Seven artists led the female-charged 37th edition of the Of Art and Wine exhibit in the form of loom and weaving

If one would lightly trace the original thread of weaving in our country’s history to find at what age we first practiced it, some poor-learned folk might think that 16th-century Spaniards brought it to the Philippines. However, our country’s relationship with textile and textile-making goes way back to the 13th-century, with indigenous Filipinos mastering the art of paghahabi and passing it down through generations.

Hundreds of years later, the art of weaving finds itself expressed in forms outside its own. In the 37th edition of the acclaimed Of Art and Wine (OAAW) exhibitions comes the theme of weaving in the form of the exhibit, Her Hands: A Loom of Stories.

Seven female artists—Kristine de Jesus, Anita del Rosario, Jane Ebarle, Mia Go, Katrina Raimann, Anina Rubio, and Maria Salvador—stood in the spotlight and showcased their art, which encompassed painting, sculpture, mixed media, and, of course, textiles.

Cooperation between Conrad Manila and Space Alt Contemporary made this iteration of OAAW exhibit possible. In a booklet they provided at the exhibit, they wished to “celebrate the artistry of weaving, not only as a craft, but also as a vessel of memory, identity, and connection.”

They continued: “By recognizing the artistry of weaving and the pivotal role women play in this tradition, we can appreciate the deeper narratives that each piece of fabric tells, celebrating both the skill involved and the cultural legacies that endure through time. Her Hands: A Loom of Stories showcases the contemporary works of seven women artists, each exploring their themes and narratives through textile art, sculpture, or mixed media.”

Lit up by small white lights and lined up along the long, light brown wall of the hallway, the art pieces ended up being drowned quite easily amid the crowd of wine-sipping spectators.

However, if one would deafen the ears—which I did with a healthy amount of focus, a noise-cancelling earbud on one ear, and a small dose of hesitance to participate in social conversations—one would end up finding some of the art pieces hitting the mark on being a “vessel of memory, identity, and connection.”

I said some, as not all of the pieces, unfortunately, were equal in their power. By that, I do not mean in terms of beauty. All the pieces, should it interest the inner world of the spectator, could be considered visually pleasing.

What I meant by power is in its power to celebrate the seven centuries of Filipino culture. In that regard, some pieces struck victoriously, while others felt foreign and wandering aimlessly.

Kristine de Jesus’s art exemplified this foreignness. Also known as Kutz, she is an artist who first found the courage to venture into the art world during the pandemic after two decades of corporate career. Debuting at Art Anton’s Fractals group show in January 2024, she had since then participated in other art events such as The Manila Bang Show and the Xavier Art Fest.

Five of her pieces were featured in the OAAW exhibit. All five—Sonoria, Driftalune, Moondrift, Celestia, and Nebuline—were made with acrylic and ink on canvas. In between the dizzying yet oddly satisfying lines that seemed to leave its echoes, and the bright and beautiful swash of colors, I found little trace and effect of the indigenous culture that the rest of the exhibit proudly cheered.

The artworks carry a peaceful beauty of their own—one that does not speak to me but might perhaps converse with someone else. If I were to put an image to its effect, I imagine that of a high noon summertime at a beach with strong waves, just at the mercy of an impending storm.

Nonetheless, it does not conjure in me an image of our enlightened forebearers speaking to their gods about their art.

When it comes to reviewing, it is of the utmost importance to see if the end product aligns with the promise, which, in this exhibit, would be the promise of cultural celebration.

Jane Ebarle’s execution aligns a little bit more. Like de Jesus’ artworks (but with the exception of ink), six of her pieces also made use of acrylic and canvas.

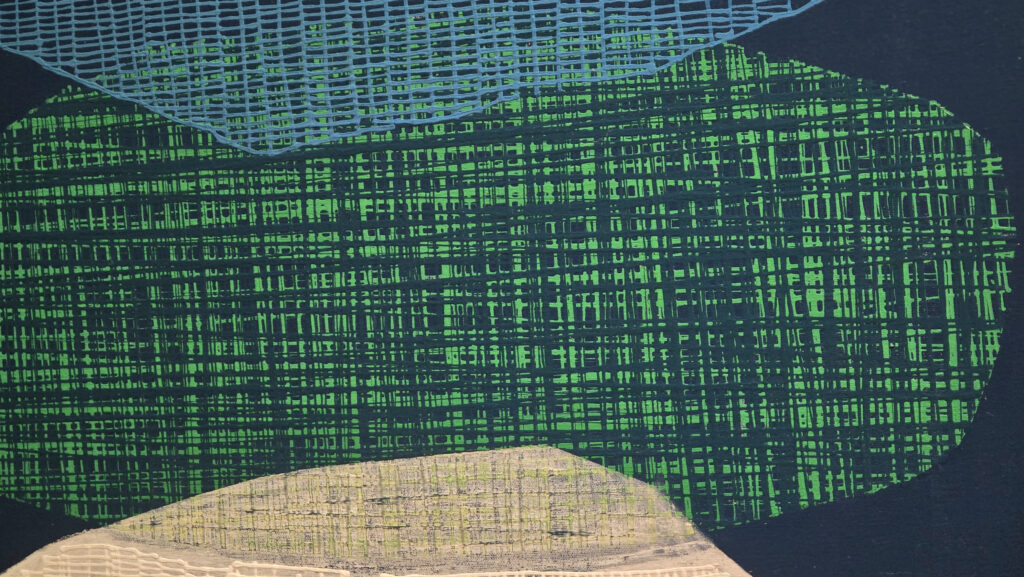

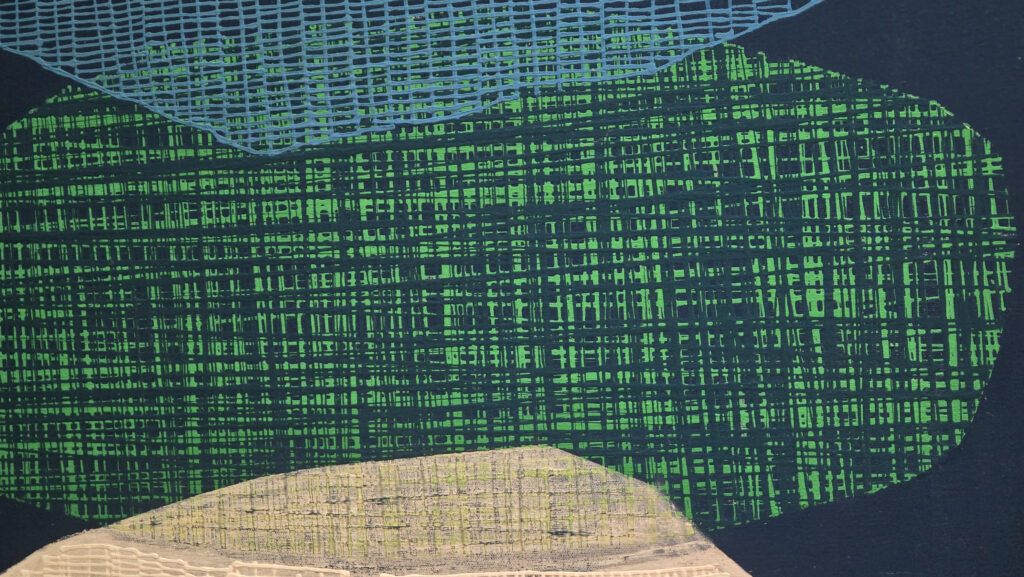

Ebarle’s famed Hibla abstract style, which mimics real fabrics, fits well with the exhibit. Four of her six pieces—Isang Yardang Hibla 16 CH, Isang Yardang Hibla 19 CH, Dalawang Talampakan ng Hibla 11, and Dalawang Talampakan ng Hibla 12—are what I deemed a “scientist’s approach” to the idea of weaving.

These four deliver a feeling of looking down at a swatch, distilling the craft to its barebones form. Her strokes and Hibla style provide the right amount of three-dimensionality to what would otherwise seem like impressionistic approximation of a fabric.

The greater focus is on two things. First, the minute detail of how each strand would interweave to form a pattern, as if looking at a city grid from above. The second is in texture, which jumps at you from the canvas and tempts you to touch it.

Her two other works—Kawes 30 CH and Kawes 31 CH—seems to be an expansion of her study in the previous four works, as she zooms out to a complete dress, with Kawes 31 CH looking like an intricate lacework, and Kawes 30 CH employing the use of a real fabric to extend beyond the two dimensions of a canvas.

Mia Go, Katrina Raimann, Anina Rubio, and Maria Salvador took a more direct approach in celebrating the art of weaving by actually weaving. They used different ways to do it. Mia Go used handwoven cotton wool and acrylic yarn in her works, Internal Landscape and Subliminal, the latter of which she suspended on a wooden dowel. She also wove cotton and wool or jute and raffia for her works, Roots and Memory, which seem to draw inspiration from indigenous traditions.

Katrina Raimann “painted” a scene by weaving burlap, cotton, wool, and acrylic yarn. The end result is four of her works which she showcased in the exhibit—White Cliffs, Sail Away with Me, Trimbach, and Bakod Nag Villa. In her works, I noticed a mixture of child-like innocence and an adult’s yearning for peace, of which the materials she used helped considerably in delivering.

Anina Rubio encased her woven textile art inside a bamboo frame. In fact, she had nine of them encased—all of which seem to be attempts at bringing recognizable order out of chaos. These, I felt, were more of an expression of her admiration of textiles than about weaving, particularly the varied ways in which one could view a certain material. My appreciation of it lies more in the technicality and the manner in which she executed it than in the end product.

The same could be said for Maria Salvador’s works which used fabric and fiber on textile, particularly five out of her six artworks—Where the Light Fades (48), Traces That Refuse to Fade, What Lingers After Words, The Fragile Side of Strength, and Where Silence waits Too Long.

Her work, too, seemed to me, at least, more of an ode to textiles than the art of weaving. That is not to say that her weaving is lackluster; far from it, actually. What I see from Salvador’s and Rubio’s works is the love for textile and how weaving simply is a means toward the expression of that end.

Salvador’s Void of Verdant Realm (42) felt more of a rebellion from what her five other works had accomplished, leaving a symbolic void that does not exist in others. The void becomes a break from what weaving seems to be usually interpreted—a tight-knit plane of threads woven together with no empty space spared. Which is quite erroneous, considering that clothes have plenty of holes for it to be worn, and holes exist at the ends of certain textiles as a way for it to be hung. Void of Verdant Realm (42) doubles down on that.

We have journeyed from various roads through which one could celebrate “the artistry of weaving and the pivotal role women play in this tradition,” and seen ways in which an artist interprets or reinterprets the art form. Some were direct manifestations; others took more abstract routes.

But what do we leave for Anita Del Rosario? One could argue that her works at the exhibit were as foreign to weaving as de Jesus’s paintings. And on some accounts, that is not entirely wrong. Being an accomplished in jewelry design and sculpture, her pieces—Milagros (With Fish), Milagros (With Basket), Inang (Mini), Nude Woman, and Lucky—made use of nacre (or Mother of Pearl), paua, brass, copper, and wood. None seems to be related to weaving. It neither celebrates textile nor the ingenious art of commanding it.

If the aim is to champion “the artistry of weaving and the pivotal role women play in this tradition,” is Anita Del Rosario too far off, then?

No—because those weren’t the things that her art celebrated. It was the women she celebrated.

Out of all the pieces that were there, it was her four sculptures commemorating women that struck me as the most powerful. The way in which she commanded nacre and brass to the form of a woman was a showstopper. She had, I believe, given life to the inanimate. As I stood there in awe of her sculptures, it struck me how she made it seem as if nacre had always been the best material to show a woman’s strength.

All the works of the seven artists are up for auction. I am of the belief that there is always an art for somebody, which would strike a chord in their soul as deftly as a couple of the works briefly did on mine.

Of Art and Wine’s Her Hands: A Loom of Stories exhibit will be on display from September 16 to November 15, 2025, in Gallery C at the third level of Conrad Manila.