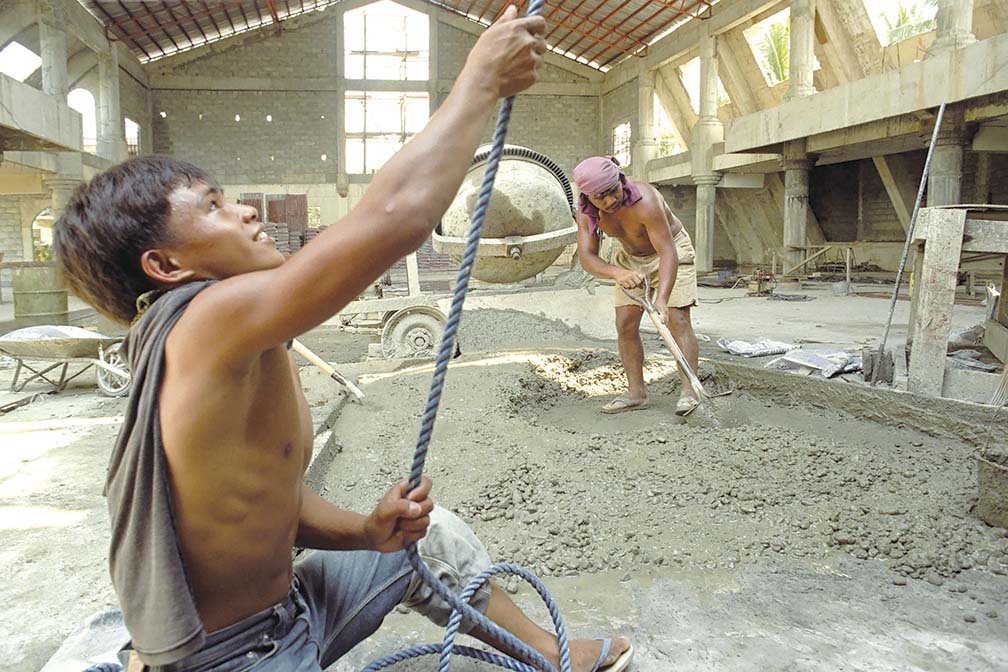

TOP PHOTO: Building workers. A young man, hoists a bucket of cement up during the rebuilding, renovation, of a building in Tabuk on the island of Luzon, province Kalinga. Construction is the top industry group affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. (Source: Dreamstime)

Between COVID-19 and the worsening economic situation in the country, organized labor is finding itself caught between a rock and a hard place.

Already, the number of organized labor in the Philippines is paltry compared to the total labor force. Some 45.2 million Filipinos make up the country’s labor force as of January 2021. Of these, only 10% are organized into trade unions and labor centers, roughly equivalent to 4.52 million workers.

Despite their being in the minority, organized labor—better known as workers organized into labor or trade unions—has been responsible for lobbying for workers’ rights and welfare since its first beginnings in the 1900s.

Intimidation, harassment, killings, prison, and anti–Communist propaganda have consistently stalked trade union work from the time of labor leader and founder of the old Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP) Crisanto Evangelista in the 1930s to the present Left to Right formations—Kilusang Mayo Uno, Federation of Free Workers (FFW), Trade Union Congress of the Philippines (TUCP), Bukluran ng Manggagawang Pilipino, Defend Job Philippines, National Union of Bank Employees, National Congress of Unions in the Sugar Industry, Alliance of Health Workers, Alliance of Concerned Teachers, BPO Industry Employees Network, COURAGE, Ugnayan ng Manggagawa sa Agrikultura, PISTON, Migrante, and Kilos na Manggagawa.

Still, the trade union movement in the Philippines progressed, in spite of these difficulties, on the strength of its capacity to organize and to consolidate its ranks to achieve specific labor demands—from wage increases and better working conditions to benefits accruing to agreed collective bargaining agreements (CBAs)

NEW NORMAL

In 2019, the deadly and rapid spread of the COVID–19 virus plunged the whole world into a pandemic and forced governments across the globe to adopt a new world order in social interaction.

This new norm severely tested labor’s capacity to organize and to push for economic and political demands.

The Labor Day rally this year saw Left–to–Right trade union formations calling for the resignation of Pres. Rodrigo Duterte. They announced over the media that they will mount the first face–to–face protest rally since the pandemic on the strength of some 10,000 workers who will join the rally.

Nagkaisa, a labor coalition of private and public sector unions and labor organizations, based its resignation call on “a ruined economy, massive destruction of jobs, rising prices of goods and services, inadequate aid, poor health response, intensified repression of trade union and human rights, endless disrespect of women, and surrender of the West Philippine Sea.”

Come May 1, a GMA7 online report pegged the number of individuals who participated in the rallies at 1,850, based on an interview with Philippine National Police (PNP) chief Debold Sinas.

About 10,366 police officers gathered on the roads leading to the rally sites to maintain health protocols, the GMA7 report said.

The Federation of Free Workers quoted a higher figure of 5,000 rallyists that gathered at Welcome Rotunda, instead of the Liwasang Bonifacio, as earlier announced.

Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU) and the Bukluran ng Manggagawang Pilipino (BMP) also held their protest activities at Welcome Rotunda.

PANDEMIC FEARS

A Jan. 2021 Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey showed that at least 91% of Filipinos worried over the possibilities that their immediate relatives would contract COVID–19.

Of the 91%, about 77% “worried a great deal” while 14% are “somewhat worried.” Some 3% worried a little while 5% are not worried at all.

The week before the May Day rallies, news about the runaway surge of COVID–19 in India resounded in media and social media. A sample of the headlines:

As COVID–19 Devastates India, Deaths Go Undercounted—New York Times

India coronavirus: Round–the–clock mass cremations—BBC News

India’s Seven–Day COVID Case Average Reaches 350,000, Deaths Triple in Last 21 Days—Newsweek

With the runaway surge of COVID–19 in India, Pres. Rodrigo Duterte once again emphasized to the public the need for safety protocols and for law enforcers to ensure that social distancing is observed.

On May 1, Health undersecretary Rosario Vergeire warned, in a report carried by CNN Philippines, that the Labor Day rallies can turn into COVID–19 super spreader events.

Vergeire added that the virus could spread in large gatherings, stressing the need for health protocols to be observed.

HUNGER, UNDEREMPLOYMENT

On this one day in a year when Filipino workers in their millions become a focus of media reports, organized labor made known their demands.

Julius Cainglet, vice–president of the Federation of Free Workers (FFW), said workers were the least provided for by the government during the COVID–19 pandemic.

“From the start of the lockdowns in March, government gave mixed signals that subverted workers’ chances of getting support from companies that employed them. There were Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) issuances that were released and later taken back, like Labor Advisory no. 17, series of 2020. At first, DOLE said employers may not give the minimum wage to workers during the pandemic. This gave license for many employers to bring down wages. But they took it back after labor unions lobbied for the enforcement of the minimum wage during the pandemic,” Cainglet said.

He added that DOLE also issued the extension of floating status of workers. “This promoted underemployment. What workers do not know is that if they resign while under floating status, their resignation will be voluntary. Their claim to separation or retrenchment pay and other benefits might be compromised. Unlike if they are outrightly fired, they can avail of separation or retrenchment pay, which they can use for their everyday needs or in looking for another job.”

Cainglet stressed that jeepney drivers hurt the most since many of them did not receive cash aid and were not part of the various support programs of the government. “Marami sa kanila napwersang mamalimos sa daan ng pagkain at pera. Mabuti na lang nagkaroon ng Community Pantry [Many of them were forced to beg in the streets for food and money. Good thing the Community Pantry came along].

According to a report of the International Labor Organization (ILO), more than 10.9 million Filipinos lost their jobs and had lower incomes and working hours in 2020, as the COVID–19 pandemic ravaged the economy.

“The impact of the crisis has been far–reaching, with underemployment surging as millions of workers are asked to reduce work hours or no hours at all,” the ILO said.

GOVERNMENT ADMITS

More than a year after the first lockdown in March 2020, the government is still the first to consistently admit that it has not resolved the hunger and unemployment affecting the poor in the country.

Pres. Duterte consistently stressed that the ravaging effects of the COVID–19 pandemic are the reasons for these persistent health and economic problems.

In its Nov. 3 to Dec. 3, 2020 Rapid Nutrition Assessment Survey, the Department of Science and Technology–Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST–FNRI) reported that 62.1% of Filipino families have experienced moderate to severe food insecurity.

The DOST–FNRI survey indicated that around 71.7% of Filipino households have purchased food on credit, 66.3% have asked for food from relatives or neighbors, 30.2% have resorted to barter, and 21.1% have limited their food intake in favor of children.

Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque acknowledged that much more needs to be done to fight hunger, adding that government is easing quarantine protocols to allow more Filipinos to return to work for them to earn money while the country is still grappling with the COVID–19 pandemic.

National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) Secretary Karl Kendrick Chua bared during the April 19 Talk to the People of Pres. Duterte that from February to March 2021, food inflation climbed to 6%, from only 2.7% in 2020.

“In summary, Mr. President, we are in a COVID crisis right now. We cannot afford that the people will have both an income problem and a price problem,” Chua said.

He added that this was the reason why NEDA supported the temporary bringing down of the tariff on pork to 5% for the first three months and 10% thereafter for a period of one year. “The plan is to bring down the inflation rate to 3.8%.”

An April 2021 economic bulletin released by the Department of Finance (DoF) placed the unemployment rate at 8.8% in February. This translated to 4.18 million out–of–work Filipinos compared to 3.95 million in January.

In like manner, during the same period, the DoF said that underemployment affected 7.85 million Filipinos, up to 18.2% in February from 16% in January.

Overall, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported a 10.1% economic contraction in the National Capital Region in 2020, stating that it was the worst ever recorded since the agency began its regional series in 2000

The PSA attributed the dismal 2020 economic performance to the prolonged quarantine restrictions—which dampened business and consumer confidence.

COMPANY CLOSURES

The sharp increase in the number of the unemployed and underemployed could be partly explained by widespread company closures, mostly involving small and medium scale enterprises.

Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) figures showed that during the first year of the pandemic lockdowns, around 26,060 establishments reported the implementation of retrenchment and permanent closure from January to December 2020, with roughly 428,701 workers affected.

For the first three months of 2021 alone, some 4,285 establishments reported retrenchment and permanent closure from January to March or roughly 118,307 affected workers.

FFW President and lawyer Sonny Matula said that the lack of travel options like jeepneys and other less expensive forms of travel like tricycles restricted the movement of workers. “It increased their transportation expenses, since not all companies provide shuttle service.

OFWs

In his April 19 report to the President, DOLE Secretary Silvestre Bello III said that as of 2020, some 8,874,472 Filipinos lived and worked overseas. Of these, about 3,497,261 were documented, while an estimated 1,580,684 were undocumented workers.

Bello reported that 19% of the 3,497,261 were displaced because of COVID–19 or roughly 647,827 Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs). These workers either lost their jobs or were prevented from reporting for work, thereby not being able to earn a living.

Of the 647,827 displaced OFWs, the DOLE was able to repatriate 519,566, using P5 billion from the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA).

The Labor secretary further said that the remaining, about 49,000, are still in the process of repatriation.

FFW’s Cainglet said that distressed OFWs would call their office to inquire about possible “ayuda” or cash aid. “We are calling for a P10,000 support for those who lost their jobs and an P8,000 wage subsidy for those who kept their jobs but were forced only to report for work once or twice a week.

“For Nagkaisa, we are batting for employment generation and cash aid, especially in these times when there are no jobs or work is reduced because of the pandemic,” he said.

Cainglet also added that there are many situations when workers were not able to avail of “ayuda” or cash aid because their companies did not comply with their Social Security Service (SSS) requirements. “Other companies had such meager operations, they were not registered (in the SSS).”

KMU, for its part, called for a daily wage subsidy of P100 for all workers, a P10,000 cash aid for displaced workers and vulnerable sectors, and a P15,000 production subsidy for farmers, as well as a wage subsidy for workers in the micro, small and medium enterprises sector.

PANDEMIC BILLIONAIRES

In the face of prolonged extreme want characterized by loss of jobs, company closures, and hunger for millions of Filipinos, some companies and individuals experienced global windfall revenues despite the pandemic.

Businesses relating to food manufacturing, food delivery service, groceries and supermarkets, and broadband service, registered a profit and generated jobs for many displaced workers.

Online delivery service foodpanda Philippines reached an estimated 70% market share among food delivery mobile apps in the country after demand surged last year.

Aboitiz Equity Ventures reported a huge jump in earnings for the first three months of 2021. The achieved a consolidated net income of ₱7.6 billion for the first quarter of the year, a significant increase from the ₱2 billion it reported during the same period a year ago.

CNN Philippines reported that some 17 Filipinos made it to Forbes World’s Billionaires List for 2021, an increase of two Filipino billionaires from 2020’s 15 listed billionaires.

Making it to the top of the list is former lawmaker and real estate magnate Manny Villar ($7.2 billion or around ₱349.7 billion), followed by Ports tycoon Enrique Razon Jr. ($5 billion or around ₱242.8 billion), LT group founder and businessman Lucio Tan ($3.3 billion or about ₱150.2 billion), Andrew Tan of Alliance Global Group ($3 billion or about ₱145.7 billion), the Sy siblings—Hans and Herbert Sy ($3 billion or around ₱145.7 billion each); Harley, Henry Jr. and Teresita Sy–Coson ($2.7 billion or about ₱131.1 billion each), and Elizabeth Sy ($2.4 billion or around ₱116.5 billion.

Also in the 2021 Forbes list are: Jollibee founder Tony Tan Caktiong and his family ($2.4 billion or around ₱116.5 billion), San Miguel president and chief operating officer Ramon Ang ($2.2 billion or about ₱106.8 billion), Businessman Inigo Zobel ($1.4 billion or around ₱68 billion), JG Summit Holdings leader Lance Gokongwei and Roberto Ongpin ($1.2 billion or about ₱58.2 billion each), Century Pacific founder Ricardo Po Sr. and family and DoubleDragon Properties chairman and Mang Inasal founder Edgar “Injap” Sia II ($1.1 billion or about ₱53.4 billion each).

As reported by CNN Philippines, “a new billionaire is minted every 17 hours on average over the past year.” According to Forbes, “the globe’s richest individuals are $5 trillion wealthier this year than they were in 2020.”

BIG & SMALL CHARITY

At the start of the pandemic, big business quickly came forward and extended help.

The Aboitiz Group, along with over 30 private companies, partnered with the Philippine government and British drugmaker AstraZeneca to procure 2.6 million COVID–19 vaccine doses, as part of the government’s ongoing pandemic response.

Aboitiz Foundation President and Chief Operating Officer Maribeth L. Marasigan and 30 other company heads and representatives signed the deal in a virtual ceremony last Nov. 27, joining Galvez, Presidential Adviser for Entrepreneurship and Go Negosyo founder Joey A. Concepcion, and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals Philippines, Inc. president Lotis Ramin.

About 300 companies, and 39 local government units have signed a tripartite agreement to secure 17 million doses of vaccines from British drugmaker AstraZeneca.

SM Foundation donated over PHP400 million in essential medical supplies and equipment and reached out to marginalized sectors most affected economically.

It likewise donated PHP100 million through Project Ugnayan of the private sector and Caritas of the Catholic Church to urban poor families impacted by the lockdown were likewise donated by SM.

“This social good effort is part of the earlier announced PHP100 million support of the SM Group, through SM Foundation that will be given to government hospitals and other medical institutions. Other initiatives of the SM Group in response to this crisis are the waived rentals of all tenants of SM Supermalls nationwide, continued compensation of their employees, and the extension of an Emergency Financial Assistance to its front liners, security guards and janitorial staff during the Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) period. SM also partnered with Goldilocks recently to bring cakes and other pastry products to COVID–19 frontliners,” SM Foundation said in a statement.

BDO Foundation donated 300 smartphones with prepaid loads and 550 power banks to the Department of Science and Technology (DOST). The items were turned over by BDO Foundation president Mario Deriquito to DOST National Capital Region regional director Jose Patalinjug III.

BDO Foundation launched the fund–raising activity Peso–for–Peso Donation Drive. Proceeds were used to provide test kits and supplies to COVID–19 testing centers in underserved communities nationwide.

Towards the third week of April, Metro Manila woke up to the sight of the Community Pantry, which allowed poor folks to donate and get food for free.

Started in Maginhawa, Street in Quezon City, the community pantry serviced mostly the urban poor communities in Quezon City.

Overnight, the community pantries mushroomed in Metro Manila and in the provinces of Rizal, Laguna, Quezon, and even in some areas in Mindanao.

“Community pantries are a big help because it promotes solidarity,” Cainglet said. “There is a means for people to share meaningfully with others. I think it is also a political message that people are fed up with incompetence, the prioritizing of military solutions, instead of meaningful economic solutions.”

It seems, however, that the positive mantra generated by community pantries was dampened by the troubled birthday community pantry organized by actress Angel Locsin that saw a 67–year–old balut vendor die from the onrush of thousands who trooped to the pantry held in Barangay Holy Spirit.

A week later, Quezon City officials, led by Mayor Joy Belmonte urged those who went to the Locsin community pantry to get tested for the COVID–19 virus.

GLOBAL CALL

Around the world, worker rallies reverberated with calls for labor protection, lower rents, higher wages, more jobs, and promotion of workers’ rights amid a pandemic that has turned economies and workplaces upside down.

In countries like France and Germany, the annual celebration of workers’ rights produced a rare sight during the pandemic: large and closely packed crowds, with marchers striding shoulder–to–shoulder with clenched fists behind banners.

In Germany, where previous May Day demonstrations have often turned violent, police deployed thousands of officers and warned that rallies would be halted if marchers failed to follow coronavirus restrictions. Protests in Berlin called for lower rents, higher wages and voiced other concerns.

Some demonstrations, constricted by coronavirus restrictions, were markedly less well–attended than those before the pandemic. Russia saw just a fraction of its usual May Day activities amid a coronavirus ban on gatherings. The Russian Communist Party drew only a few hundred people to lay wreaths in Moscow. For a second straight year in Italy, May Day passed without the usual large marches and rock concerts.

As it was in the Philippines, cops in Turkey prevented the May Day protests, enforcing virus lockdowns and making hundreds of arrests.

In Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy, thousands voiced anger at a new jobs law that critics fear will reduce severance pay, lessen restrictions for foreign workers and increase outsourcing as the nation seeks to attract more investment. Protesters in the capital of Jakarta laid mock graves on the street to symbolize hopelessness and marches were being held in some 200 cities.

In Italy, police faced off against a few hundred demonstrators in the northern city of Turin. In Rome, Italy’s head of state paid tribute to workers and health care workers.

“Particularly heavy has been the impact from the crisis on female labor and on the access of young people to jobs,’’ Italian President Sergio Mattarella said.

Across the Atlantic in Brazil, thousands of demonstrators backing President Jair Bolsonaro’s anti–lockdown stance rallied at Rio de Janeiro’s iconic Copacabana beach—one of several such gatherings across the country.

Bolsonaro’s office said he flew in a helicopter over a similar rally in the capital, Brasilia, where some demonstrators carried banners urging him to call in the military. There were also protests in Brasilia and other cities against Bolsonaro’s handling of the pandemic. Brazil has seen over 400,000 confirmed COVID–19 deaths, a toll second only to the United States.

TOUGH CHOICES

In the Philippines today, there are two narratives. One believes in Pres. Duterte and his administration. The other blames the President and his government for all the harsh conditions in the face of the COVID–19 pandemic.

Organized labor has made it plain that Pres. Duterte should resign. In numbers, they account for 4.52 million individuals out of 45.2 million that comprise the labor force.

Last May 28, a survey conducted by Social Weather Stations (SWS) revealed that 79% of Filipino adults believe that violators of minimum health protocols are the “real cause” of the current spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in the country.

The situation today is that Filipinos fear the COVID–19 pandemic. It is, perhaps, one of the reasons why it is taking longer to reopen the economy as the average Filipino prefers to stay at home, rather than go out.

To have numbers that can translate to a “critical mass,” trade unions will have to reach out and connect with the millions of unorganized workers.

But how does one do this in the face of the COVID–19 pandemic?

FFW President and lawyer Sonny Matula has this to say: “Despite the dire situation, the workers will continue to act and fight. Given the ongoing struggle, we only want to ensure the safety of the workers and a better future for the working class and the entire nation.”—with reports from AP reporters NICHOLAS GARRIGA, NINIEK KARMINI and JOHN LEICESTER