Meet me on Morayta

before we march to our beloved stronghold,

the Peace Arch in Mendiola,

where the blood of our martyrs

cleansed its cornerstone.

Swear that we will outnumber

the uniformed men in line.

Meet me there, but watch your back

lest a stranger follows

with sinister eyes.

“Don’t forget to pass by Mendiola

and pray at St. Jude’s chapel,”

Mother will say before my board exams.

Let’s greet Bonifacio in Lawton.

Turn to where he points his bolo,

to where we must go.

Across him is the walled city

where the summer flametrees bloom.

Do you wonder if he’s proud of us?

If this is what we must do

in his name?

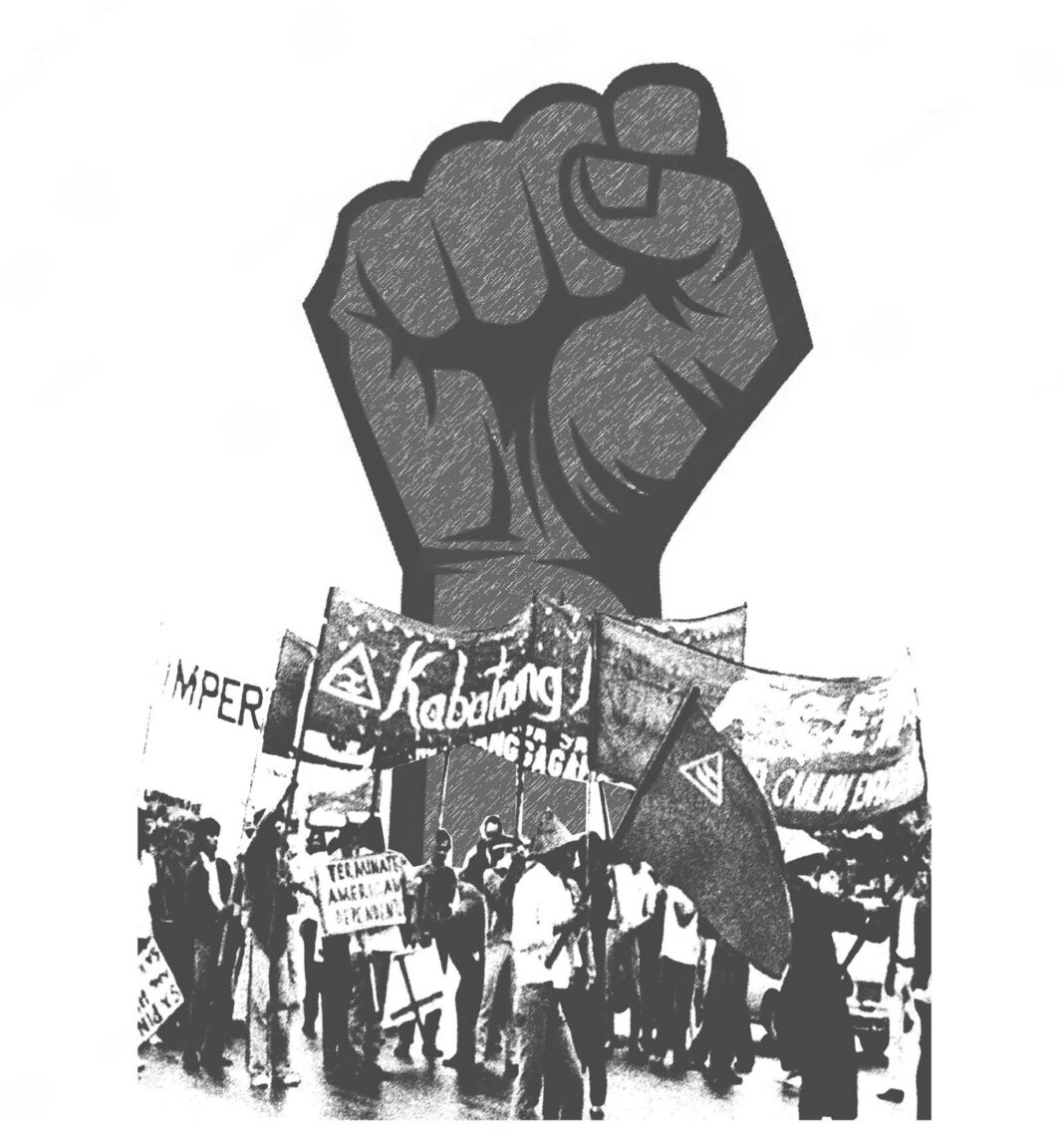

We sing of a new revolution,

the sequel to what he made.

“They built a fountain here?”

Father will observe, as Liwasang Bonifacio

becomes a gentrified mess to me.

See where the museum in Ermita stands,

the Old Legislative Building,

where somebody threw a coffin

at the dictator entering his car.

We don’t do it like that anymore.

We used to be more creative.

But because his children are still alive,

we may be lucky to try again.

So many of us have already died

for museums to remember our names.

“He really held his inauguration here, no?”

I will scoff, sick in the stomach at how the dictator’s son

wishes to erase the spark of the First Quarter Storm.

Chant with me on Jones Bridge

about the people, the nation,

now fighting back.

Wear red, black,

your comfiest shoes,

and be prepared to run

when the stoplights switch soon.

Never mind the odors of Pasig,

just scream and clap louder.

Our lives depend on it.

“They captured — butchered — him,”

one of us will say one day.

When the circle becomes smaller and smaller.

I will wait in Santa Mesa

where I offered my humble house,

so we can discuss the manifesto

in hushed but confident tones.

Family is away for the weekend

to give way for our chosen family

of political misfits.

As you pass through the gates

relax those weary shoulders,

unclench your fist.

“What’s in this box?” my sister will ask

of the contraband books and pamphlets

as we renovate the house.

Come quickly to Carriedo station,

so we can race to the dispersion

gone violent and add our bodies

to the barricade.

Bring nothing but a phone

that through captured videos

the rest of the world will know.

Put medics on speed-dial.

These pigs we do not trust.

They serve and protect none but themselves.

“It’s good that they didn’t make you go

up the mountains,” my older cousin will say.

He’s a policeman assigned in Karingal.

Hold these placards with me on España,

as we see our comrades goodbye

and hail their northbound buses.

Mother has left me ten missed calls herself

while we were locking arms

for the great motherland.

I have memorized this city

in such a short while,

but my own mother’s fears

I cannot.

“You don’t fight anymore?” a ninang will ask.

My Mom will smile and snicker:

“Your inaanak was just in a phase.”

Meet me on Morayta

in one of the cafes there.

Hear me cry about my choice

to “lie low,” to leave.

Judge me for still wanting

these petit-bourgeoise dreams.

Speak to me how we’re still human

despite bearing the nation’s yoke.

Tell me the movement will go on

without this sad girl’s voice.

“Are you willing to commit 42 hours a week

including Saturdays?” my employer will plead.

And I will nod. Blankly.