Blood has a peculiar, coppery taste in the mouth. Carmen smells it first, a familiar metallic tang from rusted iron reminiscent of white sartin cups in her youth. Hers had a special red lining, instead of the usual blue ones, a gift from her mother. She faithfully used it daily, until eventually the white enamel chipped off, and water bit into the exposed metal, marring its pristine whiteness.

A loud yet faraway roar fills her ears, like when she willfully stood under the onslaught of a waterfall when the rain has doubled its current. She covers her ears to block the noise, but her hand slides off something sticky, like molasses. Despite her tunneling vision, Carmen sees the crimson stain and is surprised at her absence of alarm. With a clinical calm, she traces the trail of blood. It starts from a mass of matted hair, drains as a single rivulet, makes a detour for her lips to smear her teeth and eventually drip from her chin. She tries to stand up, trips on a pleat of her skirt and stumbles forward.

Barangay Igang was named in deference to a single outcropping of white limestone easily recognizable a short distance from the dirt road. During Sundays, the locale swells to become the “tabu,” a makeshift wet market and dry goods center where in a weekly occurrence, precious commodities like fish and squid swam their way up to the mountains in rusty tricycles, judiciously entombed in large chunks of ice and frigid water. Off to the side of the road, one face of the rocky hill was half the circle of a wooden arena, where gamecocks ruthlessly slashed at each other with glinting, sharpened blades. The air rang with cries from delighted drunkards and enraged gamblers, having wasted a week’s pay on such frivolities. On other days, the site was abandoned, with a few upturned chairs and bamboo tables as evidence of promised Sunday festivities.

It was night; the last tricycle carried the visiting rural nurse back to the town center two hours away. Kap Berto, in a predictable frugal turn of mind, turned off the lone streetlamp that marked the ingress to their community. It stretched three bamboo poles from his house and was inextricable from his own electricity bill.

Carmen shrugged, the dimming of the single bulb did nothing to dampen the moonlight that bathed the area in an effusive, otherworldly luminosity. To her right, the igang glowed in response to the moon’s ministrations. It curiously resembled the massive skull of a fallen giant, the numerous holes looked like several eyes in various states of wakefulness. In one of the sockets was the flickering tongue of a dying candle. Carmen had started the weekly post-tabu ritual shortly after her mother’s death, culminating in a monologue of Latin prayers to her parent. A decade hence, she began including her father’s name in the conversation.

With an audible stuttering, the wick succumbed to the molten wax. Carmen ended her prayer, and reverently placed her forehead on the rock’s surface. She gathered her skirt about her and trekked the reddish-brown path which would lead her home. She smiled faintly at Kap Berto’s seven-year-old son who peered at her through their window, his head silhouetted against the television’s light. He did not wave back.

There are two constants in Carmen’s solitary life: dust and sugarcane. Despite the alabaster namesake, the barangay straddled a large vein of ferrous rich soil. It erupted from beneath the limestone outcropping, and like a crimson ribbon, meandered its way through the entire village, cut across the sugarcane fields, and made a lazy detour for Carmen’s nipa hut. The path was distinct as if lines were drawn using a pen, and no vegetation grew in its midst. During the monsoon, the rainwater deepened the color, transforming it to a river that ran red. Even the air was heavy with the metallic aftertaste. Dust would come back with a vengeance when the water had evaporated. It permeated everything; grappled intimately with the skin under the nails, stained the fibers of clothing and floated innocuously in the air eddies to embed itself in the mucosal lining of the lungs. It was ubiquitous. Carmen welcomed it, though, marking the seasons with the severity of its abundance.

At 55 years old, Carmen had intimate knowledge on anything sugarcane. She could extoll the various virtues of different varieties: from the tall, lanky, dark-skinned ones with the intensely chewy meat which could impale a sliver down your throat, to the fat, green crumbly ones which seemed to be like soft cotton steeped in sugared water. She could tell, with her nose in the air and a raised finger wetted with saliva, when the best time to plant cuttings and to fertilize them would be. Early in the morning, she would speak respectfully to the ground, crumbling hard blocks of reddish clay in the palm of her hand. Her parcel of land dutifully produced bundles of sugarcane, filling the 6×6 truck she rented, which grumbled and wheezed as it laboriously carried her produce to the squat, century- old sugar mill people still referred to as Central.

Carmen is a thoroughly tanned, strong, handsome woman despite her age, with sleek wavy hair interspersed with strands of silver, heavily weighed down by coconut oil. What made her remarkable are her eyes: pale brown orbs with flecks of gold and green and an intense, unflinching gaze. They were unusually large for her face, made more pronounced by a thin aquiline nose and barely discernible lips. “Morugmon,” people would mutter, referring to the large nocturnal birds that hunt by night on soft, whispery wings. The truth she suspected was less avian in nature; several pointed questions on her father’s lineage ended vaguely with the arrival of a new parish priest of Spanish descent, and a population of decidedly light-skinned children cropped up among the devout women of faith.

Carmen was the unofficial barangay herb woman and assisted childbirths whenever the local government-employed midwife was in the throes of tuba-induced inebriation. The community held Carmen in high regard but was unnerved by her unearthly calm and indifference. People gave her a wide berth during her walks, a palpable silence hushing the crowd. Nobody disturbed her during her post tabu ritual at the igang, while she intently listened to absent voices, her eyes glazed and unfocused. She never married, detesting the idea of a marriage with children and a spouse tying her down. Solitary life does not usually mean a lonely one.

She continued walking on the narrow dirt road, her ankle-length skirt made a soft, swishing sound as it rubbed against her legs. Her house was still a kilometer from the outskirts of the barangay. Towering green sentinels of sugarcane rose to greet her as the foot walk became even tighter, reducing to accommodate just one step ahead of the other. She stretched her arms out on both sides, the leaves’ jagged little teeth openly grazing the inside of her arms.

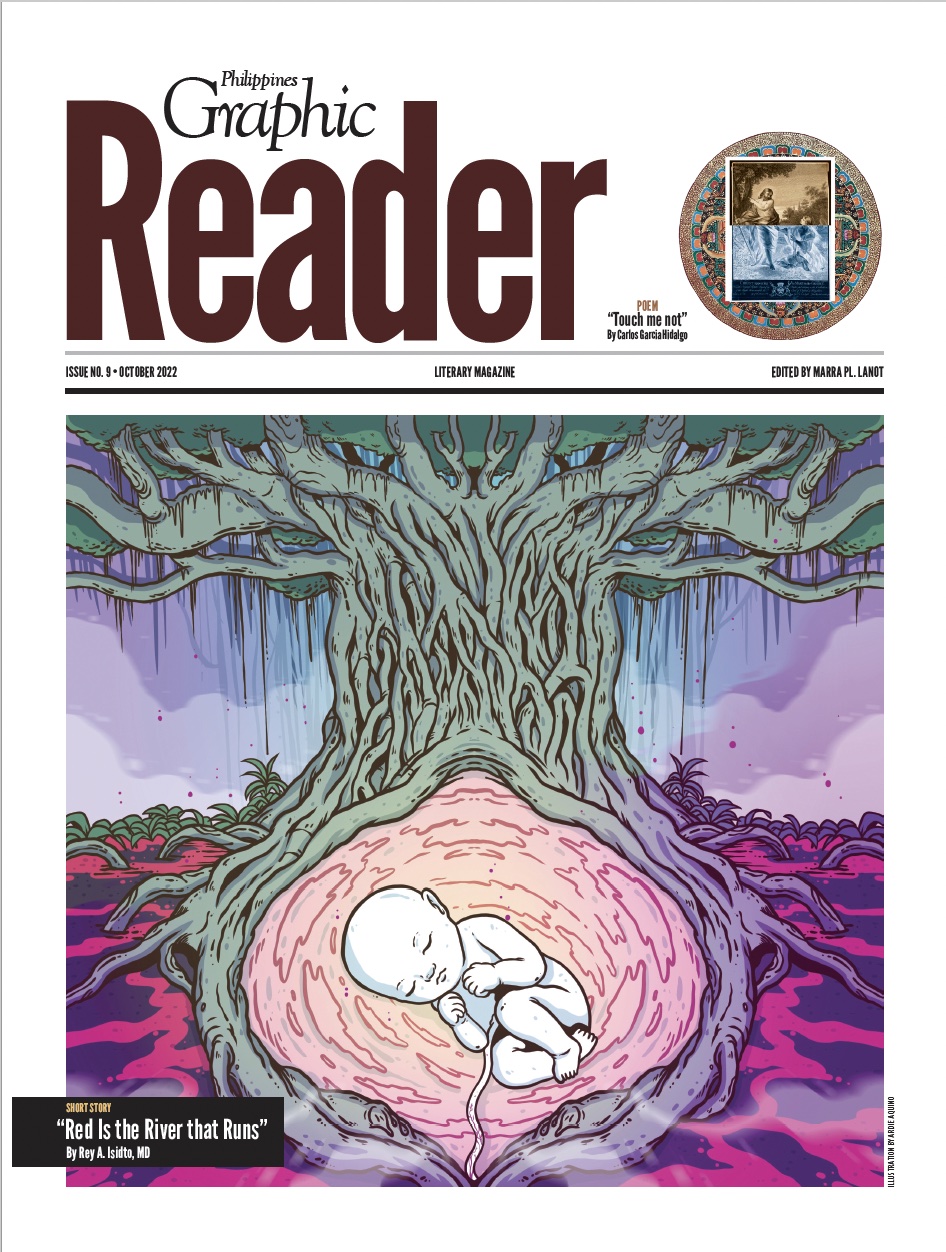

Hacienda isa kag tunga—Hacienda one and a half—Carmen whimsically called the land she owned. The entirety of her property, passed down from her father was one-and-a-half hectares. Well, less than that, as the area that perched on top of a slight elevation was home to a platoon of narra, several avocado trees and a grove of peculiar coconuts that bore fruits with a creamy, semi-solid center. An undisturbed brook of indeterminate origin meandered its way parallel and crossed through the land to drop like a miniature waterfall to the waist-deep canals that flanked the road. Towering above them all was a single acacia tree, tall and imposing despite its centuries-long existence. Its massive trunk supported branches as thick as a man’s thigh. The lower canopies favored sprouts of staghorn ferns, their verdant antlers swaying with the slightest breeze-sigh.

Carmen climbed the tree once in her youth, struggling past the ferns to finally secure a spot among the upper emergent layer. She could see vast open spaces of prolific greenery, the dirty muddy river to the right, and the sugar mill to the far north, spouting white plumes from gargantuan smokestacks. The earth was taking a drag from the cement cigarettes and breathed it out in interminable puffs, the heavy sweet-sour odor of cooked molasses settled like a miasma. Strong, whistling winds diluted the scent, like the diaphanous perfume of a forgotten lover.

Despite the dizzying height, Carmen was underwhelmed, thoroughly unimpressed. She decided on this, days later, as she was picking the scabs off healing welts that is the natural denouement when tender, youngling flesh meets the supple wood of a freshly cut guava branch, enthusiastically wielded by her fully enraged mother, lashing at her with such vociferous enthusiasm when her arboreal ascent was discovered.

“Nanay,” Carmen reflexively murmured to herself. Her mother was the real medicine woman, Carmen, a pale shade. Nanay Dina embraced with her whole body, and Carmen, though thoroughly engulfed never felt suffocated. She had an oily, sweet aroma that spoke of ground-up herbs and seeds and an earthiness that came from copra. Nay Dina was infinitely patient when she taught Carmen the herbs and flowers that needed to be gathered at a particular time in a specific way for the tinctures that healed cuts and bruises efficiently. She even had an entire armory to ward off the evil spirits and engkanto which populated the mysterious forest that ringed the base of the mountain nearby. She was a devoted Catholic, hence the cross, but she melded a hodge-podge that agreed well with her conscience. Nay Dina belonged to a long succession of manog luy-a, those that cured with the perceived help of the natural and the paranormal.

Someone was at her gate, frantically pacing the length of rosal bushes that hedged her property. A lone figure of a man brandishing a quavering flashlight looked up from his muttering.

“Is it time?” Carmen asked, unperturbed.

She was half a foot shorter than her tall, gangly visitor but she was able to calmly look down on him, resting a cool hand on his shaking shoulders. Ben dumbly nodded, eyes pleading, while a free hand mashed his face in an unconscious attempt to hasten her steps. He was always the nervous one, with facial and body tics that bordered on the ridiculous. She remembered delivering him one lazy Sunday afternoon to a mother that looked like a fat, legless termite larva bored and lounging on the banig, quivering with hunger pangs rather than childbirth pains. She eventually pushed out a long-limbed infant with a modicum of effort, grunting in satisfaction.

Ben was one of the first babies in a career. Tonight, it has come full circle. Christine, his wife, was ready to give birth to their firstborn after several years of drought and a record four miscarriages. Christine was a delightfully shy, yet affectionate child and she grew into a graceful woman who always had a kind word for anybody and everybody.

A cursory glance at her medicine cabinet supplied Carmen with what she needed. She deftly took out amber-colored bottles with various roots and barks steeped in different aromatic oils to help steady the parturient, a cloth for a poultice that hastened contractions which she prepared days earlier and an evil-smelling ball of mud drenched in camphor oil that was guaranteed to wake up even the dead. Lastly, she clutched the miniature bamboo cross that belonged to her mother.

Carmen strained at the bit when she was first introduced to her mother’s healing, petulant at the unwanted responsibility. She was forced to attend every session, and to her chagrin, even childbirth. Carmen hated childbirth. Bile rose to her throat as she witnessed the eventual laceration of the vagina, the opaque liquid that gushed out, and all that blood! Even the life-giving afterbirth looked like an alien device designed to peel your face off. The babies were no consolation. They were toothless, screaming gremlins with their squashed up faces and the way they flailed their hands and feet about, gasping for air.

Ben and Carmen rapidly closed the considerable distance between them and his house, which was strategically situated near the main road, a stone’s throw away from the remarkable igang. They sped through the sugarcane with nary a word, accompanied by the rustling and audible whispering of giant leaves. A few meters away, the house and sari-sari store the couple owned were visible.

Christine was already in the paroxysms of labor when they arrived, writhing in a panicked state of pain and discomfort. Ben was quickly dispatched to boil water to sterilize towels and lampin. Not that she needed any. It behooved Carmen to be prepared for the possibility of precipitant labor, which could be the case here. Not due for two weeks, the clarity of timing was suspect. Entertainment in a place as far flung as theirs consists of frequent switching between two warring TV stations, and ever since one was silenced by the national government, the lack of variety resulted to doldrums in the evening.

Pregnancy cravings can be a subconscious effort in the woman to punish her partner for the early days of bloating, nausea and vomiting and the vast swings of emotions. Christine during her fits of first trimester agony, begged for macapuno, not the candied variety which was heavy with sugar. No, she yearned for the raw goo that dripped from the crushed skull of a coconut fresh from the tree. Ben buckled under Christine’s blistering tirades and her incessant groaning for food but not one specimen in the barangay yielded the mutation.

One morning, Carmen found the couple at her gate. She rarely let anyone in, content with visiting the sick and gravid in their homes. Her home and the surrounding property were holy ground. She treasured her privacy.

“Please, Tita. Is that macapuno? Can we have some, please?” Ben was a blubbering mess of kowtowing and pleading while Christine stood nearby, grimacing through the hunger pangs. Carmen leveled an unflinching gaze at them.

After a pregnant pause, the gate opened with a soft swish, and Christine made a beeline for the batalan that received part of the brook’s water to wash off the grime and dust. Ben hurriedly shed his sandals and scurried up the coconut tree. A thud later and he was hurriedly ripping the husk off a chosen coconut, and with few taps of the bolo, it conceded its prize: thick clots of white cream. Christine squealed with delight and started shoveling the macapuno into her mouth by the spoonful. Carmen and Ben looked on in unconcealed horror and astonishment.

The next day, they were back, competing with the sun, the dew still heavy on the leaves, the air heavy with perfumery coming from the rosal hedge. Carmen reluctantly let them in.

The daily pilgrimage continued for months. Carmen’s stoic solitude was gradually ground out by companionable laughter as all three fell into a relaxed rhythm; she tended the crackling fire for the requisite coffee and chocolate, Christine set the narrow outdoor table for the small breakfast they usually brought with them, and Ben took his time with the coconut trees, finding out which one was ripe enough to produce the gel-like consistency his wife specified. Carmen can scarcely remember the days when she started the morning by herself, the memory a dim and distant feeble roar in the seashell of her mind. At dawn, she stoked the embers for the coffee and waited expectantly for her visitors.

The young couple stayed for two hours at the most, exchanging food and companionship for macapuno, until the trees were nearly bereft of fruit. Fortunately, the intense cravings mellowed to random pregnant harkening.

The coconuts had long since been left untouched, yet the pair turned up like clockwork every morning, eager to start the day. Christine always feigned the need for exercise, an excuse she flimsily made since the trek comprised mostly of rough terrain. The path was eventually dotted by several chairs, which she used to take a momentary rest.

Carmen stood at the gate and waved goodbye. Christine’s pregnancy was already noticeable through her loose saya and evident by her carefully calculated steps. She realized they spent the day barely talking to each other. The comfortable silence spoke volumes. Yesterday, Christine, who was orphaned at ten years old, had reflexively called her Mama. Carmen froze, her heart seized up by a warmth unlike anything she felt. There was a rushing of phantom wings, and her heart was buoyed by the abrupt lightness of immeasurable emotion.

“Mama,” Carmen repeated to herself, the alien word rolling about her tongue. She felt a sudden shuddering shift in her own personal cosmos, and something inside clicked in place. A family was what she never wanted but apparently needed. A daughter, a son and an apo. She beamed, a huge smile bisecting her face.

“Ma, something is wrong with the baby. It’s not time yet,” Christine insisted, clutching and grappling at Carmen with imploring hands, seeking answers for questions she could not form. Christine was delirious, sweat gathered and dripped from her in tiny streams of pain. Her huge abdomen convulsed in a rhythmic pulse of suffering, and she buckled with every agonizing ripple, her diminutive frame threatening to break with each spasm.

Carmen silently agreed with her. The cervix was starting to open, yet she could not grasp the firm head and tiny wisps of hair. An unnerving vacuum greeted her searching fingers.

The night bled into the morning, and the midwife arrived, bowing apologetically, just recently awakened from her alcohol-ridden stupor. Four hours in labor and there was no progress from all the suffering. Ben had already contacted the town ambulance. Carmen rarely left Christine’s side during the entire ordeal, applying fragrant oils while gently massaging her gravid abdomen.

At one point, Christine choked in mid-breath, opened her unfocused eyes, and emitted a blood-curdling cry. The baby slid out with a rush of murky birth waters, deathly still, limp and unmoving. It was perfect in a way that most infants are born, except that its unnaturally large brown eyes were lidless, perpetually open. The paucity of flesh extended upwards. There was no skull, no brain, just knobs and lumps of flesh. The hollow it formed managed to scoop into its cavity the vernix caseosa, the white cheesy material infants are coated in childbirth.

To Ben’s horror, it resembled the numerous coconuts he had cracked open to get macapuno.

Christine took one look at the dead infant, clutched it close to her bosom and screamed that unearthly wail only mothers can make while mourning the loss of a child. The grief is unnatural, bringing chaos to the visceral order of things. Carmen stayed with Christine the entire day, cradling her, crooning and singing in a comforting stream of non-words.

It was half past eight in the evening, but it might as well be midnight. The horror of the stillbirth left an uneasy pall in the barangay. The place was eerily quiet, the entire community shocked by the grotesque disfigurement. Carmen walked across from the house, found herself a plastic chair and leaned it against the limestone, drawing strength from it. Despite the early supper she prepared for the three of them, she felt weak, her arms and hands rubbed raw with soap and scalding, hot water. She sat there, her hands cradling her face in exhaustion. She heard several footsteps, and the distinctive shuffling sound Ben made when he walked.

“Is Christine awake, Ben?” she asked, not lifting her head. There was an audible pause, then a searing, white-hot pain. The next minute, Carmen is kneeling on the ground. Blood dripped from a cut on the side of her head, forming a congealed mess with the mud. She incongruously remembered her father’s lectures on the nocturnal dangers of walking under putrid durian trees as they would often relieve themselves of their noisome fruits during the night. Carmen groggily lolled about, desperately trying to orient herself, embroiling herself in the soil and mud with detritus clinging to her hair, an insistent ringing in her right ear.

Ben towered over her, his face a thundercloud of unadulterated fury. His left hand was empty, having thrown the rock. But anger made an unsteady aim, and the projectile only grazed the side of her head.

“What have you done?!” he screamed at her, his face flushed with rage, spittle flying from his mouth.

“What have I done?” he brokenly whispered, tears streaming down the gullies of his face.

A large, amorphous mob started to gather, agreeing with him, buzzing spitefully with the murderous intent of provoked wasps. Carmen saw the outline of familiar faces: Kap Berto who had a sprained ankle which she bandaged and tended to a few months ago, Nanay Eden with the shy bowel who she prepared a draught for her when it needed prodding, and the numerous young people on the precipice of adulthood who she helped deliver. She was intimate with most of their physical ailments, and unfailingly helped when she could and advised medical treatment when the pathology was beyond her.

Carmen’s vision blurred with sudden unshed tears, the suffocating pain in her chest worse than the throbbing headache. She breathed deeply, used the chair to steady herself and deliberately stood up, slowly rising with whatever tattered dignity she could muster and serenely faced the crowd, her countenance a study of stoic indifference. The crowd momentarily hushed, but discernible malevolence still seethed below the surface. They retreated when she took a step forward, so she took another one. Her face remained impassive, but blood from the cut in her head gushed freely now, mingling with the tears that had started to flow. The muttering horde parted, and she placidly walked through, reflexively following the flowing red path to her home.

Carmen could not count how many times she stumbled; the heels of her palms rubbed raw from constantly breaking her fall. She had shrugged off her sandals a few meters back as the blood dripped on her feet making it difficult to continue. She stayed on the path with the unhurried, restrained stride, her rigid shoulders relaxing somewhat after leaving the community behind. Nobody followed her to her home. At least, they afforded her that peace.

The graceful sugarcane greeted her with upturned leaves, murmuring pleasantly, comfortingly. They gravitated towards her, bending and twisting in the imagined wind, like iron fillings skating on top of a sheet of paper, insistently rushing to her as the magnet below. She walked with the slow pace of the defeated, mourning the baby’s demise, Christine’s anguish, Ben’s self-loathing. But above all, she grieved the loss of their rudimentary family.

Eventually a discernible resoluteness in her eyes replaced the unquenchable sorrow; she has made the decision. Slowly and with measured movements she methodically took off her clothes, keeping the rhythm of her pace. The discarded garments lay tepid in the wake of her undulations, akin to that of a moth leaving its chrysalis. With a smooth downward motion, she scooped reddish soil from the ground, kneaded it in with clots of blood and tears. With it she traced symbols on her face, down to her naked chest and stomach, continuing on her arms and legs. In a fluid gesture she bent her arms backwards, scribbling ancient text on her bare back.

Carmen knew what the sacrifice demanded from her. Years ago, her mother had done the same. And her mother before her, and the one before her, and as far as she could remember, all the women of her family. It is their duty, their sacred privilege. But this time, Carmen was doing it for Christine, for Ben, for her stillborn granddaughter. For her family. Her head rang with the clarity of her choice.

Abruptly, haltingly, as if suddenly remembering forgotten words deep in her subconscious, Carmen began to sing. She sang a heartbreaking sonata, in a voice unheard of by anyone. She trilled as the clean, airy whisper of the cold mountain air, descending from its lofty perch to cleanse the earth with mist and dew. She intoned the deep melodies of the of the subterranean caverns, calling forth the roots of the trees, plants and shrubs that connected every living thing in a single, yet impossibly interwoven thread. She hummed the odd, electrical crackle of time, as it continued to fall relentlessly towards the end. She chanted the mysteries of life and death, how one ws a conduit of the other, constantly repeating a never-ending cycle. The earth fell silent as it listened to the ancient, forlorn song.

Carmen reached her destination, opened the gate and headed for the giant acacia tree. As she started to climb effortlessly, she sang of the fickleness of the human emotion, the contrasting melodies interweaving in an unpredictable pattern of calm and chaos. Humanity was an interesting concept of unending conflict contained in a vessel of bruised flesh.

The air at the top was as she remembered it, bracingly cold and fresh. Carmen had finally completed her song. With a sudden wrenching motion, she pulled out a pulsating globe snatched deep from her chest. It thrummed politely at her.

“I’m sorry we failed again,” Carmen murmured heavily.

She cupped the orb of light to warm one cheek then the other. It purred appreciatively. “Next time we will succeed; I’ll make sure of it.”

It glowed in happy yet apologetic understanding and without warning, shot up in the air to disappear into the luminous night clouds. Two years later, Christine would give Ben a daughter.

After four failed tries, this time would be the last. Carmen could feel herself scattering. Her skin started to break where the symbols were etched earlier, taking on a dry, terra cotta hue. She was turning to dust. Swirling filaments of blue light swimming like luminous eels, escaped through the crevices in her skin to stream and eddy into the vast expanse of the sky.

Her innumerable kin who came before her lay scattered dyeing the soil red, breathed encouragements to ease her transition. She hoped she would eventually rest under the mound of igang where her mother, who had done the same sacrifice, was waiting.

She started to crumble, and as promised, kind winds picked her up towards the direction of the limestone. Carmen had always wanted to feel the exuberance of the birds who always chattered in flight, and in the moment before completely turning into red dust, she flew.