(Elections stand as the chief reforming mechanism in a democracy. How well has the Philippines fared in the parade of Presidents elected from the time of Emilio Aguinaldo to Rodrigo Roa Duterte?

At 96, National Artist for Literature F. Sionil Jose ponders on this question as he writes for the Philippines Graphic a singular essay, with the authority and wisdom of one who has witnessed and lived through 16 Presidents.—Ed.)

This is a personal essay, my impressions on our politics and the presidency as I have observed both from my teenage years onwards. In this my twilight, I am now 96, with memory still keen, I try to locate our country in the wider context of Asia’s past.

My conclusions are not final. They may even be questionable. But there is one conclusion I hold on to: all our leaders are failures. Whereas other countries with comparable problems had modernized, we were left behind. I’ll attempt to explain why.

First and foremost, all of them were hobbled by their own egos, their personal agendas, ethnicity and their loyalty to friends, and family. It was only Magsaysay who was truly selfless, but alas, on the second year of his term, he was killed in that plane crash in Cebu. Marcos—the most brilliant of them all, started with so much promise but in the end, ego and greed destroyed him.

Old fashioned presidents like Osmeña and Quirino were too conservative, too mired in their own pasts to understand the need for radical solutions. Indeed, our leaders were ill equipped to face the massive changes after World War II—the problem of rehabilitation with a new power elite, the rapid population growth, and the scientific changes that affected industry, communications and globalization.

Those who were smart enough to have read the future and take advantage of the opportunities flourished—the Chinese magnates all of whom started banks—but being heirs to the imperial order, they became the domestic exploiters of the country.

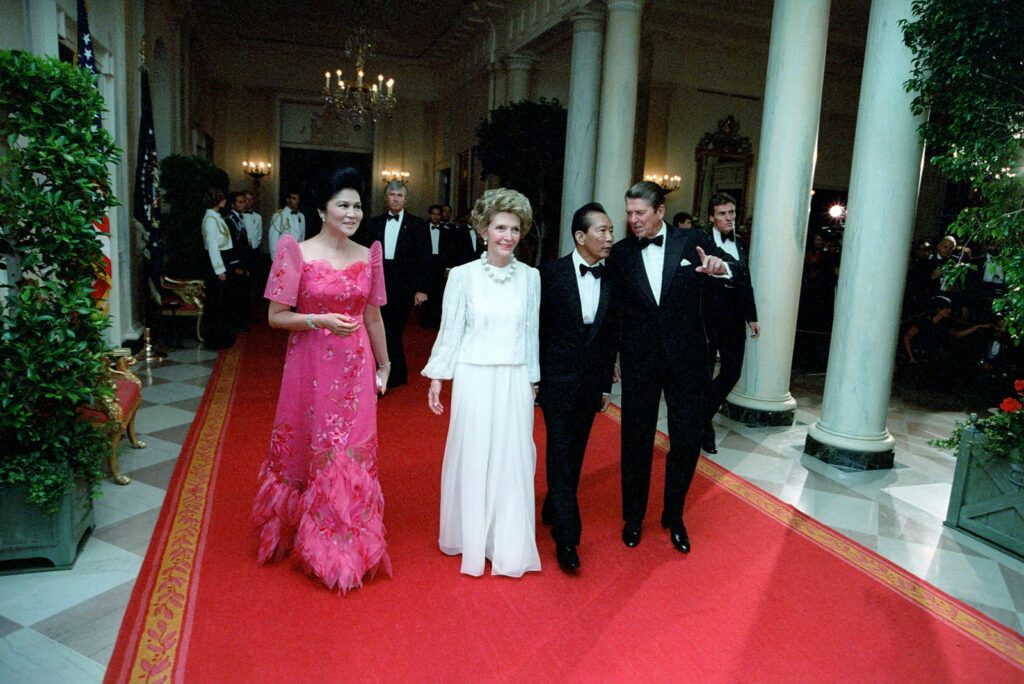

In this presentation, in some instances, I have focused on the wives of our Presidents. They are after all, the first influencer of their husbands. Some—bless them, like Mrs. Ramon Magsaysay did that unobtrusively, keeping themselves almost anonymous. One, like Imelda Marcos, flaunted her status for which she was both adored and scorned. Mrs. Ming Ramos, too, kept herself in the background even while she did civic work.

EMILIO AGUINALDO (1899-1901)

In 1935 an election was held for President of the Commonwealth—the government set up by an agreement between the United States and the Philippines in preparation for the American grant of Independence after 10 years.

I was in Grade Five but I remember very well that Manuel Quezon, Emilio Aguinaldo and Gregorio Aglipay ran for President and Quezon won. I was to encounter in our Grade Six history class the Pact of Biak-na-Bato which marked the end of the first phase of the Revolution started by Andres Bonifacio in 1896. General Emilio Aguinaldo was the beneficiary of that agreement.

I met him finally in 1950 when as staff member of the Manila Times Sunday Magazine, I went to Kawit, Cavite to interview him. At the time, I was doing research for my novel, Po-on, the first in terms of chronology of my five-novel Rosales saga. The novel is set on the waning days of the Spanish regime and the onset of the American Occupation. It ends with the Battle of Tirad Pass. I had of course wanted to know more about Bonifacio’s death about which I had already read that Aguinaldo willed it. Aguinaldo was in his eighties, with white hair and watery eyes. He was very soft-spoken and emphasized carefully what he said, punctuating each pause with a polite “opo.” He must have anticipated my question which I didn’t ask directly, intimidated as I was by his very polite manner. He said, “In a revolution there must only be one leader.”

He recounted his flight across the Cordilleras and the Sierra Madre to the Pacific coastal town of Palanan where, betrayed by the Macabebes, the Americans captured him and effectively ended the Philippine-American war.

The rift in the Katipunan was already obvious before its founder was killed. Aguinaldo was a rich Cavite landlord. Bonifacio, though possessed with education, was a clerk from the masa. This social divide pervaded the Malolos government led by Aguinaldo. He allied himself with the rich Manila principalia—the Legardas, Aranetas, and Pedro Paterno as against Apolinario Mabini, the poor lawyer from Tanauan, Batangas. Aguinaldo asked to join the cabinet but later was eased out. The Americans had occupied Manila.

In the daytime, the wealthy ilustrados were in Malolos but at night, they were in Manila negotiating with the Americans, proposing an American state for the Philippines under their Federalista Party.

In the treaty of Paris signed by Spanish and American representatives in December 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. The American acquisition of the Philippines was opposed by many Americans. The American tycoon, Andrew Carnegie wanted to return the $20 million and writers like Mark Twain and the poet Robert Frost himself told me he opposed America’s annexation of the Philippines. It was inevitable for the Philippine-American war to break out. Aguinaldo’s ragtag army was no match for the large, well equipped invasion force. In an epic retreat, he fled to Palanan on the Pacific coast.

I visited this isolated coastal town in the 1950s. I went there on a Navy patrol ship. The town had no pier. It was really small, with the usual Catholic church and municipio. I wonder how the town looks now.

Aguinaldo’s capture in Palanan ended the Malolos Republic—the first in Asia. Aguinaldo was accused of masterminding the assassination of Antonio Luna, too, and of how he spent the money from the Pact of Biak-na-Bato. All these considered, Aguinaldo still stands out as an authentic hero. Faced with superior forces and betrayed by his own people, he fought and lost.

A major issue that has troubled the Filipino people from the Spanish regime onwards is independence, not so much as a political fact but as an economic condition. Poverty was not so evident in the early days of this nation. But this was simply because the population was still very small, not even 20 million when the First Republic was proclaimed. But as the years went on, the question of property and poverty became entwined.

The Americans surely recognized this, the inequitable distribution of land under the Spanish regime, for which reason, almost immediately at the start of the colonization, they established the Torrens system of ownership. In a vast cadastral survey of the country, the lands that were already titled were identified. By that time, many farmers had already cleared so many sections of the country that were forested but they had no titles or “mojon” markers.

Mostly illiterate, the boundaries of the lands they cleared were trees, creeks, mounds. The educated Filipinos took advantage of the cadastral system and obtained titles of many of the lands cleared by the settlers. Overnight the small independent farmers became tenants. Early enough, the agrarian problem was exacerbated by the harsh conditions imposed by landlords. Agrarian repression turned violent. Peasant revolts occurred sporadically during the Spanish regime, many of them the result of oppression imposed by the friar landlords. Here, the case of Rizal’s family who were dispossessed in Laguna by the friars is a notable example. The Colorum revolt in Pangasinan in 1931, the Sakdal uprising in 1935 in Central Luzon, and the Hukbalahap uprising in 1949-1953 were all agrarian in origin.

The NPA rebellion that this government has yet to suppress is spawned primarily by poverty.

Taiwan and Japan had sweeping, successful agrarian change within the last two generations and is responsible for the economic development in these countries but much more significant is its enhancement of mobility for the very poor.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who initiated this sweeping agrarian reform in Japan, knew agrarian conditions were similar in the Philippines. Why didn’t he do it in the Philippines when it was possible for him to do so during the Liberation? Simple—many of the big landlords were his personal friends. Indeed, American colonialism was truly compadre colonialism. And so, to this very day, poverty and the agrarian problem persist but the old solutions are no longer valid. It is necessary now to maximize agricultural production for there is but little land that can be distributed under the sweeping redistribution that took place with the Marcoses land reform decree. Land grabbing is now the problem this government must resolve.

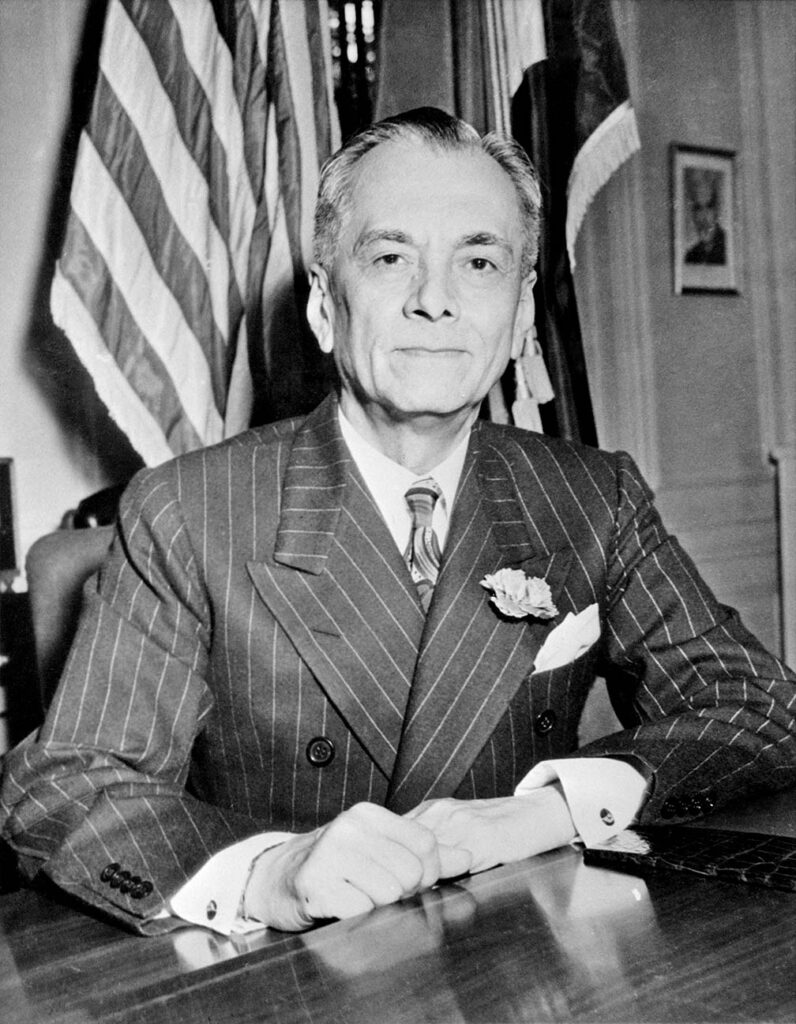

MANUEL L. QUEZON (1935-1944)

Manuel L. Quezon was our playboy President whose libido was heightened by tuberculosis. This was what was gossiped about in 1938 when I came to Manila. And why not? Quezon was handsome, dapper and a powerful orator.

I always attended the November 15 Commonwealth parade at the Luneta. It was dominated by Quezon delivering his usual fiery address.

His only son, Manolo, was a friend. I met him at the University of Santo Tomas where he was then a Dominican novice, and I was on the staff of the university paper. I also knew Serapio Canceran, Quezon’s private secretary from Cagayan. From both, I was able to form a dear image of Quezon, the man.

He was born in August 19, 1878 in the Pacific coastal town of Baler, Tayabas. He was a veteran of the Philippine-American war, as aide de camp to General Emilio Aguinaldo. After Aguinaldo’s surrender to the Americans, he continued his law studies at Santo Tomas, passed the bar and joined the government service. He was elected governor of Tayabas province in 1906 and the following year, as representative of the National Assembly.

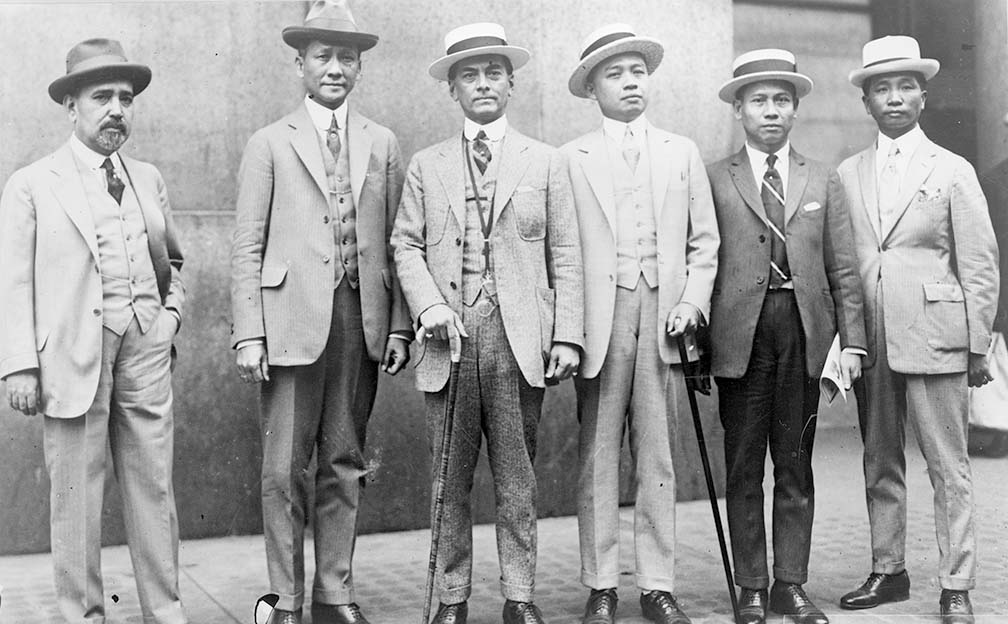

As Congressman, Quezon was very active in the independence movement. Elected to the Senate, he headed the first Independence Mission to the US Congress in 1919. In 1935 he won the Presidency as Nacionalista Party candidate. Incidentally, in these Independence Missions, he detoured to California. The late Carlos P. Romulo told me he dated Marlene Dietrich and Greer Garson.

By this time, Japan’s imperial intentions began to alarm the United States. Quezon, following American moves, decided to develop the country’s defense capability. He asked MacArthur to come to Manila to set up an Army.

Quezon attended to the agrarian problem that was seething. In 1935, the Sakdal peasant rebellion had erupted in Central Luzon. Congress passed a Tenancy Law that was flawed. He initiated the opening of Mindanao to settlers.

Quezon was very partial to his ethnic origins. He made Tagalog the National language. He was also partial to his friends. He created Quezon City as the national capital and gave choice portions of it to his mestizo friends.

As for Baler, his hometown, when I visited it in the 1950s, it seemed as if for the town, time had stopped. Quezon did nothing for it, ensconced as he was in Manila, playing poker and chasing pretty women. It was former Senator Edgardo Angara who made Baler the booming tourist destination it is today.

Quezon married his cousin, Aurora Aragon who was killed by the Huks in a mistaken ambush in Bongabon, Nueva Ecija in 1947 together with daughter Baby and her husband, Felipe Buencamino. Quezon was compassionate; he opened the country to a thousand Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Germany.

Quezon did not see the Philippines liberated by his friend General MacArthur. When the war with Japan started, he was evacuated to Corregidor then to Australia onwards to the United States where he formed a government in exile. His tuberculosis worsened and on Aug. 1, 1944, he died in Saranac Lake, New York. His body was brought back to Manila by former US High Commissioner Frank Murphy and is now at the Quezon Memorial Shrine in Quezon City.

I saw only one of Quezon’s girlfriends, Amparo Karagdag. She was petite, beautiful, a movie star. They were shooting a scene before the Manila Hotel. Early enough, I had started gathering bits and bits about the affairs of our Presidents but I gave it up when I found it too messy. For all his extravagances and picadillos, Quezon towered over all the politicians in his time, and was adored by his countrymen.

He left us some memorable quotes: “Better a government run like hell by Filipinos than a government run like heaven by Americans.” Quezon was also a prophet.

JOSE P. LAUREL (1943-1945)

During the Philippine Revolution of 1896, some thinking Filipinos already considered Japan a friend and champion. This was a good 45 years before Japan attacked the United States Naval base in Hawaii on Dec. 8, 1941.

Japan did send arms and even officers to train the Philippine revolutionary army. The ship carrying the arms capsized in bad weather and the officers-teachers returned to Japan due to the language problem. They could not communicate with the revolutionaries, though they were facile in Spanish.

When Japan invaded the Philippines just 10 hours before they attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, President Quezon ordered Jose P. Laurel, Jorge B. Vargas and other Cabinet officials to stay.

The Laurels of Batangas are known for their ties with the Japanese. Born in Tanauan, Batangas on Mar. 9, 1891, Laurel had sent a son to study at the Imperial Military Academy in Tokyo.

Laurel restudied law at the University of the Philippines under George A. Malcolm whom he succeeded as Chief Justice. Like several prominent Filipino lawyers, he got his L.S. Degree from Yale. In February 1936, he was appointed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court and as such, penned several important decisions, among them, the definition of the limits of government.

Laurel was a rigid nationalist and advocate of social justice—all these were emphasized in his court decisions.

In 1943, the puppet National Assembly elected him President. He couldn’t have done much. That year, the country was plagued with shortages. Japanese brutality had angered Filipinos and all over the country guerrillas had proliferated. Laurel was able to resist the Japanese pressure for him to declare war on the United States. Meanwhile, right in Manila, the guerrilla movement grew. Laurel was shot while playing golf at Wack-Wack. Fortunately, he survived.

Towards the end of the war, Laurel fled to Baguio with the Japanese and before the city fell, he escaped to Aparri and from there, on a Japanese plane, he flew to Japan. When the Americans occupied Japan, he was put in prison. Returned to Manila, he was accused of treason but was never jailed because President Elpidio Quirino proclaimed amnesty to all those who collaborated with the Japanese.

Claro M. Recto, however, was jailed in Iwahig. This made him very bitter. In an interview, he told me that Manuel Roxas collaborated with the Japanese more than him. He did not appreciate that MacArthur and Roxas were good friends.

Laurel returned to the Senate in 1951, garnering the most number of votes. President Magsaysay appointed him the head of a mission to the United States to negotiate trade and other issues. The result is the Laurel-Langley Agreement.

In his retirement, his efforts were directed toward the development of the Lyceum of the Philippines, the university in Intramuros which the Laurel family owns. Laurel died of a heart attack in 1959.

To this very day, he and all those who collaborated with the Japanese are cocooned in doubt. Those of us who survived Japanese brutality will always consider the collaborators as traitors even if we may have forgiven them. Collaboration with the Japanese may have been politically resolved, but as a moral issue, it continues to fester.

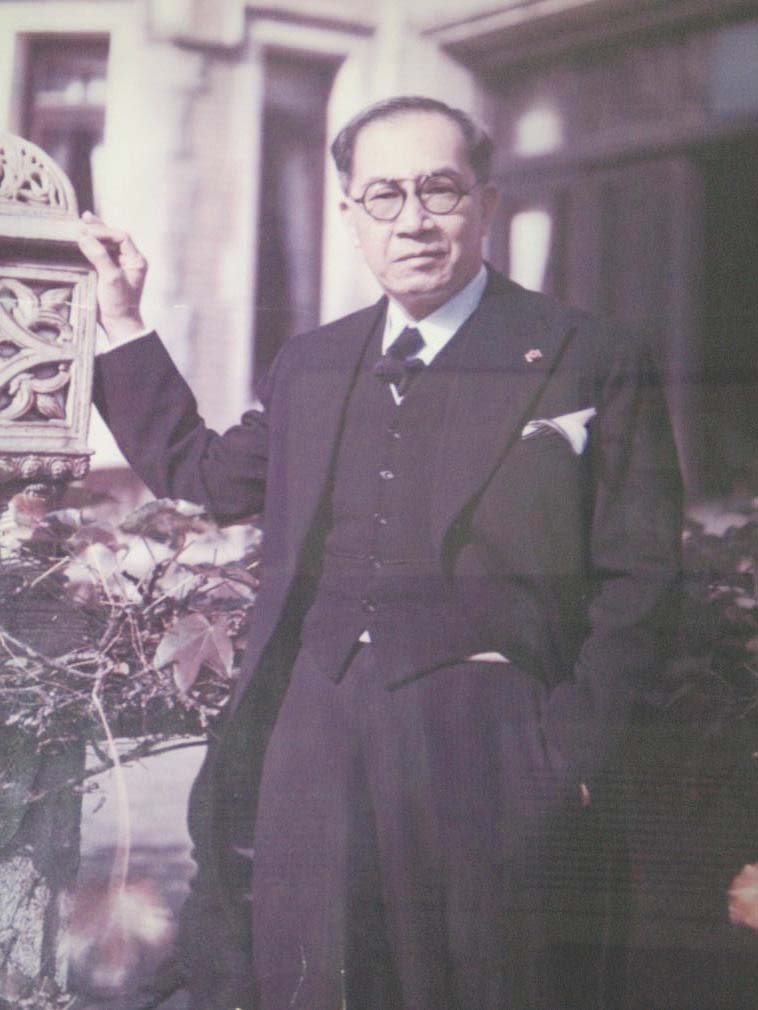

SERGIO OSMEñA (1944-1946)

Sergio Osmeña Sr., like Manuel L. Quezon, was a veteran of the Philippine Revolution. He served as courier and journalist on the staff of General Aguinaldo. He was born illegitimate to a wealthy Cebu family on Sept. 9, 1878. His mother Juana Osmeña y Suico never married his father. Osmeña was Quezon’s Vice President, a founder of the Nacionalista Party and the first Visayan to be President.

The Osmeña family, Cebu’s most powerful, includes his son, former Senator Sergio Osmeña, Jr.; former Senators Sergio III, and John Henry Osmeña; former Cebu governor Lito Osmeña, and former Cebu City Mayor Tomas Osmeña.

Sergio Osmeña, Sr. went to San Juan de Letran College in Manila where his classmates were Manuel Quezon, Juan Sumulong and Emilio Jacinto. He took up law at the University of Santo Tomas. He was elected Cebu governor in 1906 and representative to the First National Assembly in 1907, where he was elected Speaker. Osmeña was only 29 years old.

For a time, there was intense rivalry between him and Quezon but eventually, they joined hands to fortify the Nacionalista Party which was now confronted by the growing Democrat Party.

In that 1935 election that established the Commonwealth, Quezon was President and Osmeña was his Vice. When Quezon died in 1944, Osmeña was sworn in as President by Justice Robert Jackson in Washington. He returned to the country with General MacArthur in October 1944.

Upon the liberation of Manila in Feb. 27, 1945, in a ceremony at Malacañan, Osmeña thanked the United States for liberating the Philippines. MacArthur announced the restoration of the Commonwealth. There was a lot of work to be done, the organization of government, rehabilitation, rebuilding the Philippine National Bank.

Senator Manuel Roxas and Elpidio Quirino called for an election and President Osmeña agreed and that election was held in April 1946. In the 1946 election, President Osmeña refused to campaign, saying he stood by his record of service.

He was very honest as were many of the civil servants at the time, reared as they were in the finest traditions of the First Republic. But some of the Osmeñas who followed him are held in doubt.

Roxas won and Quirino was his Vice. No charges of corruption tainted Osmeña’s brief presidency. He retired to his home in Cebu. He died of pneumonia at 83 on Oct. 19, 1961. He was buried at the Manila North Cemetery.

America, America: From Roxas onwards

Another major issue that our Presidents had to face was our relationship with the United States, the American dominance over our economy and culture. With colonization and exploitation, the United States created the Filipino oligarchy as its ally. And the Filipinos gladly accepted this domination, enforced by gratitude for our liberation from Japan.

Former Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos was right in initially distancing himself from the United States, but was wrong in initiating the emasculation and then the removal of the American bases. They were not obstructions to our development. Look at Japan—the Japanese pay for the United States bases there.

Cory Aquino realizing this tried very hard to see to it that the bases remained but 12 hyper nationalists in the Senate voted them out. I wonder if China would bully us if the bases were still here.

President Duterte is correct in opening up this country to closer relations with China and Russia. But he over did himself with China and the developing China which needs raw materials and breathing space. I do not know how far China will go insofar as dominating our region.

Our Presidents in the past had never really been concerned with China. It was Marcos who began that relationship and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, and finally, Duterte, who strengthened it.

It was Noynoy, however, who stood his ground and brought our Chinese problem—China’s occupation of our Scarborough shoal— to the International Court of Justice. And with former Justice Antonio Carpio’s staunch defense, we won.

MANUEL A. ROXAS (1946-1948)

Born on January 1, 1892, Manuel Acuña Roxas became the first President of the Third Republic after the United States granted full independence to its only colony. He was the youngest governor of Capiz from 1919 to 1922.

In 1921, he married Bulacan beauty queen, Trinidad de Leon. His son, Gerry, later became a Senator.

Elected to the House of Representatives in 1922, Roxas was House Speaker for 12 years, then Secretary of Finance. He was Brigadier General in the Army organized by General MacArthur and a guerrilla during the Japanese Occupation.

When Quezon left for the United States, Roxas went to Mindanao where the Japanese captured him. He returned to Manila to be adviser to President Laurel.

In 1945, when Congress was convened after Liberation, Roxas was elected President of the Senate. He left the Nacionalista Party and formed the Liberal Party. Roxas had MacArthur’s backing. He was the last President of the Commonwealth.

Roxas became President of the Third Republic from 1946 to 1948. A massive audience witnessed his inauguration at the Luneta. The stars and stripes flag was lowered and the national flag was raised to a 21-gun salute and the pealing of church bells all over the country.

Roxas had a love affair with Jovita Fuentes, the opera singer who sang Madam Butterfly in theaters all over the world. To commemorate her love for President Roxas, she composed that love song, “Ay Kalisud.” Roxas was not open with his extra marital relationships. Mrs. Roxas made him miserable.

My wife remembers that when she was at the Holy Ghost College in 1946, Mrs Roxas went there looking for her husband’s illegitimate daughters. One of them was the mother of former Miss Universe, Margie Moran.

When Roxas was sworn in as President, his task was herculean: to rebuild a nation ravaged by war. Fortunately, the United States helped in the rehabilitation with financial assistance and the presence of several Federal agencies in the country. The sugar industry was revived.

The United States, however, maintained its hold on the country through the military bases and the Parity Rights amendment to the Philippine Constitution, among others.

Next to the bases, the Parity Rights amendment was most controversial because it continued the exploitation of Philippine resources by America. This exchange for continuing economic and military assistance—and the sweetest of them all, the annual sugar quota that perpetuated the political dominance of the sugar bloc on Philippine politics.

Then, too, widespread graft surfaced, together with the rumblings of agrarian discontent. Roxas escaped an assassination attempt by Julio Guillen, a Tondo barber who threw a grenade while Roxas was addressing a Plaza Miranda rally.

Roxas did not finish his term. After speaking before the US 13th Air at Clark airbase in Pampanga, he suffered a heart attack and died.

ELPIDIO QUIRINO (1948-1953)

I knew Elpidio Rivera Quirino quite well. In the manner of Ilokanos honoring their elders or men of high position. I always addressed him as “Apo.” When I was courting my wife, who was living in Tala, where her father was director of the Leprosarium, I would drop by the Novaliches house where Pres. Quirino had retired almost every time, after I visited her at Tala.

He reminisced not just about his presidency and the characters with whom he dealt, but the past. He and Osmeña were the last of the first generation of Filipino leaders that witnessed the birthing of our political institutions from the demise of Imperial Spain and the burgeoning of the American empire.

Quirino was scrupulously clean; all those stories about his lavish lifestyle were concoctions to belittle him in the political campaign that elected President Magsaysay. He was Ilokano after all, frugal, hardworking, happy with simple Ilokano dinengdeng (vegetable stew).

He was born in Vigan, Ilocus Sur, the third child of Mariano Quirino from Caoayan, Ilocos Sur and Gregoria Mendoza of Agoo, La Union. He graduated from the Manila High School then went to the University of the Philippines College of Law and passed the Bar in 1915. He practiced his profession until his election to Congress in 1925, then the Senate in 1931.

In Quezon’s Commonwealth government, he was a member of the Cabinet. During the battle to liberate Manila, on Feb. 9, 1945, Quirino’s family—his wife, Alicia Syquia, his children, Amando, Norma, and Fe Angeles—were killed by the Japanese.

He was elected Vice President in 1946 and became President when Roxas died in 1948. It was at this time that the Huk rebellion erupted, making it his sternest challenge.

In 1949 he won as President. Quirino had a splendid program for the country’s economic development that included agrarian reform, electrification and regionalism.

He also re-structured the Armed Forces, formed the Batallion Combat teams, the Rangers. He created the Social Security Commission. In foreign affairs, he strengthened our ties with the United States with several treaties.

For all those initiatives, Quirino was considered a weak leader and when he ran for re-election, he lost and the man he appointed Defense Secretary won. Quirino bore no ill will towards Magsaysay; for one, both were Ilokanos.

RAMON MAGSAYSAY (1953-1957)

He was flawed, impulsive and because he was intellectually insecure, he listened eagerly to people. Whatever his faults, I consider Ramon Magsaysay as our best President.

He was a game changer, an innovator and he proved we are capable of building an incorruptible government. Maybe it helped that our population then was a mere 30 million; it is now 110 million.

Through the example of one selfless leader determined to walk the talk, he provided us meaningful insights on leadership and how to convince people. I once suggested that if there was a Filipino leader who should have declared Martial law, it was him.

Conrado Estrella, former Pangasinan governor and astute politician said it wasn’t necessary—the people obeyed RM whatever he asked of them. I knew RM personally. He was taller than most Filipinos. His manner was direct, his language simple and down to earth.

He was born in that section of Zambales that is Ilokano. We always talked in Ilokano. He was in Zambales with a bus company when the war broke out for which reason, he was called a mechanic. During the war, he was with the guerrillas and it was during this period that he obtained firsthand experience with the peasantry. I suspect he had had contact with the Huks; he sympathized with them. He was a member of Congress during the Quirino administration when President Quirino appointed him Secretary of National Defense.

The Hukbalahap—short for Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon, was perhaps the best organized guerrilla group in World War II, its leadership mostly communist. During the Occupation, they took over the haciendas that the landlords couldn’t administer. After liberation, however, the landlords, with their civilian guards and aided by the Constabulary returned. In the late forties, the Huks were very powerful. Checkpoints were all over Luzon. Cars, buses going through Central Luzon were in convoys accompanied by armored cars.

In the late 1940s, the Huks were rumored to have ringed Manila. During this period, Huk Supremo Luis Taruc came to Manila with some of his men and I interviewed him. I was then on the staff of the Catholic Weekly, The Commonweal.

President Quirino gave RM a free hand and he initiated a policy of accommodating the Huks. He opened Mindanao and other areas for settlement—the special EDCOR farms. He also focused on community development as the core social program that will bring the government to the people, the same program which Duterte is pursuing today.

Magsaysay got assistance from the United States not only in the Huk campaign but when he ran for President. That assistance was superfluous for Magsaysay was overwhelmingly popular. As President he relied on the best available minds in the country. He was impulsive but if he made a wrong decision, he rectified it immediately.

When he died at the plane crash in Cebu in 1958, many suspected it was sabotage; certainly, because of his many reforms, there are those he had hurt. RM was survived by his wife Luz Banzon and daughters Mila and Teresita and Ramon Jr. who was elected Senator.

Former Senator Ramon Magsaysay, Jr. would later tell me how frugal and correct his father was, that he had to pay for the food served to friends. The Malacañan safe was opened when he died—it was almost empty. The family had no Manila house to go to; Paco Ortigas donated a lot in Mandaluyong for the family and the stevedores at the pier donated the tiles for the roof.

In his honor, the Rockefeller Brothers donated a foundation that honors Magsaysay with a memorial award for outstanding Asians.

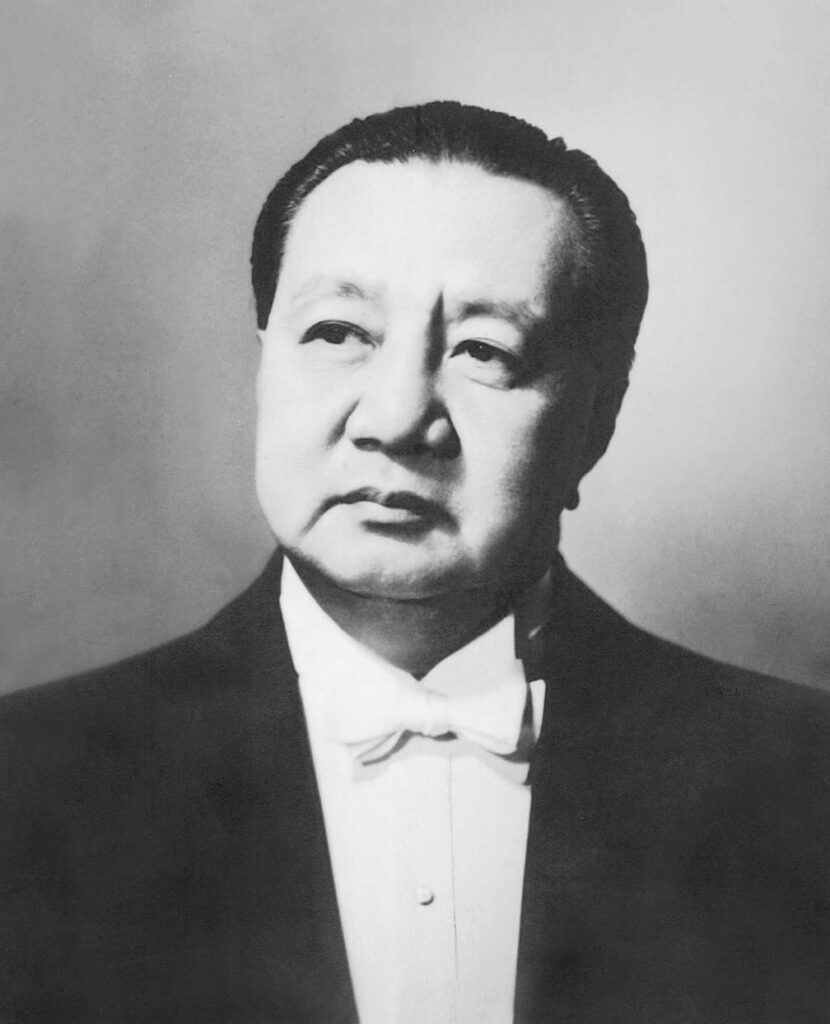

CARLOS P. GARCIA (1957-1961)

Carlos Polistico Garcia was born November 4, 1896 in Talibon, Bohol. He was a teacher, poet, lawyer, a guerrilla during the Occupation, military leader and the 8th President of the Republic.

As a student of our history, what bothered me all these years, is why he was unable to continue Magsaysay’s legacy of clean government. The Lopezes had lured him; he gave them the giant power company Meralco, for nothing.

I invited him to address a National Writers Congress in Baguio sponsored by the Philippine PEN in 1958. He was like Recto who also addressed that conference as an avowed nationalist. He espoused a “Filipino First” policy, favoring Filipinos investing in the country over foreigners. As a poet, his plea for Filipinos to care for “temples and altars” was portrayed, but alas, wasn’t effective enough to make Filipinos build a moral and just society.

In the face of mounting economic difficulties, he started an “austerity” program to prevent abuses in the export licensing and restrict government imports, and most important of all, increase food production.

It was during his term that the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) supported by American foundations was set-up in Los Banos. The Institute is instrumental in the increase in rice production in the region as well as the creation of pest-free varieties.

In the 1961 election, he ran for re-election but was defeated by Diosdado Macapagal. He retired to Tagbilaran, Bohol and later, in Quezon City. He died of a heart attack in June 14, 1971.

President Garcia was married to Leonila Dimataga. They had one daughter, Linda Garcia Campos. As with most Filipino leaders who professed nationalism, that profession was not a sustained effort to abolish poverty.

DIOSDADO MACAPAGAL (1961-1965)

Diosdado Macapagal—Cong Dadong, the “poor boy from Lubao,” was hobbled among other things by a shrewish wife.

I was in Malacanang one early morning and I came upon Mrs. Macapagal berating the janitors.

Macapagal was President from 1961 to 1965. He graduated from the University of Santo Tomas and the University of the Philippines and was elected Congressman in 1949. In 1957 he became Vice President to President Garcia whom he defeated in 1961.

Born on Sept. 28, 1910, in Lubao, Pampanga to very poor parents, his lineage, however, includes Don Juan Macapagal, a Tondo prince and the great grandson of the last reigning Lakan ng Tondo.

Cong Dadong was also known as a poet in both Capampangan and Spanish. After high school, he enrolled at the Philippine law school on a scholarship, supporting himself as an accountant. Running out of money, he returned home and joined his boyhood friend, the movie star, Rogelio dela Rosa producing zarzuelas—Tagalog operettas.

He married his friend’s sister, Purita dela Rosa in 1938 with whom he had two children. Purita died in 1943. Three years later, he married Dr. Angelina Macaraeg on May 5, 1946. The marriage bore two children, Diosdado, Jr. and Gloria.

With the backing of the philanthropist, Honorio Ventura, he went back to law school. He passed the bar in 1936 and also earned a doctorate in economics.

Macapagal was Quezon’s legal assistant and during the Occupation continued working as such for President Laurel. After the war, President Roxas appointed him head of the Department of Foreign Affairs Legal Division.

In 1948, President Quirino appointed him chief negotiator in the transfer of the Turtle Islands in the Sulu Sea to the Philippines. The following year, Macapagal was appointed as second Secretary in the Philippine Embassy in Washington and counsellor on Legal Affairs and Treaties.

On the urging of Pampanga’s political leaders, Macapagal was returned home to run for Congress. He won and also was re-elected for another term.

As a lawmaker, Macapagal authored several laws benefitting the poor, among them the Minimum Wage Law and so many others.

In the election of 1957, he won as Vice President, and was now the opposition leader. As Vice President, he went around the country gaining followers and in the 1961 election, he defeated re-electionist Carlos P. Garcia.

As President, Macapagal presented an economic program based on free enterprise. Exchange controls were lifted. He improved the agrarian reform program, provided funds for the purchase of agricultural lands for distribution to the landless.

Macapagal pledged to rid the nation of corruption that ballooned under President Garcia. He also antagonized the powerful Lopezes. It was also at this time that GI-turned-entrepreneur Harry Stonehill was building his empire based on collusion with government officials.

During his term, Sabah was claimed by Malaysia. One notable move made by Macapagal was to transfer Independence Day from July 4 to June 12, at the urging of his Education Secretary, Alejandro Roces.

In spite of his poor beginnings, Macapagal failed to win the masa. His manner was correct but he didn’t pander to them. His graft ridden regime diminished him and in 1965, he lost the election. Beribboned “war hero” and garbed in “shining armor,” Ferdinand Marcos won an overwhelming victory.

The “poor boy” from Lubao had moved to Forbes Park. During the Martial Law years, he often dropped by the bookshop to reminisce. He told me he didn’t realize it was so easy to be a dictator. He did some writing. In April 1997, he died of heart failure and pneumonia and his remains are at the National Cemetery.

FERDINAND E. MARCOS (1965-1986)

Contrary to gossip, Ferdinand Marcos was not henpecked by his wife. He was perhaps the most intellectually prepared President we ever had.

There was no reason for him to have failed. He surrounded himself with the brightest Filipinos in his time, some of them, my personal friends. It would have been easy for me to ingratiate myself with him—my being Ilokano most of all.

But I kept away from him. When I was at the University of Santo Tomas in 1946 one of my classmates was Jose Nalundasan, the youngest son of Julio Nalundasan who was widely believed to have been shot by Marcos.

Peping Nalundasan was absolutely sure it was Marcos who did it. Marcos defended himself ably in the Supreme Court presided by Chief Justice Jose Laurel. I followed Marcos’s career. I know for instance, that when he was a congressman, he was already wealthy, and more so when he became Senator. His marriage to the beautiful Imelda Marcos further glamorized him.

Marcos knew in his bones he needed the Army as partner in declaring Martial Law. He “Ilokanized” it. Officers on the right side of the Agno River—the solid Ilokano North, were given preference in status.

Fidel Ramos, his cousin who later became President—however, believed Imelda changed Marcos. His marriage to Imelda for all its glitz and glamor was tumultuous. Discovering Marcos’s affair with Dovie Beams, Imelda used this to clobber Marcos and get concessions. Once at a dinner, Hans Menzi told us of the troubled relationship, saying, he had to leave to go to Malacañan as peacemaker.

Marcos stayed in power for almost a generation, denying the ascendance of the next generation of leaders. He and his wife touched many lives and created a massive and loyal following.

Marcos’ first Martial Law decree abolished the tenancy system; replacing it with a leasehold scheme. This decree was what the peasantry had been longing for. Even Magsaysay with his vast popularity couldn’t get Congress, dominated by landlords to pass it.

Marcos also embarked on a massive infrastructure program while his wife built the Cultural Center of the Philippines and those medical centers. Marcos established relations with China and Russia and abrogated our defense treaty of 99 years with the United States. If he did not, the US bases would have become permanent like Guantanamo in Cuba.

Marcos knew he had to win military allegiance, so he Ilokanized the Army. Officers got promoted on the basis of their geographical origin—the right side of the Agno River which marks the southern boundary of the “solid” Ilokano region.

Marcos was elected to a second term and in 1972, he proclaimed Martial Law, claiming to prevent Communism from taking over the country.

The first months of Martial law were accepted by the people; sure, there was a sense of security. The oligarchy, too, was dismantled, but soon enough, Marcos created his own oligarchs with him on top.

But Marcos was correct in abolishing the two houses of Congress and replacing it with one Assembly. We can see how much money is wasted supporting both houses. If there will be Constitutional change, I hope the unicameral assembly will be restored.

The Marcosses are back; as Singapore’s former Prime Minister said, only in the Philippines…Bongbong Marcos, Marcos only son, already served as Senator. Malacañan is within his grasp. President Duterte is a self-proclaimed champion. Of cleaning government, he allowed what has been long perceived to be as the most corrupt Filipino President to be buried in the National Cemetery.

That perceptive English writer, James Hamilton Paterson, who wrote the Marcos biography, “America’s Boy,” said Marcos got everything, power, wealth, women said he was bored.

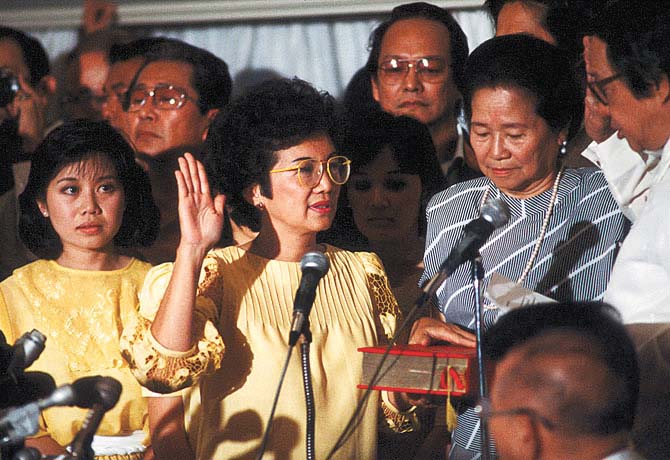

CORAZON COJUANGCO AQUINO (1986-1992)

As President, Corazon Aquino was a disaster. She used to come to the bookshop and I’d select the books for her husband who was then in jail. She would return them within the week. I hardly had any conversation with her. In those times that I visited Ninoy in their Quezon City house, she never participated in our talks. She left after she had served us merienda and snacks. It was obvious why Ninoy married her. I had a feeling she resented her husband, for when she became President, she distanced herself from the people who she knew were close to Ninoy and much of what she did benefitted her relatives.

The assassination of her husband on August 21, 1983 is a major milestone in our history. His massive funeral, the likes of which has never been seen in the final denouement of the Marcos dictatorship, but it took a couple of years before the EDSA Revolution erupted.

Those of us who were there, who witnessed it, exalted in a manner so joyous, thinking about it now, so many years after the event, still lifts the heart.

In the snap election the Americans suggested and which Marcos approved, Cory Aquino was reluctant presidential candidate.

Marcos cheated but courageous election officials denied him. At this time the very people who helped him declare Martial Law—Juan Ponce Enrile and Fidel V. Ramos, had formed a cabal to overthrow him.

Cory Aquino was a saint, regarded as redeemer but she turned that EDSA revolution into a restoration. She returned the sequestered properties of the Lopezes and reversed some of the few good things Marcos did.

We were warned; on her first day in power, she announced she will “not accept unsolicited advice,” that she will make the presidency “an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. job.”

I knew her husband very well. I was his first editor when he joined the Manila Times in 1950. I had hoped he had influenced her, but as it turned out, he didn’t.

She resented the men with whom Ninoy worked closely. More than this, a high palace official also told me she was “mata pobre.” She went to the United States and delivered a beautifully crafted speech before the American Congress. She was the darling of the press. Maybe we expected too much from the housewife which she said she was.

FIDEL VALDEZ RAMOS (1992-1998)

One memorable achievement of President Ramos was he destroyed the telephone monopoly. I recall how difficult it was then to obtain a telephone. To aggravate the condition, the service was also very bad.

General Fidel V. Ramos, anointed by Cory Aquino to succeed her, was elected President in 1992. He comes from Asingan, Pangasinan. His father, Narciso was Congressman, then Secretary of Foreign Affairs and Ambassador to Taiwan.

Ramos commanded a contingent in Korea during the Korean War, and also in Vietnam. He is a graduate of the US Military Academy in West Point and is also an engineer. He is one of the truly qualified leaders to run this country but his regime was lackluster.

For one, he faced tremendous problems left by an incompetent Cory government—the severe power outages among them. Emergency power generators had to be built.

Fort Bonifacio—that huge military base in Taguig was sold—the proceeds to be used in the modernization of the Armed Forces. This did not happen. This is his major failing. As a military man with excellent contacts in Washington, he could have done this.

Ramos decriminalized the Communist Party which continues to wage a “protracted war” against the State.

I am tempted to conclude this was a big mistake but I also realize we need the Communist Party and its contrary goal like we need a good vaccine to grow anti-bodies—the ultimate defense—in our system. No re-bel movement can sunder the Republic now.

It is important to mention President Ramos’ younger sister, Leticia who married an Indian academic. A Sorbonne graduate, she was also an outstanding senator and diplomat.

JOSEPH EJERCITO ESTRADA (1998-2001)

Joseph Estrada, otherwise known as Erap, is our lover boy President. Only he knows the number of his women; his illegitimate children. But he took care of them.

His legitimate wife, Dr. Luisa Pimentel, bore him three children—Jinggoy, Jackie and Jude.

Dr. Pimentel is my wife’s childhood friend. Early on, she told me she was going to leave Erap, I told her, don’t, so she stayed on and became a Senator.

Estrada won the presidency in the 1998 elections on the basis of his popularity as a movie actor, portraying a macho defender of the poor in about a hundred films.

He was born to a wealthy Tondo family which moved to San Juan. Erap did some good as an individual. He founded Mowelfund which assists movie industry workers in great need. It also granted scholarships and trained scores of workers in the entertainment industry.

In 1977, the government signed a peace agreement with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) but soon after, the MILF engaged in terrorist attacks on civilians and the military.

On March 21, 2000, Estrada ordered an all-out war against the MILF and all the MILF camps were over run.

The President went to Mindanao and promised to bring peace and development to Mindanao. Hundreds of MILF fighters surrendered. An uneasy peace came to Mindanao but, as events have shown, only for a while.

Estrada’s education was haphazard. He was kicked out of the Ateneo High School for misconduct. He enrolled at Mapua Institute of Technology, then the Central Colleges of the Philippines engineering college but also dropped out. He had, however, practical political training starting as Mayor of San Juan in 1969.

In 1987 he was elected to the Senate where he and 11 other senators voted to end the Bases Agreement with the United States. In the 1998 elections, he ran for President and won.

Estrada’s government was soon burdened by debt and tainted by corruption. Ilocos Sur politician, Chavit Singson, alleged he had given Estrada millions, hidden in a bank account of “Jose Velarde.” An impeachment charge was filed.

On the evening of January 16, 2000, the impeachment court decided not to open an envelope that was supposed to contain evidence of Estrada’s guilt. And that night thousands gathered at EDSA. The Army Chief of Staff, Angelo Reyes, withdrew support for Estrada, and the next day the Supreme Court Chief Justice swore in Gloria Macapagal Arroyo as President.

Tondo born sociologist, Aprodicio Laquian was lured by Erap to return to Manila and help. He returned soon enough to Canada for as he said, Erap had made Malacañan a gambling den and a bar.

Estrada returned to San Juan. He was judged guilty of plunder by the Sandiganbayan—the first President to be impeached and convicted.

President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo granted him executive clemency.

Eager to redeem himself, he ran and won as Manila Mayor in 2012. He repeated the feat come the following election year. He ran again in 2016 but was defeated by Isko Domagoso.

GLORIA MACAPAGAL ARROYO (2001-2010)

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, President Macapagal’s daughter, was superbly prepared for Malacañan like former Pres. Fidel V. Ramos. She is an economist, honed in government service, and a polyglot.

Like her American counterpart, U.S. President George W. Bush—son of U.S. President George H.W. Bush—Arroyo was the first Philippine President whose father had been likewise a President.

This feat will be repeated again in the time of the late Pres. Benigno Aquino III, son of the late Pres. Corazon C. Aquino.

Arroyo was in Malacañan from June 20, 2001 to June 30, 2010, taking over from Pres. Estrada, who was ousted in 2001. For this reason, her term took longer than the normal six years. She is the longest serving President in the post-Marcos era.

Arroyo was born on Apr. 1, 1947. She studied economics at Georgetown University in the United States. Former American President Bill Clinton was her classmate. In 1968, she married Jose Miguel Arroyo, a landlord and lawyer from Negros.

While an Economics professor at the Ateneo University, Noynoy Aquino, another future President, was her student.

On the invitation of Pres. Cory Aquino, she became undersecretary of the Department of Trade and Industry. After serving as Senator from 1992 to 1998, she was elected Vice President.

In 1992, Gloria ran for the Senate and won; she sponsored a slew of bills, most of them on human rights, trade and commerce.

During the 1998 election, she ran as Vice President. Though belonging to the opposition, she won.

Estrada, who won as President, appointed her Secretary of Social Welfare and Development. She later resigned from the position to distance herself from Estrada, who was by then already beleaguered by corruption charges.

During her first term as President, she presided over the country’s close relationship with the United States, which included the country’s participation in the American war with Iraq, as well as the ratification of the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA).

While she had a splendid economic program, her presidency was soon tainted with election scandals like “Hello Garci.” These scandals peaked with the Oakwood mutiny, calls for her ouster, among others.

After her term, Arroyo was arrested twice and held at the Veterans Hospital in 2011. She was charged with electoral sabotage and misuse of lottery funds. Facing prison, Arroyo pleaded for hospital arrest, wearing a neck brace to emphasize her health condition.

In 2016, Arroyo redeemed herself politically by running for Congress and becoming Speaker of the House, the first President to “diminish” herself officially to obtain power, the Presidency being limited to just one term by the Constitution. This is what President Duterte seems to be aiming for—to run for the office of the Vice President when his term ends next year.

It was President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo who gave me the National Artist Award.

BENIGNO SIMEON “NOYNOY” COJUANGCO AQUINO III (2010-2016)

I had a grudge against President Noynoy. A month after he became President, I asked to interview him for the International Herald Tribune, now The New York Times. His father was a very close friend and I wanted to find out how much he had influenced his son. I got no reply even after I pursued my request. Then, he gave an interview to Vice Ganda, the TV comedian.

Noynoy Aquino III was a reluctant presidential candidate but was propelled to the Malacanan on the basis of his mother’s death in the same manner that Cory Aquino was elected President on account of her husband Ninoy’s assassination.

Come the 2010 elections, he defeated rivals Joseph Estrada, Manuel Villar and Gilbert Teodoro.

His first pronouncement as President was to say his “boss” were the people. He banned sirens unless they came from ambulances and the police.

Aquino embarked on an infrastructure program of roads and transport systems and accomplished an impressive 6.8 growth as confirmed by the World Bank.

His regime, however, started with the botched rescue operation of Hong Kong tourists at the Luneta, ending in the death of 20 tourists. Then, there was the Mamasapano massacre, where 40 policemen were killed by Moro rebels.

It was during his term that the deadliest typhoon ever, Yolanda, devastated the Visayas. Hundreds were killed and rehabilitation is still ongoing. His response was sadly lacking.

The Napoles scandals later surfaced illustrating how millions can easily be stolen from government with the complicity of politicians.

To the best of my knowledge, Noynoy displeased his uncle, Peping Cojuangco. Aquino did not pay much attention to Hacienda Luisita, the Cojuangco prime property.

He illustrated his courage when he filed before the UN Permanent Court of Arbitration a case against China’s grab of Philippine territory; the rest is history.

Aquino, popularly called “PNoy,” was our only bachelor President. He never married although he was seen with several women. He loved fast cars and video games. He was very low key and self-effacing, preferring solitude for which reason, media called his condition “noynoying.”

He was judicious in his handling of government funds. With the aid of budget Secretary Butch Abad, he channeled government money in areas where it was most needed. He was severely criticized for this.

He had been ill for some time and had regular dialysis treatment. He died in his sleep. President Duterte rendered him honors and his remains are in the Manila Memorial Park together with his parents.

In death, I am learning to appreciate him more.

RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE (2016-2022)

Davao’s colorful mayor, was voted President on the basis of his popularity as Davao mayor. He had cleared Davao of the New People’s Army grip, and of criminality. Never mind that he did all these with his alleged death squads.

He is now on his last year as President and as I said earlier, he may yet be the best President we ever had next to Magsaysay.

His popularity is highest in the working class, particularly with the Filipino overseas workers. With his endorsement, political nobody’s like Bong Go and Bato dela Rosa are now Senators. I’ll try to explain his popularity, much of it accrues from his vulgarity. It had shorn the current political vocabulary of its hypocrisies.

Duterte, however, is vulnerable on so many issues, most of all his pandering to China. We won our case vs China in the International Court. Instead of our foreign policy exploiting this victory, he has all but discarded it.

For sure we can’t afford a military confrontation with China but we are not powerless in the face of Chinese bullying. Duterte threatened to cut off our Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) with the United States—when we need that alliance most.

When he took office, Duterte promised to solve the drug problem in six months. More than six months and five years later, the drug problem festers after hundreds have been killed.

I suggested he adopt the Singapore solution, go after the drug lords, and most of all, close the sources in China. It is close to impossible to obtain hard evidence on corruption but we can see it in the lifestyle of the corrupt. So, they get fired when they should be jailed, their ill-gotten wealth sequestered.

Duterte is brave—in his first address before Congress, he bluntly told those politicians he owed them nothing. Then he did what no Filipino leader had done—he challenged the oligarchy, the arrogant media, and yes, the powerful and complacent Catholic church.

His critics have criticized him for his dictatorial proclivities, for muzzling the press. He took advantage of a weak justice system and jailed Senator Leila de Lima without trial. But contrary to charges that he had muzzled the press, he has not jailed a single journalist or closed a single paper.

What Duterte has done is make the country safer than any other time. He mo-dernized the Armed Forces as no President had done, gave it new ships, new planes.

He has also brought peace to Mindanao and we pray that it will last. Many infrastructure projects were completed, and our foreign reserves are at its highest.

But our economic development, interrupted by this pandemic, will presumably be resumed. His most visible achievement: he cleaned up Manila Bay. He knows however that he had polarized the country instead of uniting it.

Like Marcos he coddled the Armed Forces and maintained the superiority of civilian rule. Many Filipinos, however are apprehensive, like Marcos, he may stage a coup, too.

For all that he has achieved, he may then be the worst President next to Marcos.

OUR POLITICAL PROCESS

Compared to other Asian countries with their venerable pasts, we are a very young nation.

Since we became Christians, we belong to the Western tradition and we have tried to build our political institution along the Western model. We had two political parties that formed a government. We have seen that two-party system eroded into the multi-party system now.

Our political parties, however, with the exception of the Communist Party, are not based on any ideology. They converge on personalities to this very day, anchored as they are on our hankering for a strong leader, a father image—a redeemer who will lead an anarchic and apathetic people to nationhood.

While we understand and protect our political freedom, we will also welcome a dictator that will provide us with security. This is what Marcos showed in 1972.

We must therefore be vigilant in nurturing our political institutions, starting with the local government units—the barangay, keeping in mind that institutions can only be as strong as we are.

The political process—the election campaign—has also morphed as specta-cular showbiz events with showbiz stars singing and dancing, the candidates doing the same. The advances in information technology have made campaigning more challenging and innovative.

The major challenge that our institutions and our leaders face is poverty, and how we can free ourselves from it to create a free and sovereign nation. It took Western nations centuries to achieve this; we aspire to do it sooner.

The multi-party system that emerged after Martial law has not changed the political dynamics as we can see now how our politicians seek partnerships and alliances based on popular following.

Nowhere among them is there a fundamental desire to form a party based on moral values; I repeat moral values. If a state has to endure and provide justice for its people, that state must have a strong moral foundation.

Morality in government was an issue, among others, in the First Republic. The ilustrados wanted to set up an institution to raise money for the Revolution. Mabini saw it as an attempt for them to get richer. He opposed them—for which reason he was eased out of the Aguinaldo cabinet. From Tarlac, he fled to Rosales and I made him a major character in Po-on.

The American colonial policy created the Filipino oligarchy that has since then obstructed our development. As Salvador Madariaga, the Spanish writer said, “a nation need not be a colony of a foreign power—it can be colonized by its own elites.” That aborted 1896 revolution must now be revived to destroy this oligarchy if we are to be truly a just and sovereign nation.

Meanwhile, our political institutions are slowly evolving to conform with the emerging economic conditions that underline Filipino culture and the modernizing impulse.

In this regard, I’ve asked separately two Japanese social anthropologists, Masaru Miyamoto and Yasushi Kikuchi—both have studied the Philippines for decades—are we a nation now? They gave the question some thought then both said, “you are going there.”