I watch my Mama pour a sachet of Milointo three cups, adding a lot of brown sugar to it—stirring them slowly, as though she could stretch the day out longer than it will last. Her shoulders droop, and a deep sigh escapes her pale, heart-shaped lips. She unwraps the puto cheese, placing a piece on each of our plates—one for me, one for my older brother, then carefully halves her own portion. She divides the other half again, placing a piece on both of our plates. She hands it to us with a warm, reassuring smile I know so well. She must have added the food on our table to the list of her debts from Manang Vilma’s store. I know she’s hungry, too, but she says she isn’t as she watches us eat the puto and drink the Milo. Later, when we’re asleep, I know she’ll turn away from us and cry in silence. I know, and so I smile back at her, finishing my meal. With each bite, I glance up at the medals neatly hanging on our wall, pretending to count how many are mine and how many are Kuya’s. With each gulp, I turn my face, avoiding her gaze. This dinner shall pass. Soon, my Papa will come home. Tomorrow, we’ll have chicken adobo and warm rice, with a bottle of Coca-Cola to wash it down.

The day isn’t over yet. Papa will come home. He will come home and buy my scores from the periodical exams. Twenty pesos for each perfect score. He will come home and scold my brother for sneaking out from our afternoon naps. He will come home and greet my mother with a happy birthday. He will, and we just have to wait a little longer.

After our simple dinner, I wash the dishes while my brother sweeps the floor, preparing the mat for us to sleep on. Mama gathers the clothes she has hung outside and folds them neatly. It is an ordinary day, but it is Mama’s birthday. Kuya unrolls the purple-striped banig and spreads a layer of cloth on top to make it comfortable. We can’t afford a proper bed, so Mama makes sure to cover my side of the banig with a thick layer of cloth, knowing how easily I catch a cold. The place we are staying is a rented room—previously a small sari-sari store. It is not even for rent in the first place but since the landlady is my Mama’s friend, she let us rent it. I switch off the lights and lie down between Kuya and Mama, but despite it being only 8 p.m., I can’t sleep. I wonder if it is my stomach growling or if I am just too anxious, hoping my Papa will knock on the door anytime soon. I look up at the nipa roof and find a tiny hole that shines through the dark. The silence feels heavy, yet strangely soothing. A few minutes later, I hear my Kuya grinding his teeth in his sleep. I can’t resist softly slapping his face to quiet him. He must be exhausted from selling ice at the market, carrying heavy sacks and delivering them to the fish and meat vendors. I reach out to hug Mama, but her skin is burning with fever.

“Ma,” I whisper, gently shaking her shoulders, hoping for a response. “My father must be visiting me because it’s my birthday. He probably wants to take me away,” she murmurs, a pained groan escaping her lips. “Don’t say that, Mama! I’ll buy you medicine,” I plead, my voice thick with worry. “It’s late, Tayan. Just go back to sleep. I won’t die tonight,” she replies, her words soft but firm. Fear always settles in my chest when it’s her birthday because she always falls ill. There’s something in her eyes—this distant birthday look that tells you she just wants to rest in the garden, forever. She always says her father is coming to visit, but my Lolo has been gone since Mama was just six years old.

I muni-muni as the cold wind hovers over our tiny home and when I snap to reality, I watch over my Mama and wait for my Papa. He must have a reason, but whatever it is, it’s been a month since he last came home. My eyes then drift to that tiny hole on the nipa roof where stars peek, as if they were telling me they have found my Papa, and he is alright. And we will be okay.

“He’s not coming back, anak. Just sleep now,” Mama says, breaking my thoughts. She turns toward me and gently taps my leg with her fingers, just like she always does when I can’t sleep as a child. And just like that, her touch soothes me, and I drift off, feeling for a moment like nothing really matters.

The sun kisses my skin as if it owns me—golden and warm, urging me to follow its path until it meets the sea. But sometimes, the stormy places feel more like home. A room without a doorknob feels safer. A plywood table with no chairs feels somehow complete. Anywhere with my Mama and Kuya is my home, even if it’s under a nipa roof that leaks when it rains. A roof that my brother repeatedly fixed by tapak-tapak because we can’t afford a steel roof. Now, a bowl of Lucky Menoodles, flooded with water, is the perfect breakfast.

Kuya has left early to join the kubkuban, a group of fishermen with large boats who set out at dawn to catch fish, crabs, and squids. In our barangay, it is usually a family business, and their surnames are painted on the boats. Today, Kuya went with the Vicera family. They will probably be back in an hour or so, with people waiting on the shore, hoping for a free share of the catch.

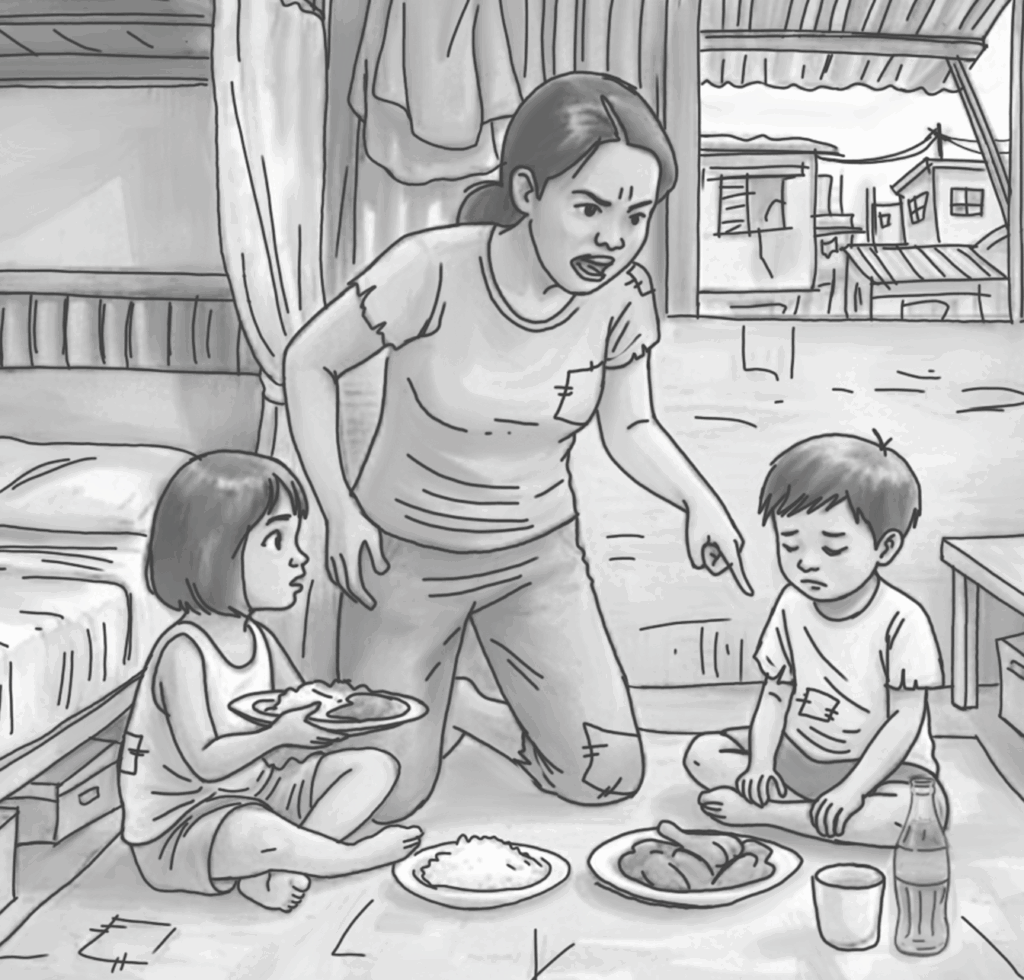

When Mama found out last week that Kuya had been going with the kubkuban, she was so angry she hit him with a hanger until it snapped. As she scolded him, I hid behind the door, listening carefully in case I needed to shield him and take the beating. But then Mama broke down in tears.

“Punyeta kang bata ka!” She yelled at my brother who’s kneeling in front of her, Mama’s neck veins bulging with rage. I didn’t know why, but there was something about that moment—a strange air that made my spine shiver that told me Mama was embarrassed. She was embarrassed that her son had to work at such a young age. She was embarrassed that people would think we had nothing to eat. I couldn’t bring myself to be angry at her.

Instead, my heart ached for her. She must have missed her life before she eloped with my Papa. She was a rich carefree college girl whose life was ahead of her. Not until she fell in love with my Papa. Now, she’s stuck in a depressed province, a single Mom with two kids, living in a house with no exit.

Mama always made sure we wore nice clothes and shoes. She’d style my hair with ribbons and clips, one for every day of the week. She did everything she could to make us look presentable. She would be furious if we didn’t take our hygiene seriously.

“You must look good, so no one bullies you. Look good, so people won’t think your parents are poor. That way, they won’t look down on you,” she’d always say.

I set aside the remaining noodles in a plastic colander for Kuya when he comes home. I will just reheat it, and it will be as delicious as when I had eaten it earlier. Mama has already eaten and is now tending to the plants in the little garden she has made just outside the room we rent.

I decided to join Mama and step out of the room. As I emerge, I see a man’s silhouette cast on the white cloth hanging from the rope tied to the talisay tree. She must have done Manang Berna’s laundry while we were asleep. Manang Berna is our landlady, and my Mama does their laundry to compensate for the rent we have not paid yet.

Beside the man’s silhouette is Mama. It’s her—the long curls that hang on her shoulder, the shape of her protruding forehead. I take a few steps toward them, and that’s when I see her punch the man on the chest. I quickly move the cloth aside, trying to understand what is happening.

Mama continues to throw herself at the man, sobbing as her weak punches land. I can’t make sense of it until I see the man’s face. Time seems to stop. I stand frozen, as if I am invisible.

With every ounce of strength she has left, she breaks free from the man’s attempt to embrace her. She grabs the tabo she uses to water the plants—and throws it at him. It hits his shoulder, but it seems like nothing more than a harmless tap, given his build. Next, she grabs the pail, where she had stored the water earlier, and throws it, too. But it doesn’t reach him, she lacks strength.

The man stands there, unshaken, almost as if he is prepared for whatever Mama might throw at him. His red, sleepy eyes watch her, and the sun makes his fair skin glow, casting a shadow over Mama as he towers over her.

Her knees buckle, and she collapses to the ground, her hands reaching for the sundang. I can’t read her face, there is no telling what she might do with it—but the look in her eyes terrifies me more than anything I have ever seen. My heart hammers in my chest, loud and frantic, reminding me that I exist now.

“Ma!” I croak, my voice hoarse. She doesn’t look at me, doesn’t seem to hear me, nor does the man standing in front of her. I want to rush to her, take the sundang away, but my feet are rooted to the ground. I can’t move. No more words come out of my mouth.

“Just let me take you to the hospital” the man finally spoke, his tone almost begging.

Mama’s face was flushed, tears streaming down like rivers, never stopping. She grips the sundang tightly, but doesn’t point it at anyone—just holds it, like her life depended on it.

I look at the man, his face softens but his posture remains firm.

“You don’t get to be the nice man here, Jose. Just leave. I have a garden to take care of” her voice is fragile, shaky, it sounds like a plea.

I stare into the man’s eyes as he lets out a laugh. Before I know it, tears stream down my face, racing down the chubby cheeks I inherited from him. My full lips, just like his, tremble, trying to hold back a sob. His laugh scares me. Because why would he laugh?

For the first time since I froze, he looks at me. His smile reaches his ear and turns to walk away. I watch him go, his back fading into the distance. I watch until my tears run dry, until my knees give out, and I fall to the ground just like Mama has.

My Papa came home only to leave us again. I wish he had never shown up that day, so that my last memory of him can be the picnic at Luneta Park during that vacation we had. I wish he has never shown up, so that I’d remember his smile when I stuffed my mouth with lumpia on New Year’s Eve. I wish he had never shown up, so I could still tell my teacher he was my hero when asked.

Rough hands lift me from the ground. I look up and see my Kuya’s face, flushed and sunburned from the heat. He gently wipes my tears with his fingers and tucks my hair behind my ear, his eyes searching for any signs of injury. He carefully brushes the dirt from my knees, his touch soft yet steady. Once he is sure I am okay, he turns to Mama, helping her to her feet before guiding her back into the house.

As if nothing has happened, my brother quietly pulls a freshly cut chicken wrapped in plastic, a kilo of rice, and a bottle of Coca-Cola from his sack and places them on the table. The silence between us hangs heavily. Before he closes the bag, his hands rummage deep inside, pulling out two pieces of paracetamol, which he hands to Mama. The sight of it only makes her cry harder. He does not say a word but instead caresses my mother’s back until she calms down.

“I’ll cook you chicken adobo, so stop crying now, Maya,” he says, flicking my forehead. He calls me Maya, like the bird, because he says I am small and noisy, especially when I cry. He starts teasing me, and for a moment, I can’t help but smile, grateful for the thought that we will have a proper lunch. Mama gets up and begins clearing the dirty kitchen, readying it for cooking.

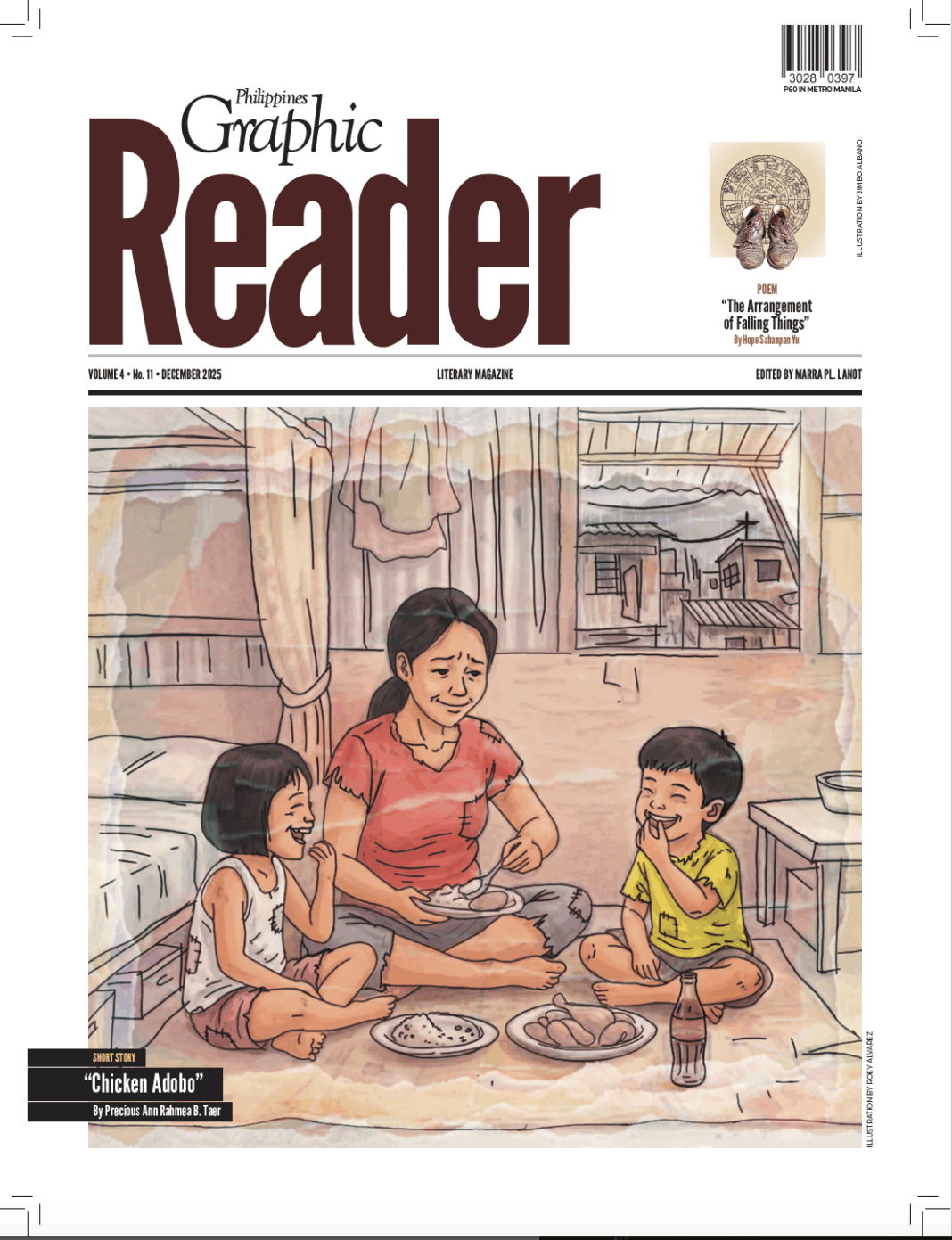

The rich aroma of chicken adobo fills our tiny house–savory and comforting, while warm rice piles high on our plates. The cold Coca-Cola sits in a glass, glistening, waiting to be welcomed into our stomachs.

Mama and Kuya watch me as I happily bite into the chicken drumstick. I pause, wondering why they are looking at me. Am I eating too fast? Am I chewing too loudly?

“Go on, eat more!” Kuya says, placing another drumstick on my plate. I can’t contain my happiness, and although I know drumsticks are also his favorite, I accept it without hesitation.

“You were praying in your sleep, asking for your Papa to come home so we could have adobo for lunch,” Mama finally says, her voice trembling, and I can tell she is on the verge of tears again. Did I really say that in my sleep? Guilt twists inside me, and without thinking, I place the other drumstick on her plate, hoping it will stop her tears.

Every day, the Marites gossip about our family, pulling me into their conversations. They tell me where my father is, urging me to visit him because they’ve heard he has lost his mind. They say that a man would naturally lose his mind if his partner and his children would abandon him. They blamed my Mama and called her ungrateful, even evil, despite her face being described as angelic—like Mama Mary. But they don’t know that my Papa is the one who abandoned us right when Mama was suffering from a stomach ulcer. My father knew, but he still left.

A few mothers give us a portion of food they have for the day. Sometimes enough for two stomachs, oftentimes my brother and I would settle for a burikat bread–sliced into twelve parts, sold for twelve pesos. We’d divide it among ourselves. Two tiny pieces for breakfast, two for lunch, and two for dinner. For the times we run out of money, we’d starve and hope that water would be enough. I still think of chicken adobo–how juicy and tender that drumstick is, and the aroma is so sweet. But I have never wished and prayed for it like I did before.

I promise myself not to eat chicken adobo until I deserve it. I hate myself for praying back then. Poor little girl praying for a chicken adobo, when her Mama was dying in pain. How foolish of me.

My brother worked tirelessly in the kubkuban. He was always out at sea, and his hands grew rough and blistered. To earn more, he took on extra tasks—running errands for the boat captain and the other men who worked alongside him. He became their errand boy. At just eleven years old, he became the pillar of our house after our father, a drug addict, left and never came back.

No matter how strong he tried to be, I see the moments when Kuya‘s guard slips. I see him bow his head when people stare and whisper about our family. He would gently cover my ears, forcing a smile in my direction—but I could see it clearly: his eyes shimmered with unshed tears, and his lips trembled, struggling not to give in. I understand what the neighbors are saying. But I don’t want to add to his burden. So I smile back at him, pretending I haven’t heard a thing.

We are bullied, even if we wear nice clothes. We are looked down on, even if we are clean.

Fifteen years have passed, and the Marites are still the same, gossiping in the streets, their hair now grey and wrinkles deepening on their faces. I sometimes wonder if they still talk about us, but honestly, I don’t care anymore.

I click the lock open and step through the gates. The bougainvillea–purple and pink, vibrant as ever—welcomes me like a long-lost family finally returning home. The grass brushes against my feet, its soft tickles a reminder of forgotten childhood play. It was a short walk until I reached my mother’s grave, each step, a quiet longing. Suddenly, a voice calls from behind as if it is always there. “How could you come here, without telling me?” I turned around startled and before I could say anything, he was quick to flick my forehead.

“Ouch! I’m not a kid anymore!”

“Yes, you are. You will always be my bunso.”

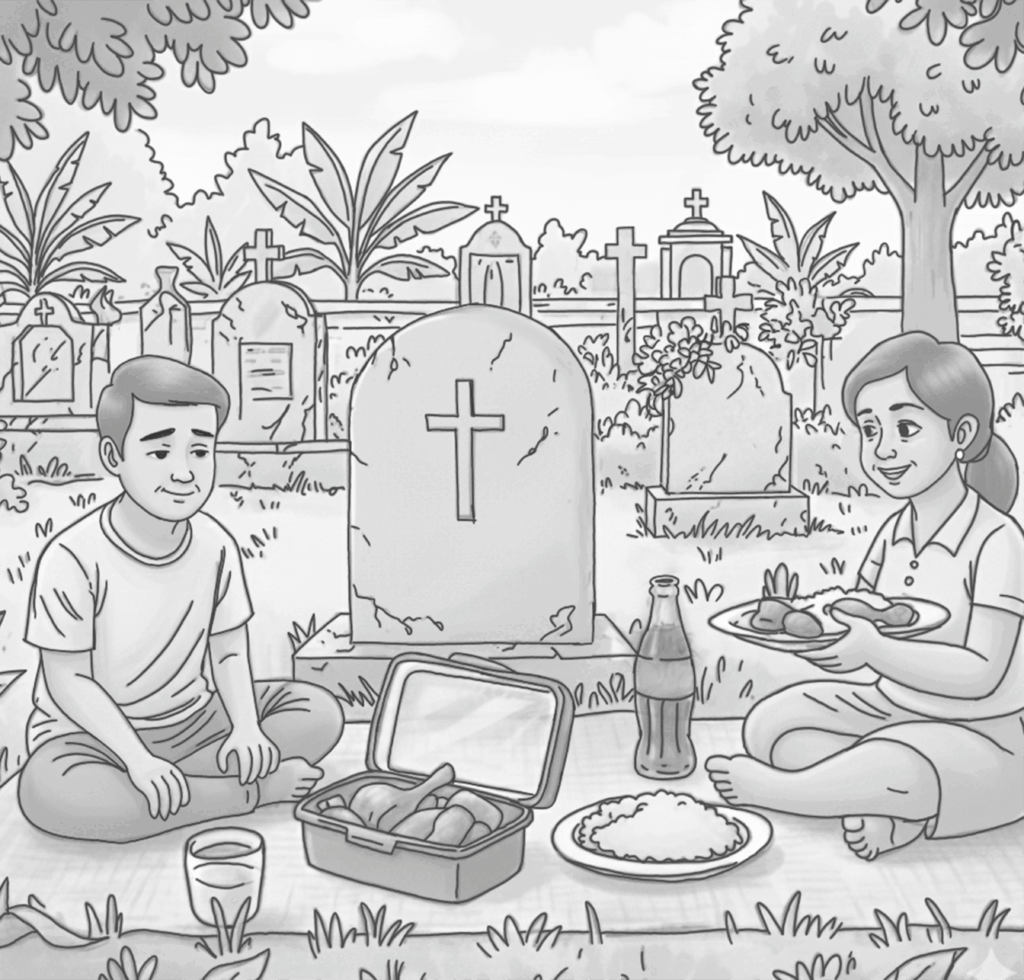

He unrolls a picnic blanket with practiced ease, then opens a lunchbox containing steaming chicken adobo and another filled with warm, fluffy rice. He pops the cap off a bottle of Coca-Cola with a familiar twist—the sound sharp, comforting. The way he moves, so fluid, so certain—tells me he’s been doing this ever since Mama became one of the gardens.

We sit down in silence, having quiet conversations only we can hear. Kuya places two drumsticks on my plate, just like the old times. I take a bite, stuff my mouth with rice, and try to swallow the lump in my throat. The tears come, anyway—slipping down my cheeks as I chew. It stings that I no longer need to pray to have adobo on the table. I can afford it now, but Mama is no longer here.

Kuya taps my shoulder—softly, the way Mama used to soothe me to sleep. He doesn’t say anything. Just that one tap, and I break even more. I wonder if anyone ever taps his shoulder, too.

The breeze brushes my cheek like it knows what today is. For a moment, I swear I hear it whisper, “Go on, eat more, Tayan.”

I smile, the drumstick warm and heavy in my hand, and take another bite—savoring the sweetness and tenderness of what it used to be. What we used to be. I kneel by her grave, tracing her name with my fingers, and whisper, “Happy birthday, Ma.”