita what they should do with the place downstairs. It was she who suggested for the ground area to become a bookstore.

It was the suggestion of a lifetime. Had she opted for a private space for the family, there wouldn’t have been Solidaridad. The ideas and stories it had generated would have seen scatterings, or they might not have never been thought of at all.

One could only hope that such a place would pop up in some street, and that it would attract the same kinds of people that Solidaridad did.