As Zac walked towards the archives building, he noticed a bent betel tree growing dangerously close beside an old Ficus. Both old and young trees competed for the sun. He treaded this path before, with friends, but did not notice anything out of the ordinary. Lately, he began seeing things, their shapes and colors, hearing voices, noting smells, actuations and motivations.

“Can you help me access microfilmed news items between these dates please?” he asked the desk assistant, scribbling on a pencil the period. Zac’s fingers sounded like hoof beats on the table. He breathed deeply trying not to look like someone awaiting a medical diagnosis. His eyes wandered through the archival collection. What lives were lived and lost in those files, now peppered with dust from disuse and neglect! At the rack’s far end, two teenagers tenaciously argued the way they waved their hands, albeit speaking in lowest tones. Lovers’ quarrel, Zac bemused.

A week ago, Zac was a bright but happy-go-lucky law student. He studied “enough to pass exams” in his words, though his professors knew he could do more. His knack for exposing contradictions, earned respect from his professors and irritation from peers who regarded him a “rabble rouser.” His class analyzed a case involving an American couple, who, because of their religious beliefs, were charged of defacing government property – in particular the metal plates of their own car by sticking a red tape over the state motto embossed at the car plate’s bottom: “Live Free or Die.” The couple said only the Creator can tell them that and not the state. Zac raised his hand and smirked: “It’s ironic, professor, that the accused understood the motto better than the state prosecutor himself. The accused wanted to live free enough to cover the motto they don’t believe in even if that meant violating the law.” The professor’s eyes widened as he mumbled: “You’re right!”

After school, Zac went straight home. His parents were not there. Food was left on the table for his supper. He decided to write case abstracts, as was his wont at night. A teacher tipped the habit of summarizing cases can make the bar exams look like a “walk in the park.” As his pen had barely enough ink, he proceeded to his father’s law office in the other room. Zac noticed the top drawer of the old metal filing cabinet near the main desk was a tad bit open. His dad may have forgotten to lock it, albeit unusual for him, as he always locked his things out of habit. Zac tried to push the drawer but it did not fully close. He pulled the drawer to check if there was something inside that held it from being closed. As he was about to push it, his eyes caught an old folder with his name on it. He could have brushed that aside were it not for a child’s clothing tucked inside the file. Zac’s curiosity got a hold of him and, with goose bumps all over, decided to take the folder with him to his room.

His heart pumped in what felt like a tiger wanting to jump from its cage. He dimmed his light, and looked out the window in case his parents were outside. There was silence in the garage. He placed the old baby shirt and underpants on the table. As he flipped through the pages, he instantly recognized what could only be a court order. A word popped from the page: “adoption.” His heart stopped beating as his consciousness twirled around the room. He could see everything from the ceiling down. “No wonder,” he said to himself. His parents could not tell him in which hospital he was born. Or why his skin tone was a tad bit darker than them. It’s not even about that. There was a certain awkwardness, exaggeration even, in the way his parents doted on him. He had bigger toys than boys his age, went to more places on summer breaks than his classmates. Yet his parents never visited, and neither was he close to his aunt Lilia, his father’s sister, who lived two towns away, in the small village of Dalanon. He saw his aunt once at the hospital when his parents came by for a visit after her surgery. That was about the only time he can remember, though it’s possible he forgot the other occasions.

Zac could not read past the main import of the adoption court order. He felt his mind was in a blur. He tried to scan the pages but decided to read more when his nerves settled. His hands shook like they had minds of their own. He tossed and turned on his bed for the most part until his parents arrived, laughing and giddy from a party.

Zac’s father was a famous lawyer in the city. He was a squat yet amiable man with thick sideburns. If he did not practice law, he would have made a name for himself in politics. “Everyone a friend” was his motto. He walked the talk, the way he treated everyone alike. No human could do that, Zac mused, but his father was not an ordinary man. His father had a way with people, unlike Zac who chose whom he spent time with. His father played volleyball at the dockside with port laborers, joked with fish vendors, and regaled prominent wives with boogie-woogie where his father’s right arm became the crane from where ladies spun and tumbled.

Zac’s mother was a homebody with expertise on patisseries and vegetarian dishes. Zac thought it was good he did not take on her sweet palate, though he savored her deserts out of respect. Her vegetarian dishes were one of a kind. “Why don’t you open a vegetarian shop, Mom?” he asked her. She thought cooking for the family was enough. “Your dad and I needed to rest for our ballroom dancing—the only exercise we can agree on,” she winked looking lovely in her newly trimmed hair that made up for more than a passing resemblance to Twiggy. A homebody by day, Zac’s mother transformed herself into a glittering socialite at night. She and her husband were the brightest stars in the constellation of their small city’s parties.

The night Zac found the folder, his parents came from a fund-raising event for blind people. They were active spokespersons for cause-oriented organizations, a fact Zac was proud of. That night, he was not sure. He doubted his parents truly liked to help people, or was all the philanthropy just for show? But no, they “are good people,” he reprimanded himself. He should know that more than anybody. His parents were everything to him. He became a good boy, at least he thought so, because of them. He screamed and covered his mouth with a pillow, not that he cared. His parents lied to him. What else did they hide? Or want not to hide? Did his father want him to find out by purposely opening the filing cabinet? Why didn’t they tell him directly? And sooner. Zac’s mind was a misaligned kaleidoscope. A rogue missile, was more like it. He was no longer sure he knew his parents.

He waited for his mom and dad to be still in their room. He tiptoed to his bathroom and read further the file from there. Despite his few semesters n law school, he found it hard to comprehend the adoption order. The images did not add up, though the facts were logically arrayed in a neat way, the way judges do: Zac was an orphan. The whereabouts of his biological mother is unknown, leading the social welfare officer to surmise she might have died. His biological father met a “gruesome” death early morning of 5 December 1982, but not much elaboration followed. Then, the baby was placed in an orphanage where his adopting parents found and took him. From a tender age, he answered by the name of “Atok,” but surmised his adopting parents chose “Zachary,” “Z” being farthest from “A.” Zac’s analytical mind could not put together two and two why he was picked: was it his smile, or helpless demeanor? Friends had told him in his unguarded moments, Zac would have this hapless look of a lamb about to be led into a slaughter house. But then, that does not seem to be a strong reason to adopt: to help maybe, but not to make him another person’s child. What gave him an edge over other kids in the orphanage? He looked at himself in the mirror. That face looked plainer than any boy on the street save for the daring mullet hairstyle. It could not be his looks. There was nothing spectacular about him.

The next thing, it was day time. A faint light entered his bathroom window silent as a hungry cat. He had slept on the bathroom floor. Stray papers were scattered around, and the file was left open near his head. He noticed a tiny penciled scribble above the word “gruesome:” “stoned.”

II

Zac’s stomach grumbled. A bowl of noodles seemed a convenient fix. After sneaking into his father’s office to return the file, he pasted a note saying he will not be home for lunch. He went straight to the “panciteria” where he and his friends would hang out to dissect controversial legal cases. Though nearly noon, the place was not as packed as their last visit. The staff recognized him, but they let him be by himself as he slurped his hot mami. He put his dark glasses on, and took a deep breath. He thought of his aunt Lilia in Dalanon.

The bus to his aunt’s place took longer than expected. A recent landslide partly crippled the only artery that connected his city to the junction where Zac would stop to take the dreaded foot path to the isolated seaside village of Dalanon. The place had no access to the highway except through a ribbon of flood-prone earth framed by prickly weeds. He wondered why his aunt chose to stay in Dalanon sewing dresses for villagers when she could just have easily opened a shop in the city with the help of her brother. She’s not beautiful but “has her beauties,” he recalled a phrase used to described his favorite poet. His aunt Lilia is a middle-aged woman who’s kind and modest, and not cantankerous, unlike others who did not marry. Talking of lifelong commitments, how could she marry if she’s chosen to rot in this heaven-forsaken place?! Zac’s libertarian training came to the fore, as he brushed aside his previous thoughts with “of course, one lives where one is most useful and happy.”

It was late afternoon when Zac arrived in Dalanon. His pants were strewn with mud and amorsecos, his hair disheveled and his eyes puffed like those of a bulgan fish. His aunt saw him first. She was at a local bakery operated by her friend Katang, a place Lilia felt most at home in. It was there she could relax and laugh in between dressmaking deadlines. It is with Katang where Lilia could let her guard down, where she could speak her mind out without being judged. That day they indulged in the latest gossip over small goblets of tuba.

“Zac! What wind brought you here?” Lilia hollered, and embraced her nephew like a lost son.

“I’m famished Aunt Lilia, I haven’t eaten for days.”

Katang, who was within earshot, interjected, “I have paksiw, and some boongon. I’ll prepare supper for us all.”

At the dinner table, Zac fibbed he’s taking time out from his girlfriend who had become too clingy for comfort. “I don’t want her to think I’m husband material. I need to do many things,” he said while looking at the ceiling. His Malayan complexion is belied by a near-perfect straight nose.

The two ladies looked at each other, and ogled: “Pregnant?”

“No Auntie, nothing near that.”

Zac slept like he had not slept in a long time. He thought he heard himself snoring. He saw a lake and heard shrieks and shouts of yawa meaning “devil!” The earth spun, the way it spun when he read “adoption” in the file. “No, no!” He moved his neck from side to side, shouting. He awoke from a slap his aunt gave him. “What happened?” “You had a bad dream,” his aunt said, then patted her hand on his head: “Calm down.”

“I’ll go back to the city the first opportunity before dawn, or my parents will call the police for my whereabouts.”

“Better sleep, and I’ll prepare an early breakfast for you before you leave,” Zac’s aunt sounded reassuring and relieved.

III

The rest of the week was uneventful. Zac hardly talked to his parents. “School work,” he said. They thought he was in a phase: Lover’s angst or an intellectual glitch akin to a writer’s block, perhaps. They let him be. They did not poke into his unconscious as solicitous parents do. He had mood swings, they ratiocinated, but got over each one in time. They planned to take him to Hongkong during the summer break.

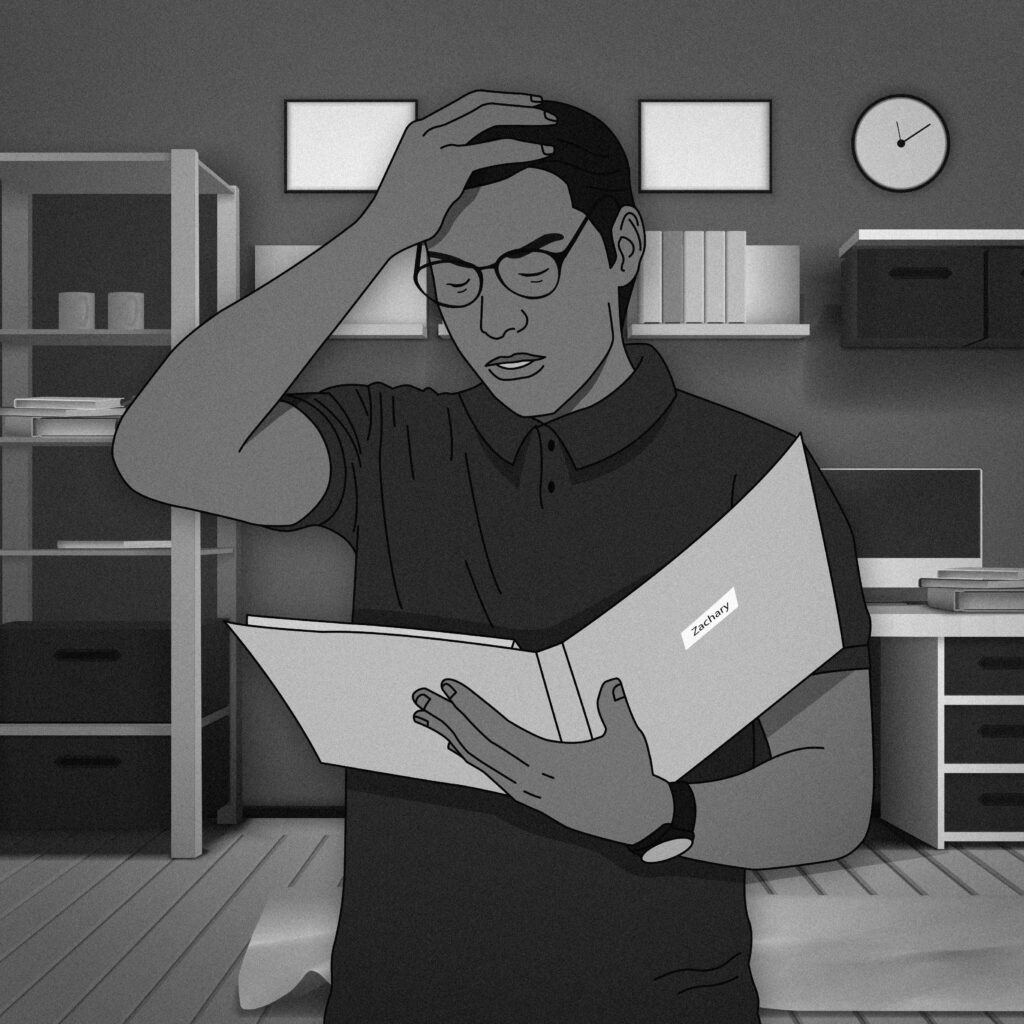

Zac dreamed of the lake again. He stood in the middle of it at midnight. The waters clasped his knees. Cold gusts of wind licked his neck like puffs from a dying cigarette. He could discern the glimmerings of the setting moon on the lake’s surface. Ripples broke the calm as wavelets chased one another. Then, Zac heard an exchange of voices. At first polite, the tone became blurred and rugged like the jagged mountaintops surrounding the lake. Hurried footsteps, strained breathing, and pleas for mercy were heard as Zac felt himself pushed: “Run, Atok! Run!” The screams became shrieks, and the eyes of the ripples became craters as large stones were hurled in. Zac pushed himself away but his feet were held back by the lake waters.

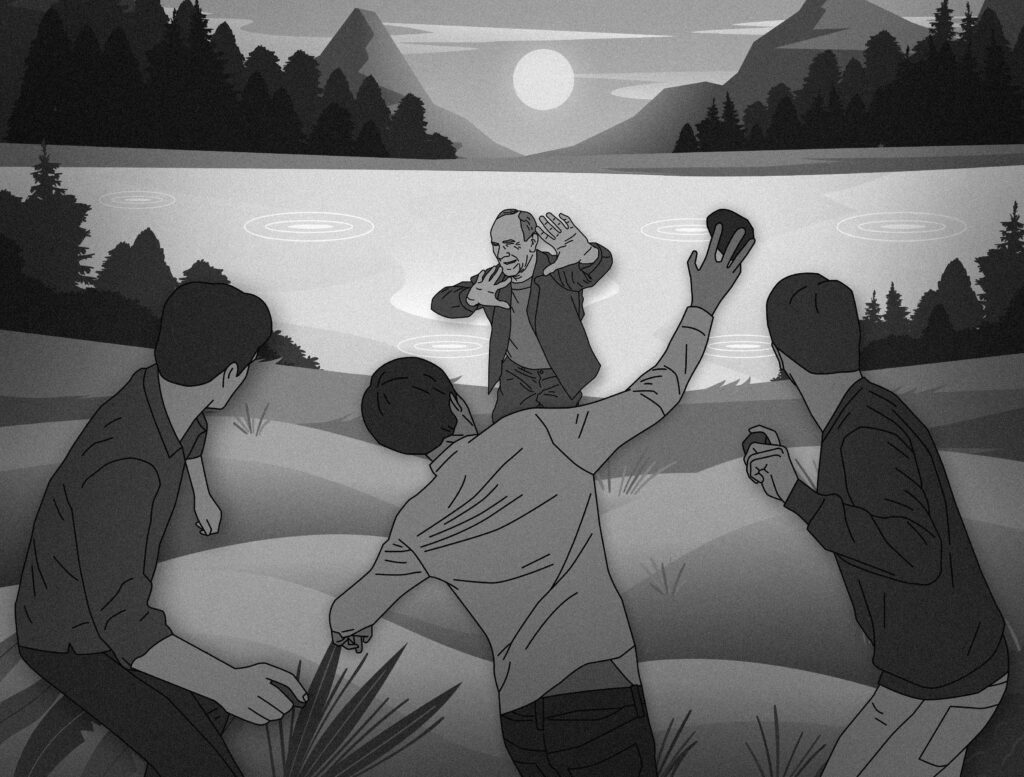

At breakfast he asked his Mom to prepare his lunch box. He said he would be at the library, and wouldn’t be home until after supper. “For my case studies,” he lied. Instead, he went to the archives. The trip towards there seemed like a slow-motion segment of his life’s film. He could hear his footsteps, the buzzing of a fly and the brush of the wind on his cheeks. He would scour for microfilmed news items within a month or two from the date of his biological father’s “gruesome” death. As none came out from national dailies, he checked for microfilmed copies of local papers. Hungry and disgusted, Zac almost gave up when he spotted a tiny mention under the heading “murder or rightful defense among the folks of Dalanon?” “Dalanon?” Zac’s hair stood. He saw a small body of water, sensed the brush of cold air, and smelled the pungent sea sprays. And those strange gurgling noises. No wonder he felt a strong pull towards the village.

The incident was not covered in mainstream news, but in a tiny opinion corner of a local tabloid bannered “hard truths to stomach.” For the subject’s seriousness, the writing was light, irreverent even, interspersed with vernacular witticisms and popular moral teachings, such as “merisi,” meaning “bad deeds don’t pay.” The article, argued how village folks have the right to stump out criminality at their doorstep through self-help. It mentioned stealing fishnets goes beyond ordinary criminality as it turns upside down the very pot that provides food for families in the village. It then gave two thumbs up and “hurrahs” to the villagers’ acquittal.

Zac realized he was reading a rubber stamp commentary of a court decision dismissing the Dalanon murder case, in effect acquitting all the accused, for “lack of substantial evidence.” So, that was it? Zac sighed, strangely relieved to have gotten this far, though nagging questions remained. Neither the writer’s stand nor the court’s opinion bothered him. Zac’s analytical training assured him anyone could arrive at any kind of conclusion, depending on one’s ideological and emotional persuasion. As a law student, Zac was aware one could easily justify one’s conclusion, depending on which side one was on. What bothered him was the “accused’s acquittal” came by way and “courtesy of the pro bono services of Atty Frank Ziga,” his father.

IV

Dalanon was Zac’s only option. He broke down upon meeting his Aunt Lilia. “Why didn’t you tell me a murder happened in Dalanon?” Zac could hardly breathe as he whimpered, “Was my real father stoned?” Lilia herself trembled and could not answer coherently. “I’m sorry, Zac…really, really sorry. My brother made me swear not to say anything about the incident.”

“I understand Auntie, but please tell me. Was my real father a criminal? Am I the son of a bad man?”

“I will tell you everything, Zac. I want to take you to a place. But first we’ll pass by at your Nang Katang’s store. I’ll ask her to join us. She can better explain what happened.”

“This was where your father sat when he was stoned with these small rocks,” Katang pointed to a spot where a raised platform where folded fishnets used to be stacked. The place was a kilometer away from Dalanon village center, and near the boundary to the next village. “He sat under the raised platform the night he died as it was rainy. Some say he ate a late supper, and that he fed you, making sure you would not go hungry through the night,” Katang sighed. “The platform’s gone now,” she continued. “The village took it down after the incident. The village head thought it was a source of bad luck, a badge of shame for the place.” Zac looked closely at the spot where his father died. He saw himself there, a toddler, and barely out of babyhood, snugging in the arms of his elderly father. He noted the spot was at the end of a cove. Locals called the place a lake since the cove’s mouth was almost unseen. Around the still water were serrated mountain peaks, called “ngipon sa gabas” or “teeth of a saw” by villagers. Zac saw these in his dream.

“I know your father,” Katang volunteered. “He was an old and venerable man, known for his wisdom and power to heal. He was our shaman in my former village. People there would ask him for advice,” narrated Katang as she walked towards the sea.

“Did he tell you he was coming over to Dalanon?”

“No, he never told anyone. I recognized him when his dead body was paraded around the village – hogtied – “like a criminal,” to warn folks not to steal fishnets.”

“Did you believe them, Nang Katang?”

“Of course, I didn’t. Your real father was not a fisherman, so why would he steal fishnets? He was a respected man in our village with simple needs. I think he wanted to come – he willed to come here, in spite of his old age.”

“Did he know anyone in Dalanon?” Zac pleaded, already hard of breathing.

“As far as I know he only knows me and my late sister Muriela. It was your father who advised us to leave our village when our family was accused of witchcraft. He could have known I was living in Dalanon from my parents as they stayed behind in my former village.”

Katang, then with wide eyes, blurted, “I think your father wanted to take you to this place! Yes, yes, but is it possible? Knowing your father’s acumen, I think he knew he would die here. They said when he was stoned, he did not run, and just sat and prayed. He raised you high up with both his arms, asked blessings for you, mercy for his murderers, and then shouted, ‘Run, Atok, run!’”

Zac recalled his dream, as that was what his father said to him.

“Zac, there is something we wanted you to know,” his Aunt Lilia finally found the courage to speak. “Early in the morning the day your father died, one of the villagers took you to your Nang Katang’s store. He knew you would be safe there, and wouldn’t starve. But your Nang Katang had a better idea. We brought you to the Catholic nuns, and convinced your now father Frank to adopt you. That’s how you ended up with them. Your future with your father Frank could not have been brighter. Your Nang Katang and I think your real father foresaw this – he with his goodness and years of experience of helping people,” his aunt Lilia said, as she and Katang embraced Zac, with the warm hug of a mother.