“The world pays a premium not for occasional flashes of brilliance but for sustained commitments to the performance of tasks.”—Blas F. Ople

On Feb. 3, 1927, a baby to be later named Blas Fajardo Ople, was brought into the world by Segundina and Felix Ople. The couple chose the name Blas after Saint Blaise, whose feast day was on the same day.

The Blas they raised in a tiny house at the village of San Miguel, Hagonoy town, Bulacan province would grow up to become one of the country’s most revered statesmen.

As a child, Blas was frail and sickly. That he did not have an easy life became a recurring theme in his writings.

In an essay for a Bulacan paper, he wrote:

When I was a boy, growing up in Bulacan, of a fragile constitution and uncertain health, I thought I wouldn’t live beyond twenty. I overcame these frailties through hard manual labor, as a farm worker and as a fisherman along the Manila Bay, and later, as a stevedore in Manila’s North Harbor. In my most private moments, I tried negotiating with God to let me live to the age of 35.

The sickly child would grow up to be a warrior, enlisting in the guerrilla movement to fight the Japanese army.

Almost 17, Blas would become the first lieutenant of the Del Pilar Regiment, Bulacan Military Area during World War II.

His choice was clear: Stay in Hagonoy and be at the mercy of Japanese troops who began teaching Nihonggo to the brightest young men in town or leave and take up arms against the enemy. He made the second choice.

He fought and left his family for the hills. As an adult, Blas would be tight-lipped about his days as a guerrilla. The horrors he saw and went through had been hidden deep beyond the reach of his prolific pen.

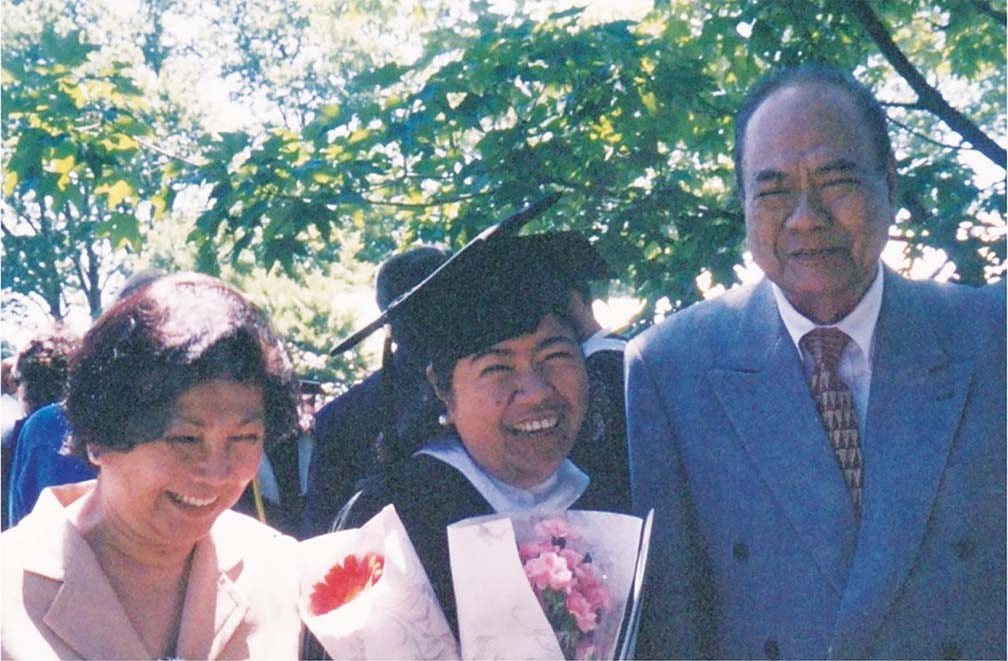

In his 20’s, Blas married Susana, his townmate from Hagonoy, a public grade school teacher.

Susana, who went by her nickname “Saning,” looked after Blas and their expanding family, saving as much money as she could to pay rent and stay in a place long enough for their kids to stay in school.

It was a tough life—even as a newsman for the Daily Mirror, Blas did not earn enough for his needs and, true to the occupational hazards that most journalists face, took to after-hours drinking.

At the age of 25, without a college diploma, Blas went to work for the then premiere news source in the Philippines, Manila Times-Daily Mirror.

He wrote a column, titled “Jeepney Tales.” He was also a deskman and general assignment reporter.

Later in life, he would take pride in his background as a journalist as writing was his strongest suit, even in future endeavors. As a columnist, he won’t miss a deadline, including that imposed on him by national publications like Philippines Graphic, even as his duties as senator and foreign affairs secretary required all his time.

Reading his “Jeepney Tales” columns, one can glean the spirit of merriment and optimism that resided in Blas. As columnist, he would intentionally misspell some words, and would also poke fun at mulcting cops, his “passengers,” lazy city councilors, Mayor Arsenio Lacson, and so many others. He was never hurtful, though, and was often reflective of even the most mundane things.

Take his September 25, 1952 column, for example:

Notice how some jeepney drivers angle those efficient little mirrors so they can get the best view of the pretty faces in the rear? Next thing the jeepney probably smashes against a post but expect the poor innocent brakes to get the blame as usual.

I guess this trend to put up mirrors everywhere comes naturally with civilization. We moderns try to polish up things—our shoes, furniture, etc. Some people even manage to have their bald plates so shiny.

Probably we are not so keen about polishing up our manners and such outmoded stuff. And we’d surely rebel if anybody tried to hold up a mirror before our heart. Who ever heard of such a thing?

As a journalist and writer, he had ease with words, the kind that comes naturally to a voracious reader. As a boy, Blas read the works of Jose Rizal, the Book of Knowledge, newspapers and all kinds of publications. He taught himself through reading.

“I loved to read even scraps of newspapers and books during my boyhood years. I absorbed all the knowledge that the library of Hagonoy Elementary School could offer.”

His sister, Anatolia, recalled Blas, as a child, sitting under the shade of a tree in their backyard engrossed in books. While other boys his age played outdoors, her brother preferred the company of books.

His parents shunned the advice of close friends and neighbors for Blas to leave school and start work as a farm hand. His teachers persuaded his father to let him stay in school, assuring him that what he had was a gifted child. His father, Felix, listened, and agreed. He felt vindicated after his son graduated as school valedictorian.

Blas delivered his first public address as school valedictorian of the Hagonoy Elementary School and was given a standing ovation by his schoolmates and the entire audience. It was a lesson in recognizing that every achievement required hard work and came with pain and challenges. The school valedictorian tried hard not to wince in pain as he wore shoes too small for his feet, borrowed from a rich uncle.

When his father, Felix, died, Blas was already a household name, working for then President Ferdinand Marcos as labor minister.

Blas felt sad and helpless as he peered into the glass pane that separated relatives from patients in the hospital ICU. He saw his honest, hardworking father struggle to stay alive in the ICU of a private hospital.

Before he passed, Felix entrusted to Blas the tools he used to repair fishing boats. That powerful moment, seared in the pain of losing a parent, left an indelible mark on the soon-to-be architect of the Philippine Labor Code. Honest work, fair wages, freedom of association, and all other principles that would form the bedrock of labor justice sprang from that simple request—a father asking his son to care for his work tools.

There’s dignity in honest work, one that must endure and be respected at all costs.

LABOR INFRASTRUCTURE OF THE FUTURE

Younger people of cosmopolitan descent would often inquire about the meaning of “Ka” before the name of Blas Ople. What does those two letters stand for? Some say that Ka is short for “Kapatid” (sibling) and is often used to show respect for one’s elders. Bulakenyos still refer to Ople as Ka Blas until today in a gesture of respect, if not reverence.

As the country’s longest serving labor secretary, Ka Blas provided the infrastructure that remained mostly intact, nearly 50 years hence.

Workers receiving minimum wage are protected by the Labor Code that he authored precisely to make sure that no Filipino is forced to accept salaries that are unjust and below legally-mandated levels.

Employees—whether private or government—can also thank Ka Blas for the additional benefit of a 13th month pay which became mandate through a presidential decree issued in the 1970s during Ka Blas’ tenure as labor minister.

In 1975, Labor Secretary Blas F. Ople became the first Filipino to be elected president of the 60th general assembly of the International Labor Organization (ILO) in Geneva, Switzerland. Ople delivered his acceptance speech in Filipino, which was translated into different languages for the delegates to hear

He laid the foundation for labor relations as labor minister, giving life and true meaning to the concept of tripartism, to involve not only workers and employers, but also government, in achieving the goals of social justice, fair compensation and decent work environments.

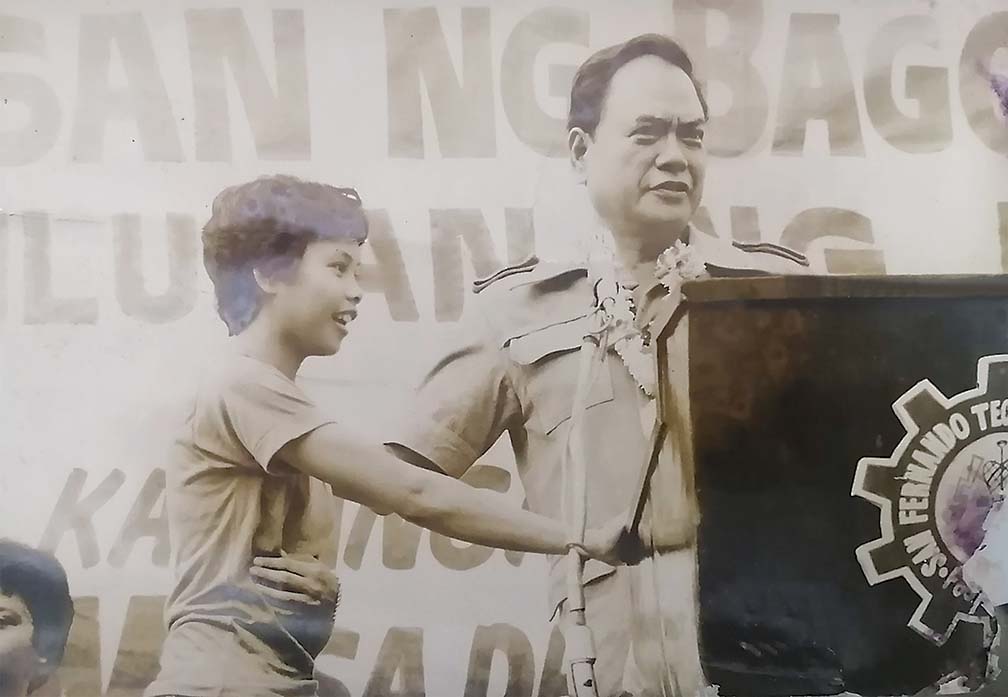

Secretary Blas had the audacity at that time, when patronage politics and nepotism were perks of the elite, to put an ad out in major dailies calling on young people to join his department. He assembled his management team by welding the experienced bureaucrats with the eager-to-serve newbies, several of whom later on succeeded him as labor secretaries.

One of those “newbies” was Nieves R. Confesor.

She recounts: “I was caught—a “wannabe” free spirit—in the service of a government that was known to be everything I did not want. But the “blind” ad called for the brightest who wanted to work on social policy, evaluation and formulation, etc. And I responded by sitting at day-long exams and facing a battery of interviewers, half of whom, like me, had also come in from the “cold.” And then, the Minister of Labor himself. And a promise to work for a year, and then two years.”

“The “young” generation—Pat Sto. Tomas, Ruben Torres, Benny Laguesma, Chito Brillantes—would later be called upon to head the DOLE. And Manolo Abella, Carmelo Noriel and Lucy Lazo would become part of the global civil service at the ILO. Ka Blas, had instituted not only a formidable team to work with him in shaping the new “age,” but a deliberate program of succession planning.”

If there ever was a study on best practices regarding continuity of vision, policies and programs in a single government agency, one only has to revisit those golden days of the labor department and how the proteges of Ka Blas kept his vision going through their own unique and inclusive leadership styles.

FATHER OF OVERSEAS EMPLOYMENT

At the intersection of EDSA and Ortigas Avenue stands a building that houses the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA), where thousands of Filipinos dreaming of going abroad would go, during pre-pandemic times.

The building was named after Blas F. Ople during the time when Patricia Sto. Tomas, one of his proteges, was appointed by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo as labor secretary.

It is a fitting reminder of how intertwined the life of Ka Blas was with the nearly 50 years of overseas employment history. It was his ardent wish that overseas employment would be a stop-gap measure.

“The time will come when foreign capital, the excellence of the Filipino worker and technology would converge in the Philippines thus creating a multitude of jobs to enable our workers to stay home,” he said.

That never came to pass during his lifetime, and soon a new department for migrant workers will become operational, to look after the welfare and needs of those who vote to leave with their feet, in pursuit of better incomes abroad.

According to former labor secretary Marianito Roque, the Philippine labor situation during the 70’s made it necessary for the State to intervene and organize the recruitment and deployment of Filipino workers to foreign job sites.

During those days, there was a surplus in the labor force and minimum wage stood at P8 a day. Travel agencies acted as employment agents, and the Middle East countries were on a massive infrastructure development spending spree thus necessitating foreign contractors and foreign workers.

Order was put in place through overseas employment contracts that specified round-trip air tickets, board and lodging, emergency medical and dental coverage, guaranteed basic wage, overtime pay, workman’s compensation, grievance machinery, repatriation, enrollment of employers, and workers’ protection at no less than what is prevailing at the worksite.

Institutions such as the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration and the Welfare Fund for Overseas Workers, the predecessor of OWWA, were created to ensure the proper regulation of licensed agencies as well as onsite welfare services.

During the first year of overseas employment during the watch of Secretary Ople, around 14,000 workers left to work abroad. Pre-COVID-19, the annual deployment of overseas Filipino workers was at two million a year. More than four decades hence, overseas employment has become a pillar of the country’s economic recovery strategy, and a main contributor through million-dollar remittances that help fuel consumption-spending across the archipelago.

OWWA Administrator Hans Leo Cacdac recently paid tribute to Ka Blas during a recent joint webinar of the BusinessMirror and the Blas F. Ople Policy Center, noting that even today’s COVID-19 efforts to assist returning OFWs sprung from the seeds planted by then Secretary Ople in 1983. It was during those days that Ople designed a one-stop document processing center for OFWs, a service that is continued by the POEA and OWWA, 39 years hence.

Cacdac said, “Ople designed the basic framework that still exists to this day for OFW protection. He did not design a parthenon which just stands as a tourist spot these days but as a structure where OFWs metaphorically and maybe even literally, seek solace and protection. It was LOI (Letter of Instruction) 537 in 1977 where the OWWA was instituted through a welfare and training fund. And this is where you will see the visionary that Ka Blas was. Back then in 1977, which was about the 45th year, he already designed a framework for OFW welfare and protection and he had the foresight to determine the sustainability of the effort that’s why there was a welfare and training fund instituted. Of course it was not just as welfare fund but a training fund to develop the future skills of OFWs because as far back as 1977, Ka Blas saw skills as the foremost measure of protection. It is almost unfathomable that someone like Ka Blas saw these things way, way, way before everybody else came in.”

FRAMING THE CONSTITUTION

People Power had succeeded in ousting President Ferdinand Marcos from power, and many of those who benefited from the regime fled in fear of reprisal. Secretary Ople was in Washington D.C. during those tumultuous times, on a special mission from his President, to talk to key officials of the Reagan administration.

His DOLE subordinates—Willie Villarama and Patricia Sto. Tomas—were also in the US for their mid-career course at the Kennedy School of Government in Cambridge, Boston. Willie decided to fly to Washington, DC to help his former boss the best way he could.

Also with Ka Blas during these heated and risky times was Manuel “Manny” Imson, a trusted DOLE official. When Secretary Ople had the difficult task of informing his own boss, President Marcos, that it was indeed time to cut, and cut cleanly, Willie and Manny saw the enormous strain on Ka Blas’s face. After his failed mission, the suddenly jobless labor secretary decided to pack up his things and head home. Both Villarama and Imson were against his decision, out of fear that their former boss would be an object of hate and ridicule, given his ties with the exiled president.

Dejected but unbowed, Ka Blas merely said that he had not wronged his country in any way, and he would like to return home. Had he chosen to stay behind and pursue political asylum in the United States, the country would have been bereft of a great intellectual and nationalist, in the roster of its constitutional framers. But choosing life in a foreign country has never been an option for Ka Blas.

He was appointed by President Corazon C. Aquino as a member of the Constitutional Commission of 1986 on the criteria of “integrity, probity, patriotism and nationalism” set forth in her Proclamation no. 9.

It was Executive Secretary Joker Arroyo who reached out to Ople offering him a seat in the Constitutional Commission as a representative of the opposition.

Ka Blas accepted and brought with him former Bulacan assemblyman Teodulo Natividad, Atty. Regalado Maambong and Atty. Rustico delos Reyes. During the ConCom debates, the man from Hagonoy, Bulacan contributed a significant share of the provisions, though not being a lawyer, or even a college graduate.

ConCom president and later on Supreme Court Justice Cecilia Muñoz-Palma had this to say about Commissioner Blas Ople:

“He authored the ‘people’s initiative’ as a third mode of amending the Constitution. His legacy, however, is embodied in the article on ‘National Economy and Patrimony.’ It provided that the goals of the national economy are a more equitable distribution of opportunities, income and wealth for the benefit of the people and to raise the quality of life of all, especially the underprivileged. To this end, the State shall promote industrialization together with agriculture development and agrarian reform.”

As one of the framers of the Constitution, he was responsible for ensuring that workers’ right to self-organization and employment security are protected by the fundamental law. He also authored the provision on regional autonomy that paved the way for an enabling law creating the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM).

The reason why the highest annual appropriation is allocated to education is due to Constitutional Commissioner Ople. That the young boy of Hagonoy—who stood before his class as a valedictorian wearing borrowed shoes that hurt his feet—could have brought about this pivotal billion-peso investments in the education of present and future generations is a testimony to God’s generosity of spirit. Yet, never had Ka Blas once been heard boasting about this, not before media or even among friends.

As in all of his stints in public service, it is his love for words that brought to life his own passion for public policy. Justice Adolf Azcuna, who joined Ka Blas in the ConCom, wrote:

“With an intellect that knew no bounds, a heart that was one with the poor and the disadvantaged, and a gift for articulation, Ka Blas tackled the full range of the agenda— from education to labor to the environment.”

“On another occasion, the Committee on Declaration of Principles and State Policies, spearheaded by Ed Garcia, proposed a recognition of the right of nature to follow its own rhythm and harmony. After the lawyers in the body restated the right as belonging to the people, since nature is not a person and only persons have rights under the law, Ka Blas helped rephrase the proposal into its present colorful language:

“The State shall protect and advance the right of the people to a balanced and healthy ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature.” (Sec. 16, Art. II, Declaration of Principles and State Policies).

Ka Blas also crafted and fought for a provision that can be found in Section 14 of Art. XII on National Economy and Patrimony.

“Sec. 14. The sustained development of a reservoir of national talents consisting of Filipino scientists, entrepreneurs, professionals, managers, high-level technical manpower and skilled workers and craftsmen in all fields shall be promoted by the State. The State shall encourage appropriate technology and regulate its transfer for the National benefit.”

As a senator, Ka Blas was very vocal against moves to change the Charter for short-term vested interests that would favor a powerful few. “The Constitution shall always represent the tension between freedom and order. We must be prepared to live with this tension. For order without freedom is unimaginable, and freedom without order is sheer anarchy and barbarism.”

Any changes in the Constitution, he said, must be done within its ambit, following the legal processes, and with the full support of the Filipino people.

SENATOR-JOURNALIST

“Toots, ano ba balak nilang sulatin? [Toots, what are they planning to write about?]” This was the question that my father, at that time a senator, would ask me, given my role as media relations officer. I would then rattle off the news summaries of reporters covering the Senate. The next morning, Ka Blas would reach for his cup of coffee and the newspapers piled up on his bedside table. He would then comment on which reporter got the news angle right, from the perspective of this senator-journalist/editor.

It was during his Senate years that Ka Blas would delight in the company of young journalists, perhaps remembering his own deskman days in the Daily Mirror. He knew them all by their first names, and it didn’t matter what size of readership or viewership their media establishment had. For the senator-journalist, it was the profession that was sacred and every reporter was to be treated equally and fairly.

Every Friday, Senator Ernesto “Boy” Herrera and Senator Ople would team up for a regular press conference. My job was to generate press releases that would pass his keen eye for public policy combined with grammatically correct, coherent news releases. We had a stapler ready, and a table of contents on top of press releases on a variety of topics. At that time, press releases were handed out, analog-style.

Joey Salgado, formerly of Malaya, who served as media bureau chief of the Office of Senator Ople, had this to say:

“Ka Blas never needed a ghostwriter. The hardest part of my job as a press release writer was putting words in Ka Blas’s mouth, stringing words together that I thought were close approximations of the Ka Blas style of speaking and writing. In truth, these were poor copies. One time I thought I had a press release, complete with quotes, down pat. I was already clutching several copies for distribution to the Senate press when I showed the press release to Ka Blas at the Session Hall. Ka Blas read the story, and somewhere between the fourth and fifth paragraph, he took out his pen. Without missing a beat he went to work on the story, swishing his pen on the paper and making those editing marks familiar to any newsman. I stood frozen at his side, mentally knocking myself on the head for thinking I could pass myself off as Ka Blas Jr. After what seemed like an eternity for me…Ka Blas reread the story and was obviously satisfied. He put the cap back on his pen, and, with a smile, handed me the newly mangled, but much improved, press release.”

Senator Ople was first elected senator for a six-year term in 1992. He was re-elected in May 1998 for a second, and with the term limits in the Constitution, his final term. In his ten years in the Senate (1992-2002), he was chairman of the Senate committee on foreign relations and the civil service and reorganization committee. He was elected Senate President Pro Tempore in 1998 and his peers elected him Senate President in the middle of 1999.

As chair of the Senate foreign relations committee, he led the ratification of 110 international and bilateral treaties. Among those vital international agreements were the RP-US Visiting Forces Agreement, an instrument that strengthened the PH-US security alliance.

He sponsored—together with Senator Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo—the ratification of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Uruguay Round creating the World Trade Organization. He also supported key ILO Conventions on child labor, conditions of work, and several others.

Among the key laws sponsored by Senator Ople were: Anti-Sexual Harassment Law, Migrant Workers’ Act of 1995, the Passport Act, the Flag and Heraldic Code of the Philippines, the first ever Salary Standardization Act, amendments to the Philippine Foreign Service Act, and several others.

During his acceptance speech as Senate President, Ka Blas said:

“At moments like this, I feel a compulsive tug of the heart pointing me back to my origins. I think of a barefoot little boy growing up in a humble nipa hut on the banks of the Hagonoy River, daring to dream of going to school and of finding the light in a strange new world of books in a new age of enlightenment. It was the beginning of a journey that has brought me to countless hardships and challenges and finally to the pinnacle of the Senate presidency, one of the highest offices within the gift of the Filipino people that you have bestowed on me today. It is an awesome miracle that I have experienced in my life, which I can only attribute not to any inborn or acquired merits of my own but to the grace of God, whose name I praise without end.”

DREAM COME TRUE: BEING FOREIGN AFFAIRS SECRETARY

As senator of the Republic, Ka Blas had a second term to finish, from 1998 to 2004. Fate intervened when President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo had a falling out with then Vice-President and concurrent Foreign Affairs Secretary Teofisto Guingona after the latter disagreed with the plan to allow US American troops to assist the government in running after the terrorist group known as the Abu Sayyaf. It was a difficult decision to leave the Senate but the new career path was irresistible to a keen observer of global events such as Ka Blas.

In July 2022, President Arroyo appointed Ople, as Guingona’s replacement at the DFA, despite Ka Blas being part of the opposition bloc in the Senate.

He had only one request that he conveyed to President Arroyo— that they would have exclusive meetings, one-on-one, to discuss foreign policy and DFA concerns. It was a wish instantly granted and consistently carried out. It was because of these meetings that no one can fault the Arroyo Administration of discordant voices in the foreign affairs sphere.

Despite his age, Ka Blas proved to be a hard worker, often being the last to leave the building, to ensure that international commitments, good relations with countries near or far, as well as OFW protection as the third pillar of foreign policy were assiduously carried out.

Secretary Ople as DFA chief also hosted weekly press conferences, and diplomatic briefings to make foreign policy accessible to publics, foreign and domestic. When there were terror threats directed at foreign embassies in Manila, Ka Blas wasted no time in assembling timely information from the appropriate agencies to assure diplomats assigned to the country that all efforts are being done to ensure their protection.

He was on top of every crisis involving our OFWs. In fact, the first act that he did upon assuming the DFA post was to convene a strategic management workshop where he outlined the protection of migrant workers as one of his priorities.

In a small, private meeting of senior DFA officials, Secretary Ople made it clear that he would not countenance any act by an embassy officer to talk down or insult or belittle the dignity and honor of Filipino domestic workers and all OFWs.

With his protégé, Patricia Sto. Tomas as labor secretary, the DFA chief made sure that there was smooth relations between the two departments. Secretary Tomas spoke directly to her former boss whenever concerns arose, that would have strained the relationship of their people on the ground.

Of foreign policy, Ople, the columnist of Manila Bulletin who also happened to be the DFA chief wrote: Foreign policy has about it an air of mystification that it does not deserve. This is not a special province of arcane knowledge that only a few experts are able to grasp. Our policies in international affairs should grow out of our own fundamental concerns and the vital interests of the Filipino people. And yet, not a few observers have remarked on the incorrigibly parochial cast of Philippine politics. They say Manila is an even more insular place than Jakarta or Kuala Lumpur.

It was his dream and part of his mandate to develop a wider constituency for foreign affairs in the country. He also wanted foreign policy to pave the way for a more inclusive society, embracing the cultures not only of the people of Luzon and the Visayas, but more so of the residents of Muslim Mindanao.

“In international affairs, Muslim Mindanao ought to be our strong, positive link to the Islam world which today consists of 46 states, anchored in the Middle East by the countries endowed with the largest known reserves of oil. Filipinos should not forget that the Muslims are a minority in the Philippines, but the majority in Southeast Asia.”

On December 14, 2003, Secretary Blas Ople boarded a plane that would take him from Tokyo, Japan where he attended a summit with President Arroyo, to Bahrain where a state visit was scheduled to take place in a few days. Learning that her DFA chief was already nursing a fever, President Arroyo advised Ka Blas to just go back to Manila and take a well-deserved rest. The 75-year old Cabinet Secretary chose to do otherwise, feeling that his mission to ensure a smooth state visit could not wait. While the plane was airborne, Ka Blas suffered a heart attack, and could not be revived. The plane made an emergency landing in Taipei, but by then it was too late. The accolades that followed Ka Blas’s passing were unprecedented as people from all walks of life remembered the patriotism, integrity and intellectual prowess of the humble son of Hagonoy, Bulacan.

And here we are, 18 years after his death, still longing for Ka Blas, or someone approximating his brilliance, to bring statesmanship back to life, while making sense of the world we live in, as only this son of a boat repairman and sari-sari store owner could.

In his speech before the students of Manila Law College in 1983, Ka Blas said: “The world plays a premium not for occasional flashes of brilliance but for sustained commitments to the performance of tasks.”

Ka Blas was consistent in his brilliance, whatever the task was assigned to him, because in his heart, there is no greater calling than that of public service.