Cicadas talk to each other in loud, prolonged streaks of staccato bursts. For a few minutes before sunset, the insects make sound and give it an almost palpable feel. The upswell of choruses stir the air, and dusk’s fractal lights of brilliant orange pierce through the madre de cacao to form patterns on the ground where the dust motes dance in a hypnotic sway.

Ben loved their song. But not today. He slumped on a dusty pile of kindling beside the screen door and leaned against the crude hollow blocks held together by uneven glops of cement. This went all the way up to the base of the windows. Bamboo slats bordered the naked sheets of plywood walls. Several splotches of watermarks stained it into a deeper brown, the gaps in the nipa roof had allowed the rain to spray through. There were places where the constant rain had melted the plywood altogether and the gaps were covered by sheets of metal and several painted boards bearing various insecticide brands.

A healthy hedge of snake plants bordered the house, twisting out of the damp earth like tongues of flames from candles lit at the Nuestra Senora Candelaria Church at Jaro Plaza. Nana, his grandmother, toiled with hunched spine and uneven shoulders over the plants, and with a painful, waddling gait, watered them daily with a pail she filched from a nearby construction site.

From inside the house, he could hear Sir Indon’s thick guttural accent murder the delicate cadences of Hiligaynon. The loan shark, a dark, towering, pot-bellied man stooped to the level of his clientele, thus the change in name, and spoke their language as well. Nanapleaded softly as she was methodically scarfed of money.

The screen door wailed in a prolonged twang. Ben immediately stood out of the way.

“Next week, ha?” Sir Indon garbled and adjusted the turban on his head. “Next week.” He wiped away the rivulets of steaming sweat and swatted at the cloud of biting mosquitoes that roiled above him like a tornado. He roared off in a skeleton of a motorcycle, alarming a clutch of chicken brooding in the nearby bamboo cage.

Nana smiled and bobbed her wispy, graying hair, her twisted back brought her closer to the ground with each genuflection. Ben’s stomach tightened at seeing Nana’s face. Her eyes were half closed, the lips partly open in a beatific smile. The creases in her brows had unclenched, the furrows shallower. This was the face she put on for other people. It reminded Ben of the unpainted papier-mâché masks sold in Central Market, unnervingly smooth and neutral.

Nana had the same look five years ago, when they stood beside the hospital bed as doctors and nurses clambered over themselves in the crowded orthopedic ward amidst the rot and decay, as they unsuccessfully tried to revive his grandfather who was admitted for a broken hip. A blood clot from the fracture had travelled to his lungs, the doctor said. Nana smiled, saying it was all for the best, he had a good life. But it wasn’t, as she squeezed her dead husband’s hand and shook like a young datiles tree during the monsoon. She slowly crawled on top of her husband’s inert body and stifled sobs that wracked her frame. Ben didn’t know what to do. At 12 years old, he wasn’t supposed to be there. But he had no place to go, so he stayed rooted to the spot, watching his nuclear family fall apart.

Ben stood up and smoothened his bell-bottomed brown corduroys, the hem sopping up the mud, darkening the fabric. The orange polyester buttoned-up polo was the rage of the day, but it clung uncomfortably to every surface that sheened with sweat. A high, upright butterfly collar made it worse, tugging at the tiny strands of hair at the nape, while the tag insisted on dragging its teeth across his skin. These were his grandfather’s. He dusted his hand and ran it through his impertinent hair. The oily yellow-green pomade didn’t help. His body hadn’t made up its mind: the nose was too large, the mouth thin and huge brown eyes were frilled by abundant lashes. His dark skin was taut in most places, as if caught unaware that the rest of him was getting bigger, that Ben was molting into an adult. A stupendously late bloomer, he shot up several inches the past few months, his genes dictating he was to be a flagpole.

Nana quietly hummed beside him. They were supposed to go out to Kong Lee Restaurant for a rare treat to celebrate his high grades. That was until Sir Indon’s visit. He had a nose like the feral rats that hunted for fresh chicken liver at night.

“Ben, would you like to go see your Gran?” Nana said after some thought.

Ben nodded at length and helped his Nana across the sea of wet grass that fronted their house. He shoved the bamboo gate shut and secured it with a ring of hard wire that went over the poles. The drizzle finally stopped. But it was still a good 100 meter walk over muddy rice paddies until the sturdy wooden bridge which when crossed, led to the city highway. The transition was almost palpable. Most of the people across the river were farmers, and those on the opposite end earned their living in the city. The river which divided the farmlands of Barangay San Isidro from the high buildings and cement streets of Iloilo City gave the place its literal name: Tabuc Suba.

The Jaro CPU jeepney dropped Ben and Nana at the front of Doña Amalia’s estate, embroiling them in an oily black cloud that caused momentary blindness. Gothic pillars and sturdy tridents lined the property. Impossibly straight trees shot up towards the early evening sky. Heavy, wrought iron gates and thick bougainvillea hedges prevented eyes from peering in at the mansion. It was a modern-day fortress.

Nana pressed a doorbell and waited. A few minutes later, a woman dressed in black maid’s uniform appeared and let them in. Such affluence shocked Ben. An undulating copse of rosal, its heady fragrance diluting the early evening air, bordered the vast front lawn of manicured bermuda grass. Several mini greenhouses held tropical treasures: rare orchids in superfluous bloom, bromeliads in all sorts of vulgar colors, and even an aviary of lovebirds. The mansion itself was an enormous thing that seemed to hulk out of the ground. Swathes of forbidding gray marble stretched across its face while floor to ceiling windows looked like the translucent front teeth of a rat. Instead of statues and bas reliefs, intricate iron crosses stabbed at the sky like metal tendrils.

The maid led them through an incongruous, narrow foot walk towards a hidden niche beside the house, where a small water pump was located. Nana gratefully sank on a garden chair. Water sluiced from the pump and Ben vigorously soaped his own feet and Nana’s. They dried them on clean rags and entered the mansion through a side door reserved for the house help. The kitchen floor was cold to bare feet; Ben’s heart seized at how Nana’s rheumatism will cost her later. Her toes were twisted and gnarled, like luya fresh from the moist ground. Her thin legs had feet bent far apart. She walked like a rocking boat, and the pressure of her hand clutching his arm matched the rhythm. Ben smiled shyly at the cluster of cooks that bustled about, but their voices hushed and the room fell audibly silent. Ben could feel their eyes on him as they walked past.

The sprawling mansion was empty except for the help, who turned their faces away when they approached. The air was heavy with some peculiar Oriental scent. They followed the same maid to a modest anteroom and settled on the comfortable sofa. Through the door, Ben could see the expansive sala with blinding crystal chandeliers where the household entertained guests of importance. He remembered the single gas lamp that gasped fitfully and hard bamboo sofa they had at home, creaking at the joints, with the excrement of tiny wood-eating insects powdering the packed mud floor. He felt himself contracting, made smaller by the nauseating show of wealth.

Doña Amalia Fuentespina Salcedo was the scion of a shipping and business magnate who married a doctor—a surgeon. All wealthy and influential families of repute clustered about the city plaza, and her house was ensconced in an expansive property that boasted the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Jaro as its neighbor. Her daughter, Aurea, was Ben’s mother. Aurea had a heart condition, one that often amounted to palpitations and fainting spells. Naturally, this ensued to a cloistered existence marred by streaks of teen-aged rebellion. Aurea would periodically escape her one-hectare gilded cage.

Aurea met Antonio, Ben’s father, during a basketball match between the best private and public schools in Iloilo City. Upon seeing his merry grin, tousled hair and hard, lithe body, Aurea hatched a plan. She wooed him masterfully with a soft lilting voice and shy, downcast eyelashes that fluttered upward at his every word. When she was sure that he was adequately smitten, Aurea then flounced about the mansion with the infatuated farm boy tied neatly to her little finger. Oh, what delicious scandal! The highborn ladies vibrated with such meaty gossip. Aurea scarcely cared. She used him to unnerve and infuriate Doña Amalia, skillfully flinging him at her during the most inconvenient of times, especially when the local hoity toity visited. Antonio was too besotted to notice she used him to exact revenge. Aurea wanted her mother to squirm, and the distinct lack of refinement in the boy was perfect.

The relationship lasted for three years until Aurea became pregnant while studying at San Agustin. The resulting outrage was two pronged: not only because of the steep incline between their social classes but also because the pregnancy would be catastrophic to her heart. Aurea clung to the baby, though, and Ben was delivered without any consequence via caesarean section. It was a miracle, everyone gasped pleasantly, that her rheumatic heart did not worsen during the pregnancy. But they found her pulseless ten minutes after the last vital signs assessment, pale as chalk. Her unnaturally floppy uterus failed to contract post-operation and all the blood mutely gushed out. It was unfortunate that the recovery room stretcher had a slight dip to it and contained her like a bowl does to soup. Not one drop splattered on the aseptic hospital floor. Aurea died in her sleep, swimming in her own blood.

“Maayong aga, kumare, Ben.” Doña Amalia ceremoniously swept into the room. She was a haughty, gem-encrusted apostrophe; tiny and spherical, dressed in the latest terno, with an immaculately coiffed hairdo. Despite her small stature, she always managed to look down at them through her thin, beak-like nose. She circled a singular, gaudy throne of a chair, the focal point to where all the other plain furniture were directed. Nana and Ben stood up when she entered and only sat down after her.

Ben could feel Nana dissolving and shifting. She had her mask on: affable, smooth faced, self-deprecating. She managed to curtsey without standing up to bow. It was revolting how she pronated herself and wallowed in the mud on the immaculate marbled floor. Ben wanted to heave her up and leave.

“Doña,” Nana said with a slight bow, “your grandson has very high grades. Benjamin could be valedictorian.” she said, giggling. Her grin made the consonants more affable, the words whistled merrily through the toothless gaps.

“Natural! He is Aurea’s son, after all. My family is not stupid.” Doña Amalia frowned, as if the thought insulted her. “How much do you want, Dolores?” she said, cutting to the marrow.

“If you please, five hundred pesos, Ma’am. I must pay my dues to Sir Indon, and I promised Ben some Sun Yat Sen noodles to celebrate.”

“So, you will pay utang with another utang?” she laughed in a tinny, high-pitched choking sound and smiled the way dogs did, all teeth, no mirth.

“How about Benjamin’s tuition when he’s in college?” she swiveled her head and her eyes bored into Ben’s. “Ben, come stay here. Just bring your books.” He couldn’t answer back, his tongue curled up in the acid in his saliva.

“Antonio is due for a promotion, ma’am,” Nana’s lucid voice came in. “He will not be a laborer in Saudi forever. He is next in line as foreman. And Benjamin has already applied for several scholarships.” Ben mutely bobbed his head, eyes wide. He was not afraid of studying, slaving at his books until he could see the outline of tomorrow’s sun. There was a hint of manic desperation he had when studying. A small, shameful part of him knew the real reason why: he was deathly afraid to grow old in poverty. Staying poor was a death sentence. Education would be their way out.

“Do whatever you want.” Doña Amalia sighed in surrender, visibly souring at Antonio’s name.

She stood up, and with immaculate skirt whispering, went to where Ben sat. She hooked his chin up with a V she made with her second and middle finger and stared down at his face.

“Ah, there you are, Aurea. Right around the eyes.” Doña Amalia’s face softened and Ben glimpsed a forlorn loneliness before her features shuttered close. She straightened abruptly and without preamble, left the room.

Ben exhaled loudly and shook his hands to loosen his clenched fingers. Nana, visibly relieved, stood up and headed to the restroom.

The corridor which led to one of the numerous powder rooms felt like it belonged to a museum. Acrylic and watercolor paintings depicting idyllic farm life decorated the walls: spotless rivers teeming with fish, healthy, bathing children and gracious women doing the laundry, a lazy afternoon on a carabao’s back. Ben thought of the murderous cracks in the rice paddies after a long drought that could break your ankle if you stepped through it in the dead of night, and of the sharp, jutting hip bones of the random goat that munched on whatever foliage it could find.

The door to the restroom opened, and Ben helped Nana step out. “I will be fast, Nana. Don’t go without me.”

The restroom was larger than their own sala and kitchen together. There was no antiseptic smell; the scent of rosal from the garden filled the room. The sink was pristine, with dark blue edgings of birds and flowers reminiscent of Chinese porcelain. But it was the ornate brass faucets that fascinated Ben. Opening one or the other brought hot or cold water from the faucet. Turn both, and lukewarm water came out. And the soap! It produced such an expensive lather. This was the highlight of Ben’s visit to his Gran. Such casual luxury for something as conventional as the restroom. A sliver of envy and resentment stung him. This could have been his life. Ben immediately shrugged it off. He was content with Nana and even with Papa Antonio who had returned home only during his grandfather’s death.

The walk back to the narrow entrance of Tabuc Suba was quite pleasant. The clean air managed to warm and cool Ben’s face at the same time. Faint, rushing water murmured pleasantries in a far-away voice, as if children were playing among the rampant mats of kangkong. His heart was buoyant. Nana’s cloth purse which she firmly sandwiched between a hefty breast and a bra’s cup, was pregnant with five one hundred peso bills. He will get his scholarship. His Papa will be foreman. All will be well.

“One day,” Ben murmured to the river, “I will cross to the other side.” It cheerfully agreed.

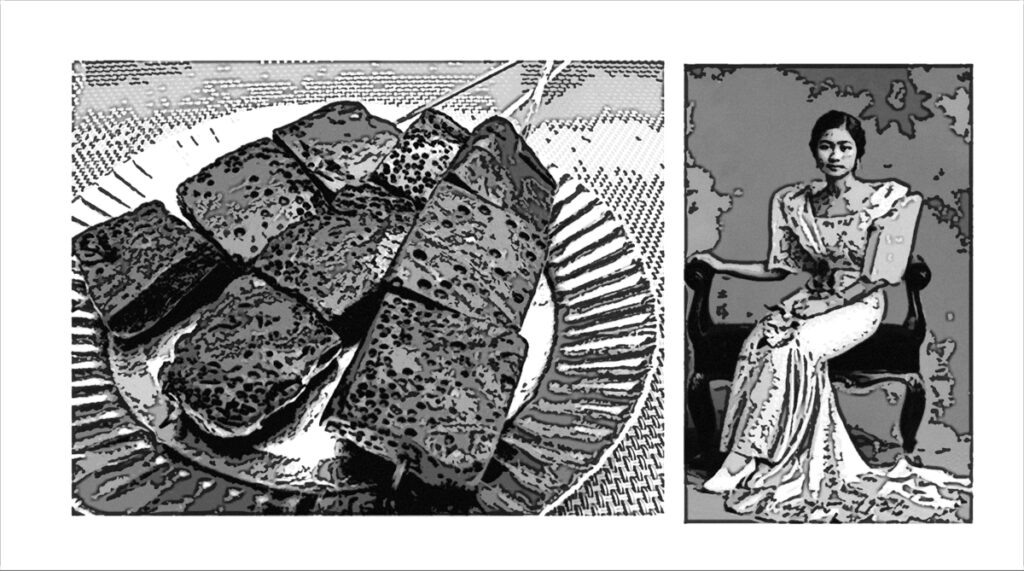

At the foot of the wooden bridge is Nanay Tina’s barbecue stand. As it was nighttime already, they decided on chicken inasal and isaw instead. Ben was partial to Betamax, coagulated pigs’ blood cut in rectangular cubes, barbecued to a crisp crust, and a crumbly, savory center.

Nanay Tina, rotund and jovial, was his Ninang. Alhough she was a full decade younger than Nana, they were fast friends. The nights they had inasal for dinner were the nights they had no money for food. Tonight, though, they could pay for chicken inasal, isaw and even Betamax. Ben’s mouth watered as he inhaled the smoky aroma of cooked meat, burnt sugar, and catsup.

“Uy, Nang Dolores! Valedictorian na si Ben?” Nanay Tina merrily seized Ben’s arm, and waved the abaniko she was using to burn the coals. “Before I forget, Antonio sent a telegram.”Nanay Tina handed Ben the unopened envelop after scrounging for it in her apron. She also wrapped the skewered morsels in a thin sheet of brown tracing paper and placed the contents in a plastic bag. Nana nodded and thanked her. The walk back home was faster this time, propelled by the thought of warm food and glad news.

Ben pumped the kerosene lamp with as much fervor as his complaining stomach goaded him. Nana placed the barbecue on a plate and set the wrappers aside. Rice steamed as large clumps of white bliss on each of their plates. This was heaven.

“Ben, can you open your Papa’s telegram?”

Ben carefully tore the side of the envelop. The telegram was a diaphanous piece of paper and he could make out the lamp on the opposite side. He lowered it and frowned at his grandmother. It did not make sense. He had to read it aloud, make it more real by hearing it from his mouth.

“AKSIDENTE MOTOR. BALI SIKO.

NO INSURANCE.”

It started to rain again; fat, angry droplets bombarded the naked nipa roof. Some managed to sneak through, splashing intently on the mud floor and on the unfeeling Ben. He was drowning in the vortex of a raging tornado, the tumultuous winds rushing at him. He could not breathe and the whistling noise in his ears made it hard for him to think. Each time he could poke his head out of the miasma, more would come pouring in, filling his mouth and nose to invade his lungs.

So much was happening at the same time. Thoughts about his father alone in Saudi, his elderly Nana, the debts—all roiled about him. He was blacking out. Ben abruptly stood up, rattled the table and toppled the lapad bottle of vinegar. A lengthening finger of sinamak slithered across the table. He turned to wipe it and the acrid vapor pierced his nostrils. He remembered with clarity: Gran’s soft, creamy soap, the rich suds and the gentle perfume. This contrasted sharply with the evil thing that rapidly blotted the dirty plastic table.

“Baho! Kabaho gid!” he shouted, forcefully dragging the damp rag across the table. He could not look at his Nana. Hot tears welled up but refused to flow. So, with cloudy eyes, he stood up, and staggered to his room. He knew what to do.

With a bag full of his books, he peered into the kitchen, arguing with himself as to what to do next. The lamp limned Nana’s figure, her face awash with the light, while some parts were anchored to the inky blackness. She was humming off key as she bustled about, slipped a bit on the rain water on the floor which had turned the mud into soft clay. He had forgotten about dinner. He saw her put more than half of her rice on his plate. Nana meticulously pulled out the tasty morsels from their skewers and piled them high on his. She tugged a small chunk of meat from the chicken, methodically shredded and added it to her rice. Nana then took the plastic bag and tracing paper, and slowly upended it on her plate, letting the leftover sauce rain down.

Lifting the brown wrapping paper, she tore it carefully into small and tiny pieces and put them on her plate. She took a dollop of rice, stained and made malleable by the sauce, made a crescent in her palm and buried the bits of paper, carefully adding enough to make the ball bigger. Her plate did not seem halved of its contents when she was done. This was her dinner. She picked up a string of isaw, thought about it and returned it to Ben’s plate.

“Come, Ben! Let’s eat!” she cajoled him as he entered the room. He sat down and placed his bag beside him. He knew she saw the bag and what that meant. He glanced at her and Nana was gazing back at him with lidded eyes, the lips parted in a beatific half smile. The creases on her brows had unclenched, the furrows shallower. She was relaxed, contented even. But he knew. There was a tranquil, defiant acceptance of his decision. Nana had let him go.

“Betamax pa, Ben?” Nana picked up the cube of cooked blood from her plate and set it on his own. He could hear her laboring at her rice ball, intentionally chewing and swallowing it.

“Thank you, Nana.” Ben struggled to eat. A terrifying loneliness seized him. Tears that had earlier been unshed are now freely salting the rice.

“Ben, you’ll let me visit, yes?” a timid voice beckoned him, and he felt bone-thin fingers touching his arm. Ben wiped his eyes dry, squinted them in imagined mirth, his lips turning up in the corners. The muscles of his face gradually smoothened. His mask was nearly complete. He was her grandson, after all.