“There she is,” the woman in the car told her son, as she pointed to a petite and thin sampaguita garland vendor sitting on the stone steps of Mercury Drug in Scout Borromeo, Quezon City.

Rising, the vendor’s pale, harried face dissolved into a warm smile as she approached with a sprightly step the woman and her son.

“Aling Juana, kanina ka pa ba [have you been there for long]?” the woman in the car asked.

“Kadarating ko lang [I just arrived],” she replied.

About 50 years old, Aling Juana had just walked some 500 meters from Tomas Morato, where she hawked sampaguita to passersby and bar habitues—from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., every day, in sunny or rainy weather—all the way to Mercury Drug in Scout Borromeo.

The security guard at the drugstore, a friendly chap, would let her sell her now almost wilted garlands to people who came around to buy medicine.

In the wee hours of the morning, events company owner Stephanie Sandiego and her son Kevin first met and befriended Aling Juana, shortly after a gig they handled in one of the bars along Tomas Morato.

Here, in front of Mercury Drug, where Stephanie was about to buy her medicine, Aling Juana cajoled her to buy sampaguita.

Taking pity on the woman, the owner of Actualizer Global Co. (AGC) Media Management bought the garlands. And there began a 15-year friendship, with Stephanie and Kevin always ready to give Aling Juana a hundred pesos, more than the P20 price for a bunch of sampaguita garlands that she peddled.

“Mahal namin si Aling Juana, nag-iisa lang siyang nagpapalaki ng kanyang anak. [We love, Aling Juana. She alone supports her son]. We try to help her, whenever we can,” she said.

Giving money and food to poor folk has been a project of love for AGC Media Management. Once every three months, the events company holds their Kaldero ng Diyos feeding program for children in depressed neighborhoods.

ADDRESSING POVERTY

The Philippines has an Anti-Mendicancy Law. Issued by the late Pres. Ferdinand Marcos on June 11, 1978, Presidential Decree 1563 states that mendicancy or the use of begging as a means of livelihood is illegal since it breeds crime, creates traffic hazards, endangers health, and exposes mendicants to indignities and degradation.

PD1563 states that people who engage in mendicancy will be punished by a fine not exceeding P500 or by imprisonment for a period not exceeding two years or both at the discretion of the court.

The Philippines has an agency dedicated to address poverty in the country. On June 30, 1998, during the administration of the late President Fidel V. Ramos, the National Anti-Poverty Commission (NAPC) was created through Republic Act 8425, known as the “Social Reform and Poverty Alleviation Act.”

NAPC coordinates poverty reduction programs by national and local government. Chaired by the President of the Philippines, NAPC is composed of the two Vice-Chairpersons—one for the government sector and another for the basic sector—representatives from 25 national government agencies, and representatives from 14 basic sectors.

Comprising the basic sectors are farmers and landless rural workers, artisanal fisherfolk, indigenous people and rural communities, workers from the formal/informal sectors and migrant workers, women, children, youth and students, senior citizens, persons with disabilities (PWDs), victims of disasters and calamities, NGOs, and cooperatives.

The country witnessed various anti-poverty programs and projects initiated by each elected President.

From 1992-1998, the late Pres. Fidel V. Ramos implemented the P9.6 billion Social Reform Agenda (SRA) as its flagship anti-poverty program, with the nation’s 20 poorest provinces as its priority beneficiaries.

For the Estrada Administration, the centerpiece anti-poverty program was the P2.5 billion “Lingap para sa Mahirap” (LINGAP) that built on the programs and projects of the NAPC, the Social Reform Council, and the local governments.

The Arroyo Administration introduced the Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) program in 2008, with a pilot of 6,000 households. Known as the Pantawid ng Pamilyang Pilipino Program or 4Ps, it gave a subsidy to poor families on condition that they keep their children in school, receive health care during and after pregnancy, agree to have their children immunized and monitored for growth with periodic checkups. Its overall aim is to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty.

The administration of the late Pres. Benigno Aquino III expanded in 2016 the 4Ps program of the Arroyo Administration to benefit a total of 4.4 million households on a budget of P62.6 billion. It introduced the K-12 enhanced basic education program and a Php50 billion housing fund for informal settler families (ISFs) living in identified danger areas in Metro Manila.

The Biyaya ng Pagbabago Tungo sa Masagana at Matiwasay na Buhay Pilipino” or Biyaya ng Pagbabago was the flagship anti-poverty program of the Duterte Administration. It is in line with the vision to reduce the poverty level from 21.6% to 14% by 2022. The Duterte government implemented the Rice Tariffication Law (RTL), the Tax Reform Acceleration and Inclusion Act (TRAIN) and funded with the help of sin taxes the Universal Health Care Program (UHC).

Under the administration of Pres. Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the anti-poverty efforts include the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), the DSWD’s Assistance to Individuals in Crisis Situation, the DOLE’s Tulong Panghanapbuhay sa ating Disadvantaged/Displaced Workers (TUPAD. The 2024 budget for the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino (4Ps) program is P106.335 billion. This is higher than the 2023 budget of P102.610 billion.

POVERTY LINGERS

According to a December 12-18, 2024 hunger survey of the Social Weather Stations (SWS), the number of Filipino households experiencing involuntary hunger has jumped to 25.9%, the highest since the COVID-19 pandemic.

About 25.9% of Filipino families experienced being hungry without food at least once in the three months before December of last year, the SWS said,

The survey data indicated that hunger in December 2024 was three points higher than the 22.9% hunger figure in September 2024. It is the highest recorded hunger since the 30% recorded in September 2020, during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

The 20.2% annual hunger average in 2024 was nearly double that of the 10.7% annual average in 2023. It is just 0.9% lower than the 21.1% record high hunger figure in 2020.

In 2022, the World Bank noted that the Philippines had one of the highest levels of inequality in the Asia-Pacific region. Around 1% accounted for 17% of the national income, while 50% shared 14% of the pie. The country’s Gini coefficient was 42.3%.

As defined by the World Bank, a Gini coefficient is a statistical measure of economic inequality in a population. The coefficient measures the dispersion of income or distribution of wealth among the members of a population. Simply put, at 42.3%, this means there is a large gap between the rich and the poor in Philippine society.

The SWS has been conducting quarterly surveys on hunger beginning 1998. Over the last 26 years (1998-2024), it has observed that “hunger has been volatile for decades; there is no long-term decline in the rates. The average rates of hunger are lower in 2021–23, compared with the pandemic year 2020, but they have been increasing since the last two quarters of 2023.”

The July 1998 hunger survey found that 15.3% of Filipino households in Mindanao experienced hunger, which was higher than the 11.3% in the Visayas and the single digit hunger in the National Capital Region (NCR) (6.1%) and Balance Luzon (areas outside of NCR but within Luzon, 5.1%).

In its December 2024 hunger survey, the SWS data showed that the experience of hunger was highest in Mindanao, with 30.3% of families experiencing hunger, followed by Balance Luzon (or Luzon outside Metro Manila) at 25.3%, the Visayas at 24.4%, and Metro Manila, at 22.2%.

PSA figures show that the Philippine population in 1998 was pegged at 76.5 million, increasing to 115.8 million in 2024. While the country’s population has not doubled over the last 26 years, its hunger figures have almost doubled in Mindanao, more than doubled in the Visayas, and more than tripled in the National Capital Region (NCR).

PRIVATE SECTOR & ANTI-POVERTY

Other than the government, the private sector has initiated its own programs and projects to address the problem of poverty and other ills afflicting the poor.

First described as charity or philanthropy in the form of donations to the poor made by rich families or individuals, the practice gradually evolved over the decades toward the formation of foundations and non-government organizations, eventually involving business corporations.

Among the first business corporations to establish civic-minded corporate foundations were the Ayala Foundation (1961), Ramon Aboitiz Foundation, Inc. (1966), Andres Soriano Foundation (1968), Eugenio Lopez Foundation (1968), San Miguel Foundation (1972), and the SM Foundation (1983).

In the paper, “CSR in the APEC region,” by the Asian Institute of Management RVR Center for Corporate Responsibility, it stated that “given the slow growth of the Philippine economy due to economic mismanagement and political instability, corporations saw it fit to be involved in social development, aware that businesses could not possibly thrive amidst an environment where the majority were poor.”

The paper explained that this more strategic approach “involved direct community engagement and programs that align social and business goals, with a growing emphasis on partnerships and addressing issues like poverty, education, and environmental sustainability, driven by increasing stakeholder expectations and the need to demonstrate a wider social impact beyond just profit-making.” This shift is often referred to as “Corporate Social Responsibility” (CSR).

BROADENING THE FRAMEWORK

The years 2008-2009 has been widely referred to as “The Great Recession.” Countries around the world experienced high unemployment rates brought on by significant economic contraction.

Starting in 2007, the global financial crisis continued to deeply affect the global economy in 2009. The economic downturn experienced by rich nations engulfed emerging markets and developing countries like the Philippines with reduced access to capital, falling demand for exports, and lower remittances from migrant workers.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its 2009 Global Monitoring Report: The global economic crisis, the most severe since the Great Depression, is rapidly turning into a human and development crisis. No region is immune. The poor countries are especially vulnerable, as they have the least cushion to withstand events. The crisis, coming on the heels of the food and fuel crises, poses serious threats to their hard-won gains in boosting economic growth and reducing poverty. It is pushing millions back into poverty and putting at risk the very survival of many. The prospect of reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015, already a cause for serious concern, now looks even more distant. A global crisis must be met with a global response.”

The IMF global call to action found resonance in a declaration of the United Nations issued two years before the IMF Global Report. At the start of the global economic crisis in 2007, the UN, during its 62nd session, proclaimed a World Day for Social Justice.

Wrote Thomas Hale in the UN’s flagship magazine, the UN Chronicle: “For the first time in its history, the United Nations is embracing business and civil society as vital partners in advancing its goals of international peace and development.”

Hale, a special Assistant to the Dean at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, added: “In today’s interdependent and globalizing world, business and the United Nations share common objectives. Despite different purposes—the United Nations works for peace, poverty reduction and human rights protection, while business has traditionally focused on profit and growth—the overlapping objectives of the United Nations and business are clear: building markets, good governance, combating corruption, safeguarding the environment, achieving global health and ensuring social inclusion.”

From this vantage point comes the concept of Corporate Social Justice. According to the Harvard Business Review: “Corporate Social Justice is a framework regulated by the trust between a company and its employees, customers, shareholders, and the broader community it touches, with the goal of explicitly doing good by all of them. Where CSR is often realized through a secondary or even vanity program tacked onto a company’s main business, Corporate Social Justice requires deep integration with every aspect of the way a company functions.”

UN GLOBAL COMPACT

In his essay, “Silent Reform through the Global Compact,” Hale further wrote that at the center of these UN efforts is the United Nations Global Compact.

According to Hale, the Global Compact is the “largest voluntary corporate citizenship initiative in the world, whose mission is to ensure that business—in partnership with other societal actors, including Governments, organized labor, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and academia—plays an essential role in achieving the United Nations vision of a more sustainable and equitable global economy.”

Its participants, elaborated Hale, “voluntarily commit to advance the 10 universal principles on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection and anti-corruption, which are derived from core UN treaties. And to give concrete meaning to this change approach, companies are expected to internalize these principles within their day-to-day operations and undertake projects to advance broader societal goals.”

Formally launched in 2000, the Global Compact counts over 3,000 businesses from some 100 countries as participants. With a combined employment of more than 10 million workers, these business participants are joined by over 800 civil society organizations, labor groups, city governments, foundations and academic partners. Country networks, which provide an arena for participants to engage at the ground level, have surfaced in over 50 countries.

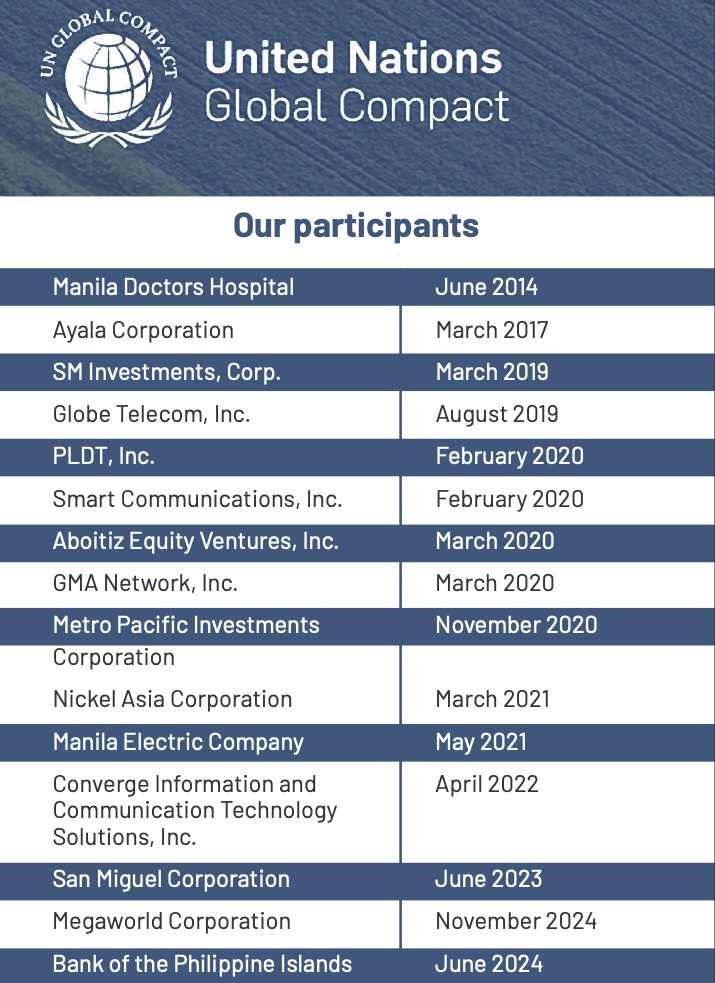

Currently listed in the UN Global Compact website, are 61 Philippine corporations, business associations, and NGOs participating in the initiative.

The website includes the date when the corporations signed the Global Compact. Included in the 61 top corporations listed are: Manila Doctors Hospital (June 2014), Ayala Corporation (March 2017), SM Investments, Corp. (March 2019), Globe Telecom, Inc. (Aug. 2019), PLDT, Inc. (Feb. 2020), Smart Communications, Inc. (February 2020), Aboitiz Equity Ventures, Inc. (March 2020), GMA Network, Inc. (March 2020), Metro Pacific Investments Corporation (November 2020), Nickel Asia Corporation (March 2021), Manila Electric Company (May 2021), Converge Information and Communication Technology Solutions, Inc. (April 2022), San Miguel Corporation (June 2023), Megaworld Corporation (Nov 2024), Bank of the Philippine Islands (June 2024).

________________

The future of social justice

Like in 2009, the humanitarian segment of the world today is bracing for its own global crisis.

When the United States voted Donald Trump as its 47th President, the world saw the most powerful nation in the world spawn an avalanche of wide-reaching policy changes that many believe will extensively affect marginalized sectors and the poorest nations across the globe.

On the day of Trump’s inauguration, the second-time US President signed an Executive Order that enforced “a 90-day pause in United States foreign development assistance for assessment of programmatic efficiencies and consistency with United States foreign policy.”

By February, the Trump Administration fast-tracked its dismantling of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and pulled thousands of the agency’s staffers off the job in the United States and around the world.

EFFECTS OF AIDS FREEZE

Early impact on the US aid freeze, as reported by the Associated Press, included: HIV-positive orphans in Kenya at risk as medical supplies dwindled; livelihoods upended for nonprofit workers, farmers, and other Americans; forced closure of health clinics in a vulnerable region of Syria; stalling of the work of NGOs that work to help millions of internally displaced people in Somalia; setting back the fight against human trafficking in Cambodia; and putting at risk Ukraine’s wartime help for frontline evacuees.

Through Executive Order 14155, signed by Trump on January 20, 2025, the United States stated that it is withdrawing from the World Health Organization (WHO). The U.S. is projected to contribute $958 million to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2025, which is about 15% of the agency’s budget. This makes the U.S. the WHO’s largest single donor.

As reported by the Associated Press, WHO is the UN’s specialized health agency and is mandated to coordinate the world’s response to global health threats, including outbreaks of mpox, Ebola and polio.

WHO also provides technical assistance to poorer countries, helps distribute scarce vaccines, supplies and treatments, and sets guidelines for hundreds of health conditions, including mental health and cancer.

In 2020, during the first time he became President, Trump tried to sever ties with the UN health body, officially notifying UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres that the US planned to pull out of WHO, suspending funding to the agency.

Former US President Joe Biden reversed Trump’s decision on his first day in office in January 2021. Trump essentially revived it on his first day back at the White House.

EFFECT OF US WITHDRAWAL FROM WHO

“A U.S. withdrawal from WHO would make the world far less healthy and safe,” said Lawrence Gostin, director of the WHO Collaborating Center on Global Health Law at Georgetown University. He said in an email that losing American resources would devastate WHO’s global surveillance and epidemic response efforts.

To withdraw from WHO, Trump will need the approval of Congress and a one-year notice to leave WHO. Some say this would not be an impossibility considering that both Houses of the US Congress is dominated by the Republican Party.

As the world turns, it seems that private corporations—both local and international—will have their hands full, if they pursue their role as enablers of social justice, through their various corporate social responsibility programs and projects. —with reports from Associated Press