by Gregorio Brillantes (August 1993)

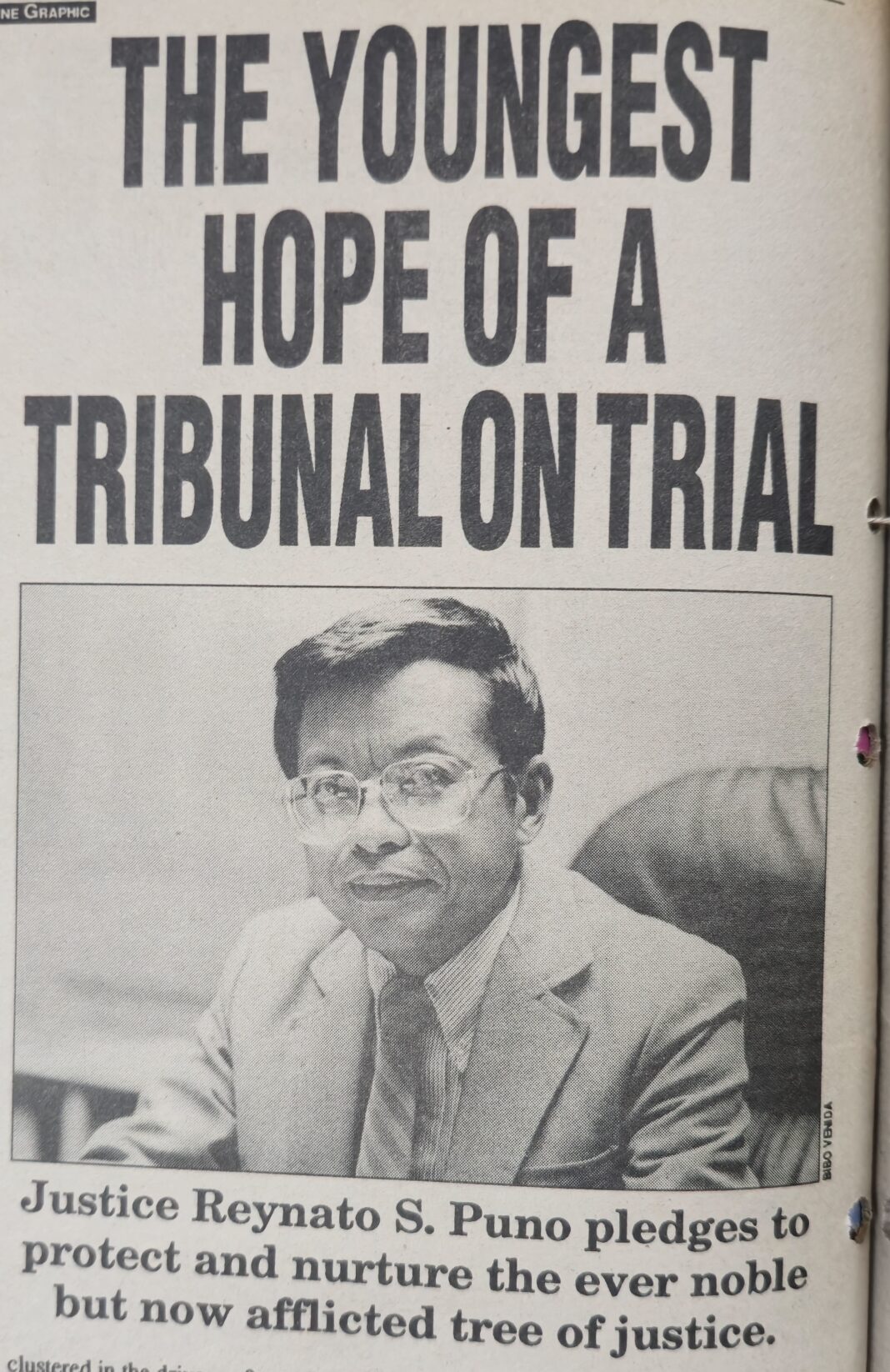

Justice Reynato S. Puno pledges to protect and nurture the ever noble but now afflicted tree of justice.

It looks like it’s going to be a long haul when you scan the country, or even just this part of town, from the corner of Taft and Padre Faura—a long dazed journey, not to “Philippines 2000,” the splendiferous miracle promised FVR’s faithful a mere seven years from now, but to reality of NIChood probably a century hence.

A wet afternoon the color of jeepney exhaust sets the tone for the dismal scene here on this block in Ermita that is one of the more entrancing sites around Metro Manila and which contains some of the most strategic and influential offices of the Republic. A mud-streaked sidewalk only less than a meter wide, it seems—“only in the Philippines,” as they say—is crammed with damp commuters, ID photo stands and assorted vendors along the old Supreme Court side of Taft, from the congested NBI compound to the dilapidated corner of Padre Faura. The jeepneys are doing what these wretched conveyances do best at street junctions, especially when the cops have gone off for coffee, which is create a traffic jam—in this instance, right below LRT line, which in the first place must have been designed to end such tormenting jams.

Plastered on the pillars of the LRT are signs protesting against the anti-people orders of the education and labor departments, put up no doubt by campus activists from the Manila Science High School and the Emilio Aguinaldo College across Taft and the UP’s Manila College around the corner towards the “new” Supreme Court building. More signs greet the pedestrian on Padre Faura: the street lighting project, which only late-night strollers might appreciate, was undertaken jointly by Mayor Alfredo Lim’s administration and the “new” Pagcor; litterbugs face a fine of P2,000 if not imprisonment. The warning is generally unheeded, to judge from so many Stork wrappers like green leaves strewn about, together with maruya and fishball stricks and other indigenous trash.

The Faura sidewalks are mercifully wider on either side, although one must still take care not to collide with the citizenry taking merienda or reading about small-town warlords and rapist-killers in the tabloids or just standing around, waiting for a dropped billfold or an economic breakthrough. On either side, too, are cars parked under the no-parking signs, including one rusty Toyota with two wheels positioned obliquely on the sidewalk farther up the street, between the Department of Justice and the UP Manila’s College of Dentistry.

Towards Maria Orosa and where Mr. Gokongwei’s domain begins, the noisy, impoverished, crowded shabbiness gives way to the elegance of the Faura Café and similar establishments. Through a coffee-shop’s misted window panes one glimpses strange circular ruins: the Ateneo chapel finally demolished despite the appeals and injunctions invoked reportedly by a Catholic women’s league from the Supreme Court and adjacent institutions.

Back in the ‘70s, the Ateneo sold its College of Law building beside the chapel to the owners of the Ramada Midtown and Robinson’s Department Store, and the huge statue of the canonized lawyer Sir Thomas More atop the chapel moved with the law school to Makati. “The King’s good servant, but God’s first” and the original “Man for All Seasons”—such was the lawyers’ patron saint, the great humanist and friend of the poor and martyr to the Faith, who defied the despotic will of Henry VIII and instead chose eternal loyalty to the Lord’s vicar on earth and as a result literally lost his head on the scaffold…

H. de la Costa Street in Salcedo Village, over which now broods the bronze figure of that most relevant 16th-century saint, is a long way, too, from Padre Faura—where More’s spirit, some would say, not just his sculptured Renaissance likeness, has been absent for some time now. This legal premise, a lawyerly proposition, you might say, brings us back to the object of this gray afternoon’s tour: the bulwark of our rights and liberties, the Supreme Court, which in this stormy month in the third quarter of 1993 is still under siege.

Visibly, publicly agitated as the visitor walks up the driveway of the High Tribunal is not some venerable jurist fuming over what Chief Justice Andres Narvasa calls the “polluted information environment,” but a woman driver trying with the grimness of the besieged to back out from among the cars parked three deep on the front court. Besides the population explosion, the nation or at least this busy official section of Manila must endure that of vehicles, unless the government decides, as once planned, to transfer all its principal agencies to the outer limits of Quezon City.

To such a move, however, the justices are not likely to say “aye,” en banc or individually, since the Supreme Court building, renovated in 1991 under the auspices of then President Aquino and Chief Justice Marcelo Fernan, is surely one of the few truly stately and magnificent structures to house Filipino officialdom. The facade like a Roman temple’s, with its white stone steps and classical columns, and within, the marbled corridors and walls, the tall paneled doors to the justices’ chambers—all this suggests a world different from the rest of government; something invincible, traditional and timeless, more so in contrast to the sad untidiness and near anarchy outside.

The visitor goes up broad stone steps aware that he is entering a world removed from the problems and perils that beset lower servants of the people. But a security guard keeps vigil behind one of the Greco-Roman pillars and he is holding a businesslike Uzi. Then one remembers there are a couple of sentries, soldiers in olive drab with slung M-16s, behind the wall by the shrunken sidewalk, on the Taft Avenue side.

Are the foes of the justice system—and there must be quite a few of these outside the law, outside the democratic fold in diverse ways—are they about to storm this citadel of the Constitution? Have those faceless poison-pen letter-writers a.k.a. “Concerned Practitioners” become so mad and desperate they might just take a sniper’s shot at a ponente on a promenade or lob a grenade at the No. 9 Benzes clustered in the driveway?

Nothing of course in the order of a Bong Revilla or Robin Padilla flick is expected to disturb the solemn tenor of their days. But the justices these days, or so one gathers from that “polluted environment,” are no longer as unperturbed in their remote niches as the people once perceived them to be, ages before the Supreme Court’s present critics began besmirching the august walls.

The highest court in the land continues to be criticized, attacked, assailed. This state of affairs is a measure of, among other things, how both governors and governed have changed since the tenures of Chief Justices like Cezar Bengzon, Marceliano Montemayor, Roberto Concepcion—times when not the faintest breath of scandal threatened the composure of the Court, and no concerned rumor-monger dared question its integrity. As the supreme arbiter and exemplar of justice, the Court is expected to aspire to a kind of secular sacredness. If it won’t or can’t, to what, to whom, as the cry goes, will the aggrieved and oppressed people turn?

The Philippine Daily Inquirer, clearly not Chief Justice Narvasa’s favorite paper, reports during the week the visitor goes to the Supreme Court, which is the third week of July: “Three new impeachment complaints were filed against Chief Justice Andres Narvasa and at least three other justices at the House of Representatives during Congress’s two-month recess…

“The complaints were filed by ordinary citizens who claimed that the SC justices violated the Constitution and committed other ‘impeachable’ acts in the handling of their cases…”

The first complainant, according to the Inquirer, claims that he was falsely charged by his employer with embezzlement during martial law and imprisoned unjustly. But the Fernan Court, including Narvasa as a respondent, rejected his petition for damages and other remedies on the grounds that it was filed in 1986, after the 10-year prescription period had lapsed. He was in prison during the Marcos regime, he said, and he could not file his petition then and expect the courts to be fair.

The second complainant, according to the Inquirer, alleges that the Supreme Court made a “sudden turnaround last year” in a P15-billion land case her war widows’ association was pursuing against a giant realty company. She earlier claimed that “a relative of a Supreme Court justice demanded P5 million from her to ‘settle’ the case in her favor…”

The third complainant “accused the SC of unduly delegating its power to decide on cases brought before it and pointed to a resolution signed by a mere clerk of court in the dismissal of a case he was pursuing in the SC.”

The three complaints—coming after all those rumors and allegations of misconduct and corruption which have kept Chief Justice Narvasa and other top judicious honchos in robes busier and perhaps angry above and beyond the call of jury—have been referred by Speaker Jose de Venecia to the House Committee on Justice chaired by Representative Pablo Garcia. “[But like] past impeachment complaints filed against members of the Court, the new cases,” the Inquirer noted, “lacked the necessary endorsement of at least one congressman,” and it was doubted whether “the complaints would be taken up by the 41-member [justice] committee…”

Also in Congress, the Inquirer tells us, the Committee on Economic Affairs headed by Representative Felicito Payumo has approved a resolution calling for the creation of a nine-man commission “to review possible ‘defects’ in the landmark decisions issued by the Supreme Court in the last 20 years.”

Meanwhile, and to no one’s real surprise, Atty. Miriam Defensor-Santiago jumped into the judicial ring and, as reported by the Manila Standard, “challenged President Ramos to name the persons behind an anonymous scandal sheet against Supreme Court justices, which she said is part of an effort to intimidate the justices and compel them to resign before they can reach a decision on her pending election protest.”

And then, striking close to home, there’s Associate Justice Teodoro Padilla’s proposal for a commission to investigate complaints against members of the High Tribunal. The recent Multi-Sectoral Citizens’ Forum endorsed Padilla’s proposal to create “an independent probe body composed of the two retired SC justices not engaged in the practice of law and the dean of a reputable law school.”

Justice Padilla explains his proposal in this wise: If the investigation of administrative complaints against SC justices is conducted by the Court itself, “skepticism abounds, for… the ideal of the cold neutrality of an impartial judge may be far from attainable. When a justice of the Supreme Court has to look into the conduct of a brother justice with whom he meets almost daily and break bread almost as often, the chances are the cards will be loaded in favor of the brother justice under fire…”

Chief Justice Narvasa has nixed Padilla’s plan, saying it smacks of “experimentation” and, besides, there already exist “built-in mechanisms under the Constitutions that vested the power to discipline the Supreme Court.”

In other words, ‘tis salutary to sustain the status quo, lest the Rock of Law, as another prestigious publication once called the Court, crack further and possibly crumble.

Mention of such travails as currently rack the Supreme Court brings a wan smile to the rather boyish face of the newly appointed and, at 53, the youngest member of the High Tribunal.

“The Court does have an image problem,” says soft-spoken Associate Justice Reynato S. Puno, who got his appointment papers only last June 28—one of the two newest members of the Court, the other being the equally accomplished scholar and educator, Dean Jose C. Vitug.

Observes Mr. Justice Puno as he sits in what looks like a brand-new leather chair behind a freshly varnished desk: “The judiciary as a whole is in a very peculiar position. It is very difficult for the judiciary to be defending itself against all these rumors and claims. For instance, on Chief Justice Narvasa’s trying to defend the judiciary, we have two schools of thought here. One would say that it is not proper for him to be doing so, the other school of thought would say that he is not doing enough. It is very difficult for the judiciary to be engaging always in this kind of argument, especially with non-legal persons.”

Would the Vice-President be one of these “non-legal persons”? Justice Puno would likewise agree, wouldn’t he, that things were much quieter in this temple of justice on Padre Faura before the Veep or one of his PACC agents or his ghostwriter added “hoodlums in robes” to the media’s vocabulary?

“We have no data on the rating of the Supreme Court before this so-called Erap exposé,” says the justice evenly, “so it is difficult to make a judgment, whether the Erap exposé has been responsible for the erosion of the image of the Supreme Court and the judiciary… But I tend to agree that a lot of these charges are disordered—disorderly…

“For instance,” the justice continues, “I came from the Court of Appeals, there are at least 50 justices there and each has written a thousand or more decisions. The statistics will show that about 98 percent of these decisions have been affirmed by the Supreme Court. Now, for one or two decisions some people disapprove of, out of the thousands that have been written, they demand that all justices and judges resign…

“Again, some people are demanding resignations, but the truth is, the solution is not mass resignations, that has been done before, for example after EDSA. Resigning is not the key to the problem. Related to this is the problem of reorganization, a very complex and delicate problem. First, you must have the goods on the corrupt judges and justices before you can kick them out, then you have to face the next problem, looking for better replacements.”

Be that as it may, it was one man’s resignation that can be said to have helped Justice Puno move up and away from the Court of Appeals on the Maria Orosa side of the block to where he now sits in his newly decorated quarters (paintings in the styles of Amorsolo and Magsaysay-Ho hang on the beige lamplit walls.) But no, he seems to smile with some relief, this office did not belong to former Justice Hugo Gutierrez. The latter resigned abruptly from the Court “out of delicadeza” after the publication of the Inquirer-Center for Investigative Journalism series claiming that it was not Gutierrez but the PLDT counsel who had written the decision favoring the PLDT over the British-affiliated Eastern Telecommunications Philippines Inc. (ETPI). The case in point involved the use of multi-billion peso “gateway” for overseas calls.

Justice Gutierrez’s retirement, which was not due until 1996, and that of Justice Jose Campos, who had turned 70, created the two vacancies in the 15-member Court which President Ramos filled only weeks ago. In a real sense Gutierrez’s replacement, Justice Puno has “inherited” the cases pending or on appeal in the resigned justice’s division. One of these is the PLDT case, which the ETPI lawyers have brought back for reconsideration. Which means Justice Puno will have a lot of work, even homework, to do in the next few weeks and months, not to say the next 17 years, before his own retirement from the Bench.

But he is unfazed, and cheerfully he describes himself as an “early bird”—and, the visitor readily sees, a diligent one. “Before eight I arrive here, and I work usually till six or seven, and take home cases for decision, including Saturdays. Compared with the Court of Appeals, here the volume is greater, the cases more serious. Here the most important cases are decided, on top of all that the Supreme Court takes care of the administration, the control and supervision, of the lower courts. All of which is quite a load.”

He tells of a typical working week: “Mondays and Wednesdays are devoted to division cases. We have three divisions, each with five justices. Tuesdays and Thursdays are devoted to en banc. And almost every day you have to tackle as many as 70 items on your agenda. Scores of judicial matters, cases filed either regionally or by appeal, coming from the lower courts, from various quasi-judicial agencies. Administrative matters such as complaints against judges, against employees of the lower courts like stenographers, clerks of court, sheriffs and others…”

He agrees that reforms should be a priority in the judicial system: “There is the common observation—the observation, too, of Vice-President Estrada—that we give too much due process to the accused. Our laws give litigants too many levels of appeal. Take, for instance, an ordinary ejectment order—this goes to the Municipal or City Court, then it is appealed to the Regional Court, then it is appealable to the Court of Appeals, then finally to the Supreme Court. All these steps and stages entail a lot of time, costs to the litigants and delayed justice.

“If you are a poor litigant, you get an unknown or ordinary lawyer who is pitted against a Makati-based practitioner. There, you see the difference between the legal combatants, that is why they say the rich and the poor can never be equal…

“In an underdeveloped country, there is always the problem of economics. An ordinary lawyer charges, I think, something like P1,000 per appearance in the lower courts. There are not enough free lawyers. There are not enough courts, or they are not available, even bond paper and certain papers, documents, are not available. Physical facilities are terrible.”

Given these burdens and pitifully scarce resources, the imperative, says Justice Puno, is “to prioritize our cases.” How to go about it? “Let us not, for example, treat a simple ejection case the way we should treat a case that involves millions of pesos…

“If you are a judge or justice trying a case involving millions of pesos and that case is not moving, you are tying up so much money that otherwise could go to economic development. That is what is happening. The 90-day trial—we aim for that, we are trying, but it is not easy. With respect to crimes, especially major crimes like kidnapping, rape, drug cases, my thinking is that these should undergo day to day trial. So that when the decision is handed down, whether conviction or acquittal, the public’s memory of the crime is still fresh, people will remember and learn…”

Another approach to “prioritization” is to revise some of the system’s technical rules and procedures. In this regard, Justice Puno has in mind “murder cases like the Lenny Villa case” involving those Ateneo frat boys: “The procedure is for the judge to issue a ruling. Then the ruling is immediately challenged and brought before the appellate court. How many rulings will a judge make in the course of a trial? Not all our judges are bright, and criminals can have very smart lawyers. So why don’t we change the rules and procedures as applied to these major crimes? Why not make it the rule that you cannot challenge every ruling?”

The setup, he concedes, has bedeviled the justice system from way back, and he thinks it’s exactly the sort of problem that should be addressed by proper legislation. “Otherwise, people will always be complaining about delays in the administration of justice. You cannot just blame the judges because that is the law. The law that the judges have to interpret.

“The problem, then, cannot be solved by the judiciary alone. It has to be remedied jointly with Congress and also with the executive. Because the fiscals, the prosecutors, are under the Department of Justice, the police under the Department of Local Governments. They are under the Office of the President, not the Supreme Court. It is a problem of the whole government and the public, not just of the judiciary.”

With such intense discernment and concern in the service of the highest, most decisive echelons of the judiciary, friends of the troubled Supreme Court may view with new hope and confidence its prospects both in the short term and on the advent of the Millenium.

The approach of August calls to mind the Assassination at the Airport. Yes, Justice Puno would agree with the popular verdict, that justice has not been meted out to “all those who were suspected of being involved in the murder of Ninoy Aquino.”

He would assume that Cory Aquino during the six years she was President “used all her powers to excavate more evidence.” Apparently the excavation work was as unrewarding as that Fort Santiago dig. “It could be very difficult job,” the efforts to ferret out all the conspiratorial biggies, and what many believe was more than one mastermind.

Reopening the assassination case, which is after all the most momentous murder of a famous Filipino in this century, is essentially an executive task. Further investigative work, the gathering of additional witnesses and testimonies—“these are within the purview of the Department of Justice, under the Office of the President.” He believes that if and when there are fresh leads, and even after the passage of years, “whoever is the incumbent President will not hesitate to reopen the case.”

The assassination of Filipinos by their own countrymen, it turns out, is far from an impersonal, abstract subject, as far as Justice Puno is concerned. He tells why: one high noon in April 1977, his eldest brother was shot dead from behind by an “NPA gunman” as he bowed his head in prayer before lunch, in a restaurant on the corner of Rizal Avenue and Lope de Vega. A .45 caliber slug blasted the skull of Manila CFI Judge Isaac Puno Jr. even as his infant daughter, dead from a congenital illness, lay on a bier in the Knox United Methodist Church across the Avenida.

“That was the saddest day for our family. On the day we were to bury my brother’s baby daughter was the time he was assassinated. Judge Isaac Puno Jr. was the chairman of an ecumenical church-military liaison group. “He was apolitical, he was trying to help iron out differences, conflicts, between the church groups and the military which was arresting and detaining church people as subversives. Doing that work, dealing with the military, he became a target of Communist elements. They killed him with one shot to the back of the head, NPA style. There were two others with the gunman—very young guys, 16, 17 years old. Later, the killers were apprehended and convicted.

“Then 1986 came, the EDSA Revolution. The new government and leadership decided on a policy of reconciliation, amnesty, and freed all those elements who were saying they were Communists. The killers of my brother—they were not in jail long enough, they were freed along with that batch led by Jose Ma. Sison. My sister-in-law and her three small children never got any help from the government. We felt we were the victims of those Communist elements, and the family was very unhappy to see the killers of my brother released, allowed to go scot-free.

“But what could we do? The government and leadership had made the decision that granting them amnesty was for the greater good of our people, our country.”

What the heart sometimes protests, the intellect and will must accept for thegreater good, if so decided by a legal, duly constituted government—a principle and conviction Justice Puno has made his own, at no little cost in blood and tears.

This quality of mind, the willed focusing of the intellect on what best serves the law and the land began to evolve, one gathers from Reynato Puno’s own retelling, on Alvarez Extension where he grew up, near San Lazaro Hospital and practically on the boundary between Santa Cruz and Tondo.

“I was born in Manila, in 1940, and I consider myself a Manileño. My late father, though, was from Pampanga, and my mother, a Serrano, is from Nueva Ecija. My father was a lawyer who was also in business, all sorts, like selling tools and eyeglasses. Yes, he was related, but distantly, very distant, to former Justice Secretary Ricardo Puno…”

The young Reynato was in Grade One at the Francisco Balagtas Elementary School, within walking distance from his childhood home, the year after the war, in 1946. It was another public school that he went to for his secondary course—the Arellano High School on Teodora Alonzo, which, “incidentally, was also the high school attended by Chief Justice Narvasa.” His “first love” as a high-schooler was journalism and accordingly was on the staff of the school paper, The Chronicler.

For his university studies, his father’s choice and his as well was the UP, first in the College of Liberal Arts for his two-year pre-law, where he met and shared classrooms with the likes of Heherson Alvarez, Ruben Ancheta, Haydee Yorac and Joma Sison. Then on the UP College of Law, under the deanship of Justice Vicente Abad Santos and later of then Judge Irene Cortez.

In second year law, he became editor of the Philippine Collegian. A frequent contributor was a very serious fellow, Jose Ma. Sison, he recalls with a wry smile. His associate editor was Leo Quisumbing, now deputy executive secretary in Malacañang. As a Collegian editor in that heyday of youth activism, he had his first close encounter with Congress, when he was summoned to appear before the House Committee on Anti-Filipino Activities looking into “Communist infiltration” in the groves of Diliman. The radicals on campus envied him for being the only undergraduate called to the inquiry in the company of Cesar Majul, O. D. Corpuz, Ricardo Pascual and several other UP officials and professors.

UP Law’s Class of ‘62 failed to produce a bar topnotcher, but he did hurdle the legal obstacle course with highly rated ease. He practiced for a while around Manila, before joining the law firm of then Congressman Gerry Roxas and future Justice Abraham Sarmiento as an assistant attorney. After that stint, he spent most of the ‘60s earning a number of master’s and doctoral degrees, all on scholarship grants, from such institutions as the Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas; the University of California in Berkeley; the University of Illinois—along with prizes for the excellence of his treatises on Comparative Private International Law, Constitutional Structure and other such subjects. (His style, one is told, shows the influence of the great jurists he admires: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Benjamin Cardozo, J.B.L. Reyes, Roberto Concepcion.)

Back on native soil in 1970, he began his career service in the judiciary as Solicitor in the Office of the Solicitor General. He has since served in numerous judicial positions, all leading progressively upward: Quezon City Judge, Assistant Solicitor General, Appellate Justice of the Intermediate Appellate Court, Deputy Minister of Justice and acting chairman of the Board of Pardons and Parole, and after the EDSA uprising, in August 1986, Associate Justice, Court of Appeals. That was where he was when President Ramos picked him, from the final list of 10 names submitted by the Judicial and Bar Council, as one of the two brightest and most worthy nominees for appointment to the Supreme Court.

Looking back, Justice Puno can tell himself he has arrived exactly at the destination he had desired from the start: “What I really wanted, when I went abroad for post-graduate work, and when I came back, was a career in the judiciary. I could have joined any one of the big law offices, no questions asked. If all I wanted was money, wealth, all I had to do was knock at the doors of the big law offices. I joined government when I came back from the US and have stayed ever since. After 26 years in the government service, the last 13 in the Court of Appeals, I was appointed here. Every career justice or judge strives to be here, in the Supreme Court.”

Now in the rare and infrequent hours when he is not pondering weighty matters of the law, Justice Puno devotes himself to three long-standing pursuits: chess, of which he is reputedly one of the judiciary’s more brilliant players; tennis, which he plays usually at the San Lucia Realty gum near his home in Fairview, Quezon City; and preaching at Methodist services. As a lay preacher, he expounds on the Gospel occasionally at the Knox United Methodist Church on Rizal Avenue and more often at the Isaac Puno Memorial Methodist Church in Fairview, founded by the Punos as a memorial to their slain brother.

They are indeed a devout, people-oriented clan, the Punos, whose Isaac Puno Memorial Foundation, assisted by evangelical churches in Germany, subsidizes the education of 130 high school and college students in Metro Manila. The second eldest, Levin, is the legal counsel of the United Methodist Church. Another brother, Carlito, is president of the Philippine Christian University. Paul, a Ph.D. who used to run the memorial foundation, now works as secretary for his brother the jurist. Myrna Puno-Pelayo is the director of Mary Johnston Hospital in Tondo, Isaac III is the director of NEDA and the youngest, Marilyn Puno-Santiago, is confidential assistant to Associate Justice Isagani A. Cruz.

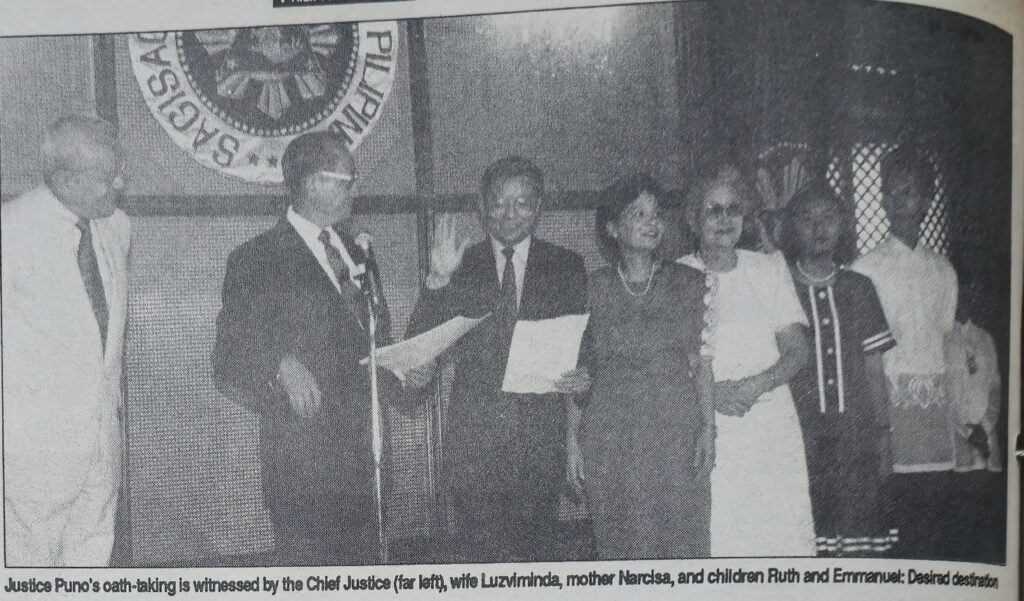

The justice’s own young family beams from a framed portrait on the wall, above a Bible open on a stand. The eldest of his three children, Reynato Jr., is 23 and finishing law at San Beda. Emmanuel, 19, is taking up business management at De La Salle. Marilyn, 12, is in Grade Six in Miriam College. His wife, the former Luzviminda Delgado, is Assistant Clerk of Court in the Supreme Court. When schedules permit, she joins him for lunch in his chambers, usually fish like pesang dalag and kandule.

Reflecting, finally, on what he considers his chief concern in the Court, he says it is “to keep the system of justice in our country strong, vigorous—and immaculate. The appearance of it should be presentable, admirable, to the people. You may be fair, you may be just, but fit the people think otherwise, the kind of justice you dispense may not be credible and effective justice…

“If I have come to this Court with that kind of idealism, I suppose it is because I come from the poor sector of our society. From the grades to the university, I studied in the public schools. My orientation is toward the poor and I think I am of liberal persuasion. So I specialized in labor and constitutional law. About 98 percent of labor cases wind up here in the Supreme Court. These cases concern the working class, the poor. That is why I am glad to be here.”

The visitor is gladdened, too, by this enlightening talk with the justice who is, in more senses than one, the youngest hope of the tribunal still besieged, who as his guest takes his leave rises to shake hands—lean, small of frame, but with the wiriness of the tennis player that he is, and the chess adept’s meditative gaze, and the humble yet confident voice and manner of the lay preacher who celebrates the promises of Christ.

The jurist in the City of Man is also a citizen of the City of God.

It is early evening outside on Padre Faura. The lamp-posts of Mayor Lim and the “new” Pagcor are alight, and a fine rain falls on the almost deserted street in the vicinity of which, in another age, the visitor sat in a shell-scarred classroom, and attended Marian devotions in the circular chapel dedicated to the sainted lawyer Thomas More, and listened to the Jesuits discoursing on the Law and the Scriptures, as Reynato S. Puno does on occasion in another chapel commemorating a beloved brother.

The visitor drives away through the light, illuminated rain which, by some nostalgic alchemy, brings back a story first heard in those distant days on Padre Faura.

Somebody, maybe a stranger newly arrived in town, was trying to call Loyola Heights for one reason or another, and by mistake dialed the number of another campus listed in the same section in the directory.

“Hello? Is this Loyola Heights?”

“No, this is Padre Faura.”

“Oh, Father. Good evening, Father Faura.”

Sorry, Ateneo joke only. But maybe worth one laugh on the rainy, rut-infested road to NICdom or just Buendia and Pasong Tamo. — G

Written by Gregorio C. Brillantes, this feature first appeared in Philippine Graphic, Vol. 4, No. 9, on August 13, 1993.