As I turn 74 in December, I like to look back and sum up the modest journey of my life. I like to start where I was born.

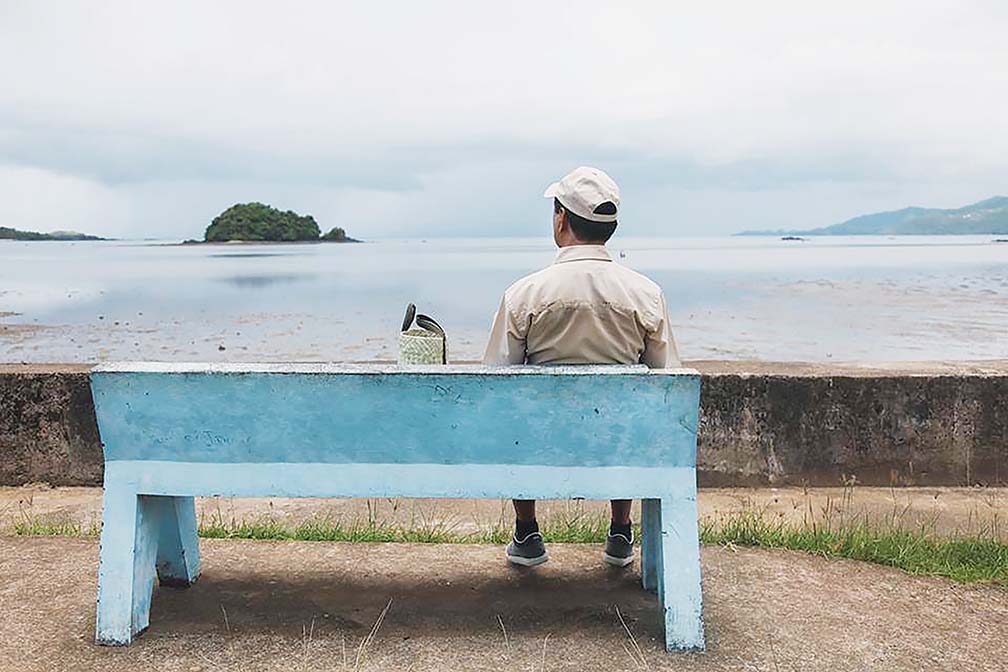

When I think of summer and early youth, my thoughts inevitably turn to the island of my birth in barrio Tilod in Baras, Catanduanes.

Where I was born, I think of the high bright sun of my coastal barrio where the river ends and the sea begins.

Westward down from the barrio chapel, I see the school where my mother used to teach. While my mother was busy with school chores, I was usually left in the care of a gentle old lady I called Lola Cayang and her daughter Tia Lily.

Growing up with them, I saw a second family I would seek out even as some of them would settle in Metro Manila. It was pure destiny that I found Tia Lily’s daughter on Facebook. Tia Lily has since moved on, and her daughter has settled in Canada.

So many memories of this barrio of my birth. Where the river begins is our mountain land, we call Sogod, and that part with the clearest stream I ever saw in my life we call Minacahon.

That’s where we used to take a bath, catch fresh shrimps and cook them with coconut milk with fresh pako (ferns). In the summer we would pick farm produce (corn, camote and other root crops) including abaca hemp from local farmhands.

For giving them free use of the land, we divided farm produce two-way. We transported our

share to the town proper by sea using a bamboo raft passing the shallow coastline.

A grade school classmate lived in Barrio Moning and come fiesta time, he would invite me to his place where all you could see were abandoned nipa huts and endless rows of rice land.

In one such abandoned nipa hut, young townmates did some merrymaking, with some of them proudly showing off their newly “baptized” private parts in a triumphant show of their new state of manhood. One such fellow grew up to become a lieutenant and, in the early ’80s, I read in the papers that he died in an encounter with Mindoro insurgents.

That rite of passage was memorable in the summer after grade school.

First-year high school found us in this battered building near a store that rented out Liwayway and Bulaklak magazines, including local comics.

Come recess time, male classmates would check the bandage on their private parts in a secluded part of the school where they thought nobody was watching—until they heard girls giggling in another room.

Once healed, they’d go swimming naked in that river behind our school. In those days, nobody thought of swimming in birthday suits as obscene.

Hiking from the barrio to the town proper passing along the coastline, it was common to see men jumping into the sea au naturel and enjoying the seawater with no hint of malice from island passersby. The sight was as natural as treading on the rice paddies back to town.

In the late 50s, we all trooped to this neighbor who is the only one who owned a transistorized radio. This was before Uncle Ben acquired his own.

The old and the young alike listened to Tia Dely at three in the afternoon and in the evening, we listened to the late 50s edition of “Gulong ng Palad” revived later with new casts in the 70s and 80s.

Some summers were highlighted by endless nighttime dancing. The dancing hall near the sea had an improvised fence and everybody was free to join. They reminded me of scenes from popular Fellini films. One summer, two sons of my godfather showed their skills in the new dance craze called Limbo Rock.

For me, some summers were memorable when the circus came to town.

A huge tent was put up in a vacant lot near the town hall and the main attraction was a woman named Jazmine who could walk on a wire and dance on it as if she were on an ordinary dance floor. That feat had grade-school children like us imitating her skill and, soon enough, you saw ropes tied in the backyard with kids trying to cross a distance on a rope.

There was a male singing sensation in the circus and a fan from the capital town followed him. They would make out at the back, and later emerge unmindful of the kids who got to watch an extra live “circus” treat.

But circus treats come and go, and when they left, I saw the fan in tears as she was told he was not sure when he was coming back.

Then one night, one saw another kind of treat. My first feature film starring Tessie Agana as the martyr child was shown in a big house in the western part of the poblacion.

For me, it was an event. The film distributor was a man called Compuesto. Later in high school, my love for films was manifested at the only theater in the province.

The theater is long gone and I could only look at that solitary tree near the town mall where I used to catch my ride back to the hometown after watching a “double” program.

In the summer in the early 60s, I became an avid reader of publications coming in from Manila.

Same with assorted comics sold (or for rent) in a sari-sari store near our school.

There is a woman from Virac called Tia Merly who rationed Manila Bulletin, Liwayway, Weekly Graphic (now the Philippines Graphic) and Philippines Free Press in my hometown. Indeed, I actually sold some of them to as far as Macutal barrio.

This was the summer I would discover writers Kerima Polotan and Nick Joaquin.

From this Peace Corp volunteer named William Keating detailed at Catanduanes National High School, I discovered American writers from Ernest Hemmingway to William Faulkner and John Steinbeck, among others. William Shakespeare followed suit and later the French writers from Marcel Proust to Victor Hugo.

I believe it was summer when I saw my first ballet at the Catanduanes College Auditorium in the 60s. Back then, I couldn’t afford a ticket. I had to climb a tree overlooking the school auditorium and voila, I saw and heard my first ballet music and was easily enchanted. I met one of the dancers later in my life as an arts writer. Her name is Ester Rimpos who told me she danced in Virac in the 60s with the Anita Kane Ballet Company.

It was summer when people left for the Big City. I was determined to become a writer and got my first acceptance slip and an advance check payment from the Philippines Free Press, one of the magazines I used to sell in my hometown.

In the city, summer was the season you finally saw life on another plane.

Having had your fill of the idyllic life in the province and later got your share of the slice of grim city existence, you saw two contrasting worlds with different people from the opposite world.

Summer taught you to accept life for what it has to offer and what it couldn’t.

In the autumn of your life, you see summer as the age you took flight from innocence to discover things that used to be beyond your ken.

And when you did, summer acquired a certain hue that almost always describes how you feel now.

Yes, summer is finally gone in one’s life and it is the beginning of autumn.

You can say I have come of age.

ISLAND OF MY EARLY YOUTH

I have a special attachment to this old building in the island. It used to house the provincial capitol and my late mother used to hold office there as a casual employee of the Department of Social Welfare (DSW).

Hence, I am used to the sight of old clothes being given away to typhoon victims.

From those old clothes I found a costume for my stage debut at the MLQU Auditorium in a play called Ibong Adarna. I played the role of a king and my Reyna Valeriana was no less than the award-winning stage and film actress Lorli Villanueva who won the Best Supporting Actress trophy in one past edition of MMFF.

Since we had no typewriter at home, I typed my articles for the high school paper at that DSW office in the old capitol during noontime breaks.

The old capitol building now houses the Museu de Catanduanes. My memorabilia (books, awards, citations, trophies and the like) are now in this island museum.

You get an idea of the island’s genteel past in the exhibits.

There is this 1895 window panel from the ancestral house of Don Ariston Sarmiento, including his antique typewriter belonging to the same era; a 1914 baul donated by Maria Magno; old photos like the 1928 wedding of Jose Surban and Carmen Arcilla of Calolbon (now San Andres town) along with 1938 Ballesteros-Santelices nuptials.

In those photos which clearly reflected the lifestyle of the island middle class, the gentlemen were in white suits with proper hats and the ladies looked like characters from The Great Gatsby.

This must be the era when the island was virtual rainforest, when deers roamed the island and the houses of the middle-class families (notably the Sarmientos and the Alcalas) reverberated with the music of Bach and Beethoven.

Another clue to the island’s musical past is the collection of old clarinet, tuba and violin donated by the island violin-maker Fructuoso Borja and from the old Tria Band.

Also, for viewing in the museum is a 1940s espejo (mirror) owned by island fashion designer Noli Rodrigueza, an honest-to-goodness Petromax, the bronze gas lamp of the 1940s and a photo of a 1953 picnic to the once idyllic Balongbong Falls.

Another historic photo collection is a 1950s photo of former President Ramon Magsaysay flanked by Juan and Jose Alberto and the island poet, Benito Bagadiong.

A reflection of politics in the good old days was the photo of the highly revered Congressman Juan “Oban” Alberto addressing a plaza crowd of the 1950s, the late President Ferdinand Marcos at the Virac airport and former First Lady Imelda Marcos in the island White House in the 60s.

The Marcos-Alberto ties (it lasted almost three decades) were so close, it paved the way for a seaside boulevard named after the former First Lady.

It was the Publicos who started formal music lessons in the island in 1933, and virtually for a song.

Among the violin students was actor Dindo Fernando, who also hails from the island.

Designer Rodrigueza had links to the late actor who is Jose Chua in real life and fondly addressed as Pepito in barangay Salvacion in the capital town.

Rodrigueza also designed the costumes of bold star Stella Suarez when she was still performing at Clover Theater and Maggie de la Riva when she was still guesting at the Manila Grand Opera House.

Another Clover mainstay was the island kundiman queen Carmen Camacho who jumped to

national prominence after winning the Tawag ng Tanghalan.

In the past, Catanduanes was a regular concert destination and among those who were warmly received by island audiences were pianists Reynaldo Reyes (first Filipino scholar at the Paris Conservatory); Ingrid Sala Santamaria (Aliw Awards Lifetime Achievement Awardee for Music along with Cecile Licad); violinists Donnie Fernandez and Joseph Esmilla; pianists Najib Ismail and Mary Anne Espina (now with the UST faculty); Mark Carpio (head of the Philippine Madrigal Singers); Lourdes de Leon (retired from the PPO); cellist Victor Michael Coo (based in Taiwan); baritone Noel Ascona (with the UST Singers); tenor Gary del Rosario (now with Seattle Opera); Zenas Reyes Lozada, National Artist Lucrecia Kasilag and Romania’s violin superstar Alexandro Tomescu.

The latest visitor in the island was classical guitarist Aaron Aguila who had a mini-concert after the launching of my first book of poetry, Love, Life and Loss: Poems During The Pandemic.

I found a new place to contemplate in the island in my latest visits: the Binurong Point in barrio Guinsaanan in Baras, Catanduanes and Balacay Point now closed to visitors.

I thought I could stage a classical guitar concert by the sea in barrio Batag in Virac, Cataduanes.

My grandkids loved the place we have been there twice before and after the pandemic.

LIVING IN PASIG AND BEYOND

Pasig City turned 449 years old last July 2 with the city’s 20th city executive, Mayor Vico Sotto, getting a fresh second mandate in the last elections.

Pasig—which became a city only in 1993, courtesy of Rep. Rufino Javier—was a totally idyllic place when it was founded on July 2,1573, when it received its first bell as a new mission parish named after Our Lady of the Visitation. The population then was only a little over 2,000. (As of the 2015 census, Pasig has a population of 755,300, with some 440,856 voters.) Many years later, the town turned to Our Lady of Immaculate Concepcion as its patron saint.

According to a local history book, Pasig was originally a small kingdom around the river called Bitukang Manok under Dayang Kalangitan, wife of Gat Lontok, whose illustrious son included the original Raha Soliman I of Manila.

Mass murder of the Spaniards was what Gat Andres Bonifacio literally ordered from a revolutionary house in Pasig in 1896, when he founded the Sangguniang Bayang Nagbangon as a prelude to the revolution against Spain.

It was in today’s Pasig town church across Plaza Rizal and Pasig Museum that the American Commission, headed by William Howard Taft, met on June 11, 1901, creating the new province of Rizal and making Pasig its capital.

Across what used to be the town glorietta was the mansion of the first pharmacist of Pasig (and later town mayor), Don Fortunato Concepcion, whose daughter Vina became the wife of actor Luis Gonzales.

His house, built in 1937, was where President Quezon used to make political visits. It was the same mansion where Pavarotti’s first teacher from Modena, Italy, Arrigo Pola, used to stay before fulfilling his engagement in the town glorietta.

In the late ’40s into the early ’50s, the pride of Pasig and the entire country was Pasig-born tenor Octavio Cruz, who sang Verdi and Donizetti operas at the Manila Metropolitan Theater, the Manila Grand Opera House, and the equally historic Far Eastern University (FEU) Auditorium.

The first and last Filipino prizewinner of the 1956 and 1961 Paganini International Violin Competition in Italy was a lady violinist from Pasig, Carmencita Lozada.

One of the National Artists (Music) is also from Pasig—Ramon Santos, who used to direct operettas in the ’60s in a local school.

I became a Pasig resident in 1982, when a violinist of the Philippine Philharmonic asked me to move from my Parañaque house and live in a Rosario apartment. At the time, we were both employees of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP).

I used to watch Lozada perform at CCP without knowing she was from Pasig, and I met Santos also at CCP, where he was then one of the movers behind the National Music Competition for Young Artists.

I live and breathe Pasig history where I live now. A few houses away from my home in Marcelo H. del Pilar St. is the house of Valentin Cruz, who worked closely with Andres Bonifacio on the plot to oust the Spanish colonizers.

Just across the street used to be the former Pasig glorietta (now Jollibee), where Arrigo Pola used to sing. His holding area is now the Pasig Museum (the former Fortunato Concepcion mansion).

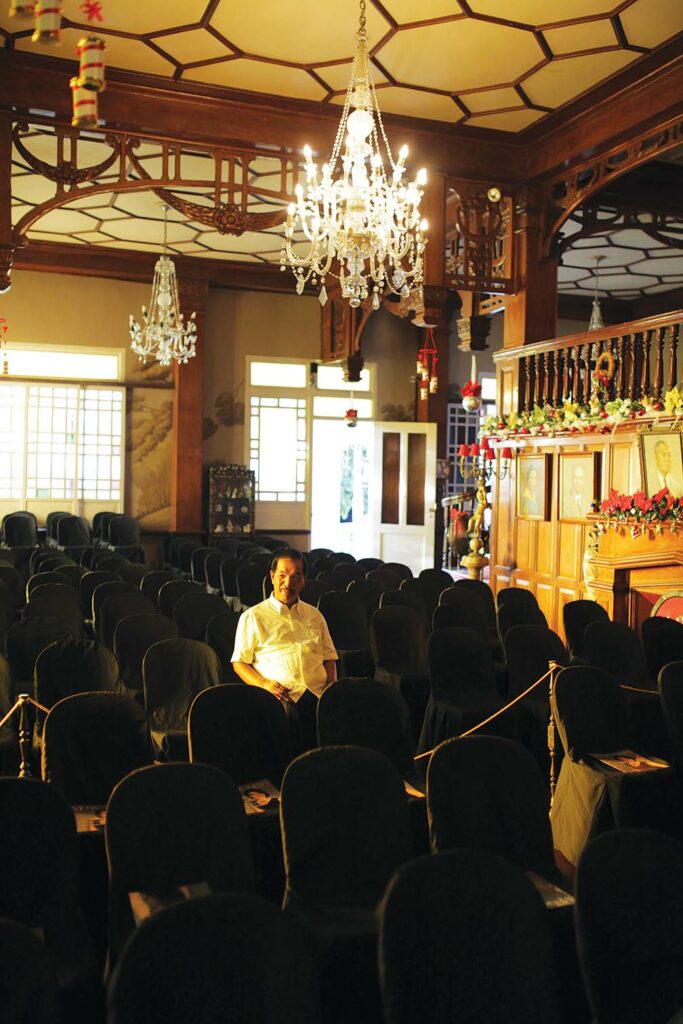

When I learned that Quezon frequented the Pasig Museum in the late ’30s, I decided to convert the living room into a recital hall and founded the annual Pasig Summer Music Festival in 2002, which lasted five years.

One of my special guests in the Pasig Museum concert series was Maestra Mercedes Matias Santiago, the first Filipino soprano to sing Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. She gave voice lessons to former First Lady Aurora Quezon.

When Santiago sang the role of Amina in Bellini’s La Sonnambula at the Manila Grand Opera House in the mid-1930s, President Manuel Quezon was in the audience, but a blackout hit the opera in the sleepwalking scene. There was a long intermission. The opera resumed at 3 am, when power was restored.

After that dramatic performance of the Donizetti opera, Quezon sent Maestra Santiago a seven-foot bouquet with the inscription “Ruiseñor de Filipinas (Nightingale of the Philippines).”

It was also Quezon who recommended that Maestra Santiago be given a teaching job at the University of the Philippines (UP) College of Music, which was founded in 1916. The Maestra’s student assistant was no other than the young Lucrecia Kasilag, who would become CCP president, then National Artist for Music.

Among the performers in my Pasig Museum concert series were pianists Cecile Licad, Mary Anne Espina, Najib Ismail, tenors Otoniel Gonzaga, Nolyn Cabahug and Lemuel de la Cruz, and violinists Diomedes Saraza Jr. and Chino Gutierrez, among others.

One of my last Pasig Museum concerts was frequented by National Artist for Literature and former Philippines Graphic editor-in-chief Nick Joaquin who had an ice box of cold beer beside him.

Two future national artists frequented my concerts: the late, recently declared National Artist for Film Marilou Diaz Abaya and National Artist for Music Fides Cuyugan Asencio.

For reviving live classical in the city, I was named one of the Outstanding Pasigueños in the field of music in 2002. It was the same award that went to violinist Carmencita Lozada and now national Artist for Music, Ramon Santos.

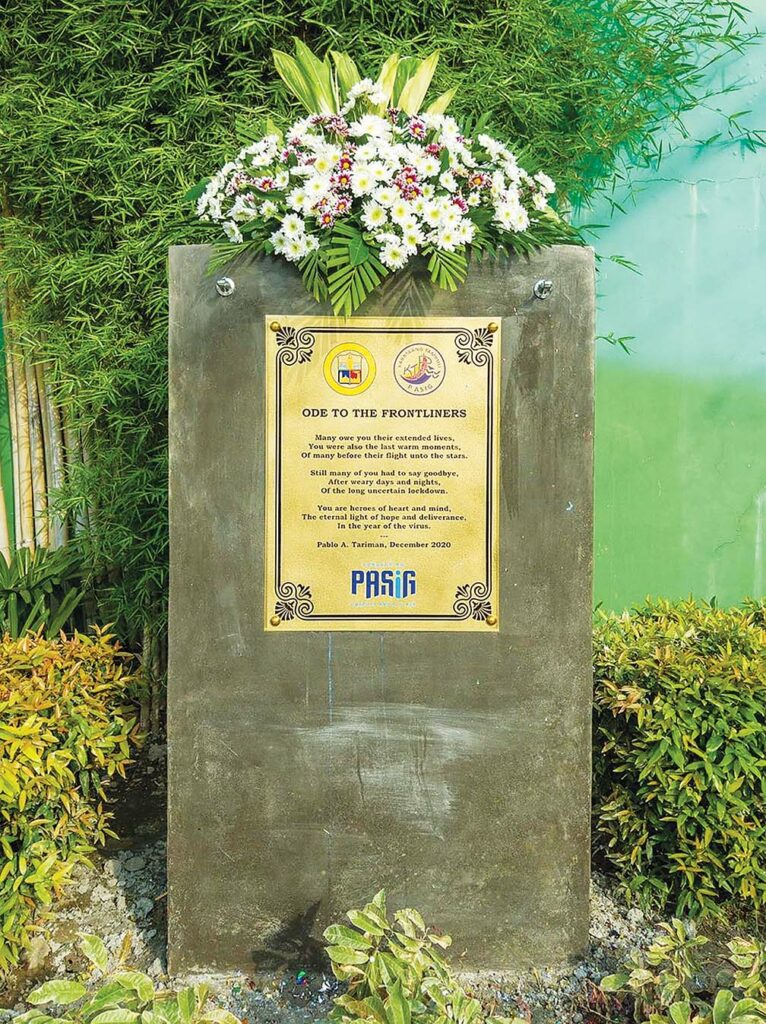

In 2020, a cultural staff of the mayor asked me to write a poem dedicated to the frontliners of Pasig City.

On Dec. 30, 2020, in public rites, the poem, Ode to Frontliners, was made into a marker installed at La Familia Plaza (formerly Plaza Bonifacio). Present at the installation of the marker were Mayor Vico Sotto and Pasig Rep. Roman Romulo.

(Meanwhile, Mayor Vico also made history when he won in 2019 and ended the 27-year-old Eusebio political dynasty.)

Speaking of heritage house in Metro Manila, maybe I should include Mira-Nila in Quezon City.

In the early ’90s, Sen. Helena Benitez hosted a welcome dinner for mezzo soprano Liang Ning (the first Chinese opera singer to make a debut at La Scala di Milan). It was held at the Benitez clan’s Mira-Nila ancestral house in Quezon City. Built by Conrado Benitez and his wife Francisca in 1929, Mira-Nila hosted the first reception for the first Commonwealth officials led by Quezon, who donated two chairs with the presidential seal in the main hall.

Among the guests were Kasilag, music critic Tony Hila, tenor Gary del Rosario, and yours truly.

REDISCOVERING ILOILO’S HERITAGE HOUSES

Sometime in 2017, two Lopez heritage houses in Jaro, Iloilo City, fascinated me: the Boat House mansion of Don Eugenio Lopez Sr., and the Lopez Heritage House (aka Nelly’s Garden) of Don Vicente Lopez.

Of the two mansions, I have a special preference for Nelly’s Garden, which looks like the

mansion in the classic film, Gone with the Wind.

After checking the state of the piano and the seating capacity, I decided that Nelly’s Garden would be my next recital venue for an all-Chopin recital by Licad.

It happened on Nov. 29, 2018. The crowd gave the pianist three standing ovations. It turned out that my new concert venue had served as elegant setting for receptions and meetings with governor-generals of the Philippines including Frank Murphy and Teddy Roosevelt Jr.

On top of that, two famous women used one guest room of Nelly’s Garden: former First Lady Imelda Marcos and former President Cory Aquino.

Still on Quezon connections, it turned out that Iloilo City was officially established in August 1937 with the signing of the charter by Quezon after the National Assembly had created the four cities of Iloilo, Cebu, Zamboanga and Davao.

Present at the ceremony were Assemblymen Pedro Gil, Tomas Confesor, Victorino Salcedo, Ruperto Montinola, Jose Zulueta, Speaker Gil Montilla, Secretary Elpidio Quirino, Jose Aldeguer, and journalists from Iloilo.

I covered the 80th Iloilo City Charter Day presentation that featured the Manila Symphony Orchestra performing at the historic Molo Church and Iloilo City Convention Center.

After an evening of Bach and Beatles songs, over a thousand Ilonggos led by Sen. Franklin Drilon gave the orchestra a rousing standing ovation. It marked the first time a symphony orchestra was heard in Molo Church. “Music has charm and it contributes to the refinement of the soul,” said Drilon in his welcome remarks.

I also learned that Quezon was baptismal godfather of Presy Lopez-Psinakis, daughter of Don Eugenio “Eñing” Hofileña Lopez Sr. and Pacita “Nitang” Moreno Lopez.

As related in the book, The Saga of the Lopez Family, the baptism coincided with the inauguration of The Boat House, Don Eñing’s modernist mansion in Iloilo City, designed by architect Fernando H. Ocampo. Quezon stood as godfather while the beautiful Aurora Reyes Recto, Claro M. Recto’s second wife, was godmother.

Two years later, Don Fernando Lopez invited Quezon as special guest at the baptism of Lopez’s daughter Milagros. On the day of the baptism, Quezon disembarked at the Iloilo City waterfront met by thousands of cheering welcomers. He drove straight to the Jaro Cathedral with an entourage of 30 cars. Later, he attended a dinner dance at Don Fernando’s mansion.

Nelly’s Garden owned by businessman and philanthropist Don Vicente Lopez and Elena Hofilena in Jaro district in Iloilo City has a colorful life linked with music and the city’s illustrious past.

The heritage house was built in 1928 on the same decade the Manila Symphony Orchestra was born in 1926. The mansion was only a year old when violinist Gilopez Kabayao was born in Fabrica, Negros Occidental in 1929.

Named after the eldest daughter Nelly, the heritage house became a historic venue for reunion of Iloilo’s music and arts lovers when world-acclaimed Cecile Licad opened a concert series on November 29, 2018 with an all-Chopin recital that earned three standing ovations.

It must be noted that the port of Iloilo was opened to world trade in 1855, six years after Frederic Chopin died in Paris.

By coincidence, Licad and the Ilonggo pianist Nena del Rosario Villanueva—both aged 11 then—went to the same school, the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, where they were honed by great pianists of their time.

Villanueva studied under Isabelle Vengerova and briefly with the piano icon Vladimir Horowitz. Licad found a legendary pianist and teacher in Rudolf Serkin.

The celebrated star pupils of Curtis, Villanueva and Licad won piano competitions in New York in their teens (the former in the mid-50s and the latter in the early 70s).

By coincidence, the last concert series at Nelly’s Garden in 2019 was a tribute to Ilonggo tenor Otoniel Gonzaga.

The coming concert of internationally acclaimed Filipino tenor Arthur Espiritu at the University of the Philippines Visayas on October 20 is also in memory of Gonzaga, on his fourth death anniversary.

Like Licad and Villanueva, Gonzaga received his training at the Curtis Institute of Music under the tutelage of English tenor Richard Lewis and American soprano Margaret Harshaw and later from Prof. John Lester.

While in Curtis, Gonzaga won first prize in the Marian Anderson International Singing Competition in Philadelphia. Serkin heard Gonzaga in a rehearsal of Cosi fan tutte and commented, “Most singers sing loudly but I like the way Gonzaga sing because he sings musically.”

Serkin’s admiration for Gonzaga later translated into an endorsement for him to be the one of the soloists in Beethoven’s Choral Fantasy with Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra.

By another stroke of coincidence, Gonzaga has sung the lead tenor role in La Boheme in

Frankfurt Opera in the early 80s with the Mimi of the Romanian diva, Nelly Miricioiu, who gave tenor Nomher Nival a specialized one-month masterclass in London.

Nival was the last featured tenor at Nelly’s Garden in 2019. Along with soprano Jasmin Salvo, clarinetist Andrew Constantino and pianist Gabriel Paguirigan, they were given a standing ovation by an Ilonggo audience led by Mayor Jerry Trenas.

FOREVER 60

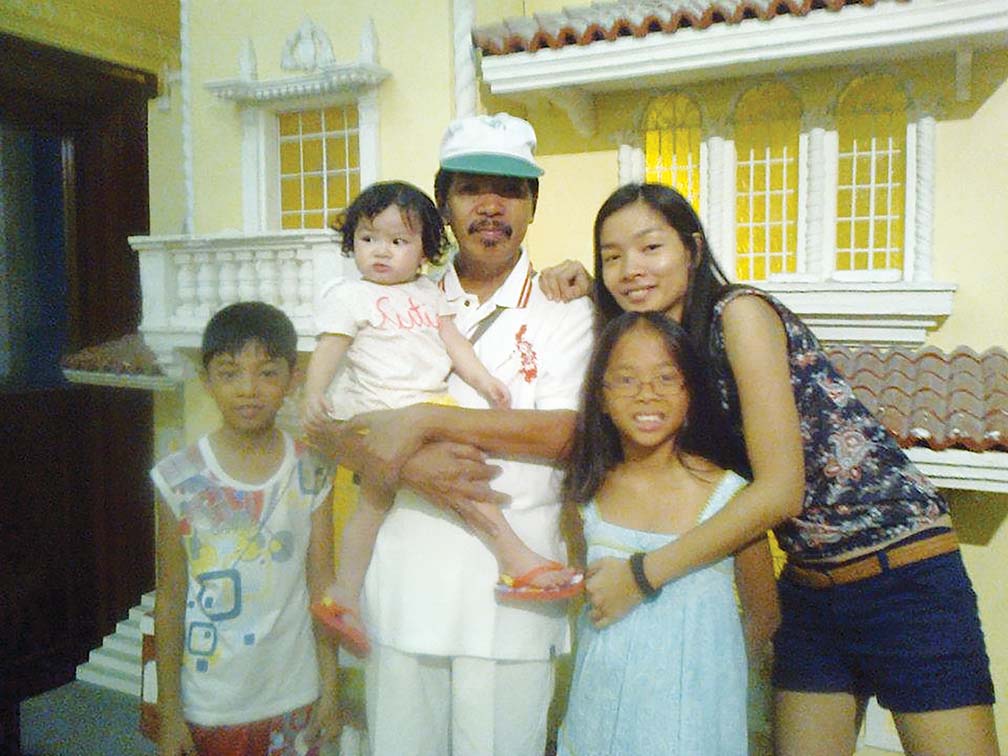

In December last year, my sixth grandchild came into this world after my first grandson, Emmanuel, was born 19 years ago.

On another front, I am a musical father of countless concerts that started at CCP, Philamlife and innumerable other venues from Tuguegarao to Davao, Catanduanes to Palawan, from concert halls to restaurants and heritage houses like Nelly’s Garden in Iloilo City.

I became a senior citizen 13 years ago, but to this day, I have not attended a single senior citizen gathering in San Nicolas, Pasig. But I have learned to be comfortable in the LRT-MRT train coach for senior citizens, the pregnant and the handicapped.

But I do use my senior citizen card—while making sure no one is looking behind my back. Same with my white booklet when doing grocery shopping that doesn’t exceed P1,000.

I nearly growled at a Mercury Drug saleslady when I was told I could not use my blue card to buy vitamins for my grandchildren.

I admire actor Pen Medina for being open about his age and senior citizen card.

Beside Vergel Santos (the editor and book author) and Randy David (the writer and educator), I look like a fake senior citizen with my dyed hair and mustache.

Twelve months into quarantine, I suddenly had white hair. My granddaughters shrieked when they saw how I looked now, “What happened to your hair Papu?”

I took it all in stride as I realized that’s the look, I should have at 73.

For years, I projected being forever 60. It felt better looking that age when attending showbiz presscons with millennials.

Back then, I used to bike and swim till kingdom come.

At the moment, they are luxuries I can no longer afford.

I used to drink till kingdom come, but I know I am no longer the drinker who had nothing to fear from Joseph Estrada and the late Fernando Poe Jr.

In the company of John Lloyd Cruz and Ping Medina in the birthday party of Ronnie Lazaro, I shifted from San Mig Light to tequila.

I let everything out, tequila and all, on Ortigas Avenue on my way to Pasig at three in the morning.

It’s a pity that one of my favorite actors, the late Eddie Garcia—who made it a point to offer me beer during movie presscons (to the chagrin and horror of star-builder Ethel Ramos)—didn’t drink.

While I have not come to terms with the physical look of a senior citizen, I have more or less come to terms with everything about my life.

What was my life like when I was the age of my grandchildren?

Like I said in the beginning, I was born in a village by the sea called Tilod in Baras, Catanduanes.

I saw my first eclipse in Tinambac, Camarines Sur, at age 6, while looking for clams on the seashore.

My first family portrait with cousins (now all in the US) was taken in Guimba, Nueva Ecija, where an aunt and uncle made their fortune as rice dealers.

The early ’60s saw me playing Jose Rizal in an elementary graduation play in Baras, Catanduanes.

I appeared in a play called Seven Years (by Fidel Sicam) mounted on the auditorium of Catanduanes College, where three eminent lawyers from the island came from: Jorge V. Sarmiento (now with Pagcor), Rene Sarmiento (now with Comelec) and Cesar Sarmiento (now a congressman).

This was the decade I saw my first ballet on the island. Since I could not afford a ticket, I climbed a tree adjacent an open window overlooking the stage of Catanduanes College and saw the best of Anita Kane Ballet in the mid-’60s. I landed on the same stage in the play “Seven Years.”

In high school, I won some extemporaneous speaking contests and lost a regional one to Linda Bolido (representing Masbate, and now retired from PDI).

The late ’60s saw me winning my first essay writing contest in Metro Manila sponsored by the BIR, and in the jury was one of my favorite writers, Carmen Guerrero Nakpil.

In the ’70s, I got my first job (Graphic magazine) and lost it to Martial Law. I ended up with Kit Tatad in Malacañang in the company of the late Larry Cruz (the restaurant specialist) and Zenaida Seva (the astrologer). This was the decade I married and became a father, found other government jobs and promptly lost them.

This was the decade I met the then 14-year-old Cecile Licad in Legazpi City, and that encounter led me to the CCP in the late ’70s.

In the ’80s and ’90s, I met the world’s greatest artists: Russia’s Maya Plisetskaya, Cuba’s Alicia Alonso, Italy’s Luciano Pavarotti, Spain’s Montserrat Caballe and José Carreras, Mexico’s Placido Domingo, Romania’s Nelly Miricioiu and Alexandro Tomescu.

I’ve come to realize that writers do not make good businessmen and that good concerts do not necessarily translate to good income.

You relish the standing ovations but bravely face the deficits.

There are no national awards to gloat over (although I got a few from Cebu, Isabela, Cagayan, Legazpi and Catanduanes, mostly for bringing classical music to the countryside), no earthshaking accomplishments to brag about during alumni homecomings.

But in December 2018, I became the first performing arts writer to receive the Aliw Awards for four decades of reporting the arts.

It felt good to get my first rock star treatment with my co-awardees—Lea Salonga and actor Raymond Francisco—in the audience.

In February 2020 after the Taal volcano eruption, earthquakes in Mindanao and the initial phase of the corona virus invasion, I received the Leaf Award for more or less the same reasons: devotions to the arts by covering them come floods and typhoon signals.

But then, there is no house to speak of, not even a battered car (I still take jeeps, buses and tricycles). I used to keep in good shape a worn-down bicycle but now I leave the biking to my grandson who has become my technical consultant for anything I don’t understand in GCash, FB and internet connections.

On this third year of the pandemic, friends and acquaintances have come and gone with some of your favorite artists meeting the same fate.

I am a father of three and lost one in 2021. This was the year I watched second daughter

engulfed by flames in a Bacolod crematorium.

I am a grandfather of six and nothing else on the side. I have earned some virtues and probably lost some of them. You come face to face with your impossible side, but you continue to surprise yourself by being capable of basic goodness and generosity.

At this age, you can say, “Been there, done that.”

After not becoming the person you want to be, you say, “There is no use crying over ‘spilt virtues,” as someone in my Wednesday “Virtuous” Group would say.

Indeed, this is the phase when the many sides of life stare at you in the face and, without hesitation, you try to live and reconcile with the best and the worst that you have become.

When I met with my Frankfurt-based daughter and granddaughters in Singapore three years ago in July, I knew it was going to be one of the last times we would be together.

Over lunch on the 56th floor of Marina Bay Sands in Singapore, I reflected on what has become of me.

But in the middle of my lockdown agony, I turned to poetry and had a long-overdue reunion with my soul.

Before the year was over, my poem turned into a marker with my tribute to frontliners.

In the middle of another upsurge of the virus, I got an invitation—not as an impresario—but as a man of poetry. I was asked to talk about my life with poetry during the pandemic.

Last year, I became one of 160 poets in the Asian region included in the anthology, The Best Asian Poetry 2021-22, edited by distinguished Indian poet Sudeep Sen. The other Filipino in that anthology was novelist Danton Remoto.

As I look back now, there isn’t much to gloat about.

Turning 74 on Dec. 30 in what I hope would be the end of the pandemic, I have only one achievement, if you can call it such: I have come to terms with life—pandemic, bad governance, lost jobs and all.

The essence of my personal journey I found in Tennessee Williams who once said in an

interview: “It is the pursuit of beauty in things and people that is the journey—the real journey. I was happiest when I sought beauty in words and music and images. I was happiest in movies or in the middle of a symphony—whatever allowed the mind to ponder all that was possible and glorious. The world, I suppose, is the result of actions taken by people possessed of an image or an idea, and the world I care most about is constructed from those images that remind someone of the beauty and the nobility of people… I want to find and host the beauty of the world.”

True, I do not own a substantial piece of theater or cinema or music or literature. I was just

happy to watch and absorb them.”

On my own, I try to live the arts the best way I can.

Through poetry.

Through constant reporting of the arts whatever I can manage.

And keeping classical music alive in the city and the countryside.