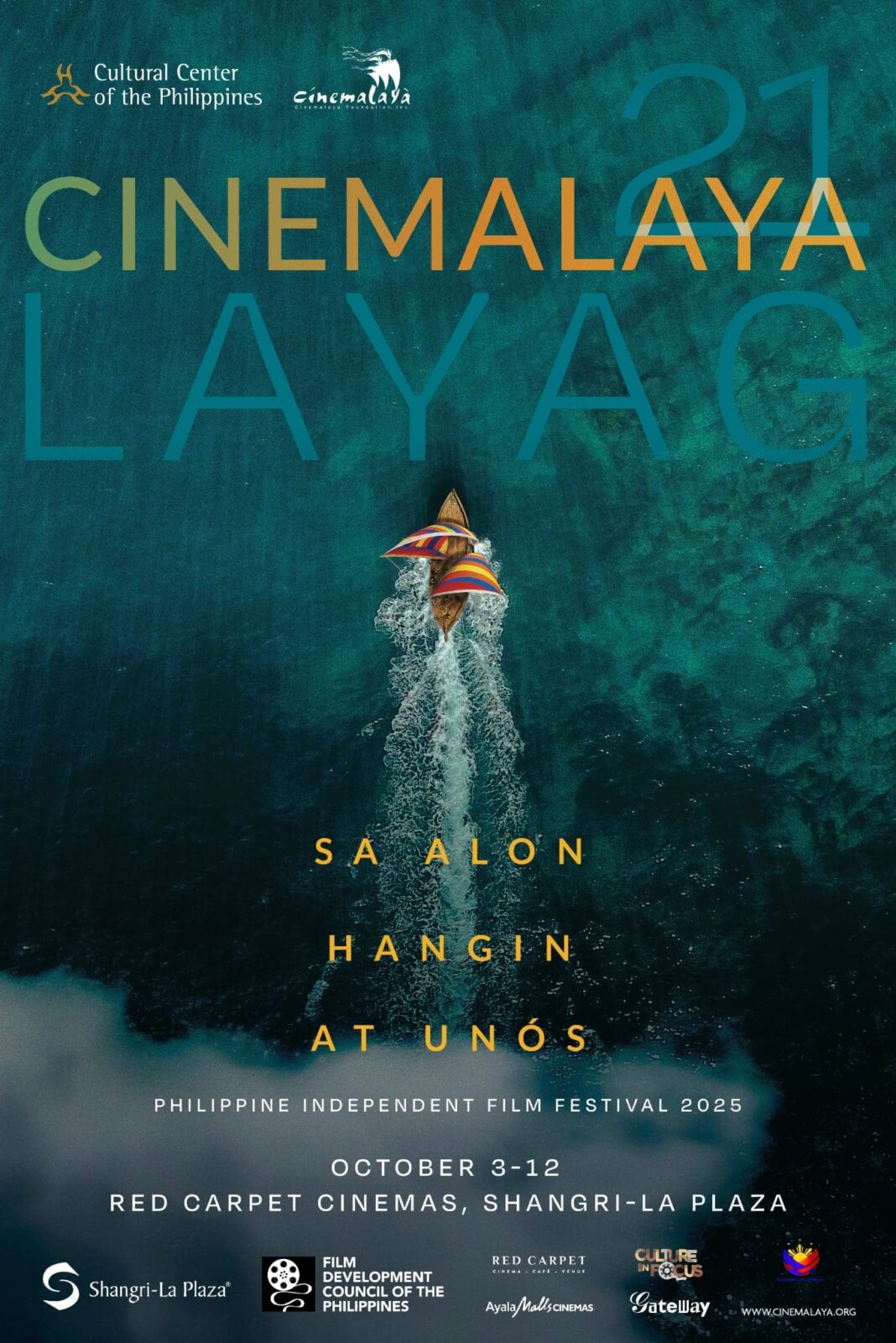

Since 2005, the Cinemalaya Philippine Independent Film Festival has served as a home for bold and heartwarming narratives. Among the finalists in this edition are regional films, often presented in local languages and rich with cultural authenticity. Their inclusion reflects the growing appreciation for diverse, grassroots storytelling in contemporary cinema.

This year’s featured regional entries are short films Kung Tugnaw ang Kaidalman Sang Lawod by Seth Andrew Blanca, Hasang by Daniel de la Cruz, Figat by Handiong Kapuno, and Kay Basta Angkarabo Yay Bagay Ibat Ha Langit by Maria Estela Paiso. These titles are part of the 10 short films competing in this year’s lineup.

Fascinating folklore and grounding realities in Cinemalaya 21 Shorts

With his three years of experience at sea, Blanca wrote Kung Tugnaw based on rumors of real accounts. “Sa barko, may mga usapan about sexual abuse na kadalasan, hindi na naire-report or basta na lang pinapabayaan,” he explained.

Blanca then juxtaposed the victim’s feeling of isolation with wide shots derived from his hometown, Igbaras, Iloilo.

Broadcasting graduate De la Cruz also took inspiration from Iloilo — this time, in the quaint town of Guimbal. Inspired by the popular indigenous belief of the deceased taking the form of animals or insects, his film Hasang is about a boy witnessing his grandmother turn into a tilapia.

“It describes how connection transcends life and death. I also cast actors from the area [Guimbal] to create a more immersive and heartfelt portrayal of our daily life and culture,” said De la Cruz.

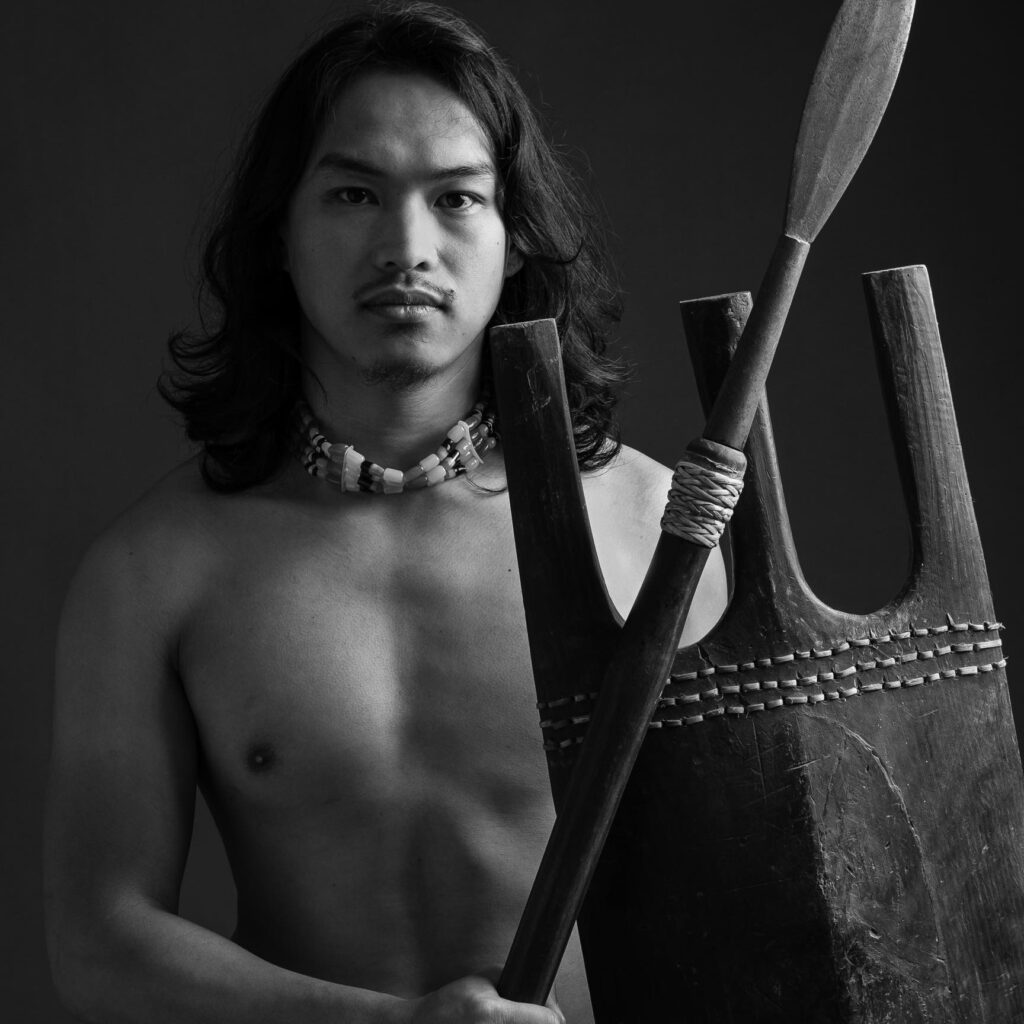

Through Figat, indigenous artist Kapuno honored his unyielding bond with his Kalinga roots. Because he spent his childhood hiking for two hours just to swim in rivers, he couldn’t help but observe, “Parang napaka-disconnected na ng mga bata ngayon.”

Kapuno conveys his worries through his protagonist Ching-ay, who crafts a traditional instrument of Kalinga.

In Zambales, Paiso shot Kay Basta with the West Philippine Sea conflict in mind. “Nalaman kong sinasadya ng Disney na lagyan ng nine-dash line ang mga mapa sa mga pelikula nila para mas bumenta sila sa China. Umigting din ‘yong Balikatan exercises,” she elaborated with frustration.

Backed by the voices of the fishermen community, Paiso’s short film centers on Sita, who swims in Zambales waters. The half-fish-half-human then listens to discussions of China’s territorial aggression.

Intertwining the absurd with sensible grief and anger

Paiso, who steered away from the mainstream, found it challenging to fund the animation sequences in Kay Basta.

Still, she stayed true to her film’s core: “Ang kuwento ng mga mangingisda ng Zambales ay hindi dapat kinakaawaan. Pinagmumulan dapat ito ng galit at panawagang tayo dapat ang nakikinabang sa likas na yaman ng Pilipinas, at hindi tayo pain ng sino man.”

In Kung Tugnaw, Blanca reflected on his own fragility and resilience. “Beyond the analog horror, gusto kong makaramdam din ang audience ng empathy para sa mga buhay na madalas invisible sa dagat, ‘yong seafarers,” he narrated.

Despite its absurd storytelling, De la Cruz explored grief through Hasang. His sincere wish is for moviegoers to contemplate its message: “I hope they feel connected to the small moments that remind us of what’s at stake in preserving our world. Our environment is changing and deteriorating.”

Kapuno also wrestled with the lack of resources in making Figat. “Literal siyang indie (hindi) madali,” he joked half-heartedly. Out of his determination to revive traditions that were fading in new generations, the film was born.

Kapuno continued, “Through Figat, I want people to see a life still intertwined with the music and stories of our land [Kalinga].”

Surreal representation in Cinemalaya 21 Layag: sa Alon, Hangin, at Unos

“P’wedeng-p’wede pala sumali sa Cinemalaya with an all-indigenous cast and crew,” Kapuno exclaimed. Driven by the weight of representing the Cordilleras, he urged aspiring and fellow artists to produce more meaningful films and cement the legacies of their ancestors.

For Blanca, having Kung Tugnaw included in Cinemalaya’s line-up is surreal. The experience also made him realize that being a regional filmmaker is not a limitation: “Gamitin ‘yong sariling dialect, kultura, at environment. That’s our strength.”

Meanwhile, Paiso’s success with Kay Basta reminded her of the rejections that led her to Cinemalaya. This marks her second entry into the film festival; her short film Ampangabagat Nin Talakba Ha Likol was a finalist at Cinemalaya in 2022. She recalled, “High school pa lang ako, mulat na ako sa eksena ng filmmaking dito sa bansa dahil sa Cinemalaya.”

Being a Cinemalaya finalist once felt like a distant dream for Hasang’s De la Cruz. But besides deep fulfillment, the achievement reassured him of his chosen path: “I truly believe that within our community lie countless stories that deserve to be told, so I’ll always choose Guimbal. I plan to come home after the festival.”

Cinemalaya has courageously showcased diverse narratives fueled by immense passion for over two decades. For regional filmmakers De la Cruz, Kapuno, Paiso, and Blanca, unveiling folklore and gripping truths in less than 20 minutes already warrants a celebration.

Even without the Balanghai trophy, they have already tasted triumph with the reaffirmation of their profound love for Philippine cinema.

Catch Paiso’s Kay Basta Angkarabo Yay Bagay Ibat Ha Langit, Kapuno’s Figat, Hasang by De la Cruz, and Blanca’s Kung Tugnaw Ang Kaidalman Sang Lawod from October 3 to October 12, 2025, at the Shangri-La Plaza, Ayala Malls Cinemas, and Gateway Cineplex 18.

For more updates, check on the CCP website (www.culturalcenter.gov.ph) and the Cinemalaya website (www.cinemalaya.org). Follow the official pages of CCP and Cinemalaya on X, Instagram, and TikTok for the latest updates.