Juan Luna’s ‘Hymen, oh Hyménée!’ drowns the public with overwhelming passion for the last time, 132 years later.

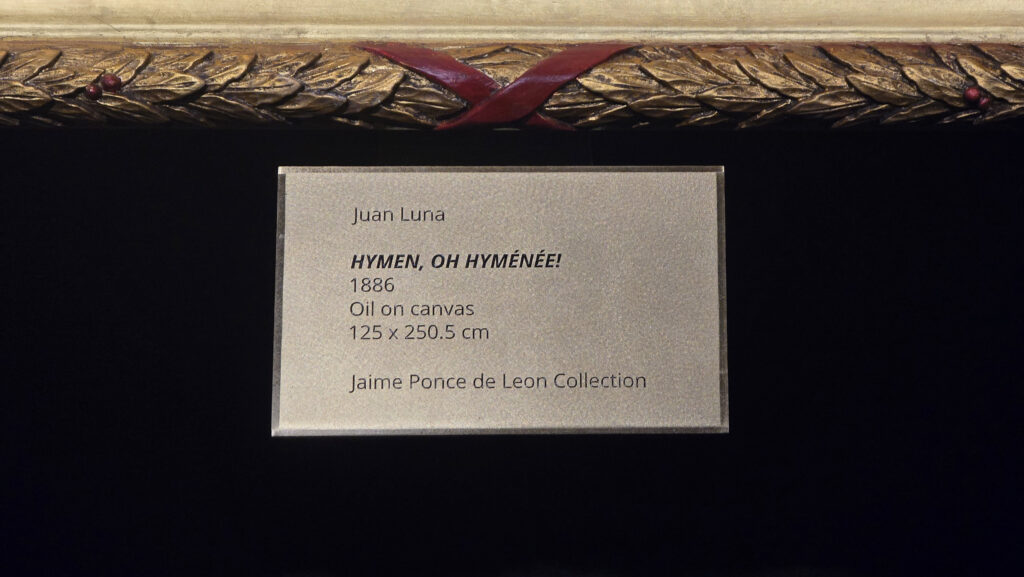

From Oct. 7 to Oct. 16, the Ayala Museum held a special one-object exhibit. It was for a painting dubbed as “the holy grail of Philippine art.”

The space where it was situated at the Ayala Museum in Makati is perhaps the most fitting respect given to an artwork: dark, silent, and spacious enough for a small crowd, with a lone recamier fixed right in front of a single painting. A row of small lights hangs from above, directed at the painting and set with distance from it, thus reducing the ugly and distracting glare I often criticized in many museums. Unobtrusive, velvet rope stanchions gave the painting space to breathe, stopping spectators from coming too close to it.

I stopped and absorbed what was before me so as not to forget it. Because in less than 30 hours, Juan Luna’s Hymen, oh Hyménée! will bow out of public view and become part again of a private collection.

Akin to a suspense drama or a Dan Brown novel, the story of ‘Hymen, oh Hyménée!’ is entrenched in intrigue, conspiracies, politics, love, and an aristocratic family.

‘Hymen, oh Hyménée!’ got its title from a nuptial chant written by the ancient Roman poet Catullus, invoking the Roman god of marriage Hymenaeus for a flourishing union:

Now is it time to rise, now to leave the rich tables;

now will come the bride, now will the Hymen-song be sung.

Hymen, O Hymenaeus, Hymen, be present, O Hymenaeus!

Luna, the master painter, often drew inspiration from ancient Roman culture. This is evident in many of his works like the Spoliarium or his 1882 work Las Danas Romanas (The Roman Dames).

His appreciation of Roman art stemmed from his visits to Rome with his professor, Alejo Vera, whom he developed a close friendship with upon enrolling at the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid.

VENERATION FOR ROMAN CULTURE

For the rest of Luna’s career, his admiration for Roman culture and antiquity would manifest in his works. This veneration is sharply displayed in Hymen, oh Hyménée!

Also called “Boda Romana” (Roman Wedding), Luna depicts the titular scene of an ancient Roman tradition where the bride and those accompanying her sing to Hymenaeus, as the bride is escorted away to the bridegroom’s chamber.

The painting measuring 125 x 250.5 cm (or 1.25 x 2.505 meters) is small compared to Luna’s other masterpieces, such as his 1881 painting The Death of Cleopatra (250 x 340 cm) or his gigantic 1884oil painting Spoliarium, which measures at 4.22 x 7.675 meters (422 x 767.5 cm).

And yet its size managed to dominate the room it was displayed in, perhaps just as well as the Spoliarium did at the National Museum of Fine Arts.

Juan Luna and his masterful use of perspective managed to turn the painting’s gilded frame into a portal—as if the atrium in which the ceremony was being held was simply in the next room, a tiny bit beyond the reach of the spectator.

Such display of one’s skill is expected from a master of the craft who painted it at the height of his fame and creative excellence.

Plenty had already been said about Hymen, oh Hyménée! with regard to its content and context, and even more so for its painter.

Set in the atrium of an affluent owner’s private residence, the ceremony features a host of characters, but nowhere is the bridegroom physically present. The only presence that could be attributed to him is the space which the figures occupy. It resembles that of a domus—the kind of residence that noblemen and wealthy residents of ancient Rome own. An ornamented wedding couch, marble floors, hanging oil lamps, majestic frescoes, towering doric columns—the bridegroom’s presence literally surrounds the cast.

It is a lavish party. Flowers of all kinds and colors are scattered on the floor. Performers, servants, spectators, a legionnaire, and 10 bridesmaids merrily send the bride to the chamber as the mother, dressed in black and red, accompanies her and three boys lead the way.

Closer look at the characters of the painting

The right side is dominated by vitality and activity—visually marked by the generous amount of Pompeian red that divides the space—as the direction of the painting leads toward the left, where the scene seems to slow down and brighten up.

Everyone is caught in candid form. Preliminary sketches of Luna showed him studying and posing the characters in the middle of the action, then later assembling them onto the scene.

MARRIAGE & THE BRIDE

By the time Luna started working on ‘Hymen, oh Hyménée!’ in 1886,he had already garnered international attention for his colossal obra maestra, the Spoliarium, which won a gold medal at the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes in Madrid two years prior.

It was also the same year when he met Paz Pardo de Tavera, the daughter of a well-respected family, and a descendant of Spain’s Grand Inquisitor.

He was by all means madly in love with Paz. However, due to their differences, Paz’s mother, Doña Juliana, initially disapproved of their relationship.

Luna was close with Paz’s brothers, Felix and Trinidad, who convinced their mother to think through her prejudices and see Luna as a fitting man for Paz. Eventually, their mother relented.

After marrying Paz Pardo de Tavera, the two went for a honeymoon through Rome and Venice where, in a streak of golden inspiration, Juan Luna began painting a series of artworks, one of which would end up being Hymen, oh Hyménée! about a year later.

One might naturally assume that the scene is a depiction of Luna’s own sentiments about his own relationship and how he viewed Paz. The absence of the husband cripples the audience’s ability to know what Luna thinks of him, and therefore, we lose a way to know if this was indeed his rendering of his own marriage.

All that we know of the husband is his potential wealth and status. Remember that Paz is the direct descendant of Juan Pardo de Tavera, former Grand Inquisitor of Spain and Archbishop of Toledo. At the same time, remember that Luna was a Filipino from the northern part of Luzon during Spain’s reign in the Philippines.

If we are to assume that the bride is Paz and that the husband is Luna, then the painter must think of himself as having gained immense status after being married into an illustrious family.

The bride, meanwhile, appears ghostly and ethereal in all white. There’s softness in her deportment. The image is further contrasted by her mother exuding sternness and confidence. She seems to be carried away, likely toward submission to her husband, as suggested by the turtle near the bottom of the painting—backed into a corner, trapped in a place of no return, moving toward the right, opposite to the direction of the scene’s action.

Starting from the right—which exudes verve and vibrancy—and moving to the left—where the scene is quieter, one could see it as moving away from vitality and freedom, and towards simplicity, silence, and perhaps, if one is too pessimistic, subjugation.

I noticed that out of all the characters in Hymen, oh Hyménée!, only the bride dressed in a veil seems to look back over her shoulder. She, too, is in the middle of turning her head. Even the child on the far left, who at first glance appears to look back, does not glance over his shoulder. The young boy’s body faces us—the spectators—as he glances to his left.

If we think of looking back as an action of desiring pieces of the past, only two characters seem to show it—the bride and the turtle.

The only difference is that the turtle is in active pursuit of it—moving to the right (the past)—but ultimately ends up stuck and unseen.

As for the bride, from what I can surmise from the look in her eyes, she seems to convey a particular form of looking back—that of bittersweetness and hesitance, and ultimately an acceptance of one’s fate, like that of the turtle.

The boldness, brightness, and vigor of Hymen, oh Hyménée! is also underlined by longing, hesitance, and an iota of powerlessness. If we take the faces of her retinue as a basis for happiness, she does not seem to exude the same attitude as they do.

LOVE & INSANE PASSION

Can we truly say for certain that the bride is absolutely happy about the idea of being married?

Luna entered the artwork in the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, where it won the bronze medal, and skyrocketed Luna to even greater heights. The piece stayed in his studio and became one of Luna’s personal favorites.

I would say that the painting foretold of Luna’s overwhelming passion—and the peril that came with such passion.

The entrance to the one-object exhibit skews to the left of the painting—specifically, to the southwest—so upon entering, the visitor is greeted by a foreshortened beauty, and immediately, the eyes are drawn to the powerful vibrance of Pompeian red and briefly to the plethora of characters near it. Then to the mother, who bears another hue of red, who stood beside the ghostly figure of the bride, where my eyes ultimately rested on, as if a respite from the overpowering energy of the painting.

When I sat there at its second to the last day exhibit, it was not only awe which struck my heart, but passion, as well. And when I sat at the lone recamier fixed in the middle of the room, I swear that I could feel myself drowning. I was alone for a while, and there was no one else for the painting to share its passion with other than me, who was already left paralyzed by its beauty.

I wonder what passion from Luna it was that I felt. Was it the passion for the love of the arts that Juan Luna would undoubtedly have—the creative high of a man at the zenith of his fame and skills?

If the painting was indeed his creative interpretation of his love and his marriage to Paz, then one could see it as the highest form of appreciation that Luna was perhaps able to conjure. It was, after all, a depiction of a Roman wedding from classical times, where beauty, love, and the divine swathe the artistic expressions of many other artists influenced by Classical themes.

Was it the passion of being madly in love, or only of madness that lurked deep in his psyche, unbeknownst to him would end up manifesting as crime of passion?

Or was it that form of passion—crime of passion—one from the blinding rage, jealousy, and paranoia that drove Luna to take a gun and kill the subject of his affection and obsession on September 22, 1892?

To know what Luna thinks of love and passion, one only needs to look at this painting. It reeks of a man looking at love through rose-colored lenses. Whether this view changed along the course of his marriage to the point that he murdered his wife and mother-in-law, that we can no longer verify.

“My trial will probably be held toward the middle of next January and despite my sad situation, I almost prefer to wait resigned and patient this New Year because I can assure you that this has been a disastrous year for me I am looking forward to see it disappear off the calendar,” Luna wrote in a letter to Don Ezequiel Ordoñez, a lawyer and a notable political figure, while he was in prison.

The French court later acquitted Luna of this crime on February 8, 1893, and labeled it under crime passionnel, temporary insanity caused by passion.

Acquitted or not, it does not take away the fact that one of the most prominent figures during the Philippines’ fight for independence had killed his wife and shot his mother-in-law in the head.

MYTHIC STATUS, SPANISH HAND

When Juan Luna died in Hong Kong on December 7, 1899, the painting disappeared. There were some rumors of its presence in the years to come, as much as there were stories about how it even vanished in the first place.

In the years of its absence, Hymen, oh Hyménée! developed a mythic status, like that of King Arthur’s sword Excalibur or perhaps Christianity’s Holy Grail or the Ark of the Covenant. The only difference is the veracity of its existence, as Juan Luna’s painting stands in the realm of hard facts.

Traces of Hymen, oh Hyménée! were only seen in records, in the background of old black-and-white photos, or in sketches that Luna had done in the course of making it. Other evidence of the painting came as approximations of the real thing, turned into hand-colored lithographs, but the authentic item was nowhere to be found.

The art world dubbed the painting “the Holy Grail of Philippine art.” It had been missing for more than a hundred years, entangled in the controversial life and love of the master painter.

There were theories as to what had happened to it. Some said that the family of Paz Pardo de Tavera had it burned, alongside Luna’s other paintings. Others thought that it had become a victim of war—destroyed or plundered—and robbed the world of an obra maestra, like many wars in history had done.

Hymen, oh Hyménée! Juan Luna’s Long-Lost Masterpiece is a documentary directed by Martin Arnaldo. It was created in partnership with the Ayala Museum and traces the discovery and recovery of Juan Luna’s painting of the same name. The documentary indicated that Filipino artists and their works suffered after the Philippines gained its independence.

What was seen as progress for the Filipino people, Spain deemed as betrayal. Soon, Spain sought to systematically erase whatever contribution the Filipinos have made to its art and culture.

Carlos Navarra, the in-house curator at the Prado Museum in Madrid, said that during the years that followed Philippines’ independence from Spain in 1898, there came “a policy of absolute silence about Filipino artists,” treated to what would amount to as putting a curse of “invisibility” to Philippine artistry. Existing artworks were deposited to various institutions, hidden away and collecting dust for many years to come.

At one point in history, Luna’s ‘Hymen, oh Hyménée!’ must have suffered the same fate as well.

MONUMENTAL DISCOVERY

Rumor had it that the long-lost painting was in the private collection of a European aristocratic family. The late Dr. Eleuterio “Teyet” Pascual, one of Philippines’ foremost art collectors, had seen it before when he attended a party at the house of a noble in the 1970s. Teyet tried to acquire it, but to no avail. The family was not willing to sell.

He told this monumental discovery to Jaime Ponce de Leon—a famed art collector, auctioneer, and owner of the acclaimed León Gallery in Makati—but Teyet did not name the family, a secret he took to his grave when he died in 2012.

Though there was not much to go on, it confirmed the painting’s existence. It took a long time of patient investigation and calling up all potential noble families in Europe. Then Jaime de Leon finally got a call one day for a visitation at the house of an old friend—a member of an aristocratic family.

He did not know what to expect. All he knew was to come by at around 10 in the morning. Inside the house, there were many paintings on display like that of a Monet—but no Luna. After the pleasantries, the man of the house produced the painting. Hiding behind dark velvet curtains, the long-lost Luna masterpiece revealed itself once more to a Filipino.

And in 2014, the family was finally willing to sell it, thus landing in Jaime’s hands.

It was far from being cheap, but it was worth it. In the 20-minute documentary, Jaime quoted the British figure Lord Joseph Duveen, considered to be one of the most influential art dealers of all time, who said: “When you pay high for the priceless, you’re getting it cheap.”

For what price could ever be too high for something that holds so crucial a piece of a country’s history? Such a masterful work of passion and beauty, ‘Hymen, oh Hyménée!’ could make even an apartment worth more than a mansion.

The painting remained in a crate for three years following an extensive authentication process, and in 2017, ‘Hymen, oh Hyménée!’ reunited with its motherland.

It was displayed as the central piece of Ayala Museum’s exhibit Splendor: Juan Luna, Painter as Hero in 2023, in celebration of the 125th anniversary of Philippine independence. Before that, the last time it was ever seen in public was in the famous Paris Exposition in 1889.

Gino Gonzales, the exhibit’s designer, took cues from classical French architecture and structured it as an enfilade—a style common during the Baroque period featuring a series of rooms, with one leading to the next via doorways symmetrically aligned with each other.

But with what I learned of how the 2023 Splendor exhibit was executed, I say it with great confidence that for such a revered, long-lost masterpiece, the most appropriate treatment for Hymen, oh Hyménée! is that of a one-object exhibit—something of which I had the privilege to experience during its last few days on display.

As I sat there admiring the painting, I came to the conclusion that Juan Luna’s most emotionally moving work is not the Spoliarium. An unpopular opinion, I might say, but having seen the Spoliarium in many visits to the National Museum of Fine Arts, I stand my ground.

Indeed, Spoliarium is the most culturally significant out of all his works, particularly its role in our history and in defining the Filipino consciousness and our battle for independence. Though Luna himself is not open about the political engine and social critique powering Spoliarium, his friend Jose Rizal nonetheless saw the painting in that way.

As Rizal said in his speech at a banquet in honor of Juan Luna and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo in Madrid, 1884, “the cry of slaves, the metallic rattle of the armor on the corpses, the sobs of orphans, the hum of prayers” is heard “with as much force and realism as is heard the crash of the thunder amid the roar of the cataracts, or the fearful and frightful rumble of the earthquake.”

Spoliarium is perhaps his most astounding achievement as an artist, and one of the most technically impressive displays of a master of his craft.

But I surmised that it is not the most emotionally moving. Despite the size of Hymen, oh Hyménée!, its power is comparable to the gigantic Spoliarium.

Perhaps it was also the way that the Spoliarium is presented—bright lights at poor angles that ruins the look of the painting, a distracting large-sized crowd, with many fine pieces of painting around, alongside the fact that I have seen it a couple of times and could see it many more times—I felt robbed of experiencing its entire power and the specialness of seeing it. A quarter of its emotional pull in me is taken away.

This is not to say that it is not powerful or that it did not move me. Far from the truth, actually. But having seen Luna’s missing masterpiece Hymen, oh Hyménée! alone and in silence just delivers a different kind of emotional gut punch.

As a special one-object exhibit, it led me to believe that perhaps the best and only way to experience such a long-lost masterpiece painting is for it to be alone in a room. No other object to distract you from anything. No light to steal the attention, all focus gravitating toward one thing.

The painting becomes the entirety of that experience. Not as one of many stops at one’s course through the museum, but rather a singular and dedicated respect. By doing so, it becomes not a field trip, but a meditation through and with art.

Imagine making a monumental discovery of an important piece of cultural history as that of a lost relic, only for the audience to admire it for a couple of minutes before going into the next.

The audience’s experience of that object becomes a component of the visit, diluting whatever unadulterated awe like those the people at the Paris Exposition would have had upon seeing for the first time such a magnificent painting.

When one is led to the final product after a series of rooms building up the history and process that went into making it, the audience becomes a scholar first, seeing the painting as a collection of references and details that the previous rooms had already untangled for the viewer.

And in the process, all that powerful emotion contained in the painting (and which the painting encourages in the viewer) subtly struggles with the intellectualization of the piece, competing for attention, and ultimately diluting the first-time unadulterated viewing.

Hymen, oh Hyménée! should not permanently stay in any exhibit. Part of its allure is that it had been gone for a long time. For it to keep it the power and intrigue it holds, it must periodically appear to the public once in a while.

Its mythic-like status as the ‘holy grail of Philippine art’ that was lost for more than a hundred years lent an extra blanket of awe upon its reveal.

As I have said, I count myself fortunate that my first viewing of a masterpiece thought to have been lost in the annals of history was barely tainted.

Before seeing it, I knew only six things: the painting’s title, who painted it, what museum it was in, that it had been missing for more than a century, the fact that it was the painting’s last days in public viewing, and that Luna killed his wife and mother-in-law.

I made it a point to know little about it before seeing it—and frankly, those six things are the only things that I needed to know before seeing it. I wish to be astounded purely by its raw power and beauty. I will have plenty of time to know things about it after seeing it.

Had I not known that Luna murdered the love of his life, would I have felt the painting only as an unadulterated passion which comes from the labor of love?

If lunacy is defined as extreme foolishness, then is not love, to some degree, a willful submission to insanity? For a degree of foolishness is required to love. It is the paradox of humanness—that we should all find love equally reasonable and irrational.

The ghost of Luna’s passion continues to haunt the painting. And now, as it goes back to private collection for an indefinite amount of time, knowing I can no longer access it whenever I want, that haunting will stay with me for a long time.

The beauty, the fervor of Luna’s scene and the brilliance in his lush strokes, the look on the bride’s eyes, the chant I imagine the bridesmaids making to the god Hymenaeus as they send her away—all of it will haunt me. I will have to make sure of it.