I

No one can forget that red banca. If anyone were to ask how it looked, no one on our island would be mistaken in describing such a banca. Its color resembled the fresh blood of a butchered pig, and it was quite large, capable of carrying up to twenty people. However, its irritatingly grating engine seemed to shake the entire Dilaya island whenever it arrived. Our fathers often likened the red banca to the noisy limestone-quarrying machines from the adjacent island. I had heard this comparison repeated in my mind numerous times; the red banca never arrived quietly on our shores.

The elders of our island harbored a deep-seated dislike for the red banca, even though it only visited our shores once a year. One of its most vocal critics was my Lola Tasing, my mother’s mother. She would say, “Here comes the machine, a chuckling demon,” in her usual sandpapery voice. She would then close the Bible and stir her coffee in a mug on a scorching mid-morning. Her fancy magic mug, similar to those used by most of the Dilaya residents, would reveal the face of the Kapitan below the all-caps word “vote” when warm water was poured in. Once the comical face of the Kapitan, with his trademark gap teeth, had disappeared, she would take her first sip.

No one can measure my Lola Tasing’s abhorrence of the arrival of the red banca on Easter Sunday. “Puyra gaba,” she said and incessantly made the sign of the cross and kissed the rosary thrice. “No fear from God!” Then, she repeated her words of supplication once again since the morning I visited her. She explained that she must repeat them for these prayers to come true.

But to the majority, this was a momentous event that needed to be prepared for and be celebrated. They say that those who ride in the red banca need to be showered with offerings. If the day is sunny on their arrival, people on our island should escort them with hoary-looking umbrellas. If it rains, boots are ready. Once they enter each house, they must be served with delightful dishes. Everyone in Dilaya would anoint their dirty kitchens’ air with the oil from fried garlic and onion, and from the fat of deep-fried chopped pork. Aside from the fried kitong, grilled pugapo, and adobo, they would clear the table for tinola, and every neighbor would swear and boast that they had used their most stress-free, free-range, native chicken from their backyard. What else was lacking? Fruits. Last year, Nang Rosa and Nang Lina’s families got lucky when they displayed sugar apples, jackfruit, and marang, which all came from the adjacent island. The guests even carried several bottles of tuba with them.

Nobody argued what was really the best fruit to offer and the best food to prepare whenever they came. All we knew was that Dilaya’s annual event would break the monotony of what was on our daily meal: dried fish, dried fish in vegetable soup, dried fish on champorado, dried fish in sarciado, or just the scent of dried fish and a warm plate of corn rice. Paklay, made of julienned pork and beef innards, also vanished in every bowl for that very day. My uncle loved to serve it with pineapple and bamboo shoots to the bowls of our island’s never-sober-men. The deep-fried salted pig intestines, ginabot, also vanished once a year. We people on the island rarely ate the meat of goats and cows because every bit of it, including its bones, were sold in the city. We made use of what remained on the chopping board and slaughterhouse. Lola Tasing said once that these dishes were made not out of creativity but rather the hard life found in a clay pot.

Many years ago, when these men hopped out of the red banca, their very first arrival on the island was both a mystery and a wonder. Everyone on the island stopped what they were doing: the men put down their sewn fishing nets, those who were climbing the coconut trees came down, and women left their dishes unwashed. Everyone gathered around them and murmured like crickets at the setting of the sun. What they saw was something novel to them: tall, neatly dressed, with fair complexion, blue eyes, and hair that glittered like gold. They looked like gods in their beautiful clothes, squinting in the sun.

“Good afternoon, everyone!” said Kapitan, our local leader who held authority over our small community for almost a decade now.

“Good afternoon, Kap,” was the simultaneous response of some of the residents.

“I am here together…with my friends who are…” He looked at his secretary who looked like him: old, gray-haired, and barrel-chested; no, his body was almost like a propane tank. His secretary whispered to his ears. “Ah, yes, yes!” shouted the Kapitan, “they are Kano!” The fuss got louder. “They are having a special kind of vacation here in Dilaya. That is why…” He paused, which he always does. “I am greatly happy…that we finally have tourists! But, my dear friends, they requested…for something. They…” The people waited, which they always did every time Kap spoke, “are also looking for someone to marry.”

The noise got louder. “Oh, my god,” a quick cry from our neighbor Jennifer, whose husband died from a lightning strike. “Pick me, Kap. Pick me, Kap. I already lost my husband.”

“Me, too, Kap!” another quick response from another woman. “I am also single. I am very…never mind, Kap! I am single. Marry me, Joe. Hey, Joe! Me!”

“Wait, please, please listen.” He signaled them to keep quiet. His voice was stronger now, almost shouting. “Forgive me, but…they don’t want…” He gave an unnecessary three-second pause again. “Adults.” And the clamor got louder.

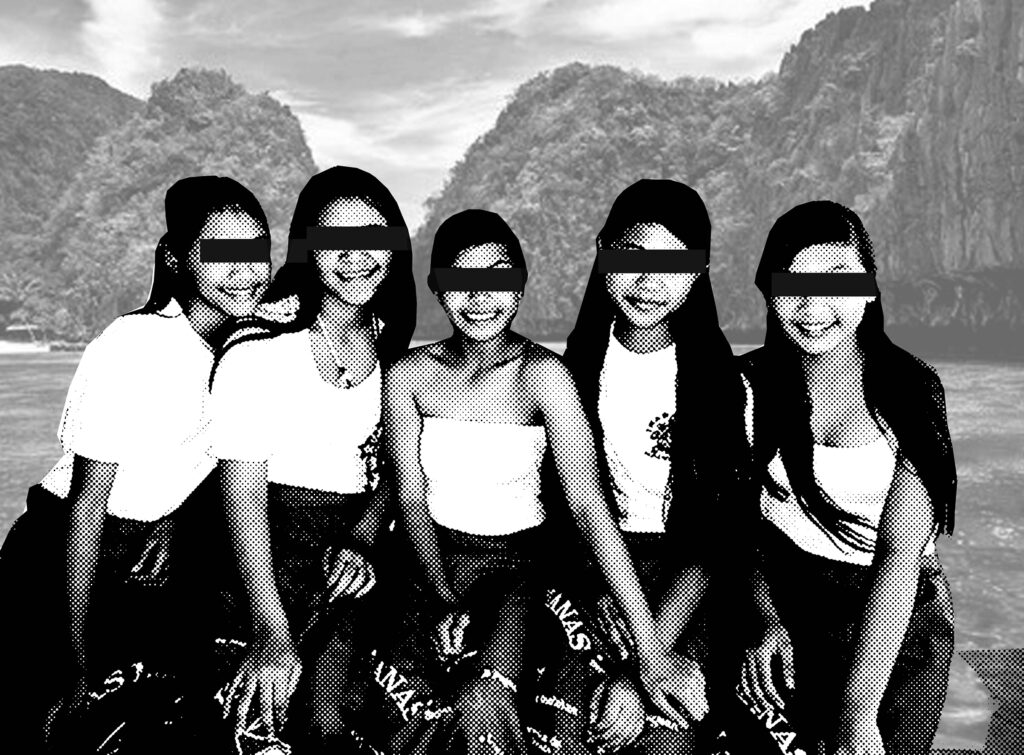

The Kapitan waved his hands. “Listen, everyone! Listen! They are looking for girls…” He paused. The following words were crisp. “They are looking for sixteen-year- old girls.” And the surrounding slowly hushed. It left most of the residents’ mouths open. They all just stared at one another.

So, are you ready?” said Mama Amor, while she combed my curly hair. I did not answer, and continued to read the termite-infested Merriam-Webster dictionary. “Wait a minute. Quit moving! I have not reached one hundred yet!” I could smell the pungent odor of ginamos from her hand. “Ninety, ninety-one…Never an unkempt hair for a girl. Ninety-two.” I just sighed, closed the book, and threw it to the corner where the heaps of books written only in the English language are placed.

Beautiful women have straight hair, she always emphasized. I blamed the sachets of shampoo she bought which had models with straight and shiny hair. When I told her that anything straight is dull, she pinched my ear.

“Ninety-eight, ninety-nine, one hundred!” I exclaimed. “It’s finished, Ma. Could you stop it? My scalp hurts! You know it wouldn’t straighten.”

I stood up and moved far away from her. Outside, my brothers played hopscotch and bato lata, laughing.

It took a few minutes before she responded. “Inday, don’t be scared,” she said, as she extended her arm to grab another book. Now, it’s the Bat-Byz, number 3, Grolier encyclopedia this time. “Their arrival this Sunday will take us out of here,” she continued. “Look at Nang Lauring’s family.” She kept telling me about how our neighbor was able to purchase a new and sturdy fishnet and a fridge taller than Mama Amor. “Is it really that tall?” I asked, opening my arms. “Yes, that tall” Mama Amor replied.

News had spread that Nang Lauring’s daughter, Rona, now living in a country with snow, snowmen, and snowstorms, would be sending money back to her family. We learned she has a job now. We learned Rona knows now knows how to use a computer. We learned she’s in the computer. However, no one from her family saw even a photo of her working, using a computer, or in the computer.

Nobody had forgotten the day when Rona was chosen. They prepared grilled squid, the largest they could offer, and added pancit canton with quail eggs that amused the tall men. And, of course, the staple roasted pig was cooked to perfection: soft, juicy, and with skin so crunchy.

After all, Rona was beautiful—tall and fair-skinned. Her cleavage was often exposed when she wore her V-neck blouse, always subtly moist and shiny. Her family also made sure she was dressed well, thanks to the branded surplus clothes they received quarterly from the city. I would say she’s intelligent, too. She had more books than I. Thanks to Nang Lauring, who diligently took most of the books from the red banca as it docked on the shore, she had gained a better vocabulary than her peers.

Nobody complained when the tall Kano, who could perhaps touch the sky, chose her. It was obvious that she would be selected. The Kano must have been impressed by her room walls adorned with countless awards, ribbons, and medals. Then, this question finally coalesced in my mind: What if I were chosen this time? I bet the entire neighborhood, armed with their fishing spears and bolos, would storm the Kap’s house— the only two-floored house on our island that wasn’t made of bamboo slats and cogon grass—and raise their grievances.

I saw Mama Amor approach the fresh palm fronds shaped into a cross. She touched it, then glanced at me, her eyes looked like the Espiritu Santo had whispered something to her.

“Don’t tell me, Ma, that you prayed to God that I would be chosen?” I whispered.

“Inday” her voice was penetrating. Mama Amor then made the sign of the cross three times. “This is what your father wants. You know that we are struggling financially. We are already struggling to provide for the needs of your younger brothers.”

I wanted to disagree with her, but Mama was right—we, young girls on this island, needed to prepare ourselves for the red banca’s arrival. I just bit my tongue, hoping no words would escape between my teeth. But when I saw my four younger brothers, I couldn’t help but reply: “You shouldn’t have added more kids!”

“What can we do if your father thought it would be another girl,” she said with a sigh, touching the bruise on her arm. “Alright, just be good this Sunday, okay?” She forced a smile, noticing that I was staring at her arm, and then touched my cheek. “It looks like there will be a popping pimple, Inday. Please wash your face with the laundry soap I bought. I heard Lilia’s daughter used it.” She paused when she saw me roll my eyes. “Look, Inday,” Mama Amor paused and suddenly fell silent. She was now gazing at the moon, then at her moon-shaped bruise. “We are no match for our neighbors, who are already flawless and fair-skinned. Now, go. Wash your face.”

The moon’s light shone brightly into our room. Perhaps, its light embraced the entire Dilaya, with its tiny houses and homes getting smaller and smaller. As she approached the doorway, our bamboo slat floor beneath her bare feet emitted a loud creaking sound. She leaned closer, and said, “Before, young women used to hold their wedding party on that hill.” Her voice joined together with the perpetual songs of the cicadas. “But that was then.”

Dilaya had trained girls to enter through certain thresholds, including keeping their bodies clean, free from scars and wounds, and maintaining the sweet scent of their skin. I remember asking Mama Amor why she wouldn’t allow me to play outside with my brothers, and she quickly answered, “What if you get a scratch or gash on your knees? Our clan doesn’t even have a fair complexion. But this is your time, Inday. Stay home, and wait for your time.”

My time.

On the island, time only seemed to exist when the mothers scream out their sons’ names (usually their fathers’ names), believing that names are not just a combination of letters, but an extension of stories that must be passed down. Screaming their noble names only meant one thing: time to go home from a long day of play. However, the older we girls got, the more we dependently check the time and day. As the people on our island had learned to mark the time according to the season for fishing, and harvesting of corn, ours have been marked by menstrual blood. Our bleeding is celebrated. It’s time for us to be harvested. It’s time for us to be afraid.

I didn’t join the via crucis. Instead, I ventured to the nearby mangroves, and the first thing that caught my eye were the blazing torches carried by the other sixteen-year-old girls. The flames flickered and danced against the darkness of the night, casting eerie shadows around them.

“Good evening,” I said, my voice trembling with anticipation.

The light from their torches seemed to pierce through me. Edna, one of the girls, responded with a nod and a faint smile. She still had the full moon-shaped bruise on her left eye after her father punched her last week for attempting to leave Dilaya. The other two girls she was with just stared at me, waiting for my next words. I cleared my throat, remembering the secret invitation they had given me exactly a month ago. I clenched my fist, took a deep breath, and spoke with unwavering determination.

“I thought about this for weeks.” I said, making sure not to show any hesitation or uncertainty on my face. Edna’s smile widened as the evening waves crashed on the shores, almost drowning out her response. I continued, my voice gaining confidence. “I will join in your escape from this island.”

Edna handed me a torch hidden among the large rocks, and Joanna lit it. Joanna had lost so much weight since the last time I saw her. I heard that her parents had forced her to fast and eat only vegetables. “Fat girls aren’t attractive,” her father would sneer during tagay.

The musky, charcoal-like smell started to fill the air. As I stared at the flames we were carrying, I recalled a story I had read somewhere about a man who stole fire from the gods and gave it to mortals. This time, we would rewrite the story, and the thieves of fire would not be a man.

I could still remember the day we talked about the great escape. The April sky was cloudless, and the mid-morning air was already hot. The sands coated our soles, and the drifted twigs and shells cracked underneath our feet as we walked briskly. “Jen-Jen…” Martha suddenly said, slowing down and eventually stopping. Martha’s hair became shinier. Her mother usually went with my Mama Amor to the public market to buy coconut milk for her hair. Every night, Martha’s mother would rub coconut milk on her hair.

I looked at her. Waiting for her next words. Joanna’s expression was distraught as she spoke. “She made a deep cut on her face using her father’s pinuti.” Jen-Jen’s family was greatly dismayed by what happened. They knew that Jen-Jen would no longer be chosen by any foreigner, and no malunggay poultice could heal it without leaving a scar. “She wanted to break free from the yearly tradition of the island,” Martha added. Our pace slowed down, and the surroundings started to get dark. As we walked, the surroundings grew darker, and the shadows of the trees, plants, posts, and huts appeared more somber.

Before the day ended, I thought of Angel, who, at nine years old, used to fold papers to make boats. She would release them onto the water, but the sea always devoured them. Teresa, who was eleven, always folded paper airplanes. No matter how earnestly she blew on the plane’s tail to make it fly higher, it always landed on the seawater, devoured, swallowed, gone, claimed by the sea. Angel and Teresa were just among the few who had learned something: escape is never easy.

II

No one cooked binignit or biko when Friday arrived. “Let’s tighten our belts, especially Sunday is fast-approaching,” my neighbor explained to her son, who was asking for binignit.

The island’s silence was replaced by the airing of the Siete Palabras from the Kapitan’s house. Every year, we hear the Siete Palabras in English. We have become used to it since we don’t have any other choice. We need to learn to communicate in English.

Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.

My Papa went inside the house, babbling. He had only caught a small amount of fish, and his small rusty fish bucket was only half-full. “What else can we prepare? We only have bihon and your special lumpia tawgi.”

He threw his straw hat on the floor, but it made no sound. His curse followed, almost deafening. Mama said nothing in response, she just continued combing my hair, but her hands were shaking. “Just don’t leave yet, Inday,” Mama Amor requested, almost pleading. I could sense her anxiety creeping into my scalp. I knew Mama Amor. She was always frightened whenever Papa raised his voice or tried to hit her. She carefully chose her words when she talked to Papa, especially when he came home drunk. While Mama Amor fed him with attention and care, Papa fed her with: “You’re just my wife! You stay here in the house! You belong here! As your husband, do as I say!” Then, after a day, moons in various phases and sizes would appear on her skin.

“Inday, give me the real score.” Papa snapped, and gave a crusty you-better- answer-my-questions-properly look. And then, lit his hand-rolled lomboy cigarette. Outside, my brothers played hopscotch and bato lata, laughing.

“Huh? What is it, Pa?”

“You would be chosen by the foreigner, right?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t like seeing snow?”

“No.”

He was startled. Perhaps he recalled that we had a neighbor who wanted to be chosen by the foreigner merely because of snow, she said she would store it inside a jar and release it on the island whenever she returns home.

“There are lots of food to choose from beyond Dilaya, Inday.”

“There are also lots of food here,” I glumly replied, as I remembered the usual food on our plate.

“You can eat hamburrdyir and prens prays there. And pitsa pay!”

“We have puto and sikwate here, Pa,” I exclaimed. “I like them!”

Mama Amor stopped brushing my hair and secretly pinched me on my side. I gave her a look. A Ma-your-silence-must-end look.

“You’ll get a whiter skin if you live abroad,” father continued. Now in a grating tone. I know he’s drunk, and I can smell the pungent odor of lansiao, and alcohol from where I sat. “Your skin would look like that of an actor!” I saw the annoyance on my Papa’s face.

“You should like it since all men would whistle to catch your attention since you would have flawless skin.” He forced his laugh.

“I like my skin, Pa,” I shot back. “It’s brown, just like yours. I like our skin. And I don’t want to hear men whistling at me.”

Papa stopped. Anger illuminated his brown eyes. I heard the gritting of his teeth which I can only hear every time he falls asleep. “Talk to your daughter. Pisting yawa.”

Mother, here is your child; child,

here is your mother.

Mama Amor said nothing when Papa left the house. I think he chose to be by the seaside with his close friends. Like Papa, the majority of fathers on our island were bald and had lost their front teeth. They would often gather beneath the towering coconut tree, sitting on a bamboo bench, indulging in their nightly ritual of consuming tuba or rum without fail. In the moonlight, their bald heads would glisten, casting a shining glow. They will stay by the shore until dawn, sharing stories about how they treat and position their wives while making love in bed, all while ensuring that no one would leave the island without consent. Over the years, they have tirelessly labored to safeguard Dilaya’s dark secrets, fueled by gallons of tuba, stories, and more stories.

They also wouldn’t miss the opportunity to have fun at the expense of women. They joked about various things, from a nun who gargled holy water because her mouth sinned, to a woman whose panty was peeked through, and even a magical cliff where, if one jumps off, they would become a superhero, as they shouted. There was even a woman who tripped and exclaimed, ‘Ay, bilat!’ And so the joke went that she turned into a bilat herself, with the men bursting into laughter, imagining a human-sized vagina with a red cape.

Mama continued combing my hair until I heard her soft weeping.

“I cried because of the Siete Palabras,” she said while she sneezed on the Good Morning towel on her shoulder.

“Ma…” Her Mother’s wailing got louder. “What’s going on?”

“I’m starting to miss you, Inday.” Outside, my brothers played hopscotch and bato lata, laughing.

“We’re going to be alright,” I said.

I gingerly moved towards Mama, and gently leaned my head on Mama Amor’s shoulder; Mama Amor leaned on the words I uttered.

It is finished.

The snoring of my parents synchronized with the sounds of the cicadas. From there, I noiselessly crept outside our house to meet the girls by the shore. It would be difficult for us to get outside our homes if we would still meet on Black Saturday. No torch was lit. The surroundings were dark. My unfailing trust in them was the only thing I was holding onto in this darkness.

“Edna,” I called when I reached the shore. “Where are you?”

I see nothing. No light from the Moon. “Hey, we’re right here.” From disembodied voice. “We thought that you won’t be coming.” It was Edna. Then there was a light taken out from her bag. There were countless fireflies which were flitting inside the bottle. We are all complete: Edna, Joanna, Martha, and me.

“Hopefully, nobody will dilly-dally among us,” Martha gravely said. She stared at me. “I cannot assure you as to where we are going, as to what shore we are going to dock, if we would reach the city or get lost…”

“We will not get lost,” everybody whispered. “We will not get lost,” I softly said.

During the remaining hours of the night, Edna told us about a gathering of most of the boys, aged fifteen and sixteen, that had been happening for several weeks. She had heard that some boys expressed gratitude for not being taken by the red banca, and grieved over eventually losing their crushes and lovers. Their gatherings highlighted the difference between women and men. If girls gathered at night, it would be viewed with suspicion and doubt. Adults would have questions like landmines: Where were you? Who were you with? Why did you go with (so-and-so)? What did you two talk about? Did you know that he is the daughter/son of (so-and-so)? Each step is critical, as these questions could explode. That’s why girls on the island learned how to tread carefully, giving gentle, tiptoe-like answers to stay on safe ground.

I knew how serious our gathering was. I could see it in Martha’s eyes. “If we can get off this island,” she said, then looked at me. “We will ask for help. We will bring help here.” She paused and sat on a big rock before continuing, “Nanay said that there are government agencies that will help young girls like us. I don’t know what that agency is or what that government is, but that’s what my mother keeps telling me.”

“That is true, Mar,” said Joanna. “That’s what Nay Lisa told me. Especially when my Papa is not at home. Nanay tells me things about the city, and if I can go there, I shall ask for help from the government.” She paused, then said, “What is a government?”

“I don’t know, and perhaps, they are just another myth that we have grown up with,” Edna replied. And Edna approached me. “Don’t forget to paddle towards the mangroves. We’ll receive help there before the sun rises.”

What? I will paddle my way to the mangroves? What? I didn’t understand what she was telling me.

“Just do it…towards the mangroves. The mangrove trees on our island are dense, we…we have a lot of places to hide there. And one more thing, there will be someone who will meet us. Nanay told me that there would be someone who would be waiting for us who would fetch and meet us there.”

I just agreed, and we followed Joanna until we reached the big rock where our banca was hidden behind it. It was small, but Edna assured us that it would be enough for the four of us. Its color was unrecognizable due to the bleak darkness, and I could only see the stern. But Edna assured us that they could accommodate us in our exodus. The four paddles were also ready, according to her. Edna even confidently bragged that the banca had enough packed pieces of pan de sal, canned sardines, clean water, menstrual pads, and other necessities that we might need while sailing and once we were in the city.

“We are ready,” Joanna said loudly. “We’re ready to tell them our stories.” Then the three of them looked at me, and we all stared at the mangroves not far from our island. Someone would be waiting for us there. Someone who would listen to our stories.

I startled. “Where are you going?” Mama said, as she saw me on my way out of the house, carrying a plastic bag where I kept a few clothes. I just stared at her. I gulped. They must have awakened early. Are they too excited?

I forgot that Kapitan announced that the red banca would arrive earlier than usual, so everyone was forced to wake up early and prepare things before they could step on our shores. Kap even confidently assured us that a lot would be chosen. “Where are you going, Inday?” Mama Amor asked me again. Her tone was pointed. She stopped removing the scales of the fish.

“Ah! Outside, Ma Amor. I-I’m going outside.” I gulped, my heart already beating my throat. I repeated, “I’m going outside.” I could feel the sweat forming on my forehead as I repeated once more, “I’ll go outside first, Ma.”

“Where are you really going? What are you bringing inside that plastic bag?” I have to go out. I am throwing this trash. I raised the plastic bag.

My hand was shaking. Come on, act relaxed! “We-we’d be ashamed of our visitors with this, Ma.”

“I’d take care of that,” Mama said, as she wiped the fish blood with a rag. “Give me that.”

She snatched the plastic bag I was holding.

“Ma, I’ll be the one to throw that, please. Ma! Wait.”

I attempted getting back the plastic bag, but Mama had already thrown it outside, where Papa was plucking the dead native chickens’ feathers. “What’s going on there?” he said.

“Get inside the toilet and take a bath there,” Mama commanded, her voice already making me worried. “Inday, get inside the toilet!”

Tears fell as I was certain that Edna and the others were already waiting for me. The feelings of anxiety, helplessness, and fear gradually thickened and lingered inside me, ruthless like large waves threatening to swallow my paper boat.

As I went out, I forced myself not to cry. If they’d ask what’s wrong with my eyes, I could easily blame the laundry soap. I am pretty sure that Mama Amor and Papa already doubted me. I am certain that Mama Amor already knew the contents of the plastic bag. She’s always suspicious about everything I do. For Mama Amor, everything I do meant something else. For her, it’s either an act of rebellion or I was not being “lady” enough.

“What are these?” Papa’s voice boomed like thunder. The paper boat within me was gradually swallowed by his unforgiving sea. All the pent-up feelings inside me spilled out as Papa poured my clothes from the plastic bag, and coins followed, tinkling on the bamboo floor. “Tell me what these are!” The paper boat was now lost, now unfound. I felt myself starting to disappear.

“What is this, Inday?!” my Papa asked again, his eyes have storms continuously drowning me. “You want to escape? Are you crazy?!”

“DON’T COME NEAR ME!” I began to tremble uncontrollably. Mama Amor was shocked. But, there was already a need for a loud clear voice to be heard.

“The red banca will arrive, Inday,” said Mama. “And their coming is also the arrival of a rare opportunity to make our lives better! We would never suffer on this island anymore.”

I bent down. I have to do this. Then, I took quick steps, and swiftly jumped out of the opened window. “Come back here!” I can hear Papa shout.

“Release me!” he added. There, I saw Mama Amor trying to stop him.

I continued running, my bare feet pounding against the ground. I saw oozing blood mixed with dirt on my knees and elbows from the fall. My heart pounded loudly in my chest, matching the noise of the red banca’s grating engine. They’re here! I pushed myself up the steep incline of the hill, my muscles burning with exertion. Finally, I saw again the large red banca cutting through the waves, almost docking on the distant shore. We had to escape. Run! Every step on the ground stung, but I didn’t dare look back. I had to keep running. I was getting closer to the shore, the sun starting to rise in the sky. Wait for me! Edna! Don’t look back. Martha! Joanna! I called out their names, my voice desperate, urging them to wait for me as I raced towards the boat, driven by the adrenaline of the moment.

When I reached the shore, I saw the banca’s stern peering behind the large rock that was still there without the others. I was looking at my surroundings, but they weren’t around. What’s going on? Where are they? “EDNA, WHERE ARE YOU?”

Suddenly, I heard something on a nearby hill – a squeal. A tight tone that immediately caught my attention as I internalized the image of despair: The three of them tightly gripped by their fathers. “LEAVE US!” Edna exclaimed. “GO AND TELL OUR STORIES!”

No words passed through my throat. Tell our stories, in my mind. “INDAY, RUN!” Mama Amor screamed.

Rage was on Papa’s face as he struggled to descend from the hilltop, but Mama Amor was still holding on to him, her hands gripping the front of his shirt.

She lost her grip on Papa’s shirt. I found our banca behind the rock. “GO NOW! LEAVE!”

It was a small red banca. I pushed the small banca away from the shore until it was afloat. Someone will meet me there.

I looked back for the last time. I saw Lola Tasing. She was waving, as if spelling out ‘see you soon’ in the air. I won’t be lost, Lola.

The red banca. It wasn’t swallowed by harsh waves. This was not a paper boat. As my feet dug into the muddy bottom bearing the mixture of white sand and silt from the eroded soil from the mountain, my skirt and shirt soon wet with waist-high tidewaters, I resisted becoming a dead weight, I resisted getting claimed entirely by the sea; instead, my body, like my mind, floated. As the hazy bronze morning sky faded, all the more the surroundings even brightened, so suffused with light. The sea breeze tenderly and lovingly combed every strand of my curly hair–dancing freely in the air. The blue sky and the dense mangrove trees became clearer. I continued paddling in a frenzy. “Don’t get lost,” I repeated multiple times in my mind while paddling the red banca, quietly yet quickly and steadily leaving the island.