It was Estrella who emancipated me, who liberated me…I used to be a very uptight, closed person.—Francisco Arcellana (Fernandez and Alegre, Writers and Their Milieu, 1987; 2017)

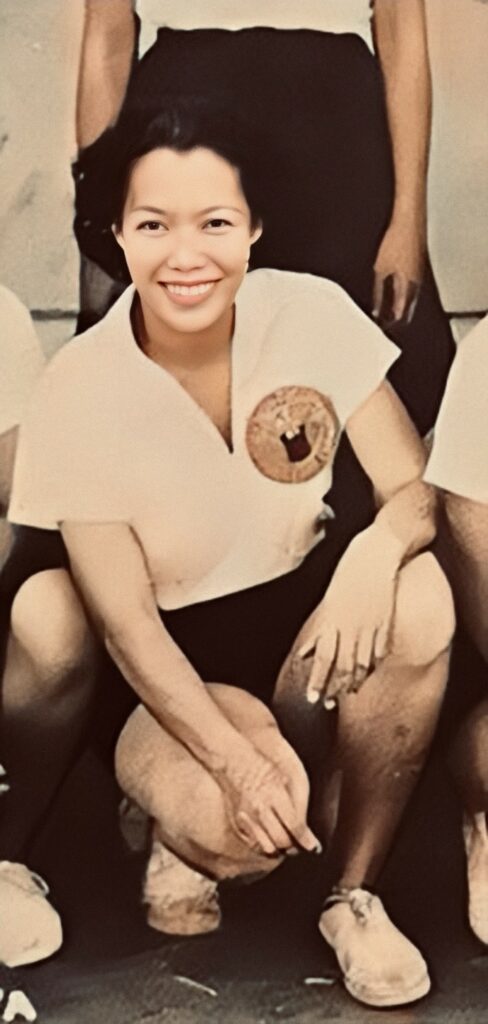

Estrella Alfon was perhaps, for many years, one of the most compelling figures in Philippine Literature. Kerima Polotan Tuvera lauded her “as the prolific writer of the prewar period.”

Alfon was the only female member of the Veronicans, a group of 13 avant-garde writers of the 1930s who rebelled against traditional forms and themes in Philippine literature. She was regarded as their muse.

Armed with an Associate in Arts from the University of the Philippines (UP), she was the only one who lacked academic training, “yet she earned an enviable reputation,” said literary scholar Edna Zapanta Manlapaz in her essay “Literature in English by Filipino Women (Feminist Studies, Spring 2000).

Celebrated as a fictionist, playwright, journalist, and public relations practitioner, Alfon was 66 when her death on December 28, 1983, headlined every newspaper in the country.

Alfon was a juror during the 1983 Metro Manila Film Festival when she died during the awards night.

In an interview with Doreen Gamboa Fernandez and Edilberto Alegre (1985), National Artist for Literature Franz Arcellana said that Alfon argued with National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin over a film. Alfon gushed over a movie that Joaquin dismissed as “trash.” Suddenly, Alfon collapsed due to heart failure, which Arcellana believed was triggered by asthma.

Days before that year’s award ceremonies, critics foreshadowed a sweep of films directed by future National Artists Lino Brocka and Marilou Diaz-Abaya. Brocka’s noir crime Hot Property starred Carmi Martin, Tony Santos Sr., Philip Salvador, and Dennis Roldan (celebrity siblings Marco and Michelle Gumabao’s dad). Diaz-Abaya’s historical drama Karnal featured a cast of acting heavyweights that included Charito Solis, Vic Silayan, Joel Torre, and Philip Salvador, with newcomer Cecile Castillo in the lead.

Critic Joee Guilas noted that many were shocked after Pasig Mayor Vico Sotto’s mom Coney Reyes won the Festival Best Actress award for the movie Bago Kumalat ang Kamandag. Character actress Alicia Alonzo’s younger sibling, action star Anthony was given the Best Actor award for the same movie. Willie Milan was named Best Director.

My instinct told me Alfon was perhaps fighting for Diaz-Abaya’s Karnal, exceptionally narrated by two-time Asian Film Festival Best Actress Solis. The movie was set during the 1930s, during the American colonial period. It tackled rape, incest, parricide, and tyranny in the small-town Philippines with a solid feminist subject-position, themes that Alfon herself advocated with so much energy in stories like “English” (1936), “Servant Girl” (1937), “O Perfect Day” (1937), “Dear Esmeralda” (1940), and “Magnificence” (1960).

Arcellana said that during Alfon’s necrological rites at the National Press Club, Joaquin would say something and then go back behind the leaves. “He would be crying because he felt awful.”

BEGINNINGS

Officially, Alfon’s literary career began with the Philippine Graphic. In an interview with Roger Bresnahan, celebrated American critic of Philippine literature in English, at the Manila Press Club (1980), Alfon remembered:

“My mother sent my school themes to a literary contest in Graphic. And of course, I won…For a Cebuana girl to be in a Manila paper, that was something! The next mail brought me two pesos as prize for this weekly contest. I was so happy! Two pesos to spend! This was before 1930, so you can imagine how much money that was then. And then the monthly competition I again won! They paid me ten pesos, so I said, ‘This is the profession for me.’”

From then on, Alfon’s career thrived from the 1930s to the late 50s. Unable to complete a pre-medical course at the University of the Philippines because of poor health, she was determined to pursue her writing more vigorously.

Her first story, “Grey Confetti” (1935), was quickly followed by many others. She regularly

contributed to weekly Sunday magazines and had several stories cited in Jose Garcia Villa’s annual honor rolls. A collection of her early short stories, “Dear Esmeralda,” won the Honorable Mention in the Commonwealth Literary Awards derby (1940).

“We used to lie around the UP campus on Padre Faura, and it would be our exercise for someone to say, ‘Oh, look up at the cloud. Let’s write about it….’ There were the things that made the Veronicans. We used to go to the circus. We used to go to the zoo. We would go to Intramuros, where there were promenade places. You could walk along the walls because they were eight feet wide. Ocampo, Arcellana, N.V.M. Gonzalez.”

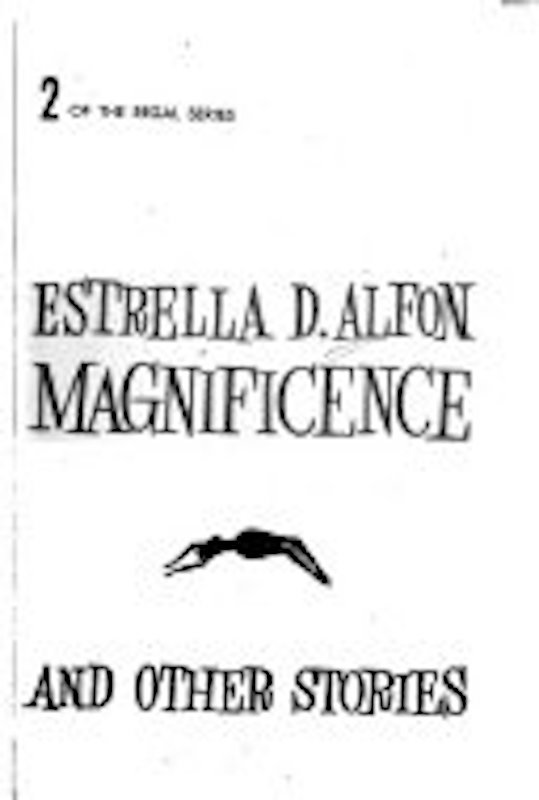

Alfon collected 17 of her stories in Magnificence and Other Stories (Manila: Regal Printing Company, 1960). Of these stories, Francisco Arcellana said, “When I say that these stories are powerful as stories, I mean they are compelling. They are told with urgency. They make you think of the ancient mariner.”

UNMATCHED INTENSITY

According to Professor Thelma Engage Arambulo, former chair of the Department of English and Comparative Literature, UP Diliman, Alfon’s fictional world is defined by family relationships: between parents (especially the mother) and children, women and lovers, wife and husband, women and their female friends. Where Alfon explores the mother-child relationship, her stories become most powerful and intriguing.

For Arambulo, “Magnificence” is unmatched for its quiet intensity and ability to stop short of spelling out its potential horrors. The mother grows more significant than life. “Anguish” explores the notion of contamination, not just leprosy, as do several other stories about children paying for their father’s sins. Arambulo added that perhaps because Alfon lived in Compostela, where the leprosarium used to be situated, the common fear of contamination frequently surfaces in her stories. But it is not just leprosy. It is, at times, licentious men infecting their wives’ and children’s lives; war conceived and fought by men infecting domestic life, separating wives from husbands, fathers from children, sisters from brothers, mothers from sons; small-town moral values alienating young people.

“Yes, In Cebu. It was a small street…It ended in a church, it started on a bridge. And if you shouted loud enough from the bridge, you could be heard in church. And I knew every one of those people in every one of those houses, from the time I was very young to the time I had to leave Cebu…It could never be rebuilt again. It’s now a squatter area….”

For critic Donn V. Heart of Syracuse University and Northern Illinois University, Alfon’s collection of 17 short stories reflects “the author’s statement that she does not make up her stories but merely tells them. In a review that appeared in Pacific Affairs (Spring 1962), Hart singled out Alfon’s “Servant Girl,” who suffers the beatings of her drunken mistress in hopes her lover may return, the young man with leprosy who hacks off his infected finger, and the city girl who returns to the village that is diffused with a Rousseau-like aura of peace and quiet. Hart also noted that several stories in Alfon’s collection were situated in Cebu during the Second World War.

Not fully aware of what National Artist for Literature Gemino H. Abad described as “Literature from English,” Hart felt that Alfon’s stories lack “the sophisticated polish and symbolism characteristic of Brillantes’ tales, but they add to anyone’s understanding of contemporary Filipino society.”

But Arcellana, in his introduction to Magnificence and Other Stories, writes, “These stories have been lived. They were lived first before they were told and written.”

CONTROVERSY

By the 1960s, Alfon wrote more plays, many Palanca-winning, but concentrated mainly on public relations and journalism. Between 1960 and 1979, Alfon published only four more stories. Arcellana attributed this to “Fairy Tale for the City,” a powerful Alfon story that became a litigation subject. The uber-conservative “Catholic League of the Philippines” charged Alfon with obscenity. Though convicted, she was given a presidential pardon by President Carlos P. Garcia in 1957.

The Ateneo Library of Women’s Writings (ALIWW) pointed out that while critics found cause to commend her, Alfon’s controversial narrative about a young man’s initiation into sex was essentialized as pornography. In recent years, several students in my creative writing and literature classes read “Fairy Tale for the City” as the author’s paean to Quiapo as Old Manila, quite foreshadowing the movement of the metropolitan center towards Makati, and yes, even the BGC for the years to come.

At the height of its controversy, Arcellana said that many writers and artists appeared to have championed Alfon. But during the actual litigation proceedings, only Arcellana, NVM Gonzalez, and a handful of mostly UP writers appeared and testified on Alfon’s behalf. Public opinion during that time was mixed. In the years to come, Alfon’s experience became a model for many landmark cases that challenged intersections of art vis-à-vis aberrations to conventional thinking.

…it didn’t wear me down but wore my witnesses down. Some days I was there in court all by myself. And I think I had a very inexperienced lawyer…But the editors of the papers. Their wives were members of the Catholic Women’s League…there was nothing in the story that could be called obscene. There was only that word, “breast.”

Quite a few would remember that years after Alfon’s altercation with the law, actress Tetchie Agbayani posed nude for the German edition of Playboy. She was sued for obscenity by morality crusader Polly Cayetano. The case was dismissed. National Artist for Film Ishmael Bernal’s Manila By Night (1980) became City After Dark after moralists and politicians rallied against the use of “Manila” in the original title, and the film’s “celebration” of the “low life” of people gravitating around Malate, then known as Manila’s party district, during the late 1970s.

Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB) Chair Nicanor Tiongson, UP Professor Emeritus for Film, resigned after Jose Javier Reyes’ Toro (2000), retitled Live Show, was pulled out of cinemas in March 2001.

Tiongson’s decision to publicly exhibit the film was loudly opposed by the Roman Catholic Church under the late Jaime Cardinal Sin. President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo promptly ordered that the film be pulled out of cinemas, eventually deciding to ban it altogether after a review. While these cases reached stratospheric proportions, Alfon predated paradoxical discussions on queer love, drugs, exotic dancing, domestic abuse, broken promises, and prostitution. Reading Alfon, these controversial topics are real-life issues and should be depicted boldly, sensibly, and with conviction.

ALFON’S PLAYS

Ironically, while Alfon is primarily acknowledged as a pioneering short fiction writer, she received more literary awards as a playwright. She received Palanca Awards for One-act Play in English for “Forever Witches” (1959), “With Patches of Many Hues” (1962), “Tubig” (1963), and “Knitting Straw” (1968).

“The White Dress” (1974), an underrated work, garnered Alfon her only Palanca for the short story. She received the first-ever National Fellowship for Fiction from the UP Creative Writing Center.

In addition, her one-act plays “Losers Keepers,” “Strangers,” “Rice,” and “Beggar” swept all prizes in the Arena Theatre Playwriting Competition. The Philippine Normal College (renamed Philippine Normal University) sponsored the competition, organized by National Artist for Theatre Severino Montano, then Philippine Normal College’s Dean of Instruction.

Rolando Tinio’s essay “Retracing Old Grounds: The Paradox of Philippine Theatre” (1967) identified Alfon and her Arena playwriting contemporaries, among them Antonio Bayot, Alberto Florentino, Wilfrido Nolledo, Jesus T. Peralta, and Mar Puatu.

Sadly, her plays are no longer staged today. And yet, all is not lost for Estrella Alfon. There is a continuing interest in her and her works among generations of academics.

In her later years, Alfon enjoyed the company of writers in national workshops. In particular, she enjoyed the Silliman National Writers’ Workshop in Dumaguete “because Ed and Edith Tiempo are old friends.” She confides to Bresnahan (July 14, 1980):

It wasn’t so much the writing I loved as the chance to make metaphysical contact with Edith Tiempo’s mind. She’s very into meditation and ESP. And when we were out of the classrooms and were at the back of her house, which is a beautiful place, we would commune with spirits that Edith said were there.

At the University of Santo Tomas and UP Diliman, Professor Emerita Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo teaches the literary tradition of the essay and the nonfiction narrative in the Philippines. While touching on the American colonial period, Hidalgo frequently highlighted the contributions of Alfon and her contemporaries, among them—Arcellana, Jorge Bocobo, Francisco Icasiano, Carlos P. Romulo, Arturo Rotor, and Vidal Tan.

STORYTELLER

At the height of New Criticism that pervaded universities here and overseas, several scholars may have lamented the seeming “formlessness” that violated all the rules of the critical school. UP Professor of Comparative Literature Dolores Stephens Feria argued that Alfon’s academic commitments were “instinctive rather than calculated.”

In response, Alfon admitted that she writes, “the way I feel—I’m a Cebuana. I cannot write in Tagalog. I cannot speak it. I cannot understand it.” Alfon insists that she writes in English because “I can express me better in English.” Alfon writes as a Cebuana, not as some Anglo clone. “We do employ native idioms and colloquialisms,” she says. For Alfon, the dialect is in her ear. “I am not a story-writer. I’m just a storyteller. I never really studied writing.”

Despite her lack of academic rigor, Alfon became a popular subject in theses and dissertations across the country. With critic Dr. Isagani R. Cruz as an adviser, Herminia Santos Bas worked on a dissertation at De La Salle University entitled “The life and works of Estrella D. Alfon: A Critical Edition” (1995). Santos Bas compiled Alfon’s short stories, six plays, and 13 essays. She also presented an extensive literary biography and critically assessed Alfon’s works.

Santos Bas deserves commendation for preparing an exhaustive enumerative and descriptive bibliographies of Alfon’s existing works. The pieces have also been annotated by stating the data on publications, translations of Cebuano expressions, and definitions or explanations of some terms used. The dissertation made significant recommendations to help ease the job of the literary critic or historian.

“Alfon’s contribution to the growth of Philippine literature bespeaks of the country’s heritage. Therefore, as a representative of the Filipino women writers, she should be accorded due recognition,” added Santos Bas.

In UP Diliman, Francis Eduard Llamas Ang is working on his MA Comparative Literature thesis focusing on how Alfon’s stories may create a connection between emotions and social class in their depictions of interclass relations and encounters.

SOCIAL CLASS, SOCIAL REALITIES

While lamenting a general lack of writing on Alfon’s work, Ang’s ongoing research project on “Emotions and social class in the short stories of Estrella Alfon” has updated the coverage of Santos Bas’s dissertation with a review of related literature on Alfon’s life, works, and writings, with most of the existing scholarship in the form of unpublished theses.

Ang also noted that the little scholarship out there is generally lacking in diversity, with most critiques and analyses focusing on the feminist or formalist aspect of her work with occasional input from linguistics and structuralism.

What is interesting in Ang’s ongoing project is that he will try to determine the extent Alfon’s stories have already been discussed on an emotional level by literary and cultural infrastructures.

He will also examine how social class plays a role in Alfon’s short stories, exploring the social type of the characters involved and how these might affect the particular social situation. He will also understand how Alfon’s characters might interact with one another given their class backgrounds and inequalities.

For Ang, a clearer understanding of the dynamics of social classes is integral to our experience of emotions in Alfon’s stories. Considering that emotions are often conceived of as reactions to a situation or circumstance, it is essential to consider how scenarios are defined by the social class backgrounds of those involved in them.

As a millennial and a scholar of Philippine Literature from the regions, Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT) Center for Culture and Arts head Amado Cabus Guinto sees Estrella Alfon as a beacon of hope for those who write for and about the countryside or the margins so to speak. Long have the writers from the regions been given fewer chances to be mainstreamed as there has been a shortage of publication opportunities for them despite their talent. But Alfon is the best example that writers writing Truth about life outside Manila can make it.

For Guinto, Alfon’s writing resonates even with today’s generation because her works are rife with realities not different from those in the center but are unique enough for us to understand the pains and joy patently Cebuano. One can see these, especially in the story “Magnificence,” which speaks about how fierce a woman can become in protecting her children from predators, and “Servant Girl,” whose theme revolves around the ordinary person’s ambitions to get out of the muck but is still unrewarded because fate is simply cruel.

Meanwhile, National University of Singapore Ph.D. scholar Francis Luis Torres believes Alfon’s effect and influence on his generation have been impactful and far-reaching with her story.

On the one hand, she has become a Cebuana trailblazer because her stories masterfully encapsulate daring and intense feminist realities when men dominate much of Cebuano society. Her words have also inspired a generation of Cebuano girls and female writers to speak out their lived truths.

On the other hand, her words bring forth characters and settings that beautifully reflect the Cebuano’s sensibilities and realities. She never fails to find the “Magnificence” of the banal and risqué, which gives life to stories frequently ignored or marginalized by the literary canon. Honestly, her contributions continue to Cebuano (and Philippine) literature that resonates until the present. Her works are, indeed, timely and timeless.

Arambulo observes that Alfon’s fictional world is essentially a world of women and children, elements traditionally marginalized by literary criticism. The female protagonists in Alfon’s stories range from the madwoman on the steeple who blames God for her stillborn baby to the ignorant servant girl who clings to her romantic notions of an ideal man; from the magnificent mother who saves her daughter from a sexual pervert to an Espeleta woman on whom the gods choose to pour down one misfortune after the other.

For these representations of women in her writings, whether they are perceived as victims in that they are treated more as objects rather than as subjects, Alfon deserves to be reclaimed, retrieved, and remembered.

Added Arambulo: “The cultural tradition of male domination has fostered the distinction between male as subject (superior, active agent) and female as an object (inferior, passive object of man’s action and intention), a distinction which has been accepted as part of the natural, even divine, order by most men and women.” Alfon made readers and pundits think that while some women measured themselves in their acceptability to men, women overtly do not question such notions’ validity. They take comfort in the idea of women and men complementing each other; it is seen as a form of equality.

WRITER, WOMAN

Posthumously, the feminist issue of Ani, the literary journal of the Cultural Center of the Philippines, edited by poet Marjorie M. Evasco (1988), was dedicated to Alfon as a “writer, mother, sister, friend.”

The 18th UP National Writers’ Workshop at Kalayaan Residence Hall, UP Diliman, was dedicated to Alfon, with the theme “Si Eva sa Panulat.” The workshop fellows that year included exceptionally gifted Filipina writers Nerissa Balce, Merlinda Bobis, Noelle de Jesus, Caroline Hau, Maningning Miclat, and Dinah T. Roma. During that year’s workshop, other writing fellows were Jim Pascual Agustin, Roberto Anonuevo, Ed Cabagnot, Fidelito Cortes, Teddy Espela, Manuel Muhi, the current President of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP); Roland Fulleros Santos, Joel H. Vega, and this writer.

Novelist Lina Espina-Moore, Alfon’s long-time friend and kababayan, also released The Collected Stories of Estrella Alfon (Giraffe Books, 1994). Estrella Alfon would have been pleased.

On its website, Ateneo de Manila University’s ALIWW reported that Alfon was the most prolific Filipino woman writer before the war, but she “was at times charged with sloppy writing and suspected of writing for money. Undeterred, she continued to write not just more stories and journalistic pieces but also plays.”

Ricaredo Demetillo described Alfon as one of the writers “treated with respect.” Herbert Schneider, S. J. says that Estrella Alfon’s stories deal with the people of the lower middle class. For Zapanta-Manlapaz, she was the only one who lacked academic training, yet she earned an enviable reputation. Poet-critic Ophelia Alcantara Dimalanta sees Alfon as one who “began her writing career as early as before the war but whose literary career was more pursued more seriously after the war.” Arambulo commended the intensely autobiographical elements in Alfon’s works, especially in the Espeleta stories, that produced “straight from the heart” effects that make her fiction much more personal and intimate.

Meanwhile, Arcellana believed Alfon’s stories “are some of the most powerful ever written by a Filipino.” Revaluating Alfon, National Artist for Literature Cirilo F. Bautista underscores Alfon as “a feminist before the term gained currency in our milieu…she knew she could make her job more effective by writing with subtlety and honesty. Because of that, she was an artist of the first rank.”

While Estrella Alfon was various things to various persons, in the end, I subscribe more to what Polotan Tuvera had written about her, that she was of two essences: A writer and a woman.

It is impossible now to say where one ended, and the other began, for she went at being

both—instead, she brought to both pursuits an incredible passion that is not given to all of us to possess. She has come far from San Nicolas, Pasil District in Cebu. And that, for me, is pure magnificence.