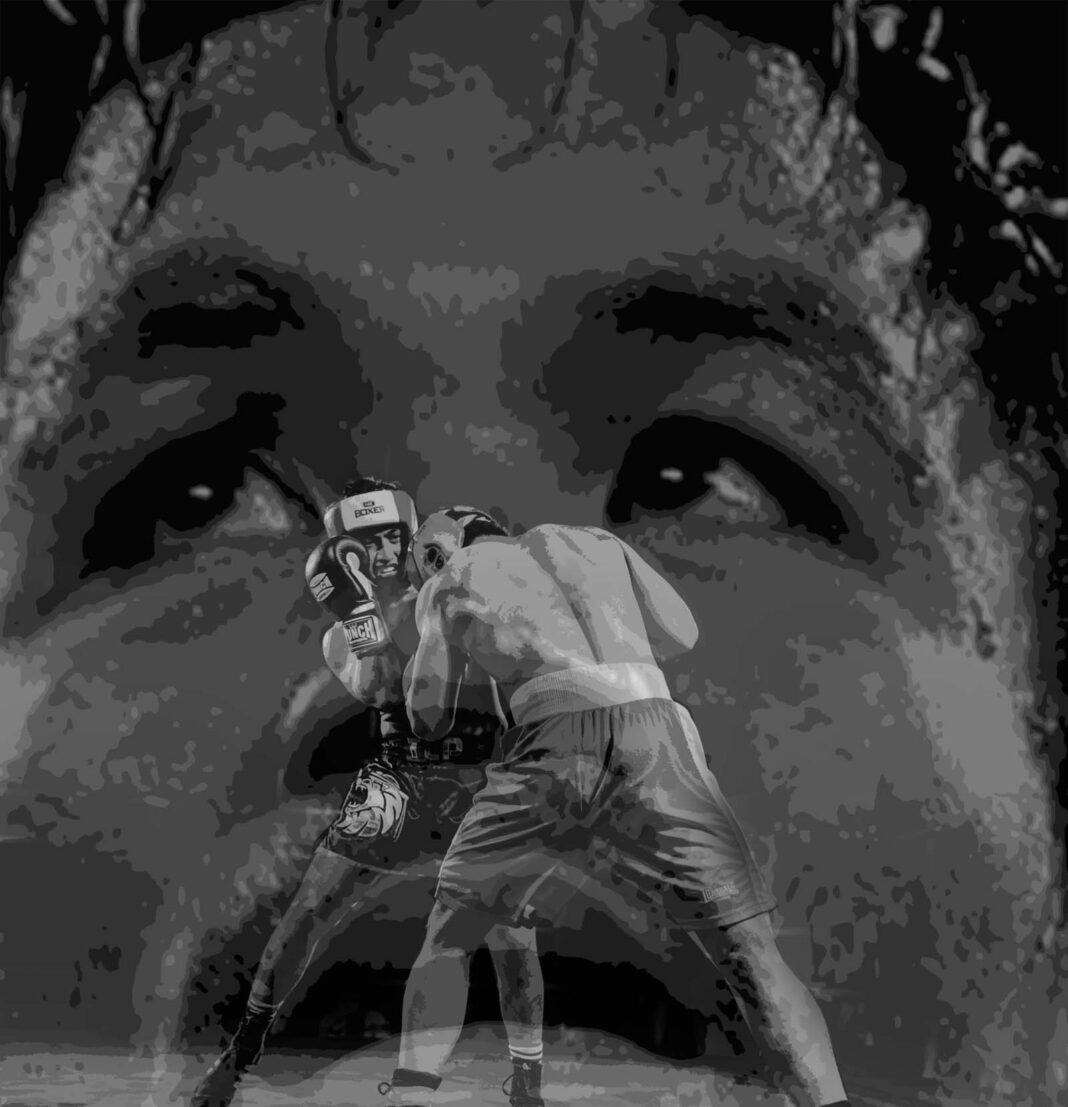

The buzz of anticipation is absolutely deafening. Boxing fans have jampacked themselves into the Araneta Coliseum to witness Felix “The Tornado” Abas, currently the WBC Bantamweight, division champion, and Joe Fairchild, the former champion, touch gloves for the second time. The first was a draw which Joe Fairchild loudly objected to, that is why The Tornado nodded to a rematch to end Fairchild’s sniping and to finally shut his mouth up. Based on the Coliseum gate, receipts alone, the wild and barbed nigglings have generated enough promotional buzz and reportage for the comeback bout.

To Eddie Valte, tonight is a special night for him. He is going for the big time, his first title fight and the chance to clinch a championship belt. He gives himself a little, nervous laugh as he tells himself: This is it. Eddie kisses the red gloves he wears for good luck. It has been a long stretch from the bottom, the days of barangay fiesta boxing fights. He is now on his first step toward the top and the top looks reachable. Eddie knows after this fight the view would be quite different. From now on. Starting tonight. He has made bettering himself in boxing his entire life. Winning small fights with small purses; everything he did was for one end. Tonight he is the man in a hurry to get there. Tonight, he is the new, future man of Philippine boxing, ready to confirm his place in sports history.

Eddie Valte was born in the poorer section of Dagupan City, in the province of Pangasinan, a place more famous for its bangus and shrimp paste than for anything else. Truth is, even after several months of training at the EZI Boxing Gym in Sampaloc, Manila, it still makes him feel discomfited to leave the confines of the gym and try the city streets on his own. Eddie was just a country boy who never got himself acquainted with the better things in life. At an early age, he knew he should not ask for anything from his mother, realizing how hard she tried to get both ends together, because he would not get it, anyway.

At school he resisted authority, but he excelled at fisticuffs. The wins over school bullies gave him his initial scents of victory and thus reassured him that he could go places with his fists and knuckles. In high school he was a delinquent and would have dropped out in his junior year hadn’t his mother, a tough but compassionate woman who can kick ass when it came to her three children, said she felt it in her guts that Eddie, her youngest child, would be the one most likely to have a better life. Eddie had always believed in his mother; he was, in like manner, afraid of her cold, menacing stare which she used to stop any brewing argument. She hated verbal ping-pongs, and Eddie had no doubt about that. His mother was also intensely Catholic and despite Eddie’s fondness for youthful fights, her religiosity made a remarkable impact on him throughout his adolescent years.

Eddie was sixteen when he got aware of the name Manny “Pacman” Pacquiao. It was on a big screen set up by the barangay people on a covered basketball court. The bout was at the Araneta Coliseum, against an Asian boxer. Eddie could not recall if he was Thai or Japanese. The bout was a big crowd puller and the Pacman quite easily lived up to the pre-fight hype. The contrast in skill was evident during the second round. Manny Pacquiao was clearly the aggressor. In no time he began to inflict glaring welts into the Oriental champion’s face. Every punch connected—the hooks, the jabs, the quick lefts, the uppercuts and before the bell rang to end the fifth round, the poor man melded with the canvas. Manny’s impressive win caught Eddie’s eyes and heart and since then Pacman had become his idol.

Eddie saw Manny Pacquiao in himself—short, lean, brown muscular arms, strong legs, light in body frame, poor and anonymous when he started to fight, has a strong-willed and very determined mother, an absentee father, appreciated a lot of attention the way the boxing fans are fixated on Manny’s every move in and out of the ring. Eddie would be as famous as Manny, ornamenting most major TV shows, but most of all, Eddie wanted to please his mother. Give her all the things that would make her happy—a cellphone, a car, big-screen TV, a big house with a big swimming pool, a diamond-studded bracelet, shoes and bags, signature clothes—everything she didn’t have and could only dream of because the family was poor and needed to survive.

Eddie Valte’s mother did not pin any medal on him but she was ecstatic enough that her youngest child finished high school and could read all the newspapers and magazines faster than his brothers with more comprehension. She was sure Eddie could get a job, courtesy of their barangay captain, except that Eddie had already decided he would be a boxer, just like his idol Manny Pacquiao. He would not be a puny messenger or an unappreciated errand boy of some barangay captain. Eddie had a reason to believe that boxing will lift him out of the concrete piers and fish smell of Dagupan, turn himself into a hero, a myth just like Manny. And what was to stop him from a Manny Pacquiao magnitude boxing superstar? He could not think of a thing that will.

HER FACE TWITCHED INTO A grimace when Eddie told his mother he would be a boxer. “Enough of that boxing talk, Eddie. One more boxer in the family is too much for me,” she told him, shaking her head, her mouth bristling on empty upper gum.

“Why can’t I be another boxer?” Eddie asked. “Father was a boxer, and a champion at that.”

“You’re right, your father was a champion boxer. Look what happened to him, what boxing did to us.”

As a boxer, Flash Valte had a thundering rise but the victories didn’t stick for as long as he had wanted. He made a lot of money relative to his fame but he was a show-off and was great at it. It was one bimbo girlfriend after another, and Eddie’s mother found herself having her fill of her husband’s rambling infidelities. Good times, besides, there were other things to take care of: his handlers, the coach, hangers-on, a corrupt accountant, the BIR, and the press. In other words, Flash Valte opened his champagne bottle too over eagerly and too soon.

The house he had built for his family was gone, too. His wife stopped asking for money—the vexing old songs, he would call her requests for money, and as a result ,the relationship hit rock bottom as quarrels became the daily sight at home.

Coming from church one Sunday morning, when Eddie was twelve years old, a police car, its roof light gently rotating, parked in front of the small house where they moved in after the bank foreclosed the big house they owned. It was obvious from the way Flash Valte was done in that his death did not come swiftly. His hands were mutilated, the fingers so unmercifully smashed that the bones blended with the flesh forming a gruesome mush. While the torture might have taken a long while, a single shot aimed at the temple was the “coup de grace. The family was told the gambling syndicate operated that way and the police had no doubt Flash Valte’s gambling debt, gone unpaid too long was collected irrevocably in that manner.

“You don’t realize how much I anguished over your father’s death,” his mother said, flinching at the memory.

“I’m doing it for you, Mother. I’ll take care of you the way Father did not. I can be famous and still be a good son,” Eddie said, his eyes leaking tears.

Eddie knew his father did not take care of the family and that knowledge had somehow shrunk his father in his eyes. His father—famous, tough, recklessly generous to his friends—was promptly forgotten at death.

“Forget about boxing, Eddie. Boxing is not for you,” his mother said and raised her arms with finality.

“I’ll prove it to you,” he said and turned his back.

“Eddieee!” she caterwauled but he decided to ignore her.

She sighed, shaking her head grimly. What mother does not feel pain on learning of the injury of a child she could not minister to? Boxing is a cruel and dirty sport—she knew it first hand.

One early morning before the cock’s crow, Eddie slipped out of the house and boarded a Victory Liner bus bound for Manila.

LOPE REALO SPARRED WITH FLASH Valte years before the ex-champion hit rock bottom. He had married Flash Valte’s cousin and decided to move to Dagupan to venture on the bangus fish pen business. Realo had felt that he didn’t have enough fire in his belly to continue, having absorbed some considerable pummelings on the ring. But he also knew that the boxing rings were spellbinding attractions to young men obsessed with escaping dirt-eating poverty and fire-trap squatter dwellings. When Eddie approached him one week ago at the fish port, Lope Realo could only sympathize with him. The kid had clearly an eye for glory.

Lope Realo took him to EZI Gym where he used to train. He had maintained close friendship with the owner who had trusted him with scouting around for apprentices.

To earn some spending money, Eddie Valte did janitorial job at the gym. Two weeks into his job, with a little cash in his wallet, he decided to send all of it to his mother in Dagupan. He hoped that she would spend a greater portion of it in buying rice. Dagupan always got knee-high deep in flood waters each stormy season. People who took shelter in claustrophobic, suffocatingly humid evacuation centers would grow restless and worried themselves to death, wondering how to get by. Many years ago Eddie, his two brothers, and his mother, were in a similar situation. People from a television channel distributed relief goods and sacks of rice. A delirious crowd, infuriated with a seemingly inefficient system of doling out, went unruly and started to fight over the rice sacks. Much of the scuffles were caught on TV, the sort of human fragility a television network loves to pick up.

FOR SIX MONTHS EDDIE VALTE toiled hard for his dream—going through the humdrum of janitorial work and sending his money to his mother whose silence kept dogging him throughout. But when he was on training, he sparkled and not once, in spite of the rigidity, the rivulets of sweat, the aching muscles, and longings for home, did he think of giving up. Lope Realo knew how Eddie ached to make that splash on the ring; he kept his patience as Eddie nagged him no end for a chance. The green light came one night while Eddie watched a rerun of an old Manny Pacquiao fight inside the gym owner’s office. It was a historic moment for Eddie, the definitive moment he had hoped for in his life. He whooped and shrieked, high-fived everyone in sight. It was like, all of a sudden, he would be inside a real, honest-to-goodness boxing ring, spotlights and all that!

His worst fear was riding on an airplane. He had always been frightened by the idea of coming apart, limb by limb and whatever else, high up in the air should the plane crash. But Eddie was bent on becoming a boxer, like his idol Manny Pacquiao, so he acquiesced to Lope Realo’s urgings to fight in Cebu. He had cautiously warned Eddie that boxing is not an easy job; that all accompanying risks, including an airplane crash, must be embraced with an open heart. Lope told Eddie, “You know, however ecstatic you might be when your dentist postpones an appointment, your joy is only short-lived. Sooner or later, you have to sit on that dental chair and get it over with.”

The night before the following morning when they boarded the plane for Cebu, Eddie wet his bed.

HE FOUGHT ALMOST ERROR-FREE—every attack according to Lope Realo’s strategy — his hands a perplexing blur. His opponent, his face splotched with blood, seemed bent on survival. Eddie kept pounding on and within minutes of the third round, he knew he was destined for greatness. The Cebu Coliseum roared its approval as sports reporters rushed to create a moss pit around him. It was finally tangible and real. He was a winner.

Eddie excused himself and hugged Lope Realo sweetly, the way a father would be embraced by a grateful son. He was giddy, felt the absolute feel of victory as he whizzed his way toward the locker room, like a jubilant gradeschooler on the last day of school. Lope Realo looked at Eddie with a father’s eyes.

It didn’t take long for Lope Realo to convince sports writers to spend some ink on Eddie’s first professional win. He made sure Eddie palled with celebrities and had revering spreads on the sports pages of leading newspapers.

FIGHT AFTER FIGHT, EDDIE AMAZED Lope Realo. Each punch landed on target—the jabs, the left hooks, the incisive rights—always looking for knockouts, a vulture circling for the kill. Through all his victories, Eddie thought of Flash Valte, his father. No, he would not fade away as cold-bloodedly transient as his father did. He would quit while at the top of his

game, fend off any wrecks from more fights so that he won’t be like Rolando Navarette—physically deteriorated, impoverished, and a totally ignored man.

HEAVILY PROMOTED AS THE LEADING fighter of the year, sports pages predicted Scott “The Puma” Wilson as the one most likely to go all the rounds for a lightweight championship belt.

Tonight at the Araneta Coliseum, Eddie approached the fight with an overwhelming fore destiny.

The bell rang a few times. The referee summoned both fighters to the center of the ring and reminded them of the rules. As the two fighters circled, Eddie suddenly jumped in with a left uppercut that straightened Scott Wilson out of his crouch. Eddie was in a savage mood, fueled by an excruciating pressure to be something notable. One after another, Eddie’s punches came and landed, violent, rib-cracking cannonades, each one a sulfurous menace. Scott Wilson was moving left and right and did not show any sign of weariness. Eddie had fired his best punch, what he called his Manny Pacquiao punch, but The Puma did not go down. He thought he was just as fast as Scott Wilson, then the Puma threw a methodical right punch that hit Eddie smack on the left eye.

The pain was very real. Eddie shook. He saw stars spinning behind the eyelid. The referee was a blur through Eddie’s impaired vision.

The bell rang to end the eleventh round. Eddie felt a draining fatalism. He knew the only way he could get at Scott Wilson was to land that lucky punch, and it wasn’t coming.

At the end of the twelfth round, as Eddie sat in his corner catching his breath, Lope Realo rubbed the blood out of Eddie’s left eye with a towel. He didn’t say much. A ring doctor went up to Eddie’s corner and studied the swollen eye.

He said gloomily, “You got the belt all right, but your games are over. This mess is a twelve-stitch cut.”

EDDIE HURRIED UP TOWARD THE locker room with Lope Realo right behind him, fending off the horde of reporters and photographers. He carefully laid the championship belt inside a black duffel bag. Suddenly, decidedly, boxing was over.

Eddie zigzagged his way past the press people outside the locker room, not looking back. He could sense that people were looking at him, the champion. He felt uneasy and doubled his steps.

He thought about his mother. She would rejoice to know that her son is giving up boxing. The fall from grace was true. Boxing was a magical world, yet fang-baring and cruel.

The world outside the boxing arena beckoned. His mother would be glad to see him.