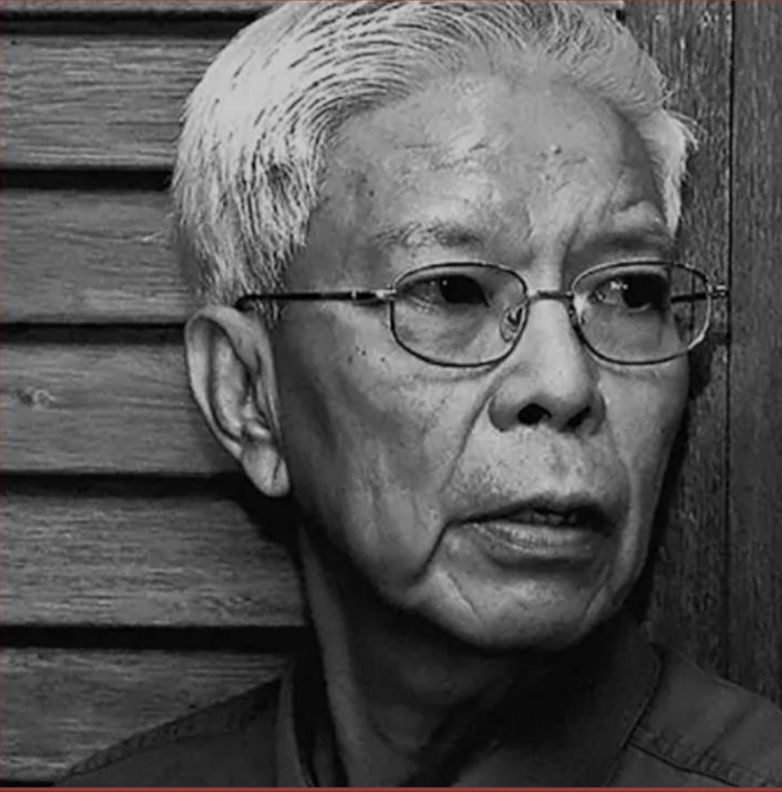

On September 26, the Filipino literary titan, maestro of the Philippine short story, and former Graphic editor Gregorio C. Brillantes passed away at 92. His death leaves another chasm in Philippine literature, which Nick Joaquin and F. Sionil Jose, among others, have already carved out for the past two decades.

And in his absence at this point in time of our country’s history, where the rot of some government officials have been publicly revealed with damning evidence, televised and broadcast for the masses to witness, I am starkly reminded of his first article in the Graphic as its Senior Editor and just how much little had changed in thirty-two years: Corruption in the higher seats of society still sucks the life out of a country that has the means and capability to become great.

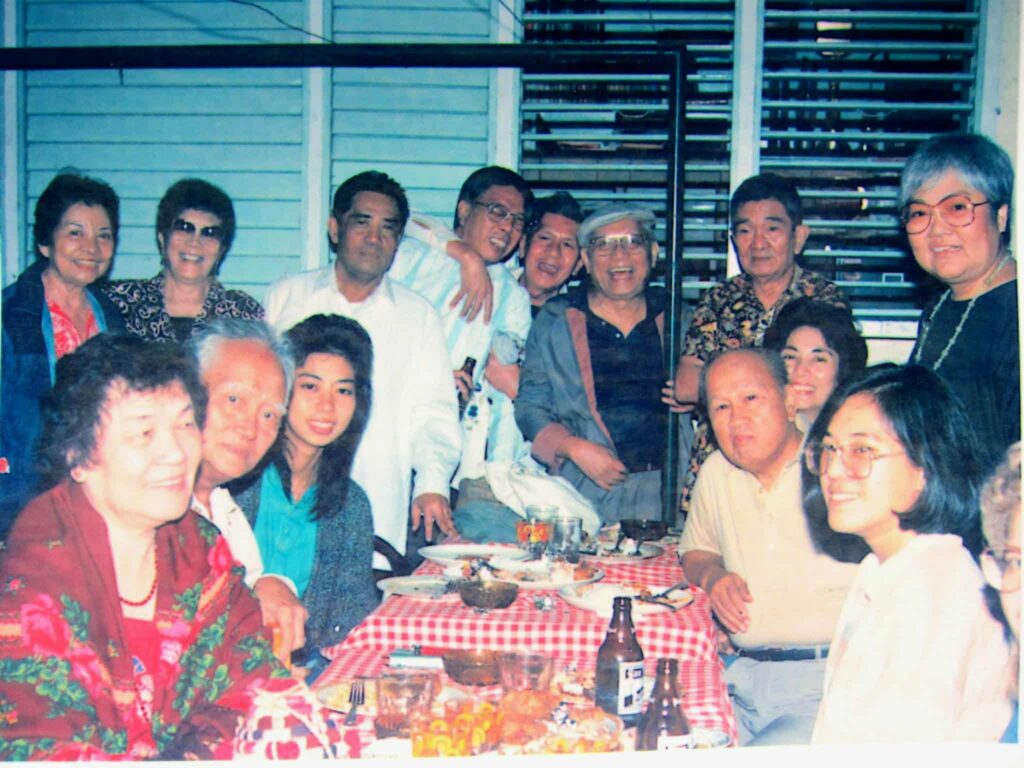

The staff box was packed with heavy hitters in the 1990s, and even more so were its roster of contributors. Many of its staff were either already titans in literature or media, or would become one in the future. The late National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin stood as the publication’s editor-in-chief, Gawad CCP Awardee Jose F. Lacaba as its Editor, and Gregorio C. Brillantes made his first appearance in the Graphic staff box on June 14, 1993, with the title of Senior Editor.

Brillantes’s feature article, The Youngest Hope of A Tribunal On Trial, would first appear in Philippine Graphic almost two months later, on August 13, 1993.

It was a profile on the recently appointed Justice Reynato S. Puno, who was brought up to one of the judiciary’s most sought-after positions, Associate Justice in the Supreme Court, by the late President Fidel V. Ramos. Puno was 53—the youngest to become part of the High Tribunal.

At that time, the Supreme Court was drowning in allegations and impeachment complaints. Former Chief Justice Andres Narvasa and at least three more justices in the House of Representatives received “three new impeachment complaints,” all filed by ordinary Filipino citizens who claimed that the Court was guilty of committing unconstitutional acts and decisions.

It would be an understatement to say that the name, image, and soul of the Supreme Court, the highest of all Courts in the Philippines, was marred. The appointment of Justice Reynato Puno was seen as a move in the right direction. As Gregorio Brillantes wrote, he was “the youngest hope of the tribunal still besieged.”

The Graphic stood as one of the venerable magazines at the time; the thoughts within its pages had weight on how a lot of Filipinos might perceive a certain subject. Though the reputation of the Court ultimately relied on Puno’s performance and the promise of his decorated experience, Brillantes’ long, spectacular feature on Puno, I reckon, contributed to easing the turmoil in the public’s mind, regardless if it was not Brillantes’s intention in the first place.

That said, even if Puno had the most interesting life that a writer could write about, even the greatest story that could possibly exist can only go so far under the pen of an amateur. Fortunately for us—and for Puno—Brillantes is anything but an amateur.

MASTERFUL CONTROL

Considered as one of the greatest short story writers in the Philippines, Gregorio Concepcion Brillantes is light years away from being an average writer. His command of the English language is what any writer could only aspire to achieve. His sentences, even the long ones, cut through the noise of the mind.

What I found striking about his writing was his “entrance.” One could tell a lot about one’s writing through his “entrance.” It could be as short as a sentence, or be as long as a paragraph or two. A reader might find himself lost in the opening paragraphs of his feature, “The Youngest Hope of a Tribunal on Trial.”

He sets so vividly the space between Taft and Padre Faura, along its streets and sidewalks, the inhabitants of the regulars and the passersby, and the commonality (and uniqueness) in their behavior. He wanders, but never aimlessly; in fact, he wanders so specific a route he might have had a compass for an eye.

His writing is exact, precise, and moves with objective. Exact, not in the sense of conciseness for its own sake, but in the sense of masterful control of how a story flows. He gyrates around a place if the matter requires it, he stands still if the prose demands it, but always he would move in accordance to some perfect compass in him that guides him to the next right sentence and the next right paragraph.

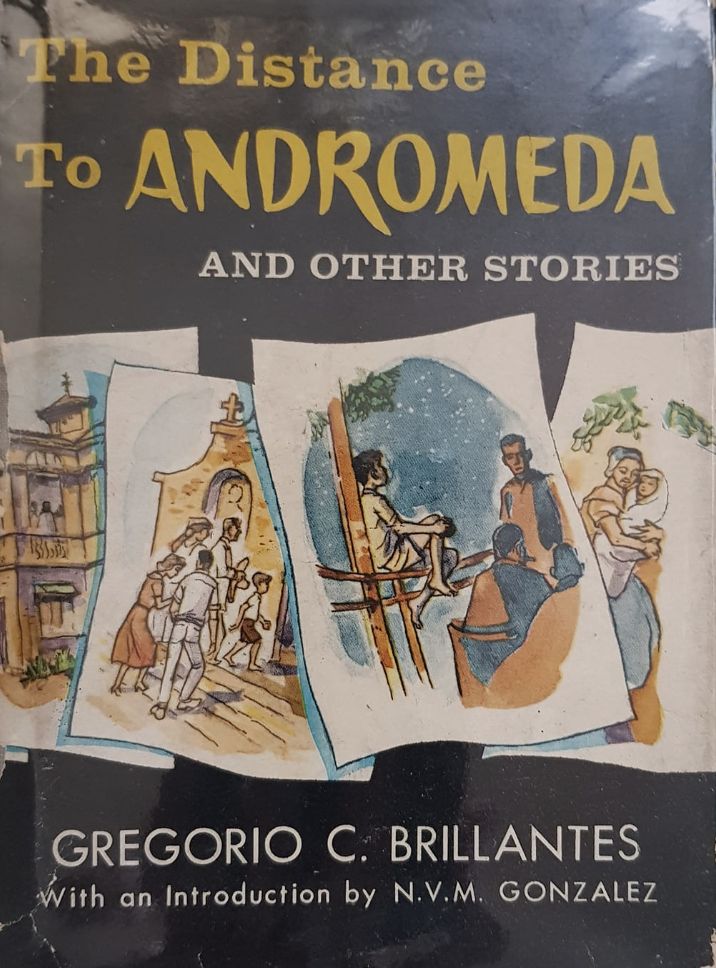

There is wonder, an imagining, a thumping and vigorous beat in his phrasing. It pulls in. So controlled is his pull that he could either concoct a beginning that slowly reels in a reader, or jerks them into action. He begins his famous story, The Distance to Andromeda (1960), like this:

“The boy Ben, thirteen years old, sits tense and wide-eyed before the screen of the theater, in the town in Tarlac. His heart thumps in awe and excitement, and his hands are balled into unconscious fists, as the spaceship burns its blue-flamed journey through the night of the universe that is forever silent with a high metallic hum.”

Or going back to his feature, his entrance was: “It looks like it’s going to be a long haul when you scan the country, or even just this part of town, from the corner of Taft and Padre Faura—a long dazed journey, not to “Philippines 2000,” the splendiferous miracle promised FVR’s faithful a mere seven years from now, but to reality of NIChood probably a century hence.”

And in the succeeding paragraphs, he becomes a cartographer, carefully mapping out corners that have life in every inch, and all those who walked and breathed along its roads would end up reliving a memory they vaguely had.

Whether it was the combination of his magnetic words, the truth in his writing, or the subject matter, the feature he wrote for the Graphic eerily echoes the same hum as the most recent happenings in the Senate.

Corruption had existed for God knows when. And God knows at what exact point in time did the Philippines fall into the quicksand of ill dealings and maligned politicians. At what specific occasion did we lose grip over our country’s soul? Corruption has turned into an “open secret” rather than an obscure, hidden event. It became an expectation rather than a surprise.

Did justice genuinely improve in the past 32 years, or did it simply get a prettier dress? But the same old rot remains at its core like what Brillantes witnessed in 1993 and the decades before that—the highest court in the land dragged down in the trenches, flooded by impurity, drowning the justices in it?

COINCIDENTAL HUMOR

His work had a coincidental humor in it, too. He wrote in his feature article: “Nothing of course in the order of a Bong Revilla or Robin Padilla flick is expected to disturb the solemn tenor of their days. But the justices these days, or so one gathers from that “polluted environment,” are no longer as unperturbed in their remote niches as the people once perceived them to be, ages before the Supreme Court’s present critics began besmirching the august walls.”

Would he believe back then that the two people he mentioned would later on become wrapped in politics themselves and, in so many ways, disturb the solemn tenor of everyone’s days as the public seems to commonly air online?

Coincidence or divine planning, one could see it as a fact that things do eventually change. The manner in which things did change is up for debate, as the political climate right now rarely unites everyone in thought, even in the terrible situations such as the ones we are in right now. But things do change, even if in small ways.

The strain of 1993—tangled up into knots by the events of the years that preceded it—seemed, in Brillantes’s writing, like a scene each generation had a familiar version of.

The good thing about writing, like those that existed in the Graphic, is that they ensnared thoughts of the time. Like a mosquito caught in amber, the joys and frustrations of the epoch had influenced the attitude of Brillantes’s words.

They were daring—the writers. They steeled themselves with great courage and wrote with equally great exactness. I sometimes wondered how it was possible that a league of such high caliber writers congregate into a publication, as it did multiple times for the Graphic? Names such as Ninotchka Rosca, Amadis Ma. Guerrero, and Renato Constantino, among many others, had occupied a space in the staff box.

And it was not only in the editorial box that Graphic found some noteworthy names—its contributors had a long history of publishing stories by writers who would end up becoming an important figure in history, such as Paz Latorena, Jose Garcia Villa, F. Sionil Jose, and Blas F. Ople, just to name a few.

Gregorio Brillantes was a titan who stood among other titans, and they were all so skilled in their own right that they stood under no one’s shadow. His passing on September 26 of this year, however, will undoubtedly cast a dark shadow for some time. Not so long ago, we lost F. Sionil Jose and many other magnificent writers in the time in between, all contributing to a larger and larger shadow over the nest of literature in the Philippines.

For when titans fall to the ground, still summon a long, mountainous shadow in their wake, especially when we, the common people, could only stand beside their rare greatness. Like all other mountains, it is only a matter of time before the sun rises above its summit.

But for now, we could only face the night skies, assume that we’re shooting our eyes right in the direction of Andromeda Galaxy, and hope that the fiery spirit of the magnificent Greg Brillantes is on his way there.