In the main gate opens at 0500H. My smart sports watch reads 0438H. Emerging from the shadows of the mango trees fronting the women’s barracks, I walk briskly toward the lamppost. Silhouettes jog counterclockwise around the well-lit oval, their rhythmic strides breaking the pre-dawn stillness. I decide to join them.

Jogging at sunset is my choice of self-care, a ritual that keeps both body and mind in check. But last night, I missed it. I had just swapped my black leather pumps for running shoes when my boss, Colonel Mateo Dimalupig, hobbled into the office. His usual boyish grin was absent, replaced by an expression of quiet sorrow.

“Please look for this file.” He mumbled as he handed me a slip of paper. On it was a name:

PFC Percival Luna.

By the time I compiled the report and knocked on Sir Mateo’s door, it was past 1900H. He read it in silence, his face unreadable. At 1945H, his tall, broad-shouldered figure loomed over my desk.

“Keep this file, Grace,” he said, sliding the folder back to me. His voice was heavy, almost grieving. “Have a good night.”

I gave a jolly reply, but I doubted he heard me. I watched as him limp away, his left shoulder rising and falling with his uneven gait.

Sir Mateo carries the weight of battles long past. His weather-beaten face, battle-scarred body, and that permanent limp, all mementos of injuries untold. He was once a hero, a dauntless warrior who fought insurgents in Mindanao before joining a military mutiny that cost him his ascendant career. After three years in the stockade, he was granted unconditional amnesty. Now, desk duties and an anti-corruption unit were all that remained of his once-glorious service.

That night, I barely slept, my mind replaying Sir Mateo’s unusual request. By dawn, I decided a jog might clear my head.

The camp is eerily quiet, the solar-powered orb lamps casting a dim glow. I pass the empty car park behind the General Headquarters. Near the backdoor entrance, a dark figure moves. A granite statue brought to life? But no, it’s just the sentinel pouring coffee from a thermos.

I follow three joggers in white dry-fit shirts marked ARMY toward the Officer’s Clubhouse, deserted at this hour. Beyond it, the AFP Theater looms, its glass mosaic frontage reflecting a ghostly glow.

“Ghost of corruption,” Sir Mateo once scoffed, scowling at the structure. “That money should have gone to better barracks.” He rarely voiced such grievances, but that day, he did, grumbling about the security risks of having a public cultural center inside a military camp.

Beyond the theater is the Generals’ Quarters, a row of sprawling bungalows for star-ranked officers and colonels awaiting their stars, a stark contrast to the crumbling barracks where lower-ranking soldiers live. Last year, a fire gutted one of the houses. The flames were contained, but the rumors burned brighter: firefighters had allegedly found a briefcase stuffed with cash among the debris. The serial numbers were still intact.

Sir Mateo never commented on the incident, although he must have heard of it from the military grapevine.

Across from the Generals’ Quarters stands the Church, recently renovated. But the real wonder is its ceiling, a gradient of blue that darkened and lightened like the open sky. I later learned that it was an expensive wallpaper designed by an Air Force general, a fighter pilot who once soared through the skies.

I remind myself to tell Sir Mateo about it later. He has a habit of asking about the “goings-on” in my world—camp rumors, must-go staycations, fancy restaurants, encounters with the bizarre, and our all-time favorite, coupling and uncoupling in showbiz. I suspect it’s his way of keeping up with the other rumor-mongers.

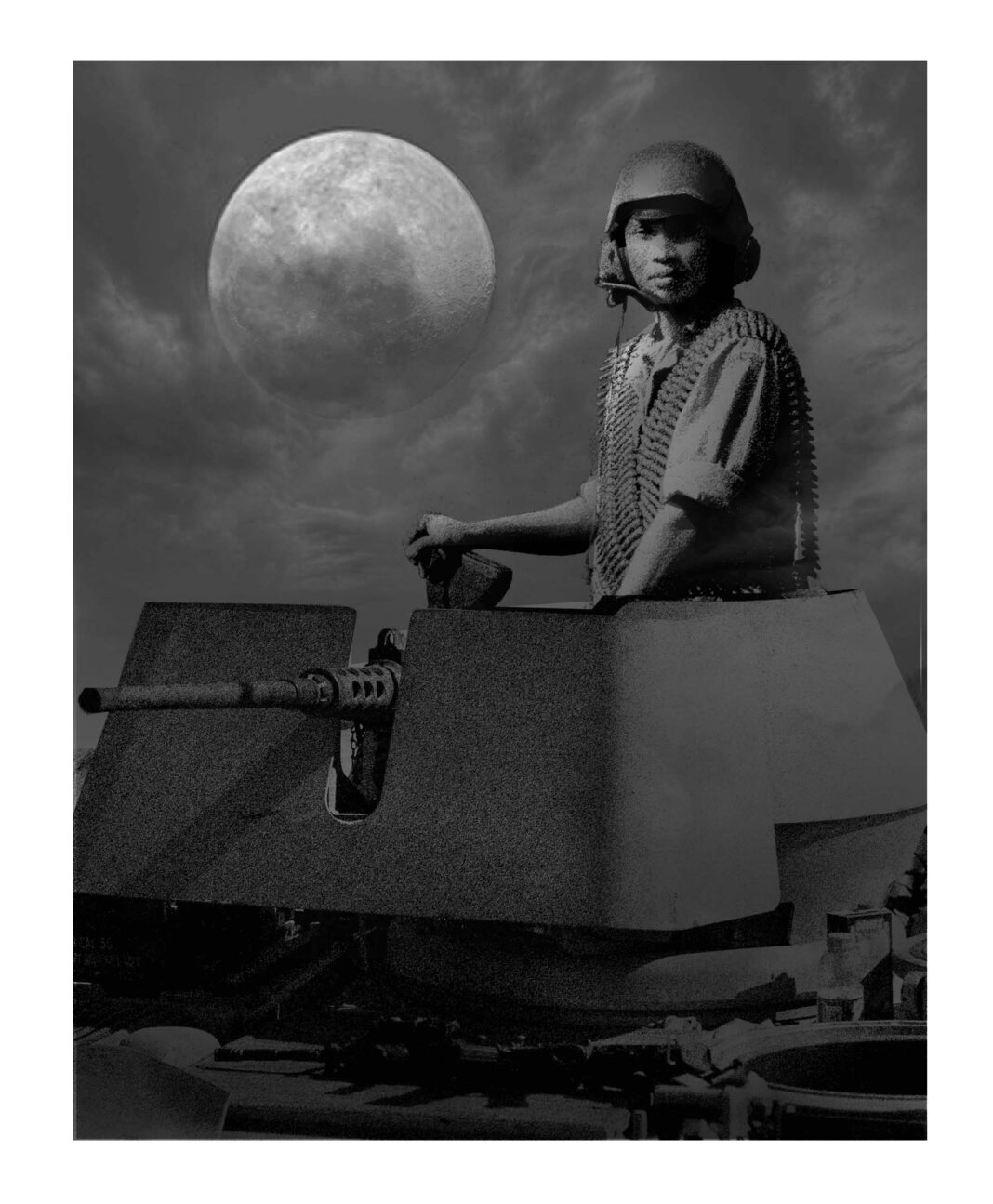

I slow down as I near the statue of General Emilio Aguinaldo, the camp’s namesake. Cast in bronze, the likeness of General Aguinaldo, the first President of the first Philippine Republic, sits astride a horse, sword raised, charging into battle. Slightly to his left, on the opposite side of the street, stands a rusting Armored Personnel Carrier (APC), its machine gun turret long disarmed, a relic of a failed coup.

I was a teenager living with my uncle’s family in Cubao when it happened. The ground shook. The sky lit up with volleys of cannon fire. My cousins and I huddled in the bathroom, but my uncle and older cousins watched from the rooftop.

Loyalist troops held the camp. My cousins swore that by dawn, bodies were piled as high as the fence at Gate 1.

The APC has been left where it was immobilized, its occupants killed or seriously wounded.

Then, movement.

A shadow flickers within the armored vehicle. I freeze.

A rustling sound breaks the silence, too strong for an early morning breeze. From the corner of my eye, I sense something, someone, shifting…My breath catches as a figure emerges, hesitant, then urgent. Someone scampers across the street, straight toward me.

“Hoy, ano ba!” I hiss, stepping back.

A soldier in a helmet and camouflage crouches in front of me, his hands trembling. His uniform is wet, though there’s no rain. Dark stains mar his collar. Caked grease smears his face. His hollowed cheeks and thin lips make him look barely out of his teens.

“The guardhouse is over there,” I snap, pointing toward the still-closed gate.

He stares at me wide-eyed. “You…you can see me?” His voice is hoarse, barely audible.

“Of course, I can see you!”

His breathing quickens. He cowers behind the monument’s base, eyes darting from the gate, grandstand, and the APC.

“Why are you hiding? Are you not the sentry?”

“No, Ma’am. I’m a gunner, Ma’am. I’m waiting for my CO.”

“Who is your CO?”

“Major Mateo Dimalupig, Ma’am. Fearless and brave, Ma’am.”

My stomach clenches. Sir Mateo?

“Wounded twice in Mindanao, Ma’am. He rescued his men under heavy fire,” he continues as if reciting a fact from memory. “My CO never leaves a man behind.”

“And your unit?”

“We came from Fort Bonifacio. My CO ordered us to move to Villamor Air Base. We crossed the South Expressway…took EDSA…turned right at White Plains. But Camp Aguinaldo was blocked. The enemy was strong, Ma’am.”

“Where are your mates? Where’s your gun?”

Silence. His fingers grip the edge of the concrete bench, knuckles pale. A white ribbon is tied around his upper arm.

“What is that?”

“Countersign, Ma’am. My CO placed it here last night. White for peace, he said. After this mission, there will be peace.”

He exhales, long and deep. His shoulders shake.

“I’ll get you some food,” I say quickly. “You must be hungry.”

He doesn’t respond.

Instead, he murmurs, “If you see Major Dimalupig, Ma’am, tell him PFC Luna ….”

Metal clatters against metal. The armored gate groans open as a convoy of military trucks rolls in, headlights flooding the street.

Blinded, I avert my gaze.

“Of course,” I reply, blinking fast.

But the bench is empty.

I spin around. No footprints. No sign of him. Only the armband remains, its knot still tied.

Written in black pentel ink: “PARA SA BAYAN.”

I glance once more at the APC.

Its side bears the words: “NUNQUAM ITERUM” — NEVER AGAIN.

A dark liquid snakes down from the turret, thick and sluggish. Blood? Oil? My insides turn as I take an uneasy step forward. A metallic scent wafts and lingers, stirring something primal—fear, dread, inevitable death. I sprint to get closer.

The dawn light plays tricks on my eyes, turning shadows into phantoms. For a moment, the viscous drip stops as if aware of my presence. A chill grips my spine.

Beneath the turret: 314 scrawled in red paint, dark and raw like an open wound.

A wisp of smoke curls in the air. I smell gunpowder. A cold breeze slaps my cheeks, waking me to the distant sound of boots shuffling, fading into the dying night.

A military truck rumbles past, headlights slicing across the dimness. The boom gate rises. A car slips through. The boom gate falls – like a guillotine. A faint glow blooms on the eastern horizon. Daybreak. I push forward, forcing my legs into motion, catching my pace in the morning twilight.

I feel cold. My palms are damp. I slide my hand into the pocket of my hoodie. My fingers brush against something smooth. And silky — like a white ribbon with a strange knot.