I met Edith L. Tiempo on the night I won my first national literary award in 1979, from Focus Philippines. She headed the panel of judges. My story “Old and Unborn” placed third, but having her as one of the judges made me feel like a first prize winner, especially when I later learned that I was in fact second in her short list. For someone who was simply content to have her short story published, and had no expectation of winning any award for it, that was incredibly gratifying.

I had read “The Dimensions of Fear,” and marveled at how Edith Tiempo could speed up my heart rate and make me break out in cold sweat, in fear of being exposed as a dishonest man—because yes, with her keen eye for significant details, and her total emotional identification with her characters, Tiempo had magically transformed me into her protagonist Agujo, the timid, reasonably decent schoolteacher who steals and faces the terrifying certainty of discovery.

I am no poet, and at that time, I read very little poetry, but reading Tiempo’s “Bonsai” gave me not just palpable joy, but lucid pleasure, arising from the fusion of sound and sense.

I knew, of course, that she founded and co-directed the Silliman University National Writers Workshop with her husband, SEAWrite awardee Edilberto K. Tiempo. She is listed in the Princeton Encyclopeida of Poets and Poetics, Princeton University, New Jersey; the International Authors and Writers Who’s Who, 8th edition, Cambridge, England; the Contemporary Living Poets in the English Language, London, and the Marquis’s Who’s Who in the World, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Her literary works have been included in anthologies of Midland, Random House, USA.

Not surprisingly, I could not wait to meet her. But when the time came, on awards night, I could only smile and thank her. I was too shy to say anything more, but I was happy enough meeting her briefly. If anyone had told me that in a couple of years, I would be calling her Mom, I would have said “Dream on.”

When I started writing, I knew about writers’ workshops—there were only two, the UP National Writers Workshop and the Silliman University National Writers Workshop—but never had the nerve to apply. I heard so many horror stories about writers’ workshops then, how fellows would be told to just go home and plant kamote.

A few months later, I received a letter from Dr. Edilberto Tiempo, offering me a fellowship to the Silliman University National Writers Workshop. Unbelievably, I began concocting excuses for declining the offer. I could not take a leave from my job. Who would take care of my baby? Who would feed my cats? Anything to avoid having my story read and critiqued by a panel composed of the Tiempos, Kerima Polotan, Leoncio Deriada, Francis Macansantos, and other fellows who surely knew more about writing than I.

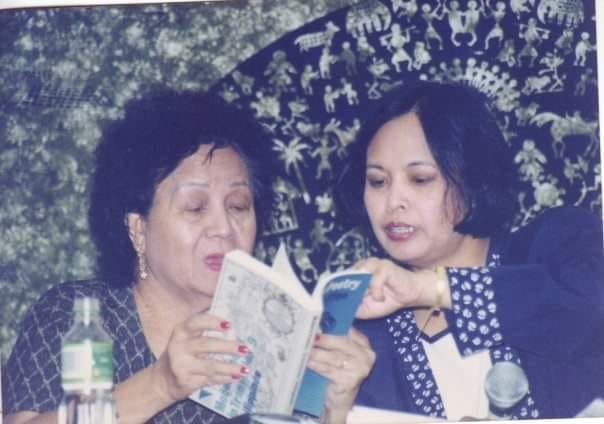

Long story short, I went, fell in love with Dumaguete, fell in love with the Gentle People, exemplified by Edith herself, who had the rare knack of pointing out a literary work’s weaknesses in the gentlest manner, and never failed to offer helpful suggestions. She was the perfect foil for Ed Tiempo, who did not pull his punches. He would start a discussion by saying “The problem with this story…” and she would interrupt and say “The good points first, Dad.” She advised the author of a story that suffered from self-indulgence that “it might help to get out of the first person point of view.”

“The story doesn’t move on only as a story,” Edith often said. “Every incident should be so dramatized, so conceived that it contributes to the theme, revelatory toward the theme. That’s a terrible thing to remember, you know, you can never create an incident until it is a meaningful incident, that is, it helps to reveal your concept.”

Yet Edith always grasped the possibilities of even a story that does not rise above the literal level. In one memorable session, Edith saw, in a piece that was nothing but a blow-by-blow account of a failed romance, three possible concepts:

1. Home is a state of mind engendered by the self in response to circumstances whether human or situational.

2. The battle is always pitched not against the enemy but against one’s self.

3. With the pain of losing, one gains an insight into human frailty toward which one learns to be compassionate.

The fellows, and, admittedly, the other panelists, could only look at one another and think, “Where did she see that?”

Ed Tiempo would shake his head and say, “What you are saying is not here (in the text).”

“Yes,” she would agree, “it is not here yet, but it is possible.”

Edith always saw the potential story alongside the actual story that was right before her. It was always a point of contention between her and Ed, something that always triggered what we used to call “the showdown”: that one session, which usually happened during the third week, when the differences in their critical approaches would come to a head, with Ed pounding the table and saying, “The trouble with you is you are too kind!”

Some more gems we learned from her and we remember to this day:

“The writer must take care of everything. He must achieve resonance, a multiplying of meaning.”

“Lines in a poem must be lean but full of substance, as against the fat, flabby lines, or the starved line.”

“Let the concept be the main concern, even in an imagist poem.”

“A story needs room in which to echo, to reverberate.”

“Fine craftsmanship and thin substance is actually much ado about nothing.”

“The conscientious writer’s great task is to preserve for the human being his finest and best self.”

What was she like when she was not writing, or teaching? When she wanted to relax, she played solitaire. She loved reading detective novels. She enjoyed watching “Tom and Jerry.” She couldn’t get enough of the halo-halo of Chow King, and anything sweet. Whenever we paid her a visit in her hilltop home in Montemar, Sibulan, she would serve us the deadly combination of ice cream, brazo de mercedes, and Coke—regular Coke. She sang racy songs and told bawdy tales and jokes, but only after Dad Ed had passed away.

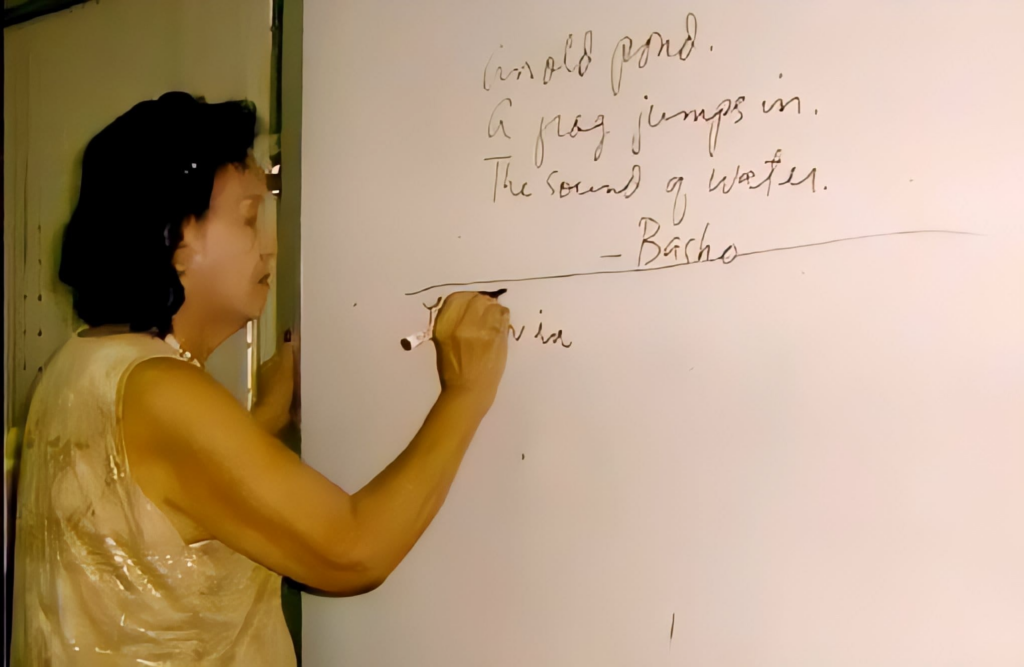

She admitted that sometimes she surprised herself with her own remarks. She once referred to an unwholesome fictional character as “that sunnamagan.” During one session, as she turned her back to write something on the whiteboard, she heard a camera clicking away. She turned to the writing fellow who was taking her picture, wagged a finger and warned her, “careful with my butt.”

Part of her extraordinariness was her insistence on being treated as an ordinary person. Whenever she introduced herself on the first day of the workshop, it was always “Mom, call me Mom.” Her last wish was again to be treated as an ordinary person—to break away from tradition and not to be buried in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, as befits a National Artist. Like any ordinary Dumagueteña, she wanted to be laid to rest at the Dumaguete Memorial Park, beside her beloved, our beloved, Dad Ed.

In my eulogy at the memorial tribute to Mom Edith held at the CCP, I said “Mom, you got your wish. You’re now with Dad. We shall stop worrying about you now, and start worrying about ourselves, and how, in the name of all that makes sense, we can ever go through life, without you.”

We need not have worried. It has been 12 years since she passed, and we do miss the sound of her voice and laughter and her tight bear hugs, but we are never without her, because we carry her around with us wherever we go.