It was my first time, some three years ago, to attend the Manila International Book Festival (MIBF) at the SMX Convention Center in Pasay. I was with a good friend then. Metro Manila still carried the bite of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the restrictions had just barely eased to accommodate large-scale events like the MIBF.

Everyone still had their masks on. Stations for alcohol dispensers stood at the entrances and exits, and almost everyone had an alcohol spray or a hand sanitizer inside their bags, their hands free to pick the books off the shelves.

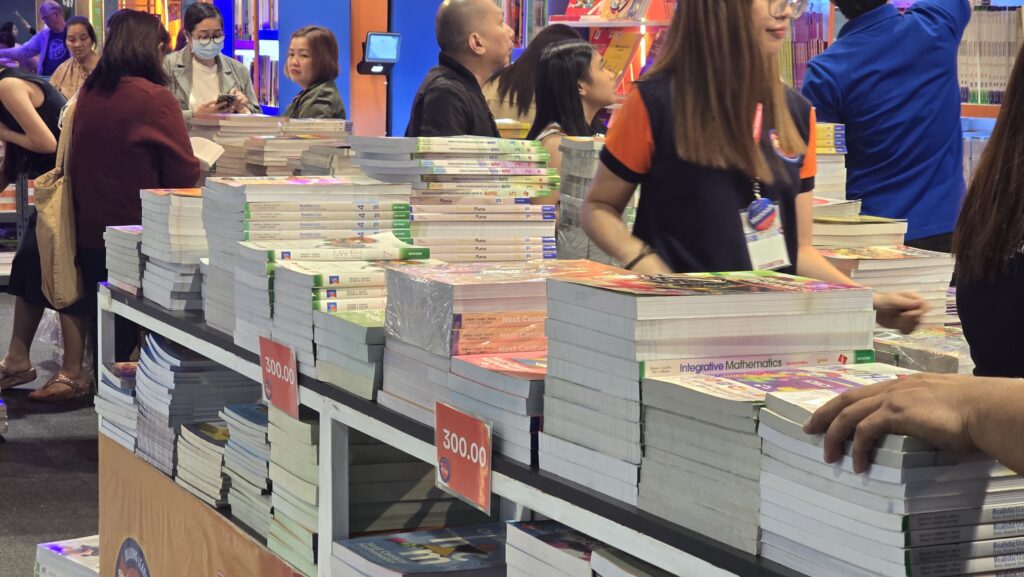

Never have I seen such a huge congregation of people gather at a single venue for the single purpose of stacking up literature to consume. Carts and baskets were filled with books, piled up atop each other, beside one another.

When I visited MIBF this year, thousands upon thousands of people showed up to savor a day of books and eventful meetings. On the MIBF website, they said that the event attracts more than 160,000 annual visitors.

In an article by the Philippine News Agency (PNA) published on Sept. 14, this year’s attendance already reached 120,000 by its fourth day.

If, for a generous estimate, we assume that it had half of that in 1980 when it first started under the name “Bookfair Manila,” and generously apply that in all the succeeding years, the most generous estimate would land us at 3.6 million people. And if we take the current annual estimate, the number would rocket up to 7.2 million people. That works for the 80s and 90s—even up to 2010s.

RISE OF THE INTERNET

The digital age we are in right now has advanced the ease of access to books. All the paperbacks and hard covers ever displayed in the MIBF since it first opened its doors in 1980 could all exist within one’s fingertips, if, say, you’re subscribed to a Kindle or any similar service that offers a digital library.

The rush of the Internet made access to many of these books possible. The rise of book-related services such as Kindle or the boom of online stores like Lazada, Amazon, and Shopee, made it easier than ever to get any book you could realistically think of getting. Even bookstore giants such as Fully Booked and National Bookstore have their own online stores.

Public-access libraries are also plenty, for those who wish to browse or borrow a book without spending a centavo.

In this regard, however, the Philippines showed a steady decline in readership. According to the 2023 National Readership Survey by the National Book Development Board (NBDB), only 42% of respondents read for leisure, compared to 54% in 2012.

CHAMPIONING READING, LITERATURE

To ask “what then is the point of book fairs?” would be misleading. The point had always been to champion reading and literature.

Even if it is for profit, the earnings that the publishing houses would take home each day would help their business to thrive. And if a publishing house thrives, they would reach more readers and authors will get their audience and share of the profit.

To ask why book fairs remain popular is also a moot question. There are already the obvious answers, of course. Sellers at the Manila International Book Fair slash their original price—usually somewhere around 20% to 40% off—which saves a lot for the ordinary buyer.

The physicality of books is also preferred by many, as reported in the previously mentioned PNA article, noting how physical books exercise the senses more than the digital format.

SOCIAL, BUYING EVENTS

A book fair is also a social event, as much as it is a buying event. People with generally the same interests are pulled into the same event, gathering into one place, with hopes of seeing one of their favorite authors or interacting with a fellow bookworm.

The more appropriate question then is: “What do all of these things tell us?”

Let’s strike out the most obvious answer: print is not dead. It’s not going away anytime soon. Print have technically existed since there were papyrus scrolls more than 4000 years ago. Codices—which are closer to the kind of books we are familiar with—existed as early as the 1st century CE.

The physical books we have today could trace its modern origin to the 15th century, upon the invention of the printing press, which made the production of books faster, easier, and more accessible.

Even in the Internet age, physical books did not end up on the chopping block. Neither did e-books drag their physical versions to the guillotine for a permanent beheading.

As long as humans are in want of something real, remain capable of nostalgia and simplicity, and—hopefully—don’t evolve to a featherless biped without the five senses, print will find its way to survive.

EDUCATION & READING

What the popularity of book fairs in the Philippines, existing just alongside the decline in readership, tells us is the need for our government to continue pushing the throttle for literature to remain as an attractive pursuit in the public consciousness.

Education should instill a love for reading for its own sake, not as a rudimentary and lifeless means to a particular end.

Efforts do exist to promote literary interest to the people, but annual fairs or “awareness holidays” that exist only in shallow passing and beautifully designed publication materials posted online won’t cut it anymore.

Even if we remind our fellow citizens on National Literature Month that books exist, or hold a five-day long event to champion local literature, it should never stop at that.

If we are indeed serious in improving reading interest in the Philippines, shouldn’t our education system reflect this? And if we are efficient and effective, shouldn’t there be a rise in readership, not a decline?

As a fresh graduate who went through the entire K to 12 system, my literature degree might be blindsiding me to some other truths on how our country is instilling the spirit of reading to our youth.

But then again, this responsibility of nurturing a reading nation doesn’t solely rest on the shoulders of our educators, but on each of us—our parents, our friends. It rests on our economy, politics, or international factors that influence our way of operating as a society.

Our national hero Jose Rizal is a writer and a scholar, known for inspiring revolution and unity primarily through literature. Yet, it comes as a great irony that there is a growing number of Filipinos today who have not read his novels and other writings.

This year, the MIBF had160,000 annual visitors. And, although this might sound big, it is still miniscule when compared to the country’s total reading population.

In the National Capital Region alone, the total reading population in 2024 is around 14 million, which means only around 1.14% of the country’s total population was in equivalent attendance at MIBF.

Take our country’s entire population—which President Bongbong Marcos declared in July 2024 to be 112.7 million—and it makes those in attendance of the MIBF only 0.14% of the entire population.

Granted, the MIBF is only one of the many book fairs happening around our country, but this puts into light one thing: We still have a long way to go in becoming a reading nation. We still have a lot to do to make it happen, but book fairs and general celebrations of literature are a good start.