As we count the months, weeks, days, and hours to the centennial year of the Philippines Graphic in 2027, we will walk down memory lane. With every issue, we will present to our readers snatches of the distant past—captured in reprints of Graphic stories, editorials, columns, illustrations, and photos published during the first five decades of the magazine. It is our way of showing to our readers how unresolved issues and concerns travel across time and plant themselves squarely in our present and future. Hence, the need to learn. In the words of George Orwell: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”—Ed.

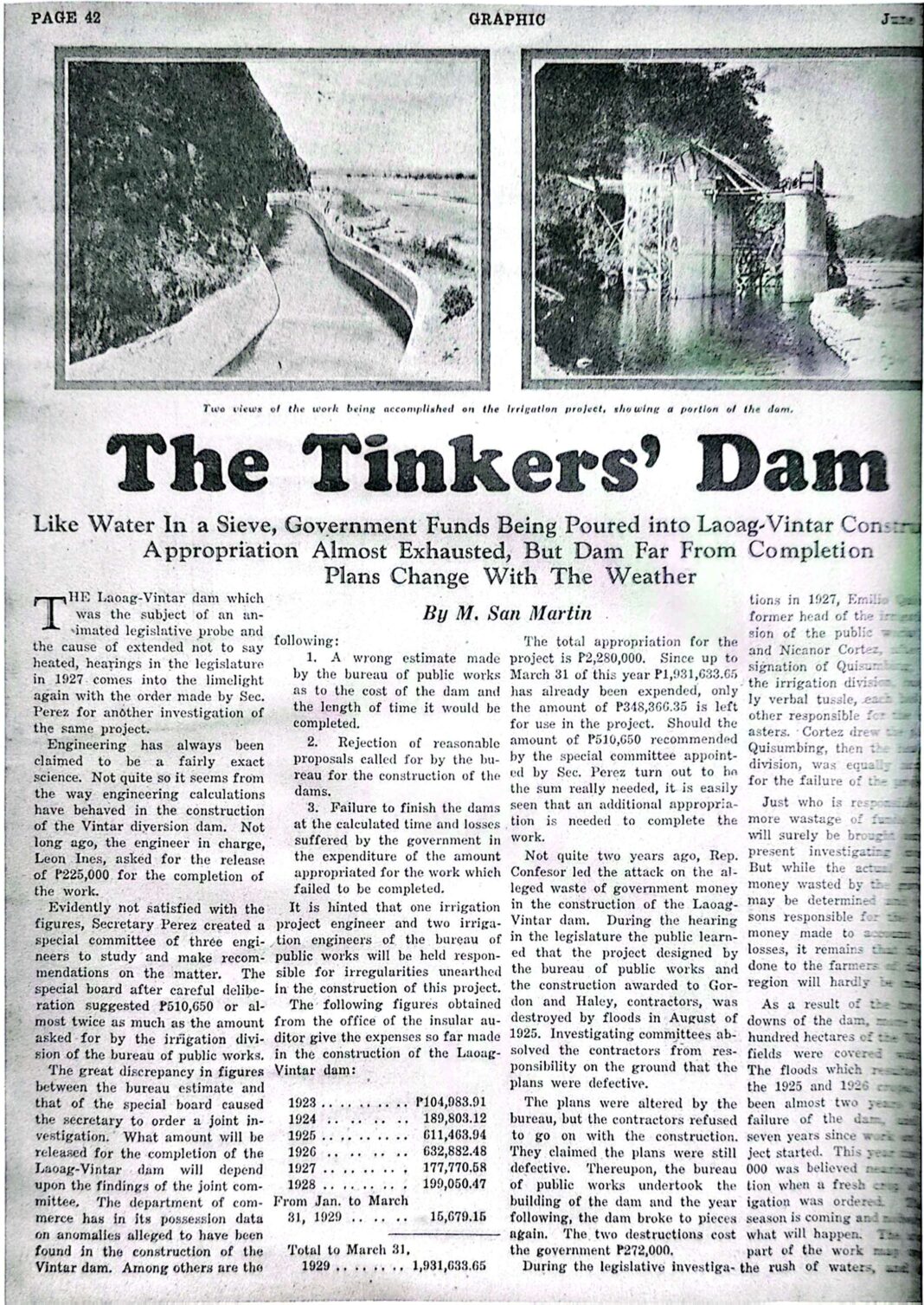

Some 96 years ago, on June 12, 1929, the Graphic magazine published an article titled The Tinkers’ Dam by M. San Martin.

Martin’s report discussed the anomalies in the construction of the Laoag-Vintar Dam, a project of the national government and implemented by the Irrigation Division of the then Bureau of Public Works (BPW) in the province of Ilocos Norte.

Made of concrete, the dam was built in 1926, specifically to raise the water level of the Vintar River. This would have allowed water to be diverted—through a network of canals—in the process, irrigating thousands of hectares of fertile rice lands in the municipality of Vintar and in Laoag City.

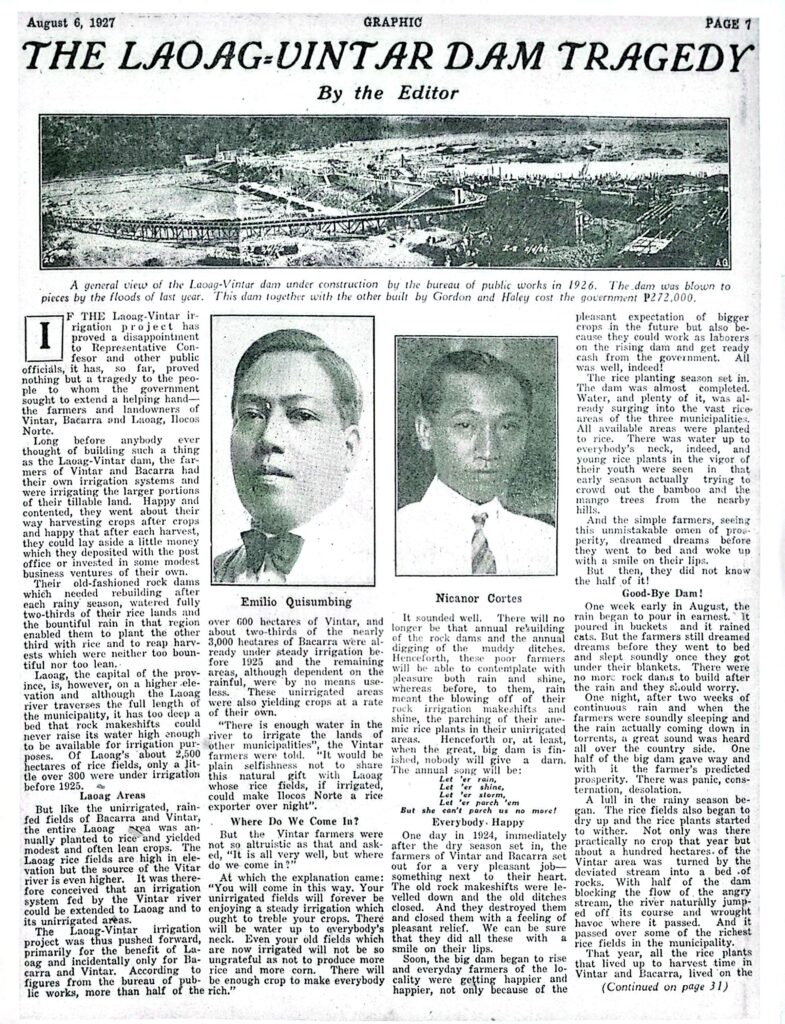

However, the dam collapsed before it could be used. Flooding caused by heavy rains from a passing typhoon led to the inundation of the Vintar River to a point where it overwhelmed the just-constructed dam.

“Representative Tomas Confesor of Iloilo, on July 21, kept his colleagues in the Lower House speechless and open-mouthed while for nearly an hour he charged various departments of the government with scandalous waste of money.”

—Graphic editorial, July 30, 1927

‘The dam project garnered criticism in 1927 for being an “alleged waste of government funds,” after two weeks of continuous rain destroyed it.

CONGRESSIONAL INVESTIGATION

As reported in detail in the July 30, 1927 editorial of the Graphic: “Representative Tomas Confesor of Iloilo, on July 21, kept his colleagues in the lower house speechless and open-mouthed while for nearly an hour he charged various departments of the government with scandalous waste of money.”

The editorial added that Confesor’s “sensational allegations had for a fitting climax a concrete revelation regarding the waste of money in the construction of the Laoag-Vintar dam in Ilocos Norte at a cost of P272,000.

Confessor, the Graphic narrated, then introduced a resolution calling for a “thorough and ruthless” investigation of the entire affair in order to “determine the individual responsible for the waste of public funds in the construction of the dam.”

On July 23, The Herald urged Congress to adopt the Confesor resolution. “There must be no delay in the adoption of the Confesor resolution instructing the public works committee of the house of representatives to probe the repeated failure of the Laoag-Vintar Irrigation system, resulting in the loss to the government of staggering amounts of money. While under construction, the dam was washed away by floods. The Bureau of Public Works then amended the plan, but the contractor refused to proceed with the work on the ground that as amended, the plans were still defective. The bureau then undertook to do work but the dam was again destroyed by the floods.”

The Herald added: “The Philippine legislature has always been very liberal in appropriating large sums of money for public works. This is the time to determine how far the people can trust the present personnel of the bureau of public works in the expenditure of moneys appropriated for the construction of permanent improvements in the future.”

In the succeeding years, several investigations took place, like in 1929, three years after the first collapse of the dam, when the project was again subject to more scrutiny.

“The Philippine legislature has always been very liberal in appropriating large sums of money for public works. This is the time to determine how far the people can trust the present personnel of the bureau of public works in the expenditure of moneys appropriated for the construction of permanent improvements in the future.”

—The Herald, July 23, 1927

BIG TOWN, LITTLE TOWN

Way before the Laoag-Vintar Dam was built, the irrigation systems in Vintar and Bacarra towns had served the farmers well—with rock dams providing two-thirds of their land plenty of water. Of course, they had to rebuild their rock dams after each rainy season. But they were contented with what they had.

According to a 1927 Graphic article, The Laoag-Vintar Dam Tragedy, written by Graphic editor Vicente Albano Pacis, it was Laoag, then still a town in Ilocos Norte, that was in need of assistance. Laoag became a city in 1965.

Pacis wrote: “Laoag, the capital of the province, is, however, on a higher elevation and although the Laoag river traverses the full length of the municipality, it has too deep a bed that rock makeshifts could never raise its water high enough to be available for irrigation purposes. Of Laoag’s about 2,500 hectares of rice fields, only a little over 300 were under irrigation before 1925.

But like the unirrigated, rain-fed fields of Bacarra and Vintar, the entire Laoag area was annually planted to rice and yield modest and lean crops. The Laoag rice fields are high in elevation but the source of [Vintar] river is higher. It was therefore conceived that an irrigation system fed by the Vintar river could be extended to Laoag and its unirrigated areas.”

At the start of the dam project, the Bacarra and Vintar farmers were promised that the river could sufficiently provide for other municipalities, and that it would be selfish not to share it with Laoag.

The explanation given to them, Pacis wrote, was akin to this: “Your unirrigated fields will forever be enjoying a steady irrigation which ought to treble your crops. There will be water up to everyone’s neck. Even your old fields which are now irrigated will not be so ungrateful as not to produce more rice and more corn. There will be enough crop to make everybody rich.”

For Vintar farmers, the promises translated to no more rebuilding broken dams. Not only two-thirds, but all their lands will be irrigated.

They agreed to support the project.

CONTRACTORS, BUREAU OF PUBLIC WORKS

After the dam collapsed, Pacis wrote: “One half of the big dam gave way and with it the farmer’s predicted prosperity. There was panic, consternation, desolation. A lull in the rainy season began. The rice fields also began to dry up and the rice plants started to wither. Not only was there practically no crop that year but about a hundred hectares of the Vintar area was turned by the deviated stream into a bed of rocks.”

Pacis wrote in 1927 that “either the plans or their execution were defective. Both plans were drawn by the Bureau of Public Works. The first plan was executed by private contractors and the second by the bureau itself. Separate investigations conducted by different committees have since exonerated Gordon and Haley, the private contractors and engineers who built the first dam, so that responsibility now seems to be entirely that of the bureau.”

Several more attempts were made to complete the dam. By 1929, the cost of the Laoag-Vintar project had reached P2,280,000, Pacis stated.

ABSENCE OF RECORDS

Outside of the Graphic’s 1927 reportage, there is not much retrievable information that can be sourced regarding the 1927 Lower House investigation on the collapse of the 1926 Laoag-Vintar Dam in Ilocos Norte.

Online research yielded no records, data, or information regarding media coverage and commentary on the 1926 Laoag-Vintar dam collapse scandal.

Outside of the Graphic’s 1927 reportage, there is not much retrievable information that can be sourced regarding the 1927 Lower House investigation on the collapse of the 1926 Laoag-Vintar Dam in Ilocos Norte.

Results of a Google search cites “faulty foundational work” as the cause of the collapse of the dam in 1926.

There is no available information to indicate that any individual or government agency was imprisoned or penalized as a direct result of the dam’s collapse in 1926.

There is no online information on Rep. Tomas Confesor (Mar. 2, 1891-June 6, 1951) as the Iloilo representative who filed a resolution at the Lower House to investigate the collapse of the Laoag-Vintar Dam in 1926.

The present online sources on the late Iloilo Rep. Tomas Confesor focus on his anti-tax campaigns and his role during World War II, with no mention of the dam project.

FAST FORWARD TO 2025

There are many similarities between the controversy surrounding the Laoag-Vintar Dam collapse and the present-day scandal on the government’s flood-control projects.

Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Undersecretary for Integrated Science Carlos Primo David said during the agency’s budget hearing that it is not only the ghost project that is the problem, but also “structures that are poorly situated and exacerbate the flooding.They were constructed, but they exacerbate the flooding.”

Why is it that science and competency seems so foreign in these public works? Bless Ogerio reports in a November 2025 BusinessMirror article that two researchers from Harvard University and the University of Philippines pushed the need “to adopt scientific and transparent approaches in planning and implementing flood management programs.”

For almost a hundred years, the vulnerability of the Philippines to natural forces is being used as a money-making (or money-saving) endeavor—one where thousands of lives, if not hundreds of thousands, are considered only as an afterthought.

“Either the plans or their execution were defective. Both plans were drawn by the Bureau of Public Works. The first plan was executed by private contractors and the second by the bureau itself. Separate investigations conducted by different committees have since exonerated Gordon and Haley, the private contractors and engineers who built the first dam, so that responsibility now seems to be entirely that of the bureau.”— Vicente Albano Pacis, editor, Graphic

Did accountability escape us for a hundred years? And will it escape again for another hundred? Will the events of the present echo once more in the future, just as the past did to us? Perhaps. If there is no retrievable record of our past. If we cannot even claim that “this already happened and we can learn from these mistakes.”

MORE ARTICLES ABOUT THE LAOAG-VINTAR DAM:

These articles are taken from the archive of the Philippines Graphic.

- EDITORIAL: The Laoag-Vintar Dam Scandal (by Vicente Albano Pacis, published July 30, 1927)

- ARTICLE: The Laoag-Vintar Dam Tragedy (by Vicente Albano Pacis, published August 6, 1927)