NOVEMBER 1972, MARTIAL LAW. MY MAGAZINE THE GRAPHIC, PUBLISHED BY DON Antonio Araneta and edited by noted journalist-lawyer Luis R. Mauricio, was closed down, along with other publications, except the crony Daily Express.

Staffers more radical than me were on the run, hunted by the military. Mauricio was arrested, along with two others. One had earlier joined the underground while another was wanted by the Constabulary on a libel charge. I was jobless for a time.

During those days I would visit the offices of Mever Films, owned by Johnny Litton, which was located at the top floor of the Avenue Hotel in Santa Cruz, Manila.

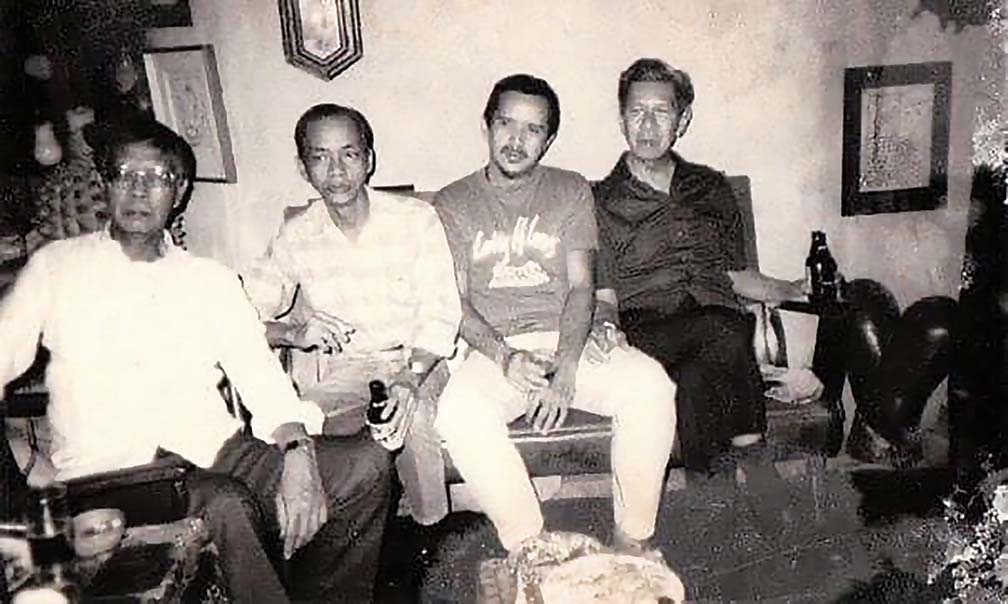

Two friends of happy memory, Frankie Clemente and Greg Marquez, worked there and I would nag them for tickets to the movies released by Mever. It was they who told me that the well-known writer Wilfrido D. Nolledo, one of the outstanding short-story writers of the 1960s, along with Gregorio C. Brillantes and Gilda Cordero Fernando (see Philippines Graphic, November 30, 2022 issue), was holed up in the hotel writing a screenplay.

Even then, the Avenue Hotel, a landmark heritage institution, had seen better days and there were only a sprinkling of guests staying there. That I was how I got to meet Ding Nolledo, as his friends called him.

We talked from time to time, and I mentioned that I had a collection of short stories the publication of which had been rudely interrupted by martial law. I expressed the hope that he would write the introduction to the new book being planned. He said yes in principle, but never got around to doing it. Then he later checked out of the hotel, and I lost track of him.

A few years later, I learned that he had become one of the editors of the Observer, a magazine of the Times Journal. Here was a chance to renew the acquaintance. He did get to approve and publish several of the articles I wrote for that publication, including a cautionary piece on the George Orwell classic 1984, for that supposedly sinister year was fast approaching.

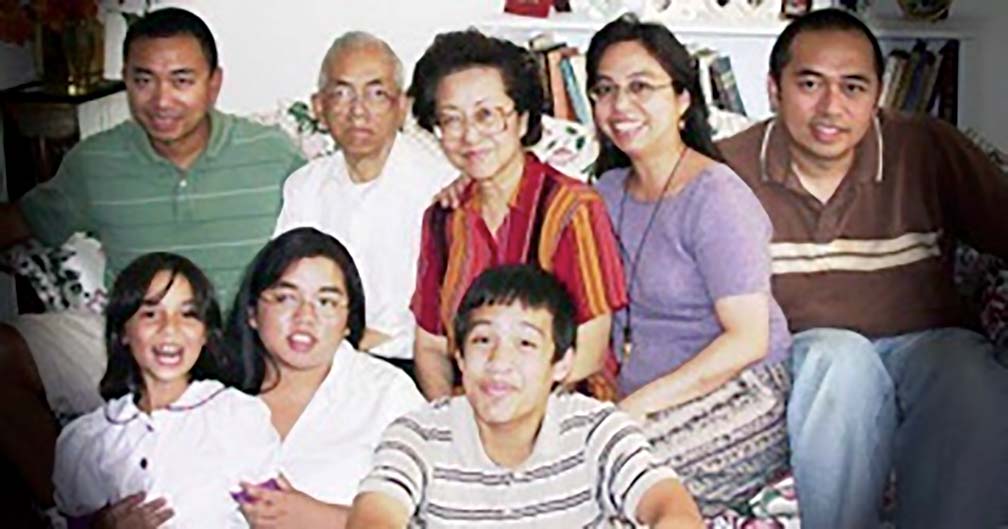

During the late 1980s, Nolledo with his family (wife Blanca Datuin and their children) migrated to Panorama City, California, where he stayed until his death in 2004.

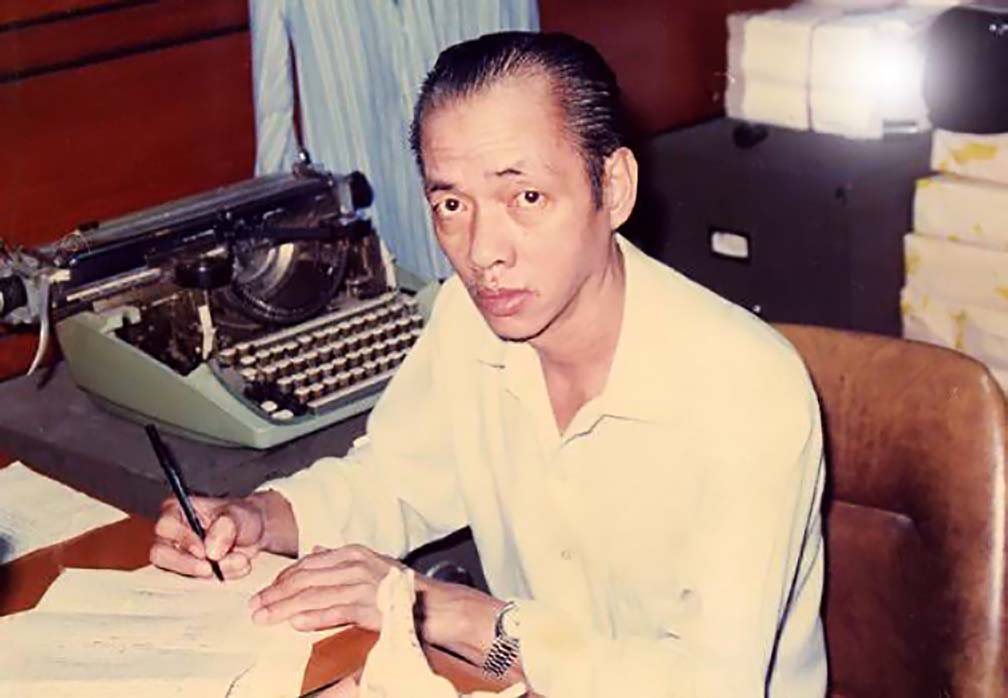

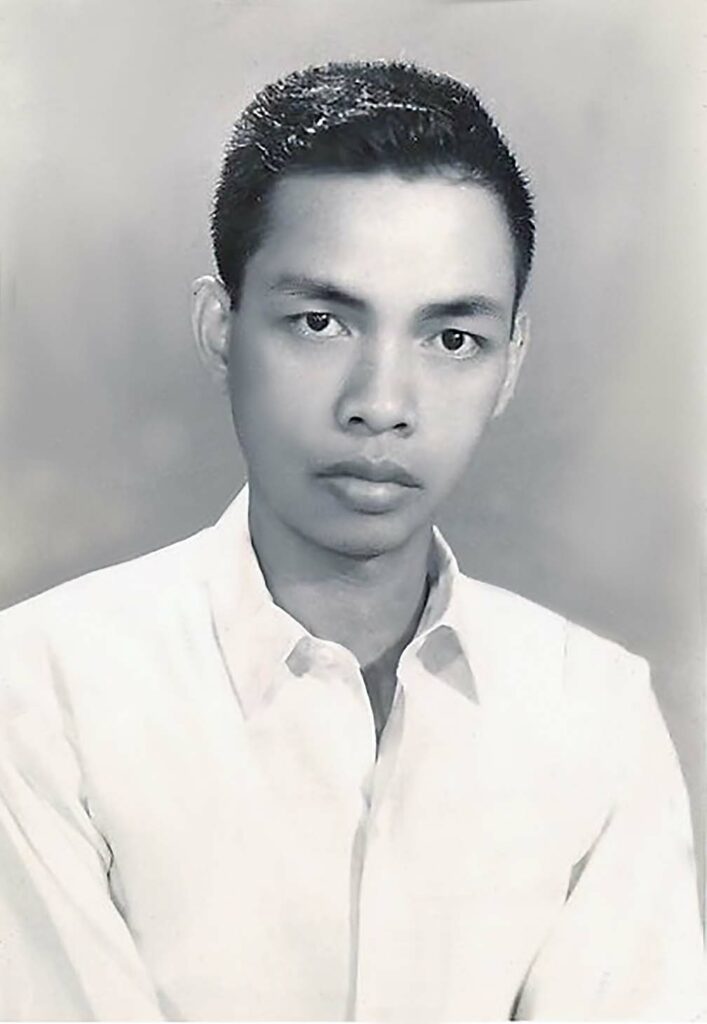

The multi-awarded Wilfrido Dayo Nolledo was born in Manila on January 19, 1933, finished high school at National University and graduated with a BA in Literature from the University of Santo Tomas (UST).

He also studied at San Beda, for that college (later university) honored him with a Bedan of the Century trophy in 2004 for lifetime achievement in literature. During the mid-1960s, Nolledo was a Fulbright scholar at the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop in the United States, became the literary editor of the Iowa Review, and a Fellow at the University of Iowa.

Nolledo was a short-story writer, novelist, dramatist, screenplay writer and journalist. He first gained attention for his short stories as an undergraduate at UST, which were highly praised but, according to the scholar Bienvenido Lumbera, “befuddled” some critics.

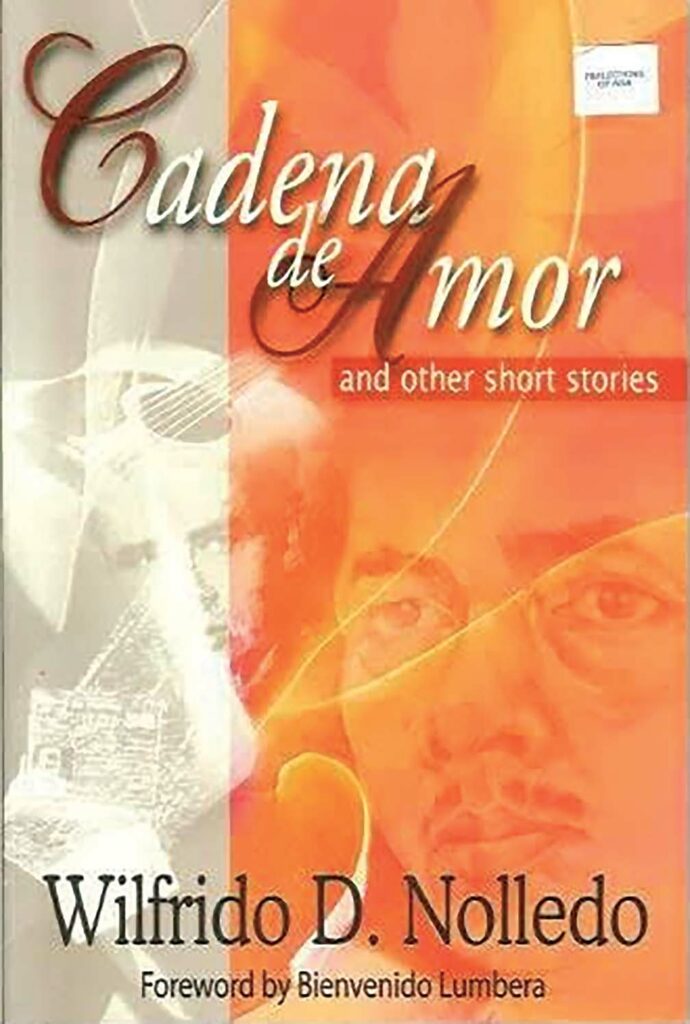

Sixteen of these stories later appeared in the collection Cadena de Amor and Other Stories (UST Publishing House), which came out in 2004 shortly after the author’s death.

“Painfully shy as a person, Nolledo was given to dark introspection and in his introversion that he related only to a limited circle of friends,” Lumbera (the future National Artist) recalled. “In the 1960s he was a short story writer but not much understood. Aware of his reputation as a ‘difficult’ writer, he was nevertheless fiercely committed to the method and style he seemed to have invented for himself, almost indifferent to complaints about the waywardness of his narratives, the idiosyncratic broodings of his characters, and the nervous style that teetered between prose and poetry.”

MAGIC REALIST NOVEL

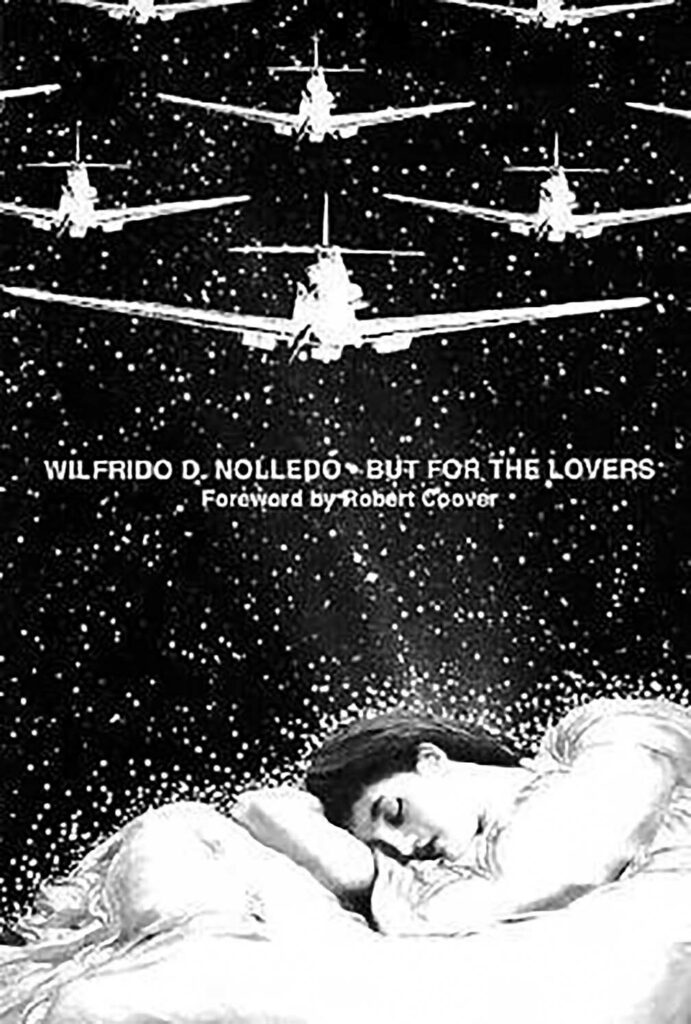

Nolledo completed three novels: But for the Lovers (1970, Dutton, New York, and subsequently reprinted), Sangria Tomorrow, and Vaya con Virgo. The last two novels won the Palanca grand prize, in 1981 and 1984, respectively.

It was But for the Lovers which was the most celebrated, and it gained for the author a following in the United States.

“Ironically,” wrote Lumbera in his introduction to Nolledo’s book of short stories, “the work that gained him near worshipful recognition from his contemporaries in the U.S. put a distance between him and Filipino readers uninitiated in the poetics of the artistic cult that claimed him in Iowa.”

American critic Jackson I. Cope, writing in New Letters, praised the novel: “Wilfrido Nolledo, well known in the Philippines for some years, has entered Western consciousness with the publication of the war novel But for the Lovers. It has placed him immediately in the company of the most interesting contemporary novelists, employers of a tradition of setting cultural myth against itself, the creative skeptics of form.”

The New York Times Book Review raved at Nolledo’s novel, calling it “stunning.” Another critic observed that the novel “experimented with magic realism long before the term was invented.”

It should be noted, however, that Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s seminal One Hundred Years of Solitude, which opened the floodgates of magic realism, was first published in Argentina in 1967 (in Spanish).

Nick Joaquin, another future National Artist and Nolledo’s literary editor in the Philippines Free Press, described him as a “young magus,” who had turned the Philippines’ war experience into a poem.

Nolledo sent Joaquin a copy of the novel, with a dedication which partly read (as I remember it) “…we have kept the faith.”

Joaquin’s copy of the book was passed around among selected friends, and I was lucky enough to get hold of it.

That was decades ago, and the details have grown dim in my memory. But, yes, there was a kind of magic to the novel with a heroine that was part Maria Clara, part nymph, and part avenging woman warrior.

But on the first page, there was a typical Nolledo pun which jolted me: Iba na ang Ibanag!” At the Avenue Hotel, I confronted the author about this. “Well,” he said nonchalantly, “I insisted that the American publisher retain all the Tagalog words.” The second edition of the novel had this description: But for the Lovers depicts a cross section of Filipinos during the Japanese Occupation and the American liberation. The cast is enormous, an old man who used to roam the countryside entertaining children, a young guerrilla messenger, the coming of the American army, and a Japanese major who views the war as a liberation of the Asian people from Western civilization. This extraordinary novel is no less remarkable for the power and beauty of the language than for the exotic and magical world it creates. Ranging from hallucinatory lyricism to documentary realism, from black humor sketches to scenes of horror and degradation, But for the Lovers is a rich complex exploration of language, history and mythology.”

Recently, Filipina publisher Mara Coson told the Graphic that they will be republishing the first Philippine edition of Nolledo’s But for the Lovers, this March.

“CANTICLE FOR DARK LOVERS”

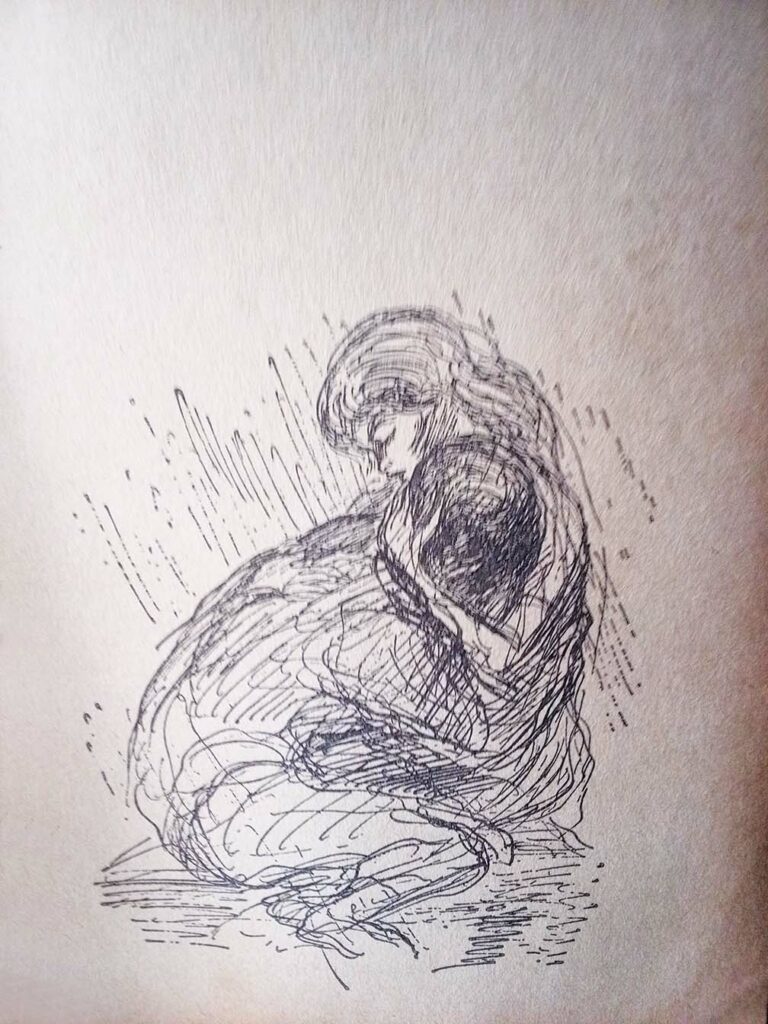

Way back during the mid-1960s, there was a magazine published in New York called Short Story International which featured stories from writers around the world, including such heavyweights as Arthur Miller, Yukio Mishima, Alberto Moravia and Muriel Spark. Some of these issues I have kept through the decades on top of my bookshelves. The covers were colorful and attractive, and sketches illustrated each story. One of them was a famous tale by Nolledo, “Canticle for Dark Lovers,” (his first name was misspelled as “Wilfredo”).

“Canticle for Dark Lovers” is a searing indictment of postwar Manila, a blend of poetry and social realism, flamboyant, Nolledo style. The hero, De Leo, is an antihero, a “gigolo, a rogue, matador and driver, a gladiator in small arenas where the ladies of the night sometimes passed their time adoring the bodies of marble- like gentry.”

De Leo is on the side of the angels but he is violent, to strike breakers as well as, in an earlier time, to the Japanese forces. His bete noir is a lusty widow, unnamed, who uses De Leo’s body and is used by him. It is a love-hate relationship. The story begins with the two making love without much affection and ends with De Leo outside her window, wounded and shivering in the rain, with the widow pretending to be unmoved by his plight.

Reread after 50 years, “Canticle for Dark Lovers” remains an in- your-face experience, perhaps even more so than before.

CADENA DE AMOR

First published by the University of Santo Tomas Publishing House in 2004, Cadena de Amor and Other Stories (with Introduction by the late National Artist Bienvenido Lumbera) is a collection of Nolledo’s best short stories.

They include, among others: “A Lily in the Sea” (1955), “Maria Concepcion” (1959), “Since You Do Not Sell Gardenias” (1959), “Kayumanggi, Mom Amour” (1960), “Home to Celia” (1960), “Rice Wine” (1961), “Harana” (1962), “The Last Caucus” (1963), “Canticle for Dark Lovers” (1964), “Amor de la Calle” (1965), “Purist, Hold Your Apocalypse.”

In the collection are two Palanca Award winning stories, namely, “In Caress of Beloved Faces” (1955) and “Adios, Ossimandas” (1960).

The title story is a haunting Nolledo tale, magic realist in its own way. Here we have a wealth of images; a procession for the dead, with a boy beating the drum; a dying old Spaniard, Gayo Labrador, dreaming about his clan’s colorful past in Spain; two quarrelling young doctors trying to save the patient; and the nightingale Ouida, one of the author’s nymphs, who is a mythical lover to all men; and the Spaniard’s past, “a necklace of pimps and princes.”

“In Caress of Beloved Faces” reads like a long poem and is probably partly autobiographical. It is a love story, and begins when the young couple surreptitiously leave their wedding and proceed to the room which will be their future home. They call each other “Dee.” The man is a lonely writer, unnamed, while the woman is named Blanca (like Nolledo’s wife). Their love bloomed in the campus, where they finally confessed their feeling for each other in the library. In the room where they will live, the couple begin to tidy up the place, settle down and get to know each other. They tell each other stories, discuss the future and Blanca says she wants to have four children. But all may not be wine and roses for the literate, sensitive couple; for the man has a “dark secret.”

“Adios, Ossimandas” is an affecting tale set in the US during World War II and begins with a foursome date at a dance hall: Sergeant Miles and Johnny Ossimandas, a shy, bemedaled, 19-year-old war hero, paired off with Clara, an American and Stella, a budding writer who is a half-American Filipina. Morena Stella manages to overcome an initial dislike of the war hero and agrees to a picnic date with him. Nothing happens except a fast embrace. Years later, back in the Philippines, married and with children, passing by the American cemetery, Stella remembers gallant Johnny Ossimandas, killed in battle (in Manila, at that) and all the young men who have died in the war with Japan, and proceeds to write a novel inspired by him.

The last story “Purist, Hold Your Apocalypse” is something of a letdown, anti-climactic considering the vivid tales which preceded it. It is a satire of a movie shoot in the US, with the woman screen-writer landing in a hospital because of an accident; her stream of consciousness while seated form the bulk of the story. It is a later Nolledo story, most likely written when he had settled down in California, so let’s leave it at that.

Nolledo’s stories read well despite the passing of the decades. His themes may be national but emotions dramatized are universal.

“Rice Wine” is one of the most famous of the author’s short stories and is at par with “Canticle for Dark Lovers.” Some would say it is his best, and it is often discussed in literature class.

Two old men of the Revolution, Santiago and De Palma, still glorifying the controversial Aguinaldo, are deteriorating in the city gripped by famine, where rice is being hoarded. Santiago is dependent on his beautiful daughter, Elena, while embittered De Palma has been reduced to selling sampaguitas. Elena is really a prostitute in a class by herself; everybody knows this except her father. When Santiago finally learns this, he goes berserk, with tragic consequences. And he spears sacks of rice with his antique sword, and the unhusked rice falls like drops of rice wine, the lambanog which blurs reality for those who do not have enough to eat.

There’s something about a Nolledo story when you’re reading or rereading it. You may get turned off by the surreal, Americanized street-smart language; the endless wordplay and puns; the name-dropping of famous artists and their works. But, as in “Don’t Sing Love Songs, You’ll wake my Mother (1964), “things turn reflective and introspective; and the hero, after a wild boys’ nights out, realizes his life must have taken a wrong turn somewhere.

COLLEAGUES CHEER

“Young authors in the new millennium,” wrote Lumbera in 2004, “whether they write in English or Filipino, whether they write fiction, poetry or drama, will be suffering a great loss if they fail to be introduced to an ‘old’ writer who resisted the mellowing aging was supposed to induce and continued to be ahead of our time.”

“Ding Nolledo’s quiet intensity often masked the fact that he stood at the cusp of a struggle in Philippine literature,” opined novelist Ninotchka Rosca. “He defied standards drawn from American literary theory and propagated by American critics. He used English as a Philippine language—one reflective of the multilayers of the archipelago’s culture and hence more capable of expressing the passion, rage and confusion of the Filipino’s colonized soul.”

Poet Alfred Yuson was just an enthusiastic, if not more so: “The stories of Nolledo will remain synonymous with seduction, wizardry, intoxication. Eloquent and dazzling are additional lauds for his trailblazing fiction since the Sixties—those halcyon days when readers and budding writers recognized the premium in language as fresh and riveting as substance it spun and wove. Oh, how we marveled at his narratives of romance, grief, heroism, failure. Thrilled to lyrically adroit, virtuosic articulation. He lives on, his powerful prose lives on—to amaze more generations of writers and readers. Bravo Nolledo!”

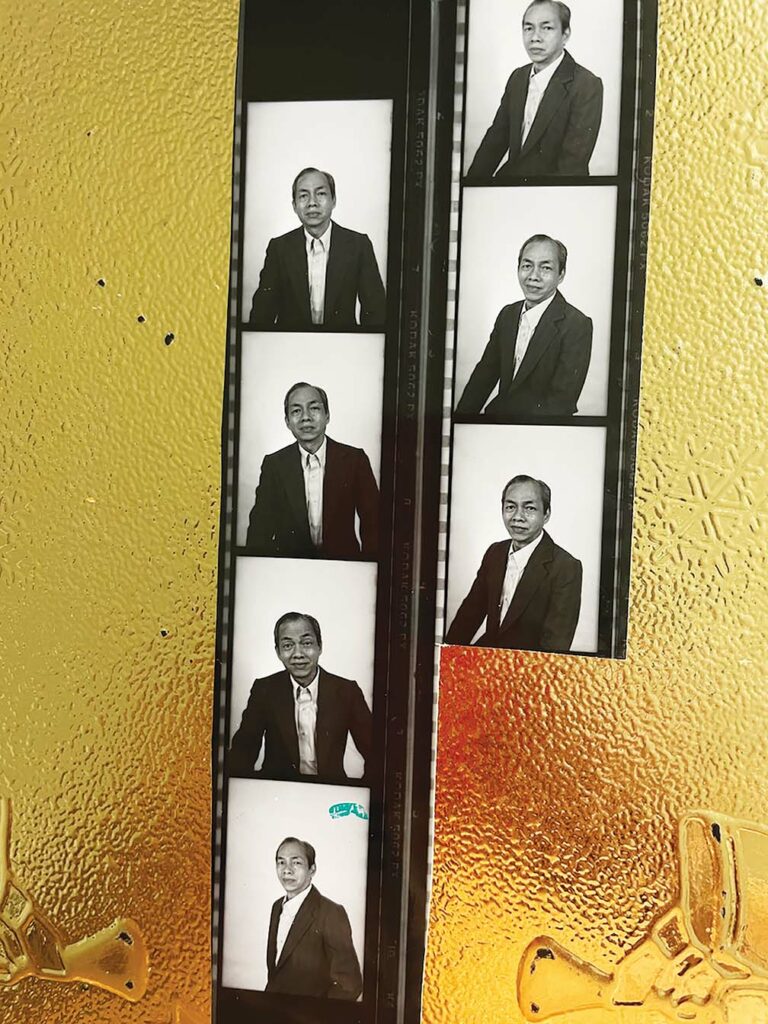

Nolledo’s legacy includes four novels, the last of which—A Capella Dawn—he was polishing at the time of his death. According to Lumbera, the writing of this fourth novel, said Nolledo in one of his last letters, filled him with “absolute joy and fury.” But he was not given enough time to finish polishing the manuscript. And so, it seems, we have been deprived of a final masterpiece.

IN MEMORIAM

Nolledo died of pancreatic cancer in Los Angeles, California, on March 6, 2004, at the age of 71. His widow, Blanca Datuin-Nolledo wrote a poem, “The Other Half of Me,” a few days after Nolledo’s funeral.

Included in her book, Rekindling Love (sold online on Amazon), the poem was well received by religious circles in the United States, among them the LA Archdiocese Director Rev. Michael Perucho of the Vocation Ministry.

The Other Half of Me*

By Blanca Datuin

Beneath this mound of soil

lies the other half of me, in wait

for this self still walking ground

trekked together before now dotted

with only a pair of footprints.

I lay roses upon tombstone

in ritual of love and pray:

please God let him who loved

You continue to love, and

You who loved him in his life,

Continue to love him evermore.

I sit awhile on the grass, well of tears

at last comes unabated, unashamed as,

desolate, I speak to the other half of me,

retrieving images of past highs and

lows of our together life:

the poetry we fed on that filled the soul,

as our empty pouches laid concealed in

richness of our dreams; hurts we unknowingly

meted out to each other. What are aches and

pains for---that gnaw at layers of grit---

if they cannot unearth the Phoenix in us?

Shared anguish against inequity, shared agony

over cauldrons of war, shared rage against

injustice, shared dreams and hope for peace.

Such passion and ecstasy, anger and humor,

all inextricably bound in the mingling

of life’s laughter and tears.

This self must go on through motions of life,

Though not quite whole, not quite hale,

for the other half of me is gone.

How strong she is, people say. If only they knew…

Tasks must be finished, whatever heavens ask,

but there is an end to every journey, I, too well know.

Little drops of rain moisten soil on my other half.

Cold tomb looks up at endless blue above,

and earth sucks tears of vaulted sky.

I beg the other half of me, acquiesce in wait for

Giver of Life to fill tomb’s empty space by your

side and make the we of us together again.

– bdn, 2004

*In memory of Wilfrido D. Nolledo