Chinese Immigrants Come to Our Shores, Put Up a Bond to Show Good Faith that They Will Appear When Called, and Then Silently Disappear and Are Swallowed Up by Their Fellow Celestials—Customs Bureau Due for a Shake-up

June 26, 1929 — While from the standpoint of a layman, government bureaus seem to be working smoothly the year around, still auditors detailed to look over records have unearthed grave anomalies that have existed for the past few years and yet kept secret by their directors.

After the bureau of commerce and industry was made “famous” by the Engineer Island scandal with the accused waiting for their respective fates, came the postal bureau before the public eye, with several irregularities being found almost daily by the special investigating committee.

The bureau of customs seems to be the third on the carpet. Already, grave anomalies have been discovered by the customs survey board at an investigation made a few months ago. The alleged findings seem to center around the immigration division—the division responsible for the entry of so many undesirable immigrants to the Philippines.

In a broad outline, the findings of the committee point to a certain Jose Alindogan, alias Yap Bun Wan, a Chinese immigrant agent, who wields an extraordinarily tremendous influence in the bureau. He has been styled the second collector of customs, though outwardly his positions are special agent No. 1 of the collector, baggage contractor, steamship agent, and immigration agent.

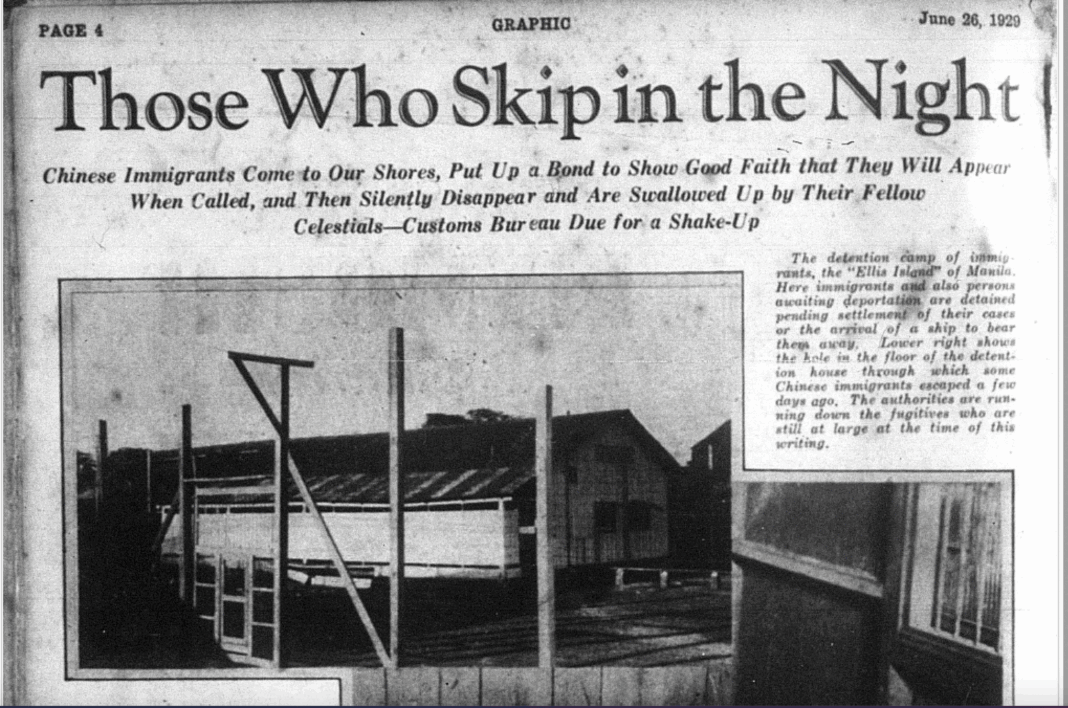

The immigration division takes charge of the registry of approximately 20,000 Chinese in the Philippines every year. It is also responsible for the deportation of undesirable Orientals as declared such by the board of special inquiry after arrival in Manila.

The division may be widely called the intimate “friend” of local downtown brokers who deal with the visitors. They look after the case of the celestials while under probation. They file the necessary bond amounting to P500 per head, and in case of a disappearance of the client, the sum is cheerfully forfeited.

The escape of thirty Chinese recently caused the broker in charge to pay the government approximately P15,000. The arrest of the absconding criminals was also ordered.

Yet, no tears need to be shed for the brokers, for it is alleged they make a fortune out of the escape of their clients.Simple mathematics would show us that any Chinese residing in any part of the country could easily earn an average of one hundred pesos monthly, either by going around buying bottles, or repairing shoes, or owning a ‘sari-sari’ store on a street corner.

Since rejection of an application by the board means a sure deportation to the homeland where livelihood is difficult to obtain, the Chinese would certainly prefer making good his escape and arranging to pay his indebtedness with his bondsmen in liberal terms.

If a Chinese earns say one hundred pesos a month, he would be willing to pay eighty pesos as an installment on his confiscated bond. Any Chinese would do this since he knows pretty sure he could live on the balance of his income without undue hardship.

This article came from the archives of the Graphic magazine, which originally came out on June 26, 1929. The article did not have any byline, thus keeping the author’s identity anonymous.

Read the accompanying “100 Years of Graphic” essay here: