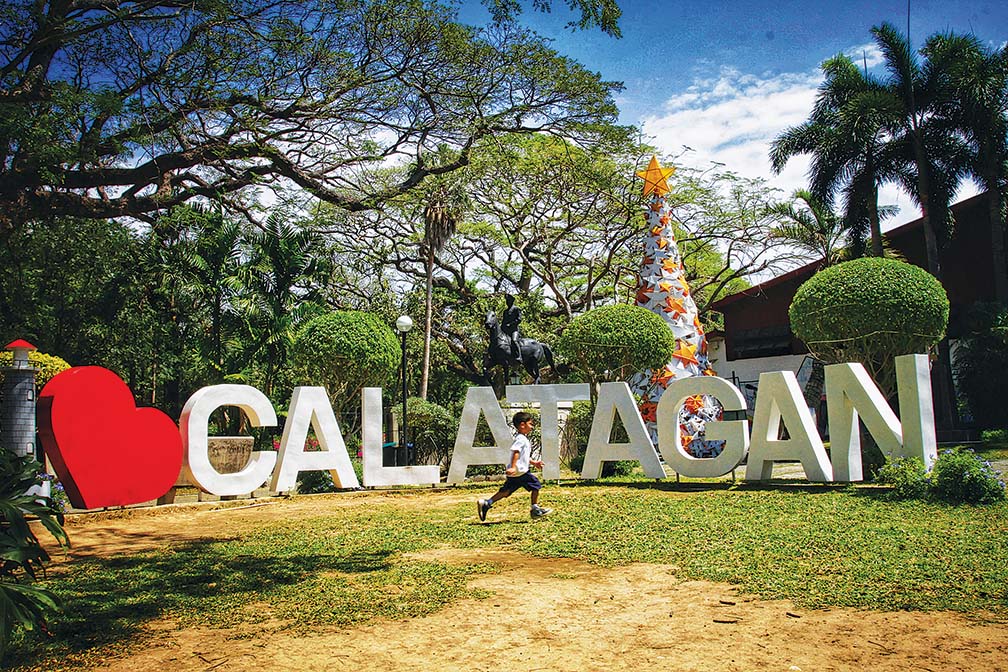

Calatagan town is fast becoming a tourist magnet. Since the easing of travel restrictions beginning in December 2020, it has joined Nasugbu, San Juan, Taal, and the other tourist-friendly municipalities of Batangas province in attracting its fair share of foreign and local visitors.

Lying approximately 110 kilometers south of Manila, tourists usually travel for three to four hours by land to reach Calatagan via the South Luzon Expressway or SLEX.

Those who have visited Calatagan describe it as a diver’s paradise, where one does not have to swim far or dive deep to spot sea stars and sea urchins with amazing colors, as well as crabs, eels, fish, and the prettiest corals, submerged in its crystal clear, blue waters.

The plethora of marine species can be explained by Calatagan being bounded on the south by the Verde Island Passage marine corridor; a passage famously dubbed by the International Smithsonian Institute as the “Center of the Center of Marine Biodiversity in the World” for being at the center of the Coral Triangle, the world’s recognized nexus for marine biodiversity.

Perhaps, this very unique facet has urged Calatagan’s mayor to choose a very tempered and calibrated response to the rush of tourists and land developers that, if left unmonitored, can threaten to spoil the pristine beauty of this second class, coastal town of some 60,000 people spread across 25 barangays in the most southwestern part of Batangas province.

SUSTAINABILITY TRAILBLAZER

Meet Peter Oliver M. Palacio, the visionary mayor of Calatagan. He has trailblazed a strategy called “balanced development”—one that puts premium on the protection and conservation of Calatagan’s rich coastal and marine resources, while promoting agriculture, fisheries, and lately, ecotourism.

In the words of Palacio: “Calatagan’s strength as a municipality lies in its being way ahead in pursuing a circular economy. It is the restorative and regenerative way of achieving sustainable, balanced development, where even biodegradable wastes are turned into compost to promote organic farming, for example.”

At 56, Palacio has long appreciated and implemented programs that protected the aesthetic beauty of Calatagan’s relatively healthy reefs, seagrass beds, and clean waters. “It’s a paradise. In Batangas, we are the only one with reefs. This is the character of Calatagan. Other towns don’t have reefs. We have beautiful reefs. In many areas in Batangas, it’s a steep drop. But, no reefs.”

Continued Palacio: “There are also times when butanding or whale sharks are spotted by fishermen in the waters of Calatagan. Maybe because of the plankton. They (whale sharks) eat plankton that’s why there are sightings of whale sharks here.”

It comes as no surprise that for two straight years during the Duterte administration, Calatagan, under Palacio’s watch, became an awardee of the Malinis at Masaganang Karagatan by the Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources.

He admitted, however, that having beautiful beaches and a clean and healthy coastal and marine ecosystem did not happen overnight for Calatagan.

The coastal municipality once suffered from destructive fishing activities like the use of active gear by commercial fishers, as well as small fishermen engaged in illegal dynamite and cyanide fishing.

“When I first became mayor in 1998, we started to protect the area,” Palacio said, adding that the safeguarding of Calatagan’s marine ecosystem has been a major function of the municipal LGU since then.

THE EARLY YEARS

Although born in Manila on Feb. 11, 1967, Palacio was raised in Calatagan, Batangas by his parents, the late Exaltacion M. Alaras and Pedro M. Palacio, Jr., former Mayor of Calatagan.

Oliver, as Palacio is called by friends and associates, remembered the Calatagan of his youth as radiant with vast sugarcane plantations and abundant marine life, being both an agricultural and fishing town.

Over the years, farming families continued to grow other crops like rice, corn, coconut, legumes, and a variety of vegetables.

Calatagan’s rich municipal fishing ground allowed the town’s small fishers to thrive and benefit from the ocean’s bounty.

Inadvertently, in the past, Calatagan’s fishing grounds became an “unwilling” host to “visiting” fishermen from other towns in Batangas and nearby provinces.

As a young man, Palacio considered himself a farmer and a fisherman, spending his days tending to his family’s sugarcane crop or going out fishing.

He said he would fish to a point that his late mother scolded him for not coming home on time. “My mother was the stricter one. My father, he would only smile and laugh.”

The untimely demise of his father, however, compelled the young Palacio to run for public office. He became mayor at the age of 30 in 1998.

LEARNING FROM FATHER

According to the mayor, he has learned a lot from his late father.

Recalled Palacio: “When I was a teenager, my father taught me one valuable lesson: Learn.”

That is why programs and projects under his watch focused on fisheries, he admitted.

Palacio said that he developed a good grasp of Calatagan’s marine ecosystem from his fishing days. “I know the situation before.”

Today, he said, they have data to back up their observations. “There are nongovernment organizations and international agencies where you can get them,” he said.

He further expounded: “I, for myself, naranasan ko yan [I experienced it]. My father told me that when they were still young, they were bullish when they went fishing. They didn’t immediately pick octopus. Because there were plenty of fish to go by. When it was my time, in the 80s, whenever we saw an octopus, we grabbed them.”

In the 60s and 70s, he said, fishermen would only start fishing on their way home. And yet, they go home with a bountiful catch. They don’t even have to catch octopus,” he said.

He stressed that he knew the fish catch in Calatagan was already dwindling when he became mayor in 1998. “That’s why it became our mission to protect the ocean.”

Palacio likewise said that what he learned from his father, he has passed on to his children. He has been blessed with seven children—Princess Charmaine G. Palacio, Fatima Juliana P. Abella, Czarina Patricia G. Palacio, Pedro G. Palacio IV, Peter Elwin G. Palacio, Peter Oliver G. Palacio, Jr., and Juan Miguel G. Palacio.

“Even when I am busy, I make it a point to have time for my family. No matter how busy I am, I have time to talk to them. I teach them what I’ve learned through my experiences in life,” he said.

According to Palacio, he tries his best to teach his children the realities of life, the way his father taught him.

“My father once told me, how can you manage if you don’t know how things are done? For example, planting sugarcane. So, he taught us how to do it. We were working together with other farmers, planting sugarcane. Farming, planting, weaving, cultivating, and harvesting. I experienced all of it. That was the principle my father taught me. How can I teach things that I don’t know?” he said.

Proudly, he said his eldest is now a doctor of medicine. The second completed a course on International Hospital Management at St. Benilde, including an on-the-job training in the United States for one year.

Palacio said he lets his children decide which course they want to take. “I told them, study, take the course you like. I will not stop you. You see, many people became successful because they love their job. On the other hand, many people became failures because they were forced to study a course that they did not like. I don’t want my children to blame me later on,” he said with a laugh

DEDICATED LOCAL CHIEF

Palacio, like his late mayor-father, prefers to be a local chief executive. He has shunned calls to run for congress, saying he is more of a municipal mayor than a lawmaker.

He could have run for Congress after his nine years as mayor from June 30, 1998 to June 30, 2007 but decided against it.

“I was never a Congressman,” he said, adding that another reason is the fact that it is not really his forte.

The mayor was so successful that he consistently won in the local elections, defeating other candidates every time, thus serving for three straight terms.

Due to the prohibition on term limits, Palacio stepped aside and his wife took the driver’s seat for Calatagan for nine years.

“I prefer to focus on Calatagan because if I leave, I am afraid it will be a waste. The opportunity, the good things that is happening now in Calatagan may be lost if I decide to leave. It is common knowledge that when a new leader takes over, the direction also changes. It will be such a waste,” he explained.

He compared Calatagan to an airplane that has taken off the ground. “You don’t change pilots in the middle of the flight. Because there’s always this risk of crash landing if the pilot suddenly leaves.”

Early on, Palacio believed that governance was to a large extent defined by people support. The community was paramount for the local government to be able to implement programs and projects that protect and conserve the town’s natural wealth.

According to the mayor, without the community’s help and support, it would be difficult for the local government to enforce environmental laws.

“You can’t implement all these (environment) laws at the same time. If you do, it will be hard, chaotic,” he said.

Palacio noted that to encourage fisherfolk to avoid illegal fishing methods, the Calatagan LGU gave away fishing boats and fishing nets to convince them to do fishing the right way.

He added that for the people to adjust gradually, environmental laws against illegal fishing were enforced one at a time.

“We started with dynamite fishing. We contained it. There were plenty (dynamite fishers). We have local dynamite fishers, and there are also dynamite fishers from other towns,” he said.

According to Palacio, whenever they catch violators, he would talk to them and ask: “Why do you come here to Calatgan to do dynamite fishing? Their answer: Mayor, we no longer have fish in our area. That is what we never want to happen in Calatagan,” he said.

He said after containing dynamite fishing, the campaign against cyanide fishing came next. But it became much easier.

CARROT AND STICK

While some are supportive of the programs, the mayor said some were defiant of the changes being introduced by the local government, admitting that sometimes, he had to be a disciplinarian.

Palacio said that in the beginning, he made examples of illegal fishers to prove a point to the people that the campaign against illegal fishing in Calatagan is serious.

“After we caught some and put them behind bars, just once, the others stopped. They realized we are really serious,” he said.

According to Palacio, some of the boats of illegal fishers from other towns who were caught in their illegal activities, after being found guilty in court, were repainted and used as bantay dagat (protector of the seas) service boats.

“What we did is, I wrote a letter to the judge and asked for the boats. We repainted them and used them for our volunteers. In 2017, we have plenty of boats for our bantay dagat,” he said.

Lastly, he said the local government enforced the use of appropriate fish nets. “we confiscated the fish nets that catch even the small ones,” he said.

Gradually, the mayor said volunteerism was introduced to the local communities.

“What we did is, we made those illegal fishermen in Calatagan the bantay dagat. Because they used to do it, they have no problem stopping others from doing it,” he laughs. “They became our volunteers,” he said.

He proudly said the coastal communities do not receive salaries or wages as volunteers. But being volunteers, he said the people became proud of their contributions.

He said because of their help and support, volunteers in return receive insurance, and a little token every December.

PARTNERSHIP WITH STAKEHOLDERS

Palacio defined his style of leadership in Calatagan as one anchored on the principle of partnership. “I told them, Oliver can’t do it alone. Let us do it together. We are partners,” he said.

The mayor explained that while the local government will do its part, the communities are also expected to do their share.

He cited tourism as an example. “I told them, we will do the infrastructure projects, but you have to do your share, too.”

Palacio said the coastal communities who are now benefitting from ecotourism have volunteered to do coastal cleanup on a weekly basis.

“Every Wednesday, you will not see tourist rafts going out. Because all of them are doing the coastal cleanup. While others do it every September, once a year, here in Calatagan, we do it every Wednesday,” he proudly stated.

Aside from his position as local chief executive of Calatagan, the mayor has time for other endeavors. He is currently the vice president of the League of Municipalities of the Philippines–Batangas Chapter.

He is also the president of the Batangas Federation of Sugar Planters’ Association and sits as a member of the Provincial Agrarian Reform Coordinating Council (PARCC) of Batangas.

Currently, Palacio is also the Chapter President of the Balisong Shrine Club.

SUCCESSFUL COMEBACK

In his successful comeback bid, Palacio came up with an innovative idea to focus on ecotourism. That is when the idea of popularizing Calatagan’s precious fish, the kuyog (rabbit fish) was born.

Scientifically called Siganus canaliculatus, kuyog is endemic to Calatagan’s healthy coastal environment. In the entire province of Batangas, it is only in Calatagan where kuyog can be found.

“We capitalized on what we have that others don’t. Kuyog. It is delicious. Fishermen in Calatagan produce dried kuyog. We popularized kuyog to promote our white sand beaches in Calatagan,” Palacio said.

Having spawned the idea, Palacio led members of the Calatagan LGU in launching the Kinuyog Festival, held every year during the celebration of the Founding Anniversary of Calatagan.

According to Palacio, the promotion of “kuyog” as well as Calatagan’s beautiful beaches and resorts happened by word of mouth and through the help of social media.

“Because of social media, tourists started to come to Calatagan again,” he quipped.

JOBS, JOBS, JOBS

Calatagan’s booming tourism industry is opening income and livelihood opportunities to its poverty-stricken residents.

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), Calatagan’s poverty incidence in 2000 was 51.28% or half the population living below the poverty line.

More than 20 years later, the municipality’s mayor is pinning his hopes on tourism playing a big role in lifting his constituents out of poverty.

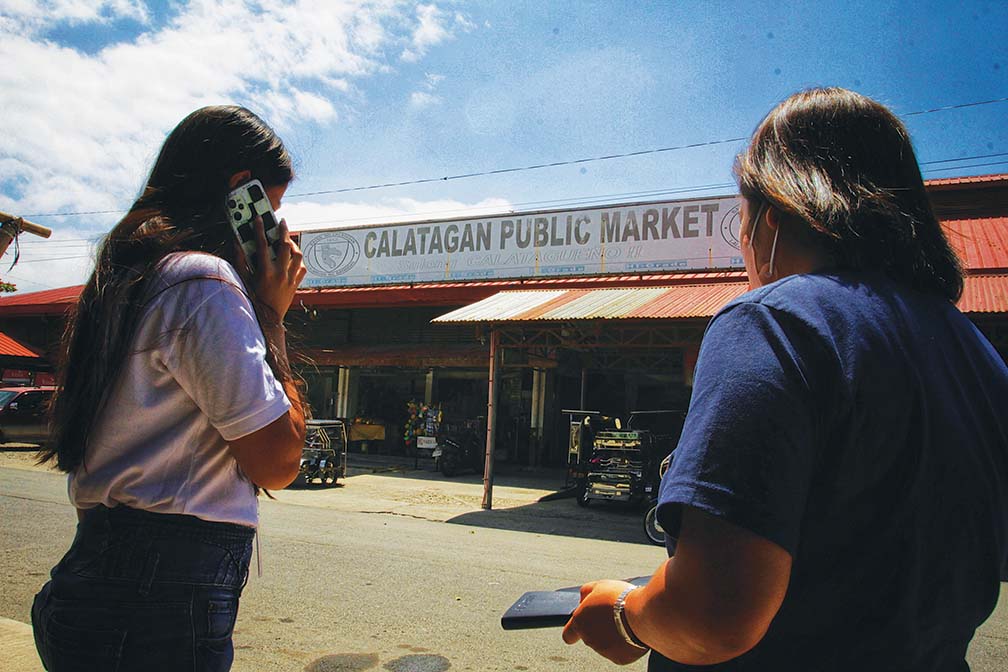

“How can we increase our income? Tourism. We have a population of 60,000. That is not enough to sustain the public market. That is our barometer, the public market. Once the vendors stop selling in the market, business stops. That is a problem,” he said.

But with tourism, the number of buyers grew. “With tourists, the buyers increased,” Palacio said.

In 2016, the year when the local government under Palacio’s leadership started to focus on promoting ecotourism, overnight tourists stood at 21,627, with same-day arrival tourists at 41,723. By 2019, overnight travelers reached 114, 511.

And while the COVID-19 pandemic might have dealt a blow on the country’s overall tourism industry, tourism figures in 2022 show that Calatagan is slowly but surely getting back its tourists, with overnight tourists peaking at 17,143 and same-day arrivals reaching 14,369.

Palacio intends to make Calatagan food self-sufficient. “That is why from the market, (we are) going again to the farms. The food that is sold in the market comes from our farms. That is why we will again strengthen our agriculture and fisheries.” he explained.

DOMINO EFFECT FORMULA

While the local tourism industry will benefit from an increase in tourist arrival, Palacio said farmers will also benefit as the demand for food will also grow.

In fact, he said the farmers will be the main beneficiaries of a vibrant tourism industry.

“Our farmers are the suppliers of the food in the market. They are the food producers.”

Palacio stressed that with a healthy economy anchored on tourism, peace and order will follow. “That is why I’ve always told our fishermen: Take care of our waters. So that we will have a source of seafood.”

Added Palacio: “It is all about how you manage things. Me, I can be seen walking around town with no bodyguard. I am not the kind of politician with 12 bodyguards. From 2007 to 2016, I can be seen going to the market alone. I don’t even like a police escort. But the chief of police insists because, he told me, whatever happens to me, it will be on him. Siya ang malilintikan [It will be his head].”

Peace and order become problems when there is hunger and poverty. But if people have jobs, definitely, crime will go down, Palacio further explained.

To generate jobs, Palacio said the municipal government required each tourist raft to have at least one lifeguard.

“That’s why you will see no bystanders. They are now working as lifeguards. Before, you can see a lot of bystanders, even doing nasty things like vandalizing our covered court. After they were hired, we got rid of the bystander problem because they are reserving energy for work the following day. They have work,” he said.

Palacio puts finding jobs for people as a major priority, because “an idle mind is the playground of evil.”

“What I really envision is not just agro-tourism, but a balanced development— meaning, we have agriculture, we have tourism, and we have industrial areas. Before, people from Calatagan and other towns in Batangas go to Cavite, Manila, and Laguna for work. If we have an industrial site here, there will be adequate jobs for our people,” he said.

Palacio said that the demand for skilled labor in Calatagan’s local tourism industry is beginning to be felt. He noted that there is now a scarcity of carpenters and other skilled labor because of developments in Barangays 1, 2, and 4 of Calatagan.

“Before, there are shanties in the coastal areas. Now, they have concrete houses. Tourists want to stay overnight,” concluded Palacio.