Understanding the environmental awareness disconnect among Pinoys

The astronauts got it right the first time. It was 1971 and Apollo 14 Lunar Module Pilot Edgar Mitchell peered through the small window of their spacecraft and saw a 360-degree panoramic view of the Earth, Moon, Sun, and the stars.”

It was a profound, life-altering experience of unity and interconnectedness, the then 40-year-old, Texan said.

Interviewed by People Magazine in 1974, Mitchell recalled: “You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there, on the moon, international politics looks so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, ‘Look at that, you S.O.B.’”

What Mitchell and other lunar astronauts experienced has been christened by author, educator, and space philosopher Frank White as the “overview effect”— a cognitive shift stemming from the realization that “the Earth is one system, and we’re all part of that system.”

From orbit, White explained, divisions fade, leading to the idea that “we have to start acting as one species with one destiny.”

Inside Apollo 8 in 1968, Mission Photographer Bill Anders took a shot of a barren moonscape in the foreground and the Earth rising above the lunar horizon.

He dubbed the iconic photo, Earthrise. As reported by The Guardian, the Anders picture would later become “a driving force of the environment movement” in the United States, “showing the earth as a singular, fragile, oasis.”

Michael Collins, Command Module Pilot of Apollo 11, said in a JFK Library Foundation interview that what struck him was the fragility of the earth. “The little thing seemed fragile. And when you analyze the conditions here on Earth, it is indeed fragile. So, the more that we can do to help the planet stay whole and to beef up some areas of its fragility, that’s what we should be spending our time doing.”

In 2003, Earthrise was cited in Life Magazine’s “100 Photographs that Shaped the World.” It was “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken,” said noted Nature photographer Galen Rowell.

FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION

The 1960s saw the rise of the global environment movement fueled by highly publicized ecological debacles, the rising tide of public activism, and the publication of international bestsellers that called for environmental action on a host of issues.

Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking 1962 book, Silent Spring, exposed the indiscriminate use of pesticides like DDT. It served as the environment movement’s primary trigger and led to the nationwide ban on DDT for agricultural use in the U.S. in 1972.

Silent Spring definitively altered the relationship between society, industry, and the environment. It concretely denoted the critical relationship between sustainability efforts and public health policies. This led many citizens, particularly women in local communities, to become active environmentalists.

Moment in the Sun by Robert Rienow and Leona Rienow (1967) critiques American consumerism and resource waste. It helped expand the movement’s focus—from pollution and specific chemicals to lifestyle choices and overconsumption.

Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968) heightened public concern about overpopulation and resource depletion.

SHIFT IN FOCUS

Prior to the 1960s, discussions on the environment was significantly limited in scope. Concerns primarily focused on conservation and public health issues within specific localities, rather than a holistic understanding of ecosystem vulnerability and global environmental crises.

According to the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), “before the 1960s, there was little environmental awareness and only a few isolated international environmental regulatory initiatives.”

Then in 1972, there was the Stockholm Declaration, the first international document to recognize the right to a healthy environment.

A product of the first United Nation’s Conference on the Human Environment, the Stockholm Declaration contained 26 principles that broadly address the interconnectedness of human rights, environmental protection, and economic development.

With the advent of the 70s, environmentalists shifted from just documenting nature’s relationships to one that actively studied how human activities disrupt ecosystems such as pollution, pesticide effects, and resource depletion.

Ecologists began focusing on the moral obligation to protect the environment for future generations (intergenerational equity) moving beyond purely scientific observation.

PUBLIC AWARENESS OVER DISASTERS

Growing public awareness of environmental degradation propelled man-made disasters to the center of public discourse.

Torrey Canyon Oil Spill

The world’s first major oil spill from a tanker occurred off the coast of Cornwall in England after the supertanker Torrey Canyon spilled 119,000 tons of crude oil.

The oil slick affected both British and French coastlines in 1967. The use of harmful detergents to clean up the spill caused more long-term damage to the marine environment.

The Torrey Canyon oil spill triggered significant public outrage and mobilization, which included street protests, artistic actions, and a massive volunteer clean-up effort. The incident is considered a pivotal moment that helped spark the modern environmental movement in Britain and Europe.

Minamata Disease

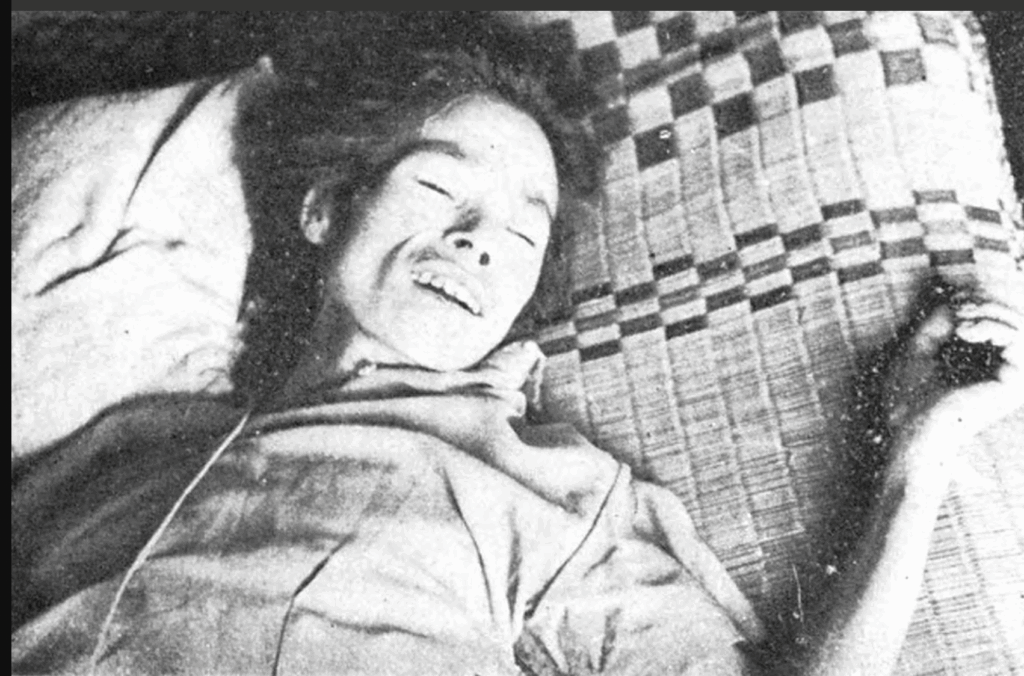

In 1968, more than a thousand people died, and over 30,000 more suffered from Minamata disease, a severe case of mercury poisoning resulting from mercury flushed for decades by a private corporation in Minamata Bay, Japan.

Support groups, such as the Citizens’ Council for Minamata Disease Countermeasures (established 1968), organized and confronted corporate and government authorities.

Photographic essays by W. Eugene Smith, a dramatic photo of a patient (“Tomoko and Mother in the Bath”), and books like Michiko Ishimure’s Pure Land, Poisoned Sea brought national and global attention to the tragedy.

In 1972, two Minamata disease patients were present at the first global environmental conference in Stockholm, shocking scientists, politicians, and the public worldwide with their visible symptoms of mercury poisoning.

Ultimately, the persistent activism, public outrage, and legal battles were central to pushing the Japanese government to eventually acknowledge the cause of the disease in 1968 and pass some of the world’s most stringent environmental laws in the “Pollution Diet” of 1970.

Sta. Barbara Oil Spill

In 1969, a major oil well blew off the coast of Sta. Barbara, California. Millions of gallons of crude oil spilled, coating miles of beaches, leading to the deaths of thousands of birds and marine mammals.

National outrage and coordinated protests followed after widespread media coverage showed the oiled wildlife and oil-blackened coastline of Sta. Barbara.

The 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill protests are often credited with launching the modern American environmental movement.

Environmental activist Selma Rubin described the incident as “the oil spill heard round the world.”

In sum, the sustained protest against the oil spill in Sta.Barbara became a direct catalyst for significant, landmark US environmental legislation. Public outrage and media coverage surrounding the disaster effectively pressured politicians to pass key legislative and regulatory outcomes.

These included: the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, the “Magna Carta” of federal environmental laws; the Environmental Protection Agency or EPA of 1970; Water Quality Improvement Act of 1970; California Environmental Quality Act of 1970; Clean Water Act of 1970, and other key laws such as the Marine Mammal Protection Act (1972), the Coastal Zone Management Act (1972), and the Endangered Species Act (1973).

PHILIPPINE EXPERIENCE

The earliest forms of environmental legislation were enacted during the Spanish colonial period. It began with the Spanish Law of Waters in 1866 (implemented in 1871).

The 1866 law was a key legal framework for water rights in the Philippines. It established that certain waters were public and that others could be privately owned.

It was applied in the Philippines starting in 1871 and recognized both the state’s ownership of public domain waters and the private rights of riparian landowners.

The law governed issues like public land ownership for reclaimed areas, which became private property only after the government declared them no longer needed for public use.

The modern concept of Environmental Awareness and Protection peaked in the Philippines in the 70s, when the government began establishing key legal frameworks.

Early environmental education initiatives started in 1977, with formal recognition and integration occurring through the National Environmental Awareness and Education Act of 2008 (Republic Act No. 9512).

This landmark law established November as National Environmental Awareness Month and made environmental education a formal part of the curriculum in schools and other institutions.

In 1977, the Philippine Environmental Policy was declared through Presidential Decree No. 1151. It became the policy of the government to require environmental impact assessments for projects and to set national environmental goals.

The Department of Education also began integrating environmental education subjects into the school curriculum at all levels.

By 1978, the Philippine Environmental Impact Statement System was established via Presidential Decree No. 1586. Its task was to assess the environment impact of critical projects.

The concept of environmental awareness in the Philippines has evolved significantly over time, with formal efforts at a national level first emerging around the 1970s and 1980s, and culminating in structured national education policies in the late 2000s.

An early initiative included the 1977 Environmental Education, with organizations like the Environmental Education Network of the Philippines (EENP) being established in 1986.

The 1980s saw the rise of local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and grassroots movements that drove early awareness environmental campaigns and advocacy.

The Environmental Education Network of the Philippines (EENP) was established in 1986.

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) was formed in 1987, formalizing the government’s commitment to environmental governance and conservation.

The 2008 National Environmental Awareness and Education Act (RA 9512) is regarded as a legislative milestone and a key turning point, legally promoting environmental awareness through education.

Formal integration mandates the inclusion of environmental education into the curricula of public and private schools and the National Service Training Program.

The government has designated the month of November as National Environmental Awareness Month to increase public awareness and encourage environmental conservation.

ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES

Despite the preponderance of environmental laws in the country, violent clashes have been evident over the years between government forces and those from marginalized groups, such as indigenous peoples and farmers.

These points of conflict have primarily centered on resource extraction projects involving mining and dams, as well as land development that threaten ancestral domains and traditional livelihoods.

In the early 70s, the Philippine government, under the late strongman, Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos, planned to construct four mega-dams along the Chico River in the Cordillera region of Luzon.

To be funded by the World Bank, the four dams, once erected, was touted to generate some 1,010 megawatts of electricity for Luzon, following the global oil crisis of 1973.

A 1980 academic paper titled, “The Chico River Basin Development Project: A Case Study in National Development Policy” projected, however, that the construction of the dams would completely submerge a total area of approximately 1,400 square kilometers of traditional highland villages and ancestral domains.

The paper—presented by Joanna K. Cariño at the Third Annual Conference of the Anthropological Association of the Philippines in Manila from April 22-27, 1980—added that the submerged areas will include 16 Igorot villages, 100,000 Kalinga and Bontoc people, 1,200-2,000 hectares of stone-walled rice terraces, orchards, coffee plantations, 2,500 hectares of orchards and coffee plantations, and burial grounds.

For its part, the Kalinga provincial government estimated that over P69 million worth of farmlands would be lost in Kalinga province alone.

Resistance was the response of the Kalinga and Bontoc indigenous tribes to the planned construction of the four dams.

The Chico River area was militarized 44th Army Infantry Battalion. Despite the military threats, Macliing Dulag and the other pangat (leaders) remained steadfast and would not leave the land.

In the months before his death, 2,000 Kalinga and Bontoc tribesmen held one of the largest bodong (peace council) assemblies. They reaffirmed their unity and officially designated Macliing Dulag ads their primary spokesperson to the outside world.

On the evening of April 24, 1980, military personnel arrived in Bugnay looking for Macliing Dulag and another opposition leader, Pedro Dungoc Sr. When Dulag refused to come out of his home, soldiers from the 44th Infantry Division under Lt. Leodegario Adalem sprayed his hut with bullets, killing him instantly.

In the aftermath of the murder, the Marcos government denied direct responsibility for the killing, but later, facing significant national and international pressure, it took some action by bringing the perpetrators to a military trial.

Then Ministry of National Defense, under the late Juan Ponce Enrile, informed Amnesty International in 1981 that they recommended charges to the men accused of killing the tribal leader. Eventually, an army lieutenant (Leodegario Adalem) and a sergeant were tried before a military tribunal and found guilty of murder and frustrated murder.

With the death of Macliing Dulag, the World Bank withdrew its support for the project and government discontinued the building of the dams.

BIODIVERSE

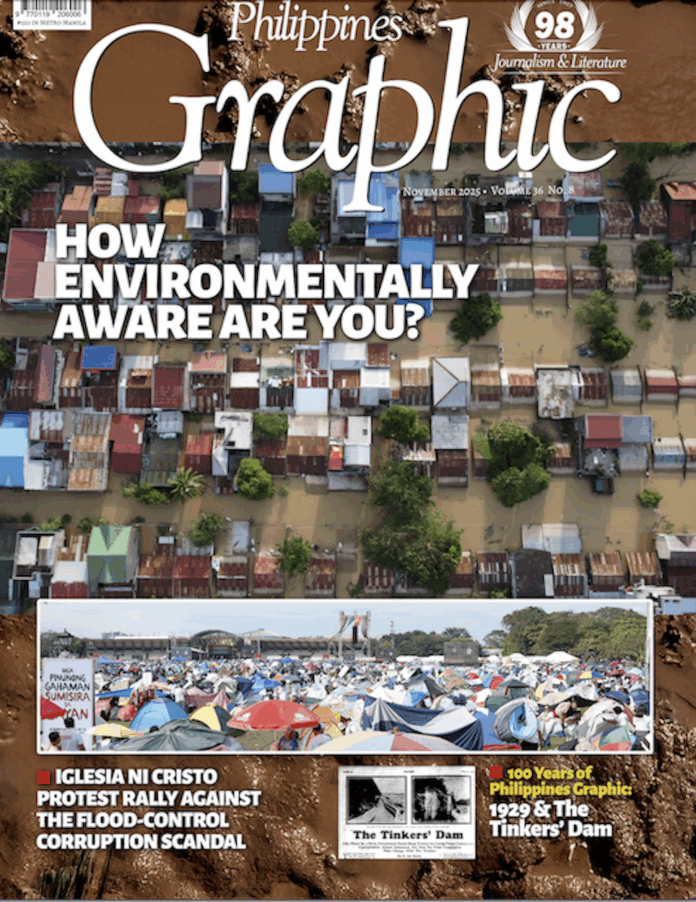

When Filipinos speak of environmental awareness, they usually equate it with climate change and its many adverse effects—typhoons, flooding, drought, intense heat, non-stop rain, and earthquakes.

A knowledge gap exists among Filipinos regarding the nation’s many beautiful and exciting features as a result of its “megadiverse” status.

As early as 1997, a paper presented by the ASEAN Regional Center for Biodiversity Conservation (ARBC) highlighted that “most Filipinos are unaware” of the country’s unique and rich biodiversity, including the urgency for its conservation.

The updated Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (PBSAP) 2024-2040 emphasizes enhancing public awareness as one of its nine priority strategies, implicitly acknowledging that biodiversity awareness needs improvement.

The Philippines is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. Officially recognized as one of the 18 “megadiverse” nations, the country is unique because it has an extraordinary concentration of species found nowhere else on Earth

Over 52,000 described species have been recorded, and more than half of these are endemic to the country.

Davao del Sur, South Cotabato, and in Zamboanga

Spread over the nation’s 7,641 islands, are 70% and 80% of the world’s plant and animal species.

The Philippines ranks fifth in the number of plant species and maintains 5% of the world’s flora.

Jade Vine or Tayabak (Strongylodon macrobotrys), found only in damp rainforests, usually alongside streams or in the ravines of Luzon, Mindoro, Leyte, and Catanduanes

Species endemism is very high, covering at least 25 genera of plants and 49% of terrestrial wildlife, while the country ranks fourth in bird endemism.

Bringing the numbers down to concrete examples of plants and animals, how many Filipinos know that we have one of the world’s rarest and most visually distinctive deer species?

With its dark brown coat that possesses striking, creamy white or yellowish spots, the Visayan Spotted Deer (Rusa alfedi) is also one of the most endangered deer species in the world, found only in the rainforests of Panay and Negros in the central Philippines.

There is also the Luzon bleeding-heart dove. You can circle the globe but you will only find this medium-sized dove with shimmering, iridescent feathers in shades of purple or royal blue or bottle-green in Polilio Island in Quezon province. And that is just for starters. The most striking quality of this only-in-the-Philippines bird is its vivid blood-red or orange patch of feathers at the center of its white breast—like a bleeding heart.

And did you know that the fabled Ibong Adarna is alive and well in the forests of the Samar, Bohol, Mindanao, and the Sierra Madre Mountains? The Philippine Trogon (Harpactes ardens) or Ibong Adarna as locals call it, does not do magic, but looks magical in appearance.

OUR ONLY HABITABLE HOME

The national list of threatened faunal species was established in 2004 and includes 42 species of land mammals, 127 species of birds, 24 species of reptiles and 14 species of amphibians.

In terms of fishes, the Philippines counts at least 3,214 species, of which about 121 are endemic and 76 threatened.

In 2007, an administrative order issued by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources established a national list of threatened plant species, indicating that 99 species were critically endangered, 187 were endangered, 176 vulnerable as well as 64 other threatened species.

One can get drowned in the thousand-and-one sad and tragic stories on environmental awareness—from climate change horror stories to species extinction scenarios.

But, as the space philosopher said: “we have to start acting as one species with one destiny.” We can begin by being environmentally aware on what is inherently beautiful and exclusive in the Philippine environment, and the urgent need to protect 52,000 species—all rare and wonderful. How well do you know them? How environmentally aware are you?