Sometime before Lope K. Santos passed away on May 1, 1963, he paid a visit to a cemetery with his wife, to the grave where he intended to have himself buried. He frowned on seeing how dark the grave was. He told his wife Simeona that upon his death, she should place a light in his tomb so that he could continue to read and write. According to the late Rogelio Mangahas, the episode seemed to dramatize Santos’s immortality as novelist, poet, and scholar of Philippine language and culture, and labor organizer.

As a politician, Santos served as Governor of Rizal from 1910 to 1913, Governor of Nueva Vizcaya from 1918 to 1920, and member of the Philippine Senate in 1920–1921 (just like his fellow writer and union organizer Isabelo de Los Reyes, who became a senator in 1922).

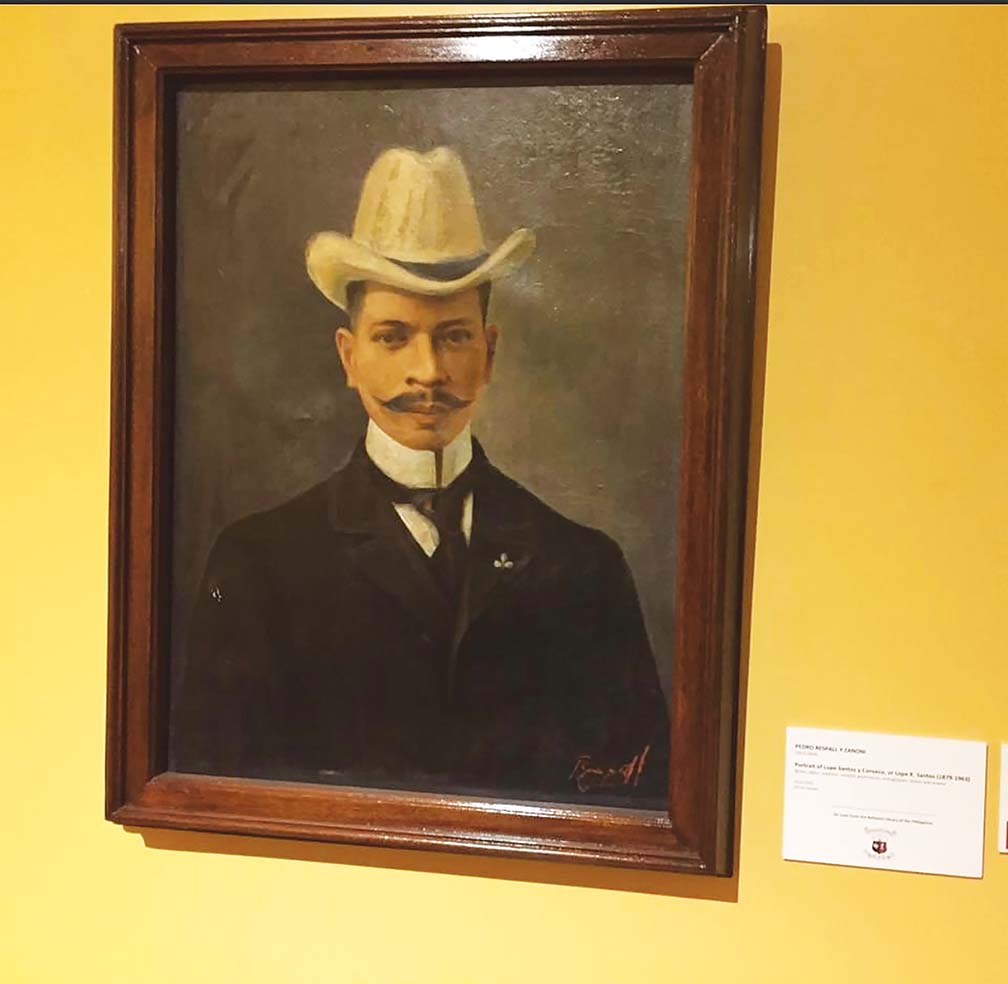

As a writer, Lope K. Santos held his own among equally illustrious contemporaries. One of his greatest achievements is his novel Banaag at Sikat. Santos began publishing chapters of his first novel in 1903 in the weekly magazine Muling Pagsilang. Santos completed the narrative series two years later in 1905, while he was still in his 20s. He published it as Banaag at Sikat in 1906 under McCollough & Co.

The novel was a love story set against the backdrop of the trade union movement. It quickly gained a reputation as historical and literary text. Historian Teodoro Agoncillo, included it in his list of most valuable books in Tagalog literature. He wrote that “Banaag at Sikat initiated a more skillful method of writing a novel. Thus, it is the first novel that cleared the way for other Tagalog novels.”

The novel’s influence goes beyond the realm of literature. According to poet and novelist Danton Remoto, “Banaag at Sikat is considered the fountainhead of social realism in the Tagalog novel. It starkly mirrored the various forces clashing during the early days of American colonialism; in this guise, the novel could be seen as a social text.”

The book, which was the first proletariat novel in Asia, enjoyed brisk sales. Remoto, quoting Agoncillo, notes how the book was “avidly read by the masses and intellectuals.” Just as Jose Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo had influenced many Filipinos in the fight against colonialism and exploitation, Banaag at Sikat “in no small measure influenced the workers in fighting for economic, social and political reforms. As a result, more and more labor unions sprouted; strikes were resorted to by the laborers, particularly those engaged in cigar and cigarette manufacture, to the discomfiture of the capitalists who had been accustomed to pushing the workers around.”

Who was Lope K. Santos and what is the story behind his widely influential novel? Santos was born on September 25, 1879, in Pasig, then a part of Provincia de Morong. His mother was Victoria Canseco from San Mateo (now a part of Rizal Province) while his father Ladislao Santos hailed from Ugong, Pasig. Ladislao Santos worked at a publishing house in Guipit, Sampalok, where the young Lope began his education at age 5.

Lope K. Santos studied education at the Escuela Normal Superior de Maestros for education and graduated from the Colegio Filipino. Much later, he enrolled at the Academia de la Jurisprudencia and would earn a Bachelor of Arts degree at the Escuela Derecho de Manila in 1912.

Lope used to write his name as “Lope C. Santos,” but when he started working, clerks for some reason kept misspelling his name as Lopez Santos. Lope then began signing his name as “Lope K. Santos.”

TUMULTUOUS TIMES

Lope K. Santos grew up in tumultuous times. During his childhood, the likes of Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, and many others protested abuses by the Spanish friars and the colonial government. Santos was 15 or 16 when Bonifacio launched the armed revolution against the Spanish colonial government in August 1896.

Santos was in his second year, studying at a school along Padre Faura, when he and his classmates heard the shots that killed Jose Rizal in Bagumbayan (Luneta Park) on Dec. 30, 1896. Many young people, the 17-year-old Santos included, joined the Katipunan to help free the Philippines from colonial rule. By June 1898, Philippine forces were able to take control of most of Luzon.

There is no doubt, according to Remoto, that Santos drew inspiration from his father, whom the Spanish government in the Philippines had imprisoned and tortured in Fort Santiago for owning copies of Noli Me Tangere and the Andres Bonifacio’s newspaper Kalayaan.

According to Lope K. Santos’s great grandson Rizalito Santos-Garcia, Ladislao was arrested by Spanish authorities and then taken to a Guadalupe seminary to be imprisoned and beaten. Ladislao died, possibly of pulmonary tuberculosis, before Lope K. Santos finished his second year in high school. After his father’s death, Lope K. Santos himself found work at a printing press.

His father’s experience is believed to have inspired one of the most moving chapters in Banaag at Sikat. Nieves Baens Santos noted that the chapter “Kayamanan ng Mahirap, Huling Bati ng isang Ama” depicted that last thoughts of a man with tuberculosis, “hovering between life and death, who left nothing except a humble name and poverty to his wife and seven children.”

Santos joined the armed struggle for national independence: first with the Philippine revolutionary forces against Spain, then with the Philippine forces in the Philippine-American War.

The December 1987 signing of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato peace treaty temporarily halted fighting between the Philippines and Spain. Santos worked as a guard at Intramuros under the Spaniards to make ends meet. When the Philippine-American war broke out or shortly before, instead of continuing to work for the Spanish government, he distributed food and firearms, possibly under General Pio del Pilar or General Licerio Geronimo.

Santos was among the Philippine soldiers who laid down their arms after American forces captured President Emilio Aguinaldo in March 1901.

On the suggestion of his mother, Santos courted Simeona Salazar from Paco. They married in February 1901 in a church on San Marcelino street in Paco. They would have three children, whom they named Luwalhati, Lakambini, and Makaaraw.

By this time, Santos had already taken up writing and publishing. He frequented the protest theater productions, and saw how American soldiers arrested the writers of these plays. Santos noted how these playwrights were deeply committed to taking part in the people’s struggles.

A PRIMER FOR LABORERS

At the turn of the century, workers were yet to be organized through trade unions. Employers kept wages low and subjected laborers to all sorts of harsh, inhuman treatment. In response, Santos picked up ideas of socialism that came to the Philippines by way of Spain, according to National Arist for Literature Bienvenido Lumbera. When Santos became involved in labor organizing, he began writing Banaag at Sikat “with the expressed intent of introducing Filipino laborers to socialism, Santos’ interpretation of the struggle between labor and capital in the Philippines of his time.”

The novel, Lumbera wrote, “is an ambitious work that tries to be a primer for laborers as well as about a society undergoing transition from agricultural economy to industrialization and emerging from the dark superstition and fatalism into the light of science and hope.” The novel, through Santos’s keen observations and satirical wit, succeeds in “exposing the greed and corruption of the ruling class.”

Poet and essayist E. San Juan, wrote that “[w]hile [Santos] was leading the workers

in the city and attacking the feudal landlords in the countryside, Santos composed his

masterpiece, Banaag at Sikat.”

Banaag at Sikat, which was considered the “first socialist-oriented book in the Philippines… expounded principles of socialism and [sought] labor reforms from the government.” It is credited for the inspiring the causes of the Socialist Party of the Philippines, formed in 1932, and the Hukbong Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon, formed to resist the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in the 1940s. The novel has also been called the first Filipino proletariat novel and the first Filipino anarcho-syndicalist novel.

The labor movement grew as the first decade of the 1900s progressed. Santos continued to study books on socialism and other new ideas. His involvement in the labor movement further deepened his knowledge of social issues. He joined the Union Obrera Democratica Filipina (UOD), the first modern trade union in the Philippines. Its first president was Isabelo de los Reyes, who had brought home from Spain the works of socialist thinkers Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, and Karl Marx.

THE PHILIPPINES’ FIRST LABOR UNIONS

In History of the Philippine Labor Movement, author Dante G. Guevarra gives an account of the history of the UOD and the attacks it suffered under the American colonial government under Governor-General William H. Taft. In August 1902, the UOD organized a series of strikes to demand wage increases for workers from employers and a reduction of excessive work hours. Though some factories agreed to raise wages, by the middle of the month, the government would arrest de los Reyes and other leaders of the strike.

The American colonial government charged the union leaders for violating a Spanish anti-conspiracy law still in force that prohibited workers from asking for higher wages. De los Reyes was released four months later and pardoned on the condition that de los Reyes would desist from labor organizing.

Under de los Reyes’s successor Dr. Dominador Gomez, membership at the UOD continued to grow. But after one heated meeting with Taft, Gomez was subsequently branded a subversive and charged with “sedition and illegal association.” He was arrested under the orders of Taft in 1903.

Lope K. Santos organized the workers of the Katubusan Cigar and Cigarette Factory. Its slogan was “The whole product of labor for the benefit of workers.” In his publication Muling Pagsilang, Santos supported the idea of “the setting up of a common organization of workers and peasants to protest abuses of landlords and capitalists.”

After Gomez’s arrest, Santos became the last president of the UOD. Santos also organized the Union del Trabajo de Filipinas (UTF), which is considered the successor organization of UOD. For author Dante G. Guevarra, the UTF veered away from the spirit of unionism, observing Governor Taft’s influence on the UTF’s formation. The UTF, Guevarra wrote, was organized along the lines of the American Federation of Labor’s more conservative, arbitration-oriented setup. Guevarra calls this time a period of yellow unionism.

The UTF was eventually dissolved in 1907. Renato Constantino wrote that this dissolution was due to political rivalries within the UTF: since member organizations had begun supporting candidates in national elections, this split the UTF into warring camps, with some labor groups “deteriorating into mere adjuncts of political machines.”

The UOD and the UTF were the first labor federations in the country, according to Constantino. Santos and the leaders of these early groups saw in unionism a way to improve the living standards for workers. The labor movement endured under such leaders as Hermenegildo Cruz and Crisanto Evanglista. Constantino noted that as the labor movement progressed, labor unions and peasant mutual aid societies would evolve to become “radical organizations of class-conscious peasants and workers.”

At one point, Santos opened a school for laborers where he and Hermenigildo Cruz taught natural rights, socialism, and Marxism. (Some readers are convinced that the debates by Banaag at Sikat’s main protagonists were depictions of real-life exchanges between Santos and Cruz.)

It was through the efforts of organized labor that May 1 would be recognized as Labor Day. The day was declared an official holiday in the country in 1908 by the Philippine Assembly through Act No. 1818. Pressure from labor groups also resulted in the passage of the Employers’ Liability Act (Act No. 2473), a major milestone in the struggle to ensure safety and security of employees in the workplace.

DREAMS OF JOSE RIZAL

The printing house where his father Ladislao Santos worked played large a part in awakening in Lope K. Santos a desire to write. The young Ladislao took his son to work, where the young Lope read everything in sight, such as novenas, koridos, awits, komedyas, and other works in Tagalog. He also read the poems that his father wrote.

Ladislao himself wrote komedyas, which Lope would help his father stage. When Ladislao composed his plays, he would dictate the lines for his son to transcribe. During production, Lope held a copy of the script and gave cues to actors when they forget their lines. Lope began to develop his sensitivity to poetic language. He was around 9 years old.

One time, his father was setting to print a Tagalog poem entitled “Roberto y Diablo,” which was being published by Libreria Tagala, one of the bigger bookshops at the time. Similar awits were usually published with a tribute to the Virgin Mary or some other saint, but Lope noticed that the “Roberto y Diablo” manuscript did not have a prologue. So he composed eight or nine stanzas and added it to the poem as it was being typeset.

His father seemed to not have noticed the added pages, for he typeset Lope’s prologue along with the awit without any comment. Lope found it hard to admit the “mistake” to his father, in part because he thought that his verse might have been poorly written.

The publisher, Don Agustin Fernandez, arrived to check on the typeset copy and was puzzled by the new stanzas. “Islao, did you write this?” he asked. It turned out that Don Agustin remembered that the poem he was publishing did not have an introduction and so wrote one up himself in a rush. Ladislao and Don Agustin proceeded to compare the prologue he wrote and the one by Lope. Lope was afraid that he was going to be reprimanded.

Finally, Don Agustin said that he preferred Lope’s version. Lope was overjoyed to hear this, though he still could not gather the nerve to admit what he had done. The poem was eventually printed and sold with the additional stanzas that Lope had written.

Having forgotten many years later what he had written, Lope had hoped to find a copy of the poem so he could figure out what it was that could have convinced a veteran publisher to print those first verses Lope had composed on the sly. Lope K. Santos, in his old age, combed bookshops for a copy of “Roberto y Diablo” but was never able to find any.

For another book project, Ladislao was assigned to prepare the proofs for Gramatikang Tagalog by Father Mariano Sevilla. Lope would bring the proofs to and from Father Mariano’s house near the Administracion Civil near the entrance of Fort Santiago.

Lope began writing plays himself, though he later wrote that very few of his plays were worth staging. After the recent execution of Rizal, Lope was inspired to write one of his earliest plays, entitled Sueños de Rizal, which expounded on topics Rizal tackled in his works: the desire to free the Philippines from enslavement and foreign domination.

He showed the play to the theater manager of Datu Oriental along Cervantes road. The man liked the play immediately and offered to pay Santos 10 pesos for every staging. With the money he saved after four or five shows, Lope K. Santos was able to spend for his wedding with Simeona Salazar on February 10, 1901.

Lope also joined poetry jousts. Lope K. Santos recalled the opening of the duplo that he sometimes recited at these poetry debates:

Masanghayang plasang pinagtitipunan

Ng tanang doktores o tores sa tanan

Ang hiyas at ginto’t mutyang bagay-bagay,

Karbungko’t topasyo, brilyanteng makinang.

His poems “adhere[d] to conventional norms in meter and rhyme, in technique and substance,” which, E. San Juan wrote, was in contrast to “the analytic style and wide-ranging grasp of complex social forces shown in his fiction.” San Juan gave as examples such poems as Puso at Diwa (1913), Sino ka?. . . Ako’y Si… . (1946), Mga Hamak na Dakila (1950), and Ang Diwa ng mga Salawikain (1953).

But despite the poems’ “deceptive simplicity, [these] reveal an intense narrative vitality infusing the allegorical cast of his perceptions,” added San Juan. “In this lies the unquestioned merit of his poetic art. Santos’ writings as a whole illustrate the continuity in Tagalog literature of a realistic, critical but warm understanding of human problems and of the socio-historical contradictions in each man’s life. In this lies the enduring value of his works.”

Lilia Quindoza-Santiago counted Lope K. Santos among the notable poets who wrote during the American colonial period (1898 to 1946), along with Julian Cruz Balmaceda, Florentino Collantes, Pedro Gatmaitan, Jose Corazon de Jesus, Benigno Ramos, Inigo Ed. Regalado, Ildefonso Santos, Aniceto Silvestre, Emilio Mar. Antonio, Alejandro Abadilla and Teodoro Agoncillo. Santos’s epic poem Ang Panggingera (The Card Player, 1912), Quindoza-Santiago wrote, was “proof of how poets of the period have come to master the language to be able to translate it into effective poetry.”

Though Santos’s reputation as novelist overshadowed his other works, Lumbera believed that Santos’s achievements as poet needed to be reconsidered. Ang Pangginggera (which is more than twice the length of Florante at Laura) represented for Lumbera “Santos the poet at his best, combining in himself the robust outlook of a realistic novelist, the wry mockery of a mischievous satirist and the polish of a consummate craftsman.”.

MILITANT JOURNALIST

Having married Simeona Salazar, Santos needed to make sure he had the means to support a family. He turned to writing. Journalism was more than a way to make ends meet. It was a new and largely unexplored field, one in which Santos found an opportunity to further develop his craft as a writer and explore his many passions, especially as educator and patriot.

In 1900, he founded and edited La Luz and its sister publication Ang Kaliwanagan. The publications’ owners were masons, whom Santos got along with quite well. Santos also edited and wrote for Muling Pagsilang, which was the Tagalog edition of El Renacimiento.

He contributed to many other newspapers, including Ang Mithi, Kapatid ng Bayan, and the weekly lifestyle magazine Sampaguita. Santos wrote that, being a former revolutionary, it was through journalism that his militancy found continued expression.

However, then as now, journalists tended to find themselves the target of thin-skinned public officials. The interior secretary Dean C. Worcester forced El Renacimiento to shut down by successfully suing editor Teodoro M. Kalaw and publisher Martin Ocampo. Worcester felt that an unnamed corrupt American official—described in the essay “Aves de Rapiña” as having “the characteristics of the vulture, the owl and the vampire”—could only have referred to himself.

In Ang Kaliwanagan, using the pen name Sekretong Gala, Santos criticized American

occupation in the Philippines and the acts of cruelty committed by the American

forces against Filipinos. In his writings as journalist, Santos also wrote about events

in Samar, and killings in Mindanao.

Santos was called to report to the office of the provost under the American government. One official, Don Felipe Camino, summoned Santos many times to “remind” Santos that his writing about American rule made the government look bad, and questioned why Santos needed to praise the Liga Anti-Imperialista (likely referring to the American Anti-Imperialist League to which novelist Mark Twain belonged). Eventually, Santos wrote, the army ordered Ang Kaliwanagan to shut down.

In Talambuhay ni Lope K. Santos: Paham ng Wika, Santos wrote how Filipinos came to resent American officials for thwarting the struggle for independence. American officials, he wrote, merely came to replace the Spanish empire as the new lords of the Philippines. But despite attempts to silence writers like Santos, scholars, journalists, and fictionists would continue to examine issues of colonialism, capitalism, and the highly complicated relationship between the Philippines and the United States.

“FATHER OF FILIPINO GRAMMAR”

Santos was elected governor of the province of Rizal in 1910 (serving until 1913) under the Nacionalista Party, marking the start of his political career. He also became governor of Nueva Vizcaya (1918-1920), senator of the Philippines representing the 12th District (1920-1921).

When giving speeches, Santos would speak in Tagalog. While some of his contemporaries were more comfortable speaking in Spanish or English, they also grew to appreciate the value of speaking in the vernacular to better communicate matters of public policy. Friends and colleagues in politics, including Philippine presidents, would come to Santos to consult him about their speeches.

It was during this period that Santos began his campaign to establish a national language for the Philippines. Even after he ended his term as senator, Santos would continue to teach at Philippine universities, write, and develop his views on the promotion of a national language.

In 1940, Santos published Balarila ng Wikang Pambansa, which was the first grammar book on the national language. President Manuel Quezon appointed Santos as director of the Surian ng Wikang Pambansa in 1941, just months before the outbreak of World War II in the Philippines. He would serve in that position until 1946. He was also the first chair of the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino.

Because of his writing on Filipino grammar and on his campaign to develop a national language, Santos is sometimes referred to as the Father of Filipino Grammar.

While some critics described Santos as a purist when it came to grammar and vocabulary, Santos himself supported the idea of adapting and borrowing from various local and foreign languages. He offers a proviso, though: with some concepts as “health,” “sanitation,” and “moral,” native equivalents have been found and should be used. Otherwise, it would appear that these were never part of Filipinos’ lives, he said.

Santos was not under the illusion that adopting a national language would be an easy task. But it is necessary and possible, he said. “I believe that we must have a national language… It is being done in Indonesia and India. There is no reason why it cannot be doing here.”

RADIANCE AND SUNRISE

Paraluman Santos Aspillera was in Indonesia in late April 1963 as a guest of the Indonesia Women’s Congress, when she received a telegram with news of her father’s death. The sender was unknown and Aspillera had to wait for the next flight home before she could confirm whether the news was true or not.

Aspillera arrived on April 28 to condolences and flowers from friends of the family. But the stories of Lope K. Santos’s demise had been premature. She came home with Santos in bed, looking tired and weakened but still able to engage in conversation.

On May 1, 1963, on International Labor Day, Lope K. Santos passed away. He was 84. Condolences poured in from around the country. Senator and fellow playwright Francisco Soc Rodrigo paid tribute to Santos by calling him a true hero and a defender of workers and peasants.

Representative Jovito Salonga said, “It may have been just as well that he passed away on Labor Day, for he was a key organizer of the First Labor Congress in the Philippines 50 years ago.” International Labor Day was commemorated by the UDF as early as 1903 and recognized by the Philippine government in 1908.

On May 5, 1963, Santos was laid to rest at the Manila South Cemetery. Today, almost six decades later, his influence continues to be felt through his works. (Just last year, Santos graced the cover of Philippines Graphic along with Andres Bonifacio and other writers who took a critical look at class relations and analyzed the struggles of laborers in Philippine society.)

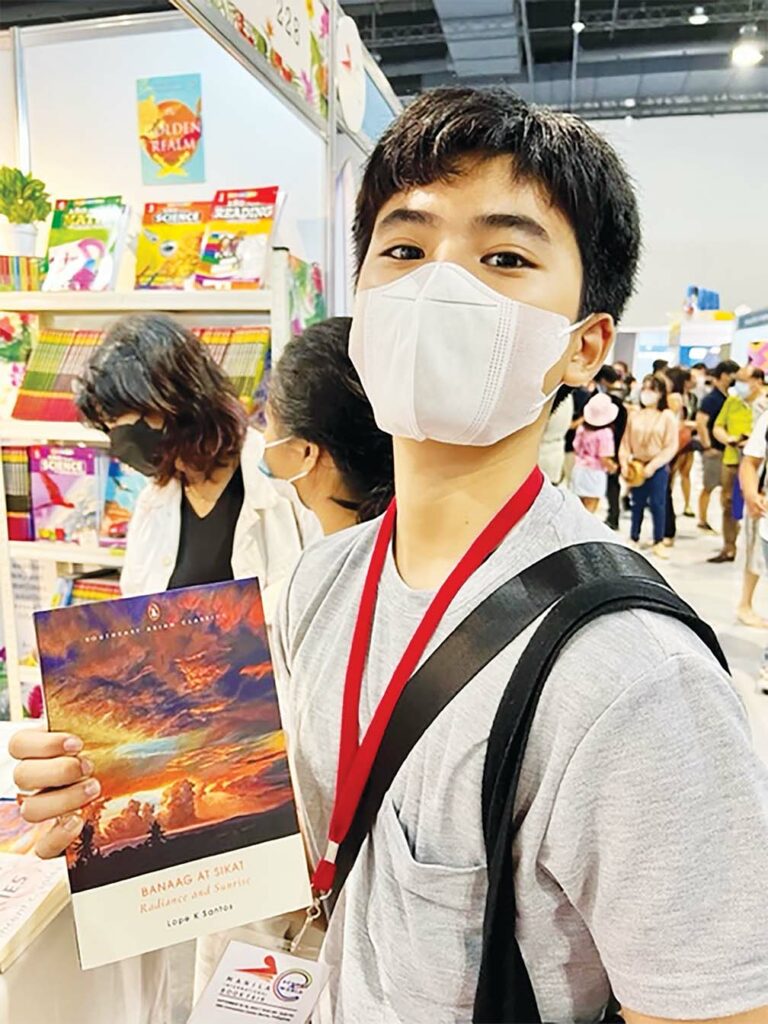

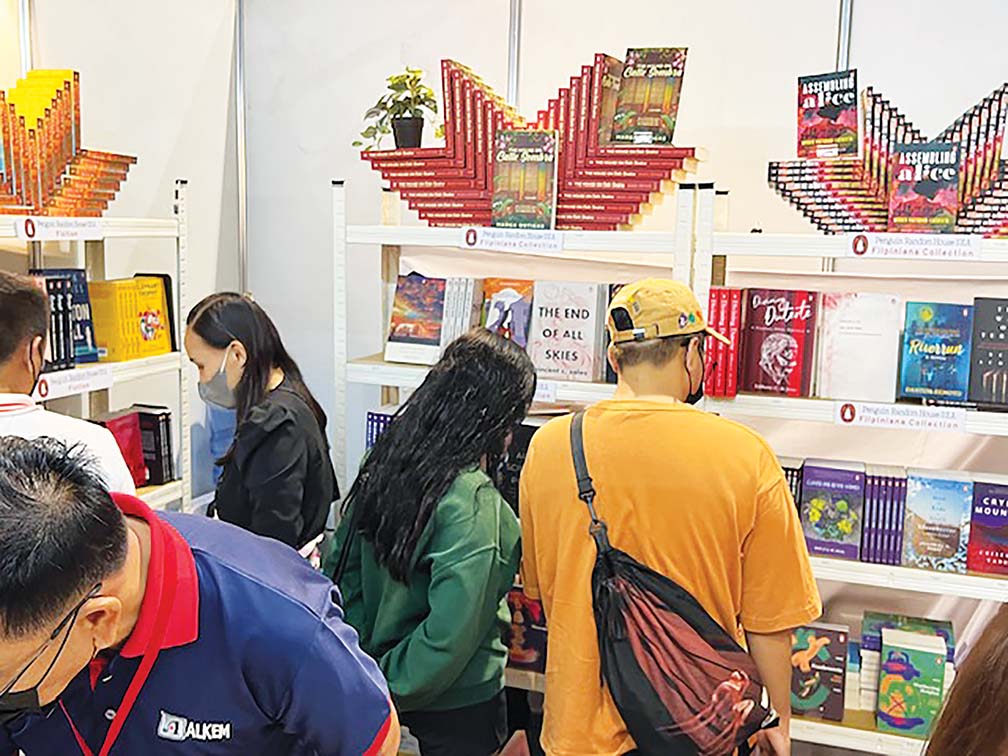

Banaag at Sikat has undergone numerous editions and translations. In December 2021, Penguin Books, under its Southeast Asian Classics line, came out with a handsome edition of the novel, masterfully translated into English by Danton Remoto as Radiance and Sunrise.

The novel demonstrates Santos’s belief that it is not enough that literature reflect what is happening. For Santos, literature should concern itself with how the world ought to be in light of the people’s aspirations.

LOLO LOPE ACCORDING TO HIS FAMILY

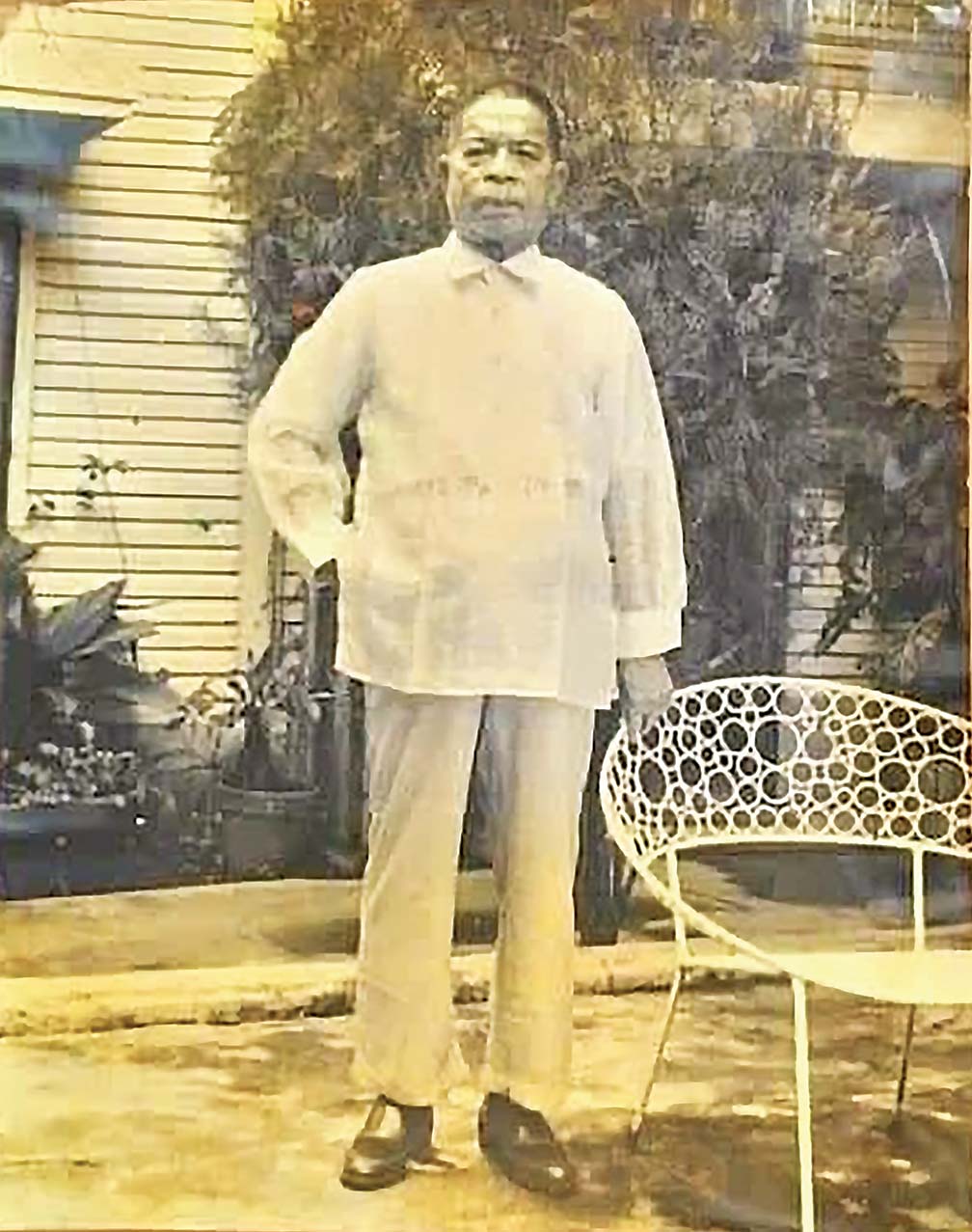

Lope K. Santos’s great grandson Rizalito Santos-Garcia, said his Lolo Lope shied away from parties and was not all that sociable. He lived a simple life, spending time in his private library or taking walks. He had no interest in living in mansions and driving around in cars.

He wore camisa chinos at home but would put on a barong Tagalog when he took walks around the neighborhood with his grandchildren or great grandchildren. He wore hats from Baliwag, Bulakan, and brought along a cane that he would use to wave away stray dogs that came too close.

His life and works have influenced family members, some who have worked as writers or found careers in book publishing and related fields. Vito C. Santos is author of the influential Vicassan’s Pilipino–English Dictionary. Paraluman Santos Aspillera, who prepared Lope K. Santos’s autobiography entitled Talambuhay ni Lope K. Santos: Paham ng Wika (1972), is the author of several books on Philippine grammar.

Rizalito Santos-Garcia remembers sleeping at his Lolo Lope’s library when he was in high school. Lolo Lope, first thing in the morning, would check up on his great grandson and give him 25 centavos as baon. At age 19, Santos-Garcia got his first job arranging books at Bookmark along Escolta. That was just the beginning. “I learned a lot from Lolo Lope and I knew early on that publishing and bookselling would become my life-long career.”

His great grandfather, Santos-Garcia added, was “a very patriotic man who loved his country to high heavens… He strongly valued honesty, sincerity, and love of country. Our Lolo Lope must be rolling in his grave knowing the kind of self-serving corrupt politicians we now have in government.”