Melanie thought she should walk. She didn’t want Mrs. Guzman to see her in a tricycle. It embarrassed her. On FB Messenger, Mrs. Guzman asked if she was coming by car. Of cour,se she didn’t have a car. Why would Mrs. Guzman think she did? On a call center agent’s salary? Call center agents, contrary to what many believed, didn’t make much. It was more than enough for a college dropout, yes, let alone a high-school graduate, but not enough for a serious professional, and Melanie always thought of the serious professional she could have been. She could have been somebody, somebody with a car, a car and a sweet life, had things been different.

So she walked. It was hot and taking a tricycle would have been the sensible thing to do, but she walked. Mrs. Guzman probably had a car, of course, she did. No wonder she assumed Melanie did as well. If she had a car, then everybody else must have a car. It’s like dumb people assuming everybody else is dumb — one sees the world through one’s dedicated lens. The guard at the entrance to the subdivision asked Melanie for an ID. She showed her old college ID. It was a good university, one of the very best, actually, absolutely nothing to be embarrassed about. The guard must have thought her very smart.

And she was. Melanie was smart. Everybody knew that, everybody said so. Her grandmother knew and said so. Now Melanie wondered, however, if the belief came before the fact. Maybe her grandmother willed her to become smart, maybe hers was a conviction born out of love or desperation or desperate love or loving desperation. Maybe it was loving despair, despairing love, love for despair? It was a kind of love regardless, a kind she wished she hadn’t known. But what choice did she have? Whatever. What’s done was done et cetera et cetera. Whatever, for Melanie had moved on. But then again, she had been so smart and look where she was? That kernel of a kernel of a thought made her ache quite a lot inside, and often, too.

Fortunately she didn’t have to walk far. There it was, an okay-looking bungalow, 137B Lot C. The knickknacks strewn in front (a carelessly looped garden hose; a yellow, overturned bucket by the faucet that said Roces Margarine; shoes and slippers, including a couple of Nikes) displayed an air of abandon that bordered on chaos, but it was good chaos, just enough to say Happy, functional people live here. We don’t care and we can afford not to care because all this is ours. The tableau lacked the sterile, suffocating beauty of a furniture store catalog or a studio unit designed for a maximum of two people, no pets, females only, working — each could only ape genuine domesticity.

No car, even though there was certainly space for a big one.

There she was, Mrs. Guzman, standing by the door, a kind smile on her face. Mrs. Guzman, happy and functional and looking quite motherly.

Melanie introduced herself, adding a quick “po.” She didn’t want to sound rude.

“I have been waiting for you. Come, come!”

The house looked different inside. Class, Melanie thought, eyeing the large LCD television (Philips), the coffee table topped with thick glass, the shiny parquet flooring, and the iPad on the giant couch. Wait, two iPads, just lying there, just because. Mrs. Guzman inhabited a very sweet world. One would think otherwise looking at her ratty house dress, but then again, she simply could afford not to care.

Unlike Mrs. Guzman, Melanie’s grandmother wore fashionable ternos and never let her hair go gray. But that was because she couldn’t afford not to care. Sometimes, she told Melanie, that is all you have.

Melanie followed Mrs. Guzman to the kitchen. She was offered coffee (Nescafe Gold) and, quite incongruously, some boiled saba. Mrs. Guzman mentioned something about hypertension, old age, and potassium. Nothing about saving money. So the old woman took care of her health, good for her, unlike Melanie’s mother, who reportedly chugged Coca-Cola like it was water. Ah, yes, her mother. That woman who loved to eat, who lived to eat, who — what else? Ah, yes, she’s dead. Had been for quite some time. Ate herself to an early grave. Melanie had almost forgotten about her. She probably should think about her a little bit more, considering that she’s the reason Melanie was in this house in the first place. She probably should think about her a little bit more considering the trouble she took getting here. Quezon City to Calamba, Laguna. It was her day off, too. Melanie loved to sleep it off. She worked a graveyard, shifting schedule and it was physically taxing. Melanie should have slept this one off.

Because what’s the point? she thought. Seriously, what’s the point? She asked and asked but she never didn’t want to figure it out.

Better to get this done and over with.

Mrs. Guzman began by asking the usual questions: job, education, boyfriend/husband? She said it was too bad Melanie didn’t finish college, but told her not to despair, she could always go back. She said it was impressive how she made a life for herself. She said marriage could wait, she was young, she was pretty, she looked put together. She said Melanie was lucky, still lucky, having had her grandmother, lucky regardless, no doubt. The old woman said things and things and things, circuitous cutting through the fat; oh, my God, get to the point, would you? It’s called manners, Melanie, it’s called concern. It’s called motherhood.

“I am so glad you contacted me, that you came. Think of me as your second mother.” See, it’s motherhood, Melanie told herself. “From now on, I will always be here for you.”

But she has her own kids? “Thank you,” was Melanie’s weak response.

I have a mother.

“Your mother…” Mrs. Guzman weighed every memory, every word. There was no need for that, though. Melanie knew enough of the story it was pointless to pretty it up. The whole affair was pointless, from the very beginning it was.

“She abandoned me.”

“I suppose that’s the way to put it.” The old woman looked genuinely hurt. She motioned for Melanie to sit on the couch in the living room. “We’ll be more comfortable over there.”

“Thank you.” Melanie moved the iPads out of the way. I need to get one of these, she thought. “I came, Ma’am, like I said on FB… I don’t want to bother you or anything. I’m here because, well, Lola died last year. She had a stroke.” Melanie looked at the plate of potassium in front of her.

“I’m sorry to hear that. It’s tough being alone. But you’re lucky still you had your grandmother. She took care of you when your mother wasn’t around. She was a good woman.”

“Everybody said so.”

“I’m sure she was. Now… about your mother.” Mrs. Guzman struggled. Melanie thought she must have been a good woman, too to feel like that, to feel for a stranger.

“I think I should start by saying that she, too, was a good woman. Please don’t ever, ever think otherwise.”

“She abandoned me.”

“Yes, unfortunately, she — we… we are all flawed.”

“So why…did she abandon me?”

“Why she did what she did? I don’t know. People do things sometimes.”

Would you have done what she did? Melanie wanted to ask. She didn’t want to sound rude, though. Later, on the way home, she would regret that. She really should have asked.

“What I do know and what I can tell you…we were friends, you see? I think the embassy told you that already.”

“Yes, a woman there gave me your name. That’s how I found you.”

“The Filipino community in Nigeria is very small. We try to look out for each other. Like family.” Mrs. Guzman smiled. “Your mother, we called her Beauty.”

Melanie was reminded of the pictures. They had been tucked away in her grandmother’s belongings, useless and forgotten. Her grandmother must have stopped looking at them way before the suspicions gelled. There comes, before intuition, something more powerful, more rudimentary. It’s when you stop caring, or when you finally admit to not caring. These pictures, unearthed after her grandma’s death, had the same perpetually young, meticulously made-up, but somehow hardened face, with a smirk that mocked and hated. Maybe it was true what her grandmother said: her mother never forgave.

“She liked to dress up. She loved to dance, to sing. That’s how she met your father, at a teachers’ dance.”

Melanie never thought about her father. It never bothered her. He could be anyone but her mother — you only get one mother. The question is, how many do you need? She was surprised, however, to learn about that side of her mother. Beauty. She saw once again that unforgiving face. Beauty. But a face like that couldn’t possibly dance, couldn’t possibly sing. Besides, her grandmother said, a face like that couldn’t possibly dance, couldn’t possibly sing since it spent all its life hating.

“The attraction was immediate, I could tell. I used to tease her about it. They got along well because they’re both Ilonggos. They would speak Bisaya, just the two of them, they didn’t care about anybody else.”

“She didn’t know he was married?” Melanie asked.

“At that time he wasn’t married. He had a fiancée back here in the Philippines, but he never really talked about her. I think they were betrothed. So I encouraged Beauty…she loved him, he loved her. It only made sense for them to be together.”

“And then he disappeared.”

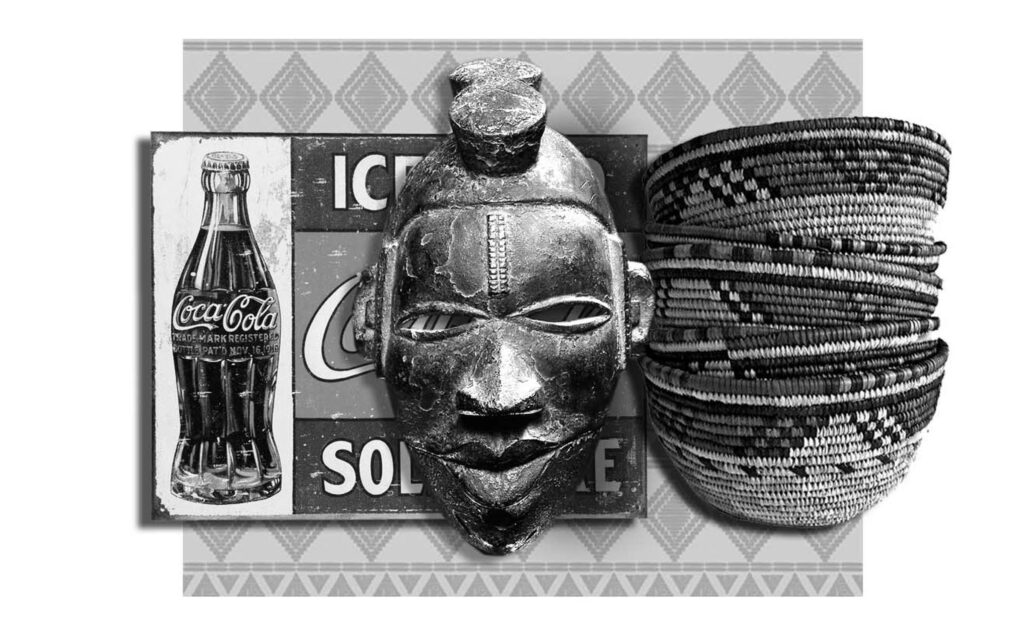

“He came back home…didn’t renew his contract. You have to understand, Melanie, it wasn’t easy for any of us. We were assigned in Sokoto, far from the capital. There were no roads. The water was unsafe to drink. Muddy — and the worms! We’d rather drink Coke. You don’t get cholera from Coke. And our students — would you believe they came to class barefoot?”

Her grandmother said that her mother spoke in her letters (this was before communication evaporated altogether) of truckloads of boys and girls — twigs with bellies the size of basketballs, blue-black skin glistening with sweat, giving off a dark, aboriginal odor that could only have come from bodies born and bred of the continent — being hauled away from their mud huts and pet lions and maliciously suspicious parents to receive an education. To be fed and bathed. To be salvaged, to be stripped of volatile tribalism and evil magic and clad in the fresh new garb of western civilization (courtesy of some very nice brown people), being the future of the country and all. And I thought the Philippines was bad! her grandmother would exclaim, clutching a gold-plated necklace and rolling her eyes in theatrical disbelief. We are poor, too, but not that poor!

“But the pay was good?” Melanie asked, needlessly. She knew it was good, her grandmother told her. She would tell her again and again to drive home the point of her mother’s absence. If she was here, you and I could have everything.

“It was, it had to be. The…inconveniences…you could live with those. I mean, I grew up in the province myself. I grew up poor. Which is why when the opportunity came, when I heard that Nigeria was hiring teachers, I took it. I didn’t know anything about Nigeria. Or Africa. But I had to get out of our country or my family and I had no chance. Nothing. I was a public schoolteacher with three kids to feed. My husband was a jeepney driver. There was no chance.”

Look at you now, Melanie thought. You are very lucky, way luckier than I — my mother and I, my mother and my grandmother and I could ever be.

“The inconveniences you could live with. Not the loneliness, no, not that,” the old woman continued. “I, for one…the first few months I cried myself to sleep. Your mother —”

“Maybe she did, too.”

“It was tough, hija.”

Life had been hard for Melanie (and her grandmother), but it was hard for her mother, too! Life is an equal opportunity sadist, so what? All is forgiven, moving on. Nigeria for those lucky teachers from another Third World country wasn’t an endless party (contrary to what her grandmother said), more like a terrifying sleepwalk through the never-ending corridors of failure and expectations. Melanie imagined her mother in that far-flung pocket of desert and human disaster, left leg gangrened beyond recognition, stuffing her stupid fat alabaster face stained with tears and runny mascara; her beady eyes, also stupid-looking, deathly still and glazed with apathy and resignation. But it never came, that booming internal voice, the great shift in emotional vector; or that warm wash of clarity, top to bottom, to kiss the demons good-bye — this is where it was supposed to come, for the real moving on. But it never came. The mind was sludge.

Because what exactly, she asked, and wanted to ask Mrs. Guzman — what was hard exactly for her mother? After all, she would rather live with it than with her own mother, her own daughter. When you make a decision, well, you better damn be ready for the consequences. Her mother sure was ready and willing and, boy, did she stick to it to her grave. It must have been worth it, like the last slice of cake or liter of Coke she chose to ingest before being comatose for the last time. The sweetest of sweets to kiss the demons good-bye.

It must have been worth it. Melanie tried but couldn’t quite connect the forgotten face of the old pictures and the faceless, ashen thing lying in the morgue in the pictures the good people of the embassy sent her. These pictures, she thought, had to be as empty a formality as the message of condolences that came with them. She died eight years ago. So what? We are very sorry. So what? We couldn’t contact any family. So what? Where were you all these years? I don’t know. Where was she? No, those pictures didn’t make her feel anything. No, she’s not asking who stopped writing first. The fat bitch in Africa or the fat bitch in Manila? It didn’t matter. Her grandmother needed her mother, and her mother needed Melanie, and Melanie needed her mother, and then the daughter became the mother who couldn’t mother her daughter because of her mother. And then nobody needed anybody anymore. Round and round the idiotic carousel went in her head, round and round — “Did she ever talk about me?” Melanie — no, another Melanie, suspended in the background of her consciousness, armed with mysterious, ravenous questions; as stealthy and as wicked as savannah snake — blurted out. The question wasn’t meant for Mrs. Guzman or anybody else. Something like that you push down. Saying it out loud makes it evil. But this newborn Melanie was insistent. It had hovered and waited patiently (for how long?); it peered through the cracks, squeezed itself through, and finally, it took its turn.

“I think she mentioned you…once. I don’t really remember. When she came home after her first year in Sokoto, I didn’t know she was pregnant. Nobody knew. So she had you in the Philippines — I think you know the story. Your grandmother must have told you. She couldn’t have you in Nigeria, her being unwed and all. The country was — is predominantly Muslim. Very, very conservative.

“ A few years later, I was transferred to a school in Lagos, the old capital. We tried to keep in touch but it was hard back then. No internet.”

“These things… nobody told me.”

“I’m sorry, hija.”

To live or to mourn. To live to mourn?

“I have pictures of the burial.”

“From the embassy? Well, that’s their job. Please don’t be too hard on yourself, hija. Look at them when you’re ready.”

“I have looked. Many times.” She paused. The pit of her stomach burned. “My mother died alone, did you know that?” The words had materialized before Melanie realized what was happening. She pushed the rest deep down she didn’t want to be rude. But then what’s the point of not being rude? This soul-slicing exorcism, it better be worth it. This is all I have. “Her body was in the morgue for two months, and when nobody came, they buried her. There was no one there to mourn, to send her off. Just a bunch of Negros and an embassy representative, that’s all. And they cut off her leg. I know she was obese when she died, but the corpse looked really dry.”

Mrs. Guzman shifted in her seat. She looked unhappy. Melanie wondered what she saw: Beauty or herself lying in that morgue, because no banana in the world could save her. Poor lady. And a good woman, too, who offered to be Melanie’s third? second? mother! Mrs. Guzman reached for a saba, taking her time to peel it and distract herself and make her life sweet again.

“I wish I could tell you more. I wish….” Mrs. Guzman’s voice faltered, refusing to thaw and shape thoughts, thoughts that wheezed by and vanished down the bogs of memory. “I’m sorry, hija. I am old. I have forgotten so much.”

To forget. Such delicious luxury! It wasn’t clarity (Because clarity, thought Melanie, quite frankly, clarity sucks); it was better. It was choice. Her mother’s choice to leave her behind because it meant leaving behind her grandmother. Her choice to not be a mother herself because then she didn’t have to be the daughter, the perpetually pained, perpetually saddled daughter, always good but never good enough, to whom much was given and much was taken away…by the very same person. Sweat and sugar and the blue-black stump where a limb used to be and the soulless stare and the puffy death mask of a miserable clown. All this in Africa. Africa, mother of all. Life, destroyer of life. I come home to die. I who couldn’t look death in the eye. Mama Africa here I am. Melanie’s mother came home because, her grandmother’s voice echoed in her head, sometimes that is all you have. And yet — the woman it seemed it felt was never dead and gone and quiet; but dying, always dying. Unsated, gorging on what little peace her daughter had — suspended in matter, embalmed in the mind.

“Oh! Have you spoken with Angie? That’s Angelica Alvarez. She knew your mother,too. I think she stayed in Sokoto with her when I left.” The old woman’s tone was more eager than conciliatory, a bit of an overplay. Her childish excitement was almost offensive. The naked saba, poised in the air, looked ridiculous. “I can give you her number. Would you like it?”

Like a good girl, stupid banana inhand, the old woman waited patiently for a response.

It would take time. Melanie swirled in a vat of things and other possibilities. All of a sudden, I have too much. It’s too much. Too much, and yet not enough. She strained as more words, the little demons they were, pulsed and pushed through, past stories and versions of these stories, past love and granny. They headed for her mommy. Mrs. Guzman started eating the banana, immersing herself in a peace that was both disconcerting and pitiful. Melanie knew she couldn’t afford that. Unlike the rest of the world, she couldn’t sleep this one off.